The Definitives

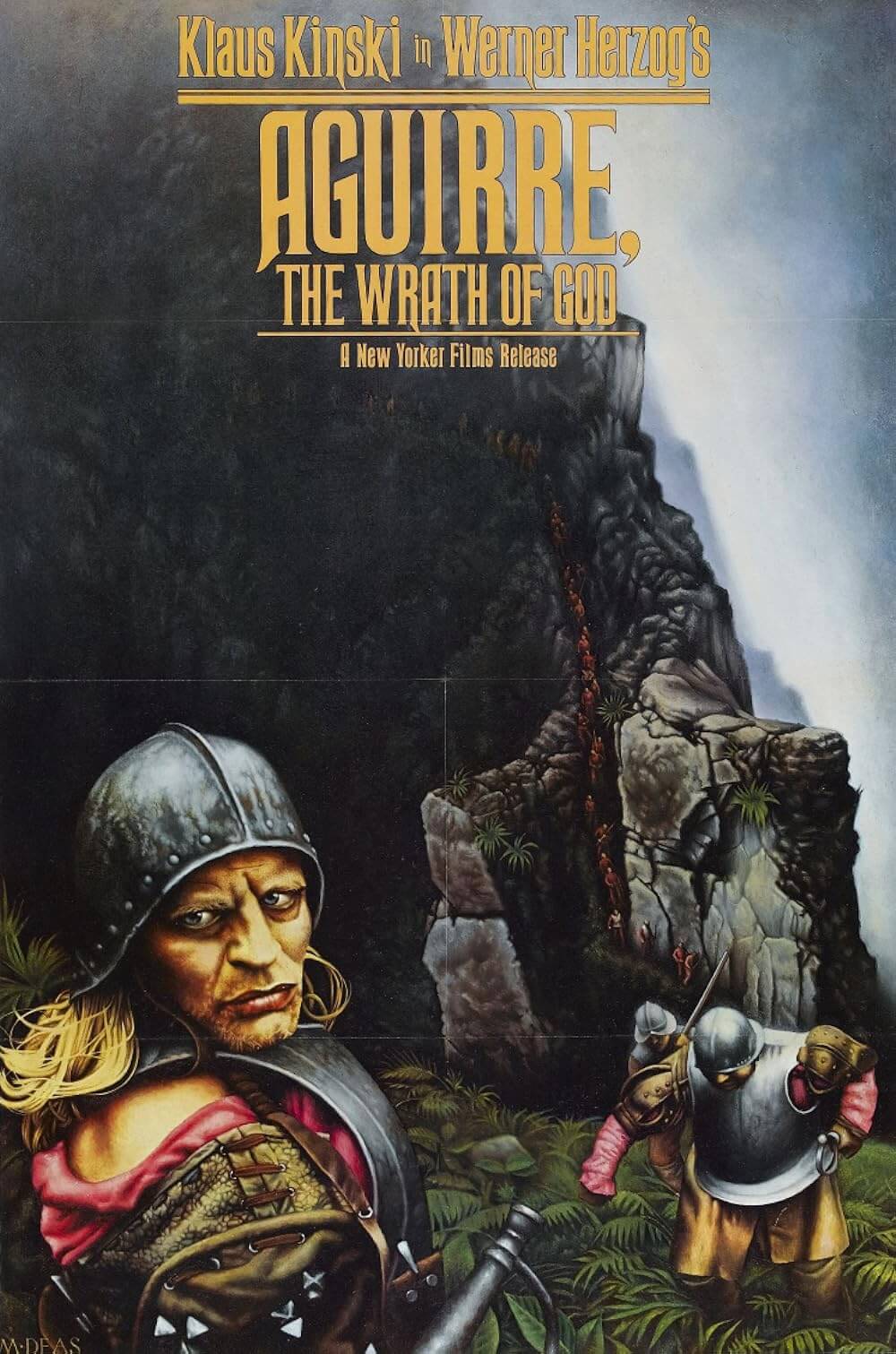

Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

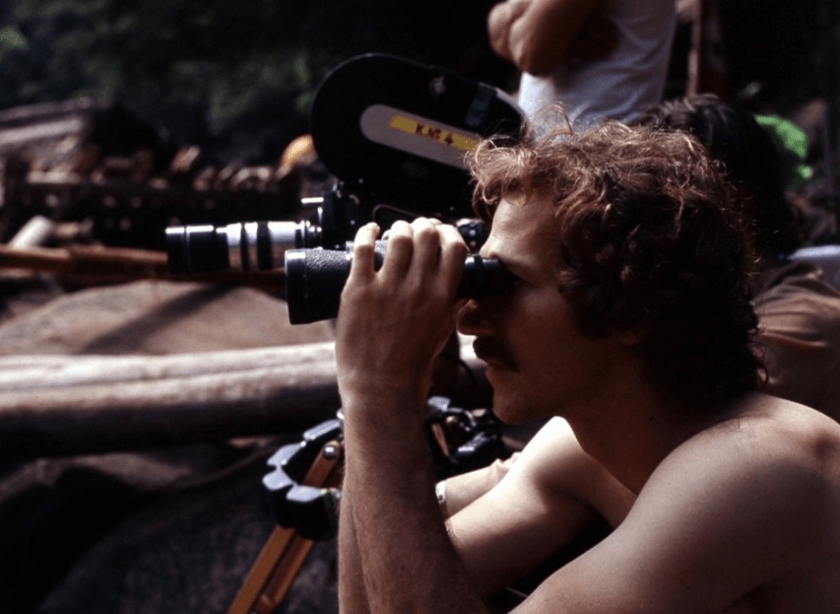

To achieve the opening shots of Aguirre, the Wrath of God, director Werner Herzog sought a location atop a mountain near Machu Picchu, in Peru. He led his cast and crew, some 450 people, along with a procession of horses, pigs, and llamas, up the side of the mountain. Together, his troupe slogged an ancient stairway that the Incans carved into the rocks centuries ago, passing through dense jungle on steep footing made slippery by pouring rain. Visibility was nil, as clouds enveloped the entire mountain, shrouding everything in thick, damp fog. At an altitude of 14,000 feet, even the local upland natives became sick with vertigo, while the actors braved these conditions wearing their heavy costume armor and Spanish conquistador dress. The journey seemed impossible. Herzog had to convince his people to keep going, to keep climbing higher and higher along a vertical drop of about 2,000 feet. When they finally reached their destination, Herzog worried that it was all for nothing. The haze was so thick that his camera could only see a couple of feet out. Then the clouds dissipated, and daylight broke through. Herzog got his shots, capturing a line of actors, mere specs within the frame, moving down the Incan stairway between a sharp mountain slope and a mass of fog. Herzog felt a miracle had occurred. He remarked on his good fortune, “It was on this day that I definitely came to know my destiny.” Ironically, it was that kind of wild determination and pretense of fate that drove his film’s fanatical protagonist, Lope de Aguirre, played by Klaus Kinski, to his own oblivion.

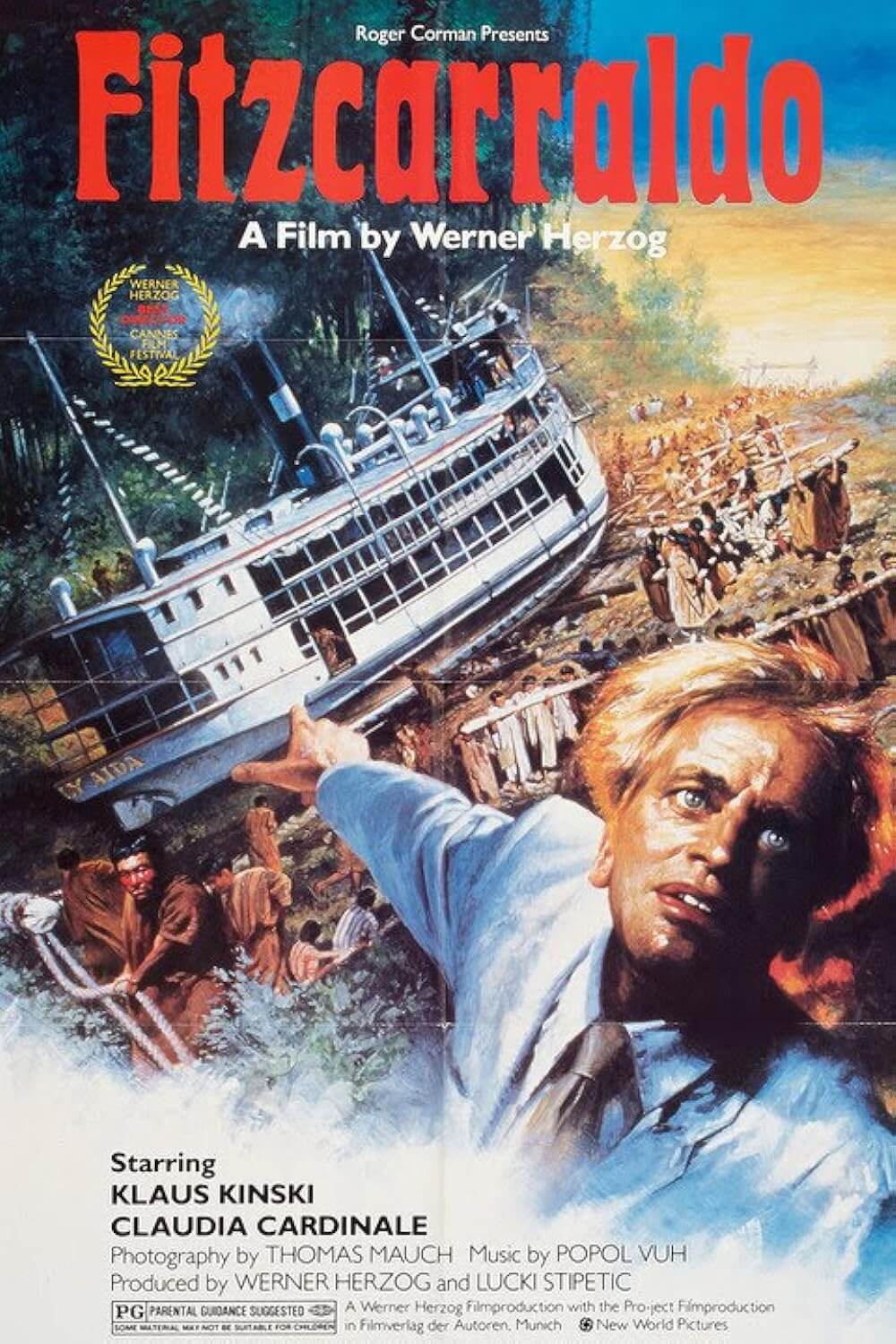

Before Herzog was known for making documentaries such as Grizzly Man (2005) or Encounters at the End of the World (2008), about people possessed by passions in distant, impossible locations, he made narrative films about that very subject, therein proving he shared their obsessions. Aguirre, the Wrath of God was his first such film, and it was also Herzog’s first international success outside of his West German homeland. His 1972 release charts a doomed Spanish expedition to locate El Dorado, the fabled Incan city of gold. On the surface, the film appears to be a classical period adventure about the conflict between Humans and Nature, in which Spanish conquistadors head into the unknown to find treasure, only to be beaten by the unconquered jungle. But upon closer inspection, the entire picture takes place in a maddened fever dream of obsessive drives. After all, what history better represents the idea of madness itself than conquistadors setting out in a very specific direction, with hundreds of men and resources in tow, hoping to discover a place whose location is unknown, and ultimately does not exist? Many of Herzog’s greatest films are about rebels against both humanity and Nature. They yearn for an impossible achievement, perhaps out of an errant pride or vanity, but they are finally consumed and regurgitated by Nature. Herzog understood these obsessions better than most; he later experienced them while filming Fitzcarraldo (1982) and several other narratives and documentaries, including Aguirre, the Wrath of God. Here, he demonstrates his own mania by carrying out this ambitious motion picture, not by filming on a studio lot or safer location, but by driving his production to follow his subject into the heart of darkness.

When he was planning Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Herzog never intended to make a historical retelling of the life and times of Lope de Aguirre. In fact, his basic idea for the film was inspired by a children’s book that had a small section on Aguirre. What fascinated the director most was the figure’s pure lunacy. Aguirre’s reputation was already that of a sadistic and violent conquistador when he joined Don Pedro de Ursúa’s expedition down the Amazon River to locate El Dorado. It was on that expedition that Aguirre overthrew his superiors and took control. In a manic letter Herzog found in his research, Aguirre writes to King Felipe II of Spain and denounces the king, declares him “dethroned and stripped of all rights”, and renames himself “the Wrath of God”. He went on to proclaim himself “the new Emperor of El Dorado and New Spain” and led his seized expedition into the unknown. Finally, he arrived at the Atlantic, no closer to finding El Dorado, and all but a handful of his followers were dead. It was this audacity, this detachment from reality while in the remoteness of Nature, that attracted the director, and which Herzog vowed to depict in his film. “Aguirre is one of history’s great losers,” the director once explained in an interview, and the very idea of Aguirre’s uniquely obsessed mindset layered his screenplay more than historical fact. “The entire script is pure invention,” Herzog admitted in an interview. What he sought to depict was not facts and dates, but the frame of mind attributed to Aguirre, the kind adventure-seeker who pursues a wealth of riches, but more than that, pursues his own death.

Aguirre, the Wrath of God opens with prologue titles explaining that the film was derived from the diary of its monk narrator, Gaspar de Carvajal (Del Negro); however, no such diary exists. Herzog uses the framing device to give a loose sense of structure to a film comprised of long, brooding takes and chaotic internal struggles. Early in the film, expedition leader Gonzalo Pizarro (Alejandro Repullés) grows frustrated with the jungle and his group’s lack of progress. They trudge through the jungle, absurdly pushing a cannon, a horse, and carrying a woman in a sedan chair through mud and dense foliage. Pizarro resolves to halt the mission, and he places Ursúa (Ruy Guerra) in charge of a weeklong discovery scout downriver, sending forty men along, including Kinski’s wild-eyed Aguirre. His shoulders sloped to the right, twisted like his soul, Aguirre quickly takes control, placing the weak nobleman Don Fernando de Guzmán (Peter Berling) in charge, though Aguirre clearly gives the orders. Aguirre wants the city of gold for himself, likening their mission to Hernán Cortés’ conquest of Mexico. But as they descend further down the Amazonian tributaries on their ramshackle raft, several fall victim to attacks by cannibalistic natives who watch and announce, “Meat is floating by!” Starvation and dysentery also thin their ranks, and gradually Aguirre and the others are lost to madness.

Aguirre’s story fascinated Herzog, especially its themes of intense obsession, the influence of landscapes, and the search for lost cities. The director’s grandfather, Rudolf Herzog, was an archaeologist who discovered Asklepieion, the site of an ancient Greek hospital, which others had sought out for centuries to no avail. For Werner, the notion of someone seeking out a lost city was in his blood. Moreover, the director had become mesmerized by the power of natural landscapes and their ability to adapt to their surroundings. Asklepieion had once been a lavish bath; when his grandfather found it, it was buried by time underneath a field, as if Nature no longer needed it. Never was the power of landscapes more apparent than in the jungle, where the sheer force of life within the trees would stand as a kind of intangible, haunting force. Herzog felt a closeness to the material, allowing him to complete the initial screenplay “fast and abruptly and spontaneously” in a matter of days. To make his film, he received funding from a German television station, Hessischer Rundfunk, which had negotiated to show the finished film on TV the day of its debut, thereby ruining any hope of financial recompense, at least in Germany. The remainder of the film’s budget came from Herzog’s own funds, plus a loan from his brother. The entire production would be shot with just one camera, which Herzog had “liberated” from his Munich Film School after the school’s headmaster refused to lend it out. Thomas Mauch, Herzog’s cameraman on several of his previous efforts, would once again serve as the director’s cinematographer.

Before shooting began, Herzog visited South America to scout locations in the Peruvian jungle and Amazonian tributaries to ensure that what he had envisioned while writing actually existed. He found his locations, and his cast and crew arrived in Peru shortly thereafter. Filming took six weeks to complete and required camps for 450 cast and crew members, including 270 mountain natives. The locals were members of a socialist co-operative at Lauramarca and were heavily involved in Peruvian politics. They saw Herzog’s presence as an opportunity: first, to raise awareness of their situation, and second, to earn much more for their work than they were accustomed to making. Reenacting the arrival of the Spanish also appealed to the locals. History was a major part of their identity, and the Spanish conquest was still discussed among them, like “creatures from another planet had landed in spaceships and taken over the whole world,” as Herzog observed. Herzog eventually dedicated the film to one of the locals, Hombrecito, which means “little man”, who he met in the main Cusco square playing the flute. At first, Hombrecito refused to join the crew, believing that if he wasn’t there to play the flute, the people of Cusco would die. Hombrecito arrived in time, but his devotion to such a singular, self-propelled, and rather deluded idea fascinated Herzog, since his film shared similar themes.

Herzog could have shot on a studio lot or found locations closer to home, but nothing could match the ethereal presence of the Peruvian jungle, nor his actors’ authentic reactions to the jungle’s reality. Time and again during the production, Herzog’s endurance and devotion to the perfect locale were tested, and each time Herzog pushed through to achieve what he had envisioned. Though their shooting schedule was only six weeks, a week of that was spent moving the cast and crew from one camp to another, some 1,600 kilometers away, which is just one example of the lengths Herzog is willing to go to. Their camp was near the Amazon, and when the river flooded, Herzog insisted they not move; instead, the cast and crew lived on sturdy rafts locals had built for the production. He also shot the cast’s initial reactions to the flooding and included them in the film; their expressions of hopelessness at the situation speak to how completely Herzog had immersed them in the jungle. Herzog also insisted on shooting the story in sequence to convey the increasing desperation of the film’s scenario. What’s more, because Herzog’s budget was limited—a mere $370,000, “a third of which went to Kinski,” the director explained—their meager funding required spare living conditions bordering on poverty. He even sold his personal belongings (shoes, a wristwatch, etc.) to buy meals.

Herzog’s drive for authenticity put his actors’ lives at risk. During pre-production, he scouted locations for the rapids sequence and found what he believed was a relatively safe section of the river. When he tested it, his cheap raft “split in two and disintegrated, and one-half got caught in a whirlpool.” When filming the actual rapids scene, he had the local natives build a stronger raft that would survive the journey downriver. His actors boarded the raft and were set to ride the rapids. The shot had to be captured in one take because of the danger, and everyone except Mauch, who had to maneuver around the raft to capture various angles, was tethered for their own safety. When the raft ended up in the whirlpool, the actors had to be dragged through the river with ropes to escape. Elsewhere, Herzog put himself at risk. To accomplish the final shots aboard Aguirre’s doomed raft, which is infested by monkeys the way some ships are infested with rats, the director hired a local to gather hundreds of monkeys. When they began filming, the monkeys attacked. While Kinski interacted with the monkeys on film, Herzog and others off-camera were forced to endure the monkey attacks in silence to preserve the shot. Under the surface of such moments lies a darker truth: halfway through the shoot, the footage shipped to Mexico for processing was reported lost. At this news, Herzog had no reason to continue filming; he could not possibly finish on his remaining budget, nor could he continue shooting and finish the film without the processed footage. But he continued anyway, feeling that if he stopped now, the cast and crew would feel their trials were for nothing. Fortunately, some weeks later, the footage was found at a customs office in Lima, Peru, and had never left the airport for Mexico. But the notion that Herzog continued filming anyway, putting his cast and crew through hell despite believing his efforts were pointless, further aligns the director with his film’s subject.

And then there was Kinski, who was a force of Nature that nearly destroyed the entire production on several occasions. Herzog once described his relationship with Kinski as two oppositional forces of Nature that, when joined, reach a critical mass. When he was younger, Herzog had lived with Kinski for three months in a boarding house for starving artist types. Years later, with five films under his belt, Herzog thought no one but the erratic, often schizophrenic actor could play Aguirre. He sent Kinski the script, and then, late one night, received a phone call of screaming and hysterics; after an hour on the line, Herzog determined it was Kinski, who was delighted with the script. Kinski had just cancelled his theatrical Jesus tour, where he appeared at various venues such as Berlin’s Deutschlandhalle, stood on stage with nothing but a microphone, and spouted the ravings of a bona fide madman (excerpts can be seen briefly in Herzog’s documentary My Best Fiend (1999), and to greater extent in Peter Geyer’s 2008 doc Klaus Kinski: Jesus Christ the Savior). While on stage, Kinski claimed, among other things, that he was Jesus, and while hissing insults and crazed remarks at the audience, attendees hissed back. Perhaps that was the point, if there was one. However, for more shows than one would think possible, he continued to perform in his maniacal, vicious, bigoted, mean-spirited, self-styled Christlike persona, thinking himself at once godly and yet primed to be attacked by his audience. It was in this frame of mind that Kinski arrived on set for Aguirre, the Wrath of God, his god complex already well established.

In spite of Herzog’s evident environmental and budgetary troubles on-set, Kinski remained temperamental and would, as Herzog pointed out, “throw tantrums, create scandals or simply scream if he saw a mosquito.” Kinski had seen Herzog’s Even Dwarves Started Small (1970) and persisted in calling him “dwarf director” throughout the production. At one point, Kinski hit a fellow actor with a sword and, even though the actor was wearing a helmet, the force of Kinski’s thrust caused a concussion. (Of course, one has to question why the actors were given real swords, but no matter.) During another Kinski outburst, some locals were making too much noise for Kinski’s liking one night, and the actor responded by unloading three rounds from his rifle into their crowded tent; he nearly shot the finger off of one man, but he could have easily killed someone. Herzog took away Kinski’s rifle and keeps it to this day. The final incident occurred when Kinski threatened to leave the set during one of his tantrums. Herzog knew the actor was serious about leaving; he had broken contracts before. And so, the director calmly warned Kinski that the film was more important than either of them—and that if Kinski tried to leave, Herzog would get his rifle and put eight of the nine rounds into Kinski’s head, and then save the last one for himself. After this, Kinski remained calm for the rest of the day, anyway. Despite his destructive presence, Herzog admits that no one but Kinski could have played Aguirre. And though another director would have never worked with Kinski again, this was the first of five Herzog collaborations with the volatile actor. If nothing else, Herzog’s willingness to work with Kinski over the years speaks to the director’s readiness to suffer to realize his art.

]When Herzog wrapped production, there was little money left to distribute the film properly. Aguirre, the Wrath of God premiered on television on December 29, 1972, and ran concurrently in German theaters for a short time. Few countries outside Germany were interested in the film during its initial release, but those who did screen it jealously held onto their prints. A Paris theater kept a print running for two-and-a-half years before countries like Mexico and various South American countries began screening the film. Not until 1977 was the film released in the U.S. courtesy of New Yorker Films, which held screenings for the next four years. Still, the film was not the success Herzog had hoped for. This was a particularly disheartening period for the director, as Aguirre, the Wrath of God represented his first effort intended for a mass audience. Steadily, more and more critics reviewed the film, praised it, and eventually solidified its legacy. Francis Ford Coppola used it as further inspiration for Apocalypse Now in 1979, which was largely inspired by Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. But by this time, Herzog had moved on to other projects such as The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner (1974), The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), Heart of Glass (1976), and Stroszek (1977). And with each new film, the director grew his following among a growing cult of fans who knew of the German filmmaker’s work and celebrated it. Not until the release of Herzog’s masterful Fitzcarraldo in 1982 would he gain the attention of crowds beyond the arthouse, and not for another twenty years, until the mid-2000s, would Werner Herzog become a household name.

Aguirre, the Wrath of God endures because it has a spellbinding quality that entrances its audience by using real-world landscapes to represent its themes and characters. Herzog has said he uses landscapes in the same way John Ford used Monument Valley in My Darling Clementine (1946) or The Searchers (1956), to reflect his characters and their defiance of Nature for the sake of human progress. However, Ford’s characters sought to better civilization through law and order in the Wild West; Herzog’s characters are gripped by personal ambition. The director often reflects his characters’ obsessions in a physical form as well. Herzog used the mad-eyed Kinski because of some inexplicable element burning behind the actor’s eyes and his strange, almost contorted body movements, both unpredictable and appropriate within Herzog’s particular brand of filmmaking. Herzog often wanted to translate his characters’ inner madness into physical form; for Aguirre, the Wrath of God, he initially wanted to make Aguirre a hunchback to reflect his monstrosity. He decided against it, assuming his actors had enough to contend with in the jungle shoot. But Kinski’s odd, sloped posture still suggests a mental state that has seeped out and perverted his character’s body. Years later, while making The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call: New Orleans, Herzog delivered another such contortion: In the underrated 2009 film, the director slowly transforms Nicolas Cage’s drug-addled detective into a physical monster. Early on, Cage’s character injures his back while rescuing someone during Hurricane Katrina floods; the Detective resorts to drugs to ease the enduring pain, and gradually Cage’s body echoes his warped mental state, his asymmetrical shoulders almost like that of a hunchback, but certainly similar to Kinski’s performance here.

The lasting effect of Aguirre, the Wrath of God over other Herzog films is accomplished by how completely the director immerses his audience into a fever dream. Watching the film is a surreal experience that embraces the unreal. Listen to the transfixing music by German electronic band Popol Vuh, who scored half a dozen Herzog films through The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser in the coming years. They use a choir organ to create an unnerving, apostolic atmosphere in scenes, as if something profound and horrifying is taking place before our eyes, yet deserving of our reverence. Herzog wanted to implant a dreamlike unease throughout the film, largely focused on the jungle’s mystique. He sought to create a jungle that was “so strange you just cannot trust it.” He also included an audio track of jungle bird sounds in the background, and after a time it becomes almost white noise, except when he removes it and leaves the audience with only a frightening silence—which means local tribes have surrounded the Spanish. Nowhere is safe. On the rafts, Aguirre’s crew finds dead bodies, as arrows were shot in silence from somewhere deep in the forest. On land, cannibal camps have human remains strung up as decoration, whereas in the forest, traps lift victims into the branches, leaving only blood to drop onto the leaves below. In its wild condition, the jungle is both merciless and beautiful.

Elsewhere, his film operates in a purely hallucinatory state. Herzog shows us impossible things, and we can never quite know if they are real. At one point, a man is counting to ten. Behind him, another man swings a sword and decapitates him. The head, which rolls several feet away, finishes its thought: “Ten.” Then there’s a haunting moment when Ursúa’s wife, who wears a blue dress throughout, appears wraithlike in a white and gold gown, then disappears into the rain forest. Has she died, leaving her spirit to walk into the forest? Has she merely given up and resolved to submit herself as a meal to the cannibalistic natives who inhabit the jungle? Another nightmare moment in the film occurs when, as his raft descends the river, Aguirre’s men see a boat high in a tree. The moment is eerie, as water levels could never have lifted a boat up there. We can only wonder whether it fell from the sky or whether some creature from inside the rain forest lifted it up and dropped it. Herzog executed the moment by building a real boat in the tree, assembling it in five sections, and using an elaborate scaffold around the tree. The effect and implementation anticipate Herzog’s otherworldly uses for a boat in Fitzcarraldo. Finally, a slave aboard the raft remarks that the boat is not real, and that the forest is not real. And then a native’s arrow strikes him in the leg. He does not react; rather, he says the arrow is not real either.

In the film’s final moments, the camera circles around Aguirre on his doomed raft. Its obsessed captain looks into the face of a monkey, proclaims he will endure, survive, and conquer the continent. His delusion and insanity are absolute. He tosses the monkey aside and looks to the sky for hope. No one is listening, perhaps not even his God. Herzog cuts to the Sun blaring down on Aguirre’s raft; he is isolated on the river, alone and hopeless. None of the director’s films, more than Aguirre, the Wrath of God, pairs its theme of obsession with such an extreme sense of surrealism, which, in turn, underscores the notion that those gripped by their obsessions exist in an almost dreamlike state of madness. Often, the actions or extreme conditions surrounding Herzog’s subjects implicate his characters’ fanaticism, but rarely has Herzog engineered such an ethereal, other-worldly state beyond that of his first true masterpiece. Many of Herzog’s films involve various forms of obsession, whether it be over an impossible idea, such as a lost city of gold, or the director’s almost terminal desire to complete an authentic production. Aguirre, the Wrath of God shows Herzog’s mutual affection and abhorrence for Nature, how it remains ambivalent to human desire and cruel to our often maniacal ambitions, and yet how we continue to think, through our own deluded perspective, that we can somehow conquer it.

Bibliography:

Cronin, Paul. Herzog on Herzog. London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2002.

Minta, Stephen. Aguirre: The Re-Creation of a Sixteenth-Century Journey Across South America. New York: H. Holt, 1994, c1993.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review