The Definitives

A Touch of Zen (1971)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

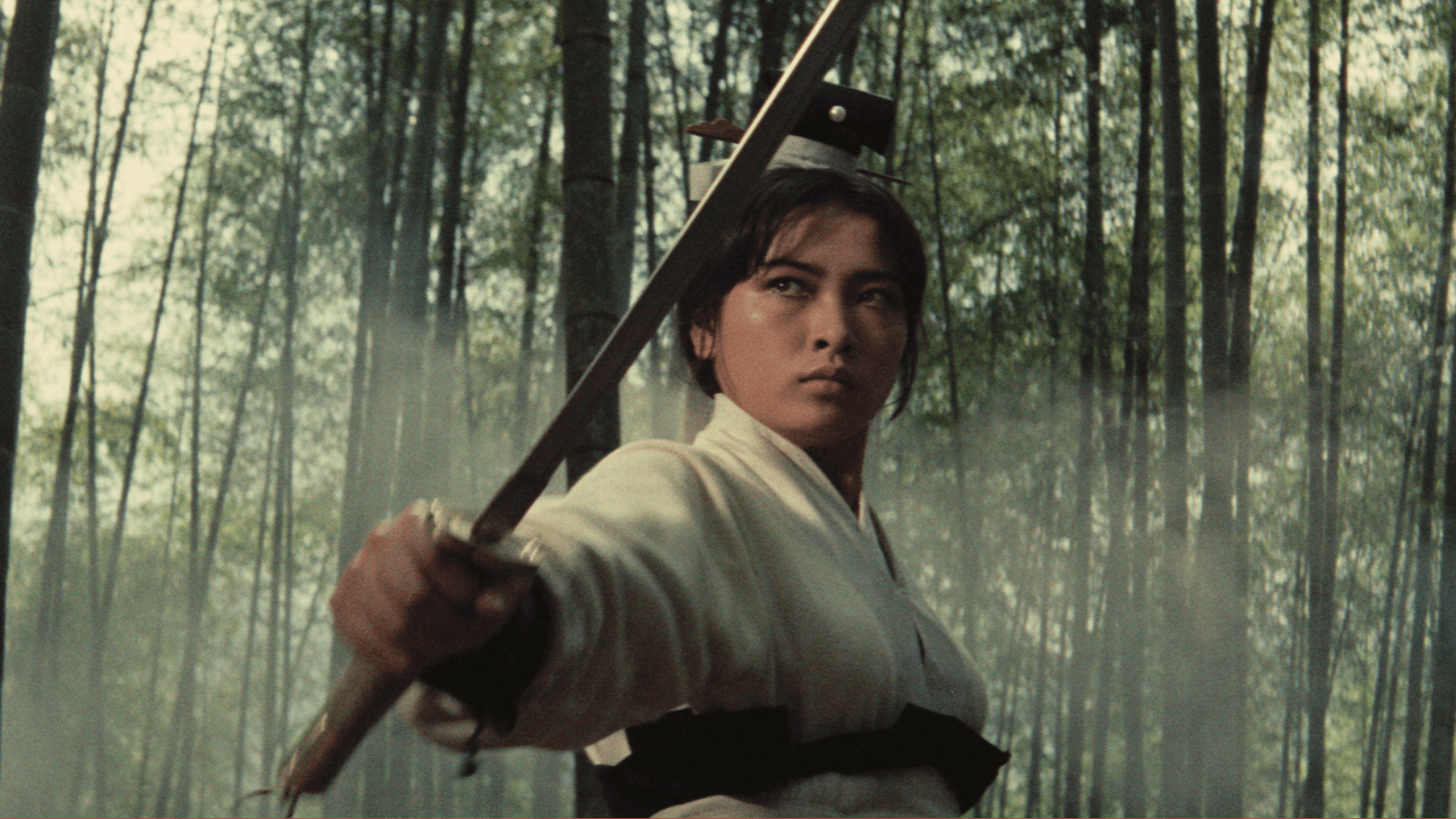

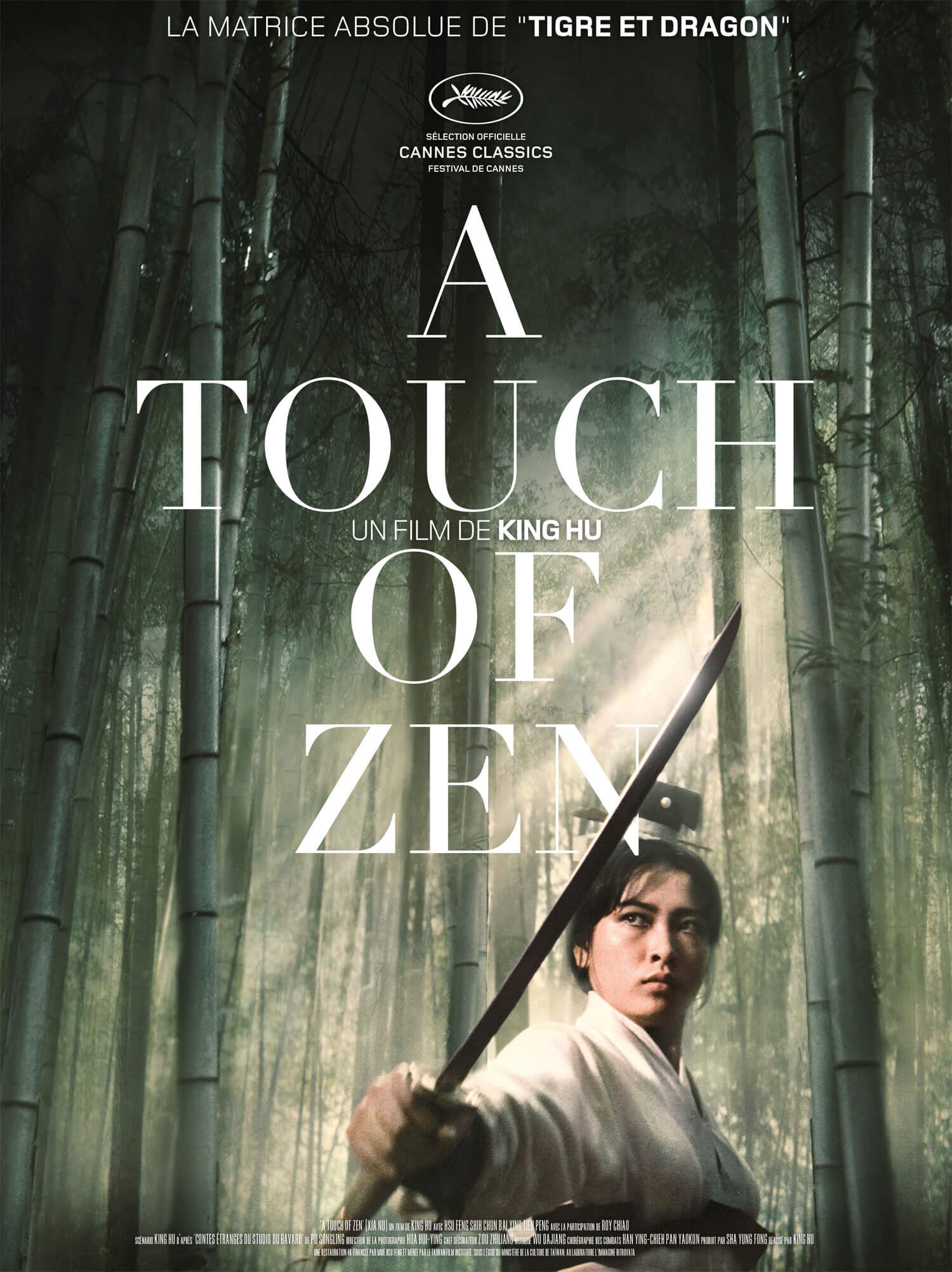

A Touch of Zen explores the boundaries of wuxia, a subgenre of Chinese martial-arts cinema usually rooted in notions of personal honor and chivalry. King Hu’s most acclaimed film—a three-hour epic of lyrical fight choreography, subterfuge, romantic entanglement, and poetic aestheticism—reaches beyond the genre’s focus on heroes and gallantry in search of something more transcendent. Its warriors perform in operatic fight sequences and often defy the rules of earthbound combat, but Hu’s contemplative imagination takes the film even further. The writer-director rethinks the root assumptions of wuxia to craft a female warrior, played by iconic actress and producer Hsu Feng, into an emblem of humanist searching. In doing so, Hu expands upon wuxia’s typical gender roles for women and posits an alternative marked by Zen Buddhism, genre variation, and a scale unseen in wuxia cinema upon the film’s release in 1971. A Touch of Zen contains enough story for two films, but by combining them into a singular, existential saga with experimental stylistic flourishes throughout, Hu created what scholar Stephen Teo hailed as wuxia’s “first true masterpiece in the genre.” At the same time, Hu’s film is also an anomaly of ambition and metaphysical searching that introduces ideas and perspectives rare to the genre, and Hu’s career, before or since.

To appreciate King Hu’s importance to wuxia, some context about the genre is necessary. The term wuxia comprises two components: wu signifies war and militaristic characteristics, while xia indicates themes of righteousness, heroism, chivalry, and honorable warriors. Together, they denote narratives accented by traveling knights-errant who pursue gallant causes. A subgenre of the Chinese martial arts film, wuxia emerged in the 1920s and drew influence from Chinese opera styles, particularly in their elaborate, dancelike, and often gravity-defying fight scenes. Although wuxia principles have literary antecedents that date back to the Han dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE), the term originated in Japan at the turn of the twentieth century. It first appeared in Shunro Oshikawa’s 1902 adventure novel, Bukyo no Nihon, which in Chinese translates to Wuxia zhi Riben (or Heroic Japan in English), with bukyo as the Japanese equivalent of wuxia. When Chinese students and writers abroad in Japan returned with the word wuxia, they encouraged its use. The term signaled a modernist shift into the military and scientific advancements demonstrated by the Meiji period in Japan, which had made them major players on the world stage. The term also symbolized what China wanted to become. In China, the word became so common that many no longer associate wuxia with its Japanese origins. Even Japan’s narrative equivalent has since moved on from using bukyo to adopting the term chambara (onomatopoeia for the sound of clanging swords) instead.

Wuxia should not be confused with kung fu cinema, though both wuxia and kung fu movies could be categorized as martial arts films. The former denotes sword-fighting films, often with touches of dancelike action derived from Chinese opera, whereas the latter indicates purely hand-to-hand (and foot-to-foot) combat films. For much of the twentieth century, wuxia remained limited to Hong Kong and Taiwan cinemas and absent in mainland China because, as Teo notes, it inspired “superstitious thinking.” According to scholar Ho-Chak Law, it used “elegiac portrayals of the ancient past that conflicted with the concurrent cultural and political values.” This resulted in a period without wuxia films in mainland China between Zhang Shichuan’s Burning of the Red Lotus Temple (1931) and Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002). In the earliest examples, the actors’ gestures mirror the dance movements and acrobatics used in the Peking opera. Many wuxia actors either studied opera or learned its performance styles for their onscreen roles. However, in these early films, the martial artistry used in Chinese opera was transferred onto the screen without considering the medium, resulting in stagy performances that looked like unnatural tableaus. It wasn’t until Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers sought to reformat wuxia, with a new focus on realistic violence designed for cinema, that wuxia started to resemble what it is today.

The Shaw Brothers Studio—modeled after Warner Bros., yet operated by two of four brothers, Run Run and Runde Shaw—popularized wuxia films in the 1960s with their factory-like production unit that made and distributed upwards of forty films a year. After the Chinese opera film had disappeared from cinemas, the Shaw Brothers launched a new initiative in a veritable manifesto dubbed “The New Century of Wuxia” at their studio. The movement called for a fresh take on wuxia films, eliminating the stagelike artifice of filmed operas in favor of the popular violence and action in Hollywood and Japanese films. King Hu started at Shaw in 1958, where he learned the craft of filmmaking in various occupations, including set decorator, actor, writer, and assistant director. He eventually made his directing debut with Sons of the Good Earth (1965), about a peasant army fighting Japanese troops in 1937 during the Sino-Japanese War. But it was his next film, and first wuxia film, Come Drink With Me (1966), that established Hu as a unique filmmaker. Hu’s perspective remained unlike anyone else at Shaw because he sought to depict an accurate cultural history, albeit one distinctly interpreted from his poetic stylization and meticulous attention to every conceivable detail of the production.

The Shaw Brothers Studio—modeled after Warner Bros., yet operated by two of four brothers, Run Run and Runde Shaw—popularized wuxia films in the 1960s with their factory-like production unit that made and distributed upwards of forty films a year. After the Chinese opera film had disappeared from cinemas, the Shaw Brothers launched a new initiative in a veritable manifesto dubbed “The New Century of Wuxia” at their studio. The movement called for a fresh take on wuxia films, eliminating the stagelike artifice of filmed operas in favor of the popular violence and action in Hollywood and Japanese films. King Hu started at Shaw in 1958, where he learned the craft of filmmaking in various occupations, including set decorator, actor, writer, and assistant director. He eventually made his directing debut with Sons of the Good Earth (1965), about a peasant army fighting Japanese troops in 1937 during the Sino-Japanese War. But it was his next film, and first wuxia film, Come Drink With Me (1966), that established Hu as a unique filmmaker. Hu’s perspective remained unlike anyone else at Shaw because he sought to depict an accurate cultural history, albeit one distinctly interpreted from his poetic stylization and meticulous attention to every conceivable detail of the production.

Born into a politically connected and well-educated Beijing family in 1932, Hu grew up as an artist interested in history and classical Chinese texts. After completing his secondary education at Peking University, he emigrated to Hong Kong in 1949, where he spent nearly a decade in a series of empty jobs before landing at Shaw Brothers Studio. After his first two films, Hu moved to Taiwan, where he established the production company Union Film. There, he developed his most famous early breakthroughs, including Dragon Inn (1967) and A Touch of Zen, while also significantly crafting what we now know as wuxia. Hu also began the trend of crediting a “martial arts director” or “action choreographer” in Hong Kong and Taiwanese martial arts cinema. However, his films demonstrated that he did more than follow the traditions of wuxia, only better; instead, he created a new cinematic aesthetic that has been copied and repurposed by filmmakers from Ang Lee (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, 2000) to Zhang Yimou (Hero, 2002) to Hou Hsiao-hsien (The Assassin, 2015) to Destin Daniel Cretton (Shang Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, 2021). Hu’s films remain unique for how he takes elements of Buddhism with Chinese history, literature, and painting, and combines them with martial arts adventure. But Hu also oversaw every aspect of his productions, including music, costumes, lighting, editing, props, and sets, ensuring that each element worked in unison with his themes.

In his book King Hu in His Own Words, the director states he sought “the utmost utilization of film language” by aligning pristine formal techniques and narrative function. He sought to deploy the traits of Chinese opera and integrate them into an elevated cinema that reached the heights of fine art. This is never more apparent than in A Touch of Zen, where Hu’s distinct aesthetic infuses martial arts with operatic forms and a grand, transcendent narrative to match. Specifically, Law observes that the director draws from operatic conventions such as “appropriated acrobatic set pieces (taozi) and luogu (literally meaning ‘gongs and drums’) percussion patterns” that demonstrate Hu’s “fascination with the visual and musical symbolisms inherent in Chinese opera.” But the director doesn’t use these traits in the same manner as in opera. For instance, the Peking opera used luogu percussion to inform the actors’ behaviors and reveal the interior state of the characters to viewers too far away from the stage to read a facial expression. In contrast, Hu has the ability to use close-ups of the actor’s expression, and so he employs the same sounds in purely musical terms.

Moreover, Hu demanded an original music score that would seem to reverberate with the acoustic spaces depicted in the film. This was strange for a couple of reasons. For instance, there was a long history in Chinese cinema, going back to early silents, of filmmakers using prerecorded music to score their films. Law notes that established music “from European symphonic traditions, late nineteenth century light operas, overtures, waltzes, and marches, as well as classical Hollywood film scores and contemporary Chinese instrumental pieces are common in the films of that period.” Filmmakers at the Shaw Brothers Studio, too, were content with using canned music. But for A Touch of Zen, Hu and composers Wu Ta-chiang and Lo Ming-tao designed luogu percussions to give dancelike physicality to swordfights and deep, reverberating strings to accompany the Zen monk characters. The score provides more than background noise; it supplies another artistic layer that harmonizes with Hu’s other aesthetic choices. The director’s treatment of music became an accented trait of his cinematic style of repurposing operatic tools for the cinema. By extension, they had a formative influence by establishing the subgenre’s grammar for other filmmakers.

Moreover, Hu demanded an original music score that would seem to reverberate with the acoustic spaces depicted in the film. This was strange for a couple of reasons. For instance, there was a long history in Chinese cinema, going back to early silents, of filmmakers using prerecorded music to score their films. Law notes that established music “from European symphonic traditions, late nineteenth century light operas, overtures, waltzes, and marches, as well as classical Hollywood film scores and contemporary Chinese instrumental pieces are common in the films of that period.” Filmmakers at the Shaw Brothers Studio, too, were content with using canned music. But for A Touch of Zen, Hu and composers Wu Ta-chiang and Lo Ming-tao designed luogu percussions to give dancelike physicality to swordfights and deep, reverberating strings to accompany the Zen monk characters. The score provides more than background noise; it supplies another artistic layer that harmonizes with Hu’s other aesthetic choices. The director’s treatment of music became an accented trait of his cinematic style of repurposing operatic tools for the cinema. By extension, they had a formative influence by establishing the subgenre’s grammar for other filmmakers.

Similarly, Hu’s use of the opera’s acrobatic performance in heightened dramatic moments does more than add the expressive flourishes of stage conventions; it adds a rhythm that functions in harmony with the cinematography and set design. Hu and choreographer Han Ying-Chieh designed combat scenes with these elements in mind, starting with Han’s arrangement, which Hu would then storyboard and cinematographer Hua Hui-ying would capture. Hu and co-editor Wing Chin-chen then edited the sequence according to Hu’s storyboarded plan, complete with rhythmic variations, like a composer writing a score. This sort of controlled planning left no room for actors to improvise their performance or movements, and it highlights what Hu called the “purity” of movement—not so much as a fight sequence but as a visual appreciation of how the body and camera work together to emphasize the physicality of the gestures performed. Come Drink with Me star Cheng Pei-Pei told Law, “Hu was mainly concerned with the visual representation of tempo and rhythm, and he employed his film editing skills to further manipulate it… Hu was very manipulative in filmmaking.” The almost musical structure of combat in A Touch of Zen might seem to drain them of spontaneity, except the arrangement is brimming with life.

Hu based his screenplay on the story “Xianü” from Pu Songling’s anthology, Liaozhai Zhiyi (known in English as Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio). The original story’s title refers to the xia quality of chivalrousness in the gendered feminine form, following a female knight-errant. Hu frequently centered his films around female protagonists, departing from the standard, masculine roles of knights-errant demonstrated in Hong Kong cinema by filmmakers such as Chang Cheh (Five Deadly Venoms, 1978), a Shaw Brothers Studio mainstay. Teo points out that it’s worth asking “whether the prominence [Hu] gave to the female knight-errant was eventually a reaction against the trend of the masculine hero which gathered momentum under [Chang’s] direction.” After all, Hu popularized women warriors in his films, foregrounding the traditionally feminine and masculine attributes that defined the inner duality of such a character. He drew directly from the virtuous hero known as Thirteenth Sister from the novel A Tale of Heroic Lovers, first published in 1878, about a woman who seeks vengeance for the wrongful death of her father by corrupt officials. In A Touch of Zen, Hu’s view of heroism considers the xia portion of wuxia not only for his film’s central warrior but also a scholar, and not only for victory in battle but for self-understanding. Although many wuxia films dwell on stylized action first, Hu sought a greater balance between the two components of wuxia, so that when a fight occurs, the hero fights for a noble and even aspirationally transcendental cause—an ideal rooted in Buddist philosophy.

However, unlike Thirteenth Sister, Hu’s hero in A Touch of Zen, Yang Hui-zhen (Hsu Feng), the film’s female knight-errant, does not give up her heroic role to become a wife as the protagonist of A Tale of Heroic Lovers does. Rather, Hu questions the gendered assumptions about knight-errantry and enters into an existential and metaphysical discussion of heroism, the necessity of violence, and the fluid nature of identity. Yang adopts several roles in the film. Besides being a knight-errant, she pretends to be a ghost, becomes a tenuous lover and child-bearer for her foil, the poor scholar Gu Sheng-zhai (Shih Chun), and later adopts a monastic life. Hu’s interest in the ever-shifting identities of his characters links with his exploration of Zen and what Teo describes as “an improvisation in the act of self-fashioning within the film text.” Submitting to Zen, then, becomes an acceptance that roles such as knight-errant or scholar are merely tropes or social constructions—earthly states—and that they can be deviated from. One attains enlightenment in this understanding of Zen by transcending established roles and carving out an identity through a moral vision beyond explanation. Hu wrote, “I don’t have the least intention of being didactic or evangelical in my approach to this matter. All I am interested in is presenting the flavor of a particular experience.” In other words, Hu’s “touch of Zen” and his remarks on identity should not be intellectualized but felt.

However, unlike Thirteenth Sister, Hu’s hero in A Touch of Zen, Yang Hui-zhen (Hsu Feng), the film’s female knight-errant, does not give up her heroic role to become a wife as the protagonist of A Tale of Heroic Lovers does. Rather, Hu questions the gendered assumptions about knight-errantry and enters into an existential and metaphysical discussion of heroism, the necessity of violence, and the fluid nature of identity. Yang adopts several roles in the film. Besides being a knight-errant, she pretends to be a ghost, becomes a tenuous lover and child-bearer for her foil, the poor scholar Gu Sheng-zhai (Shih Chun), and later adopts a monastic life. Hu’s interest in the ever-shifting identities of his characters links with his exploration of Zen and what Teo describes as “an improvisation in the act of self-fashioning within the film text.” Submitting to Zen, then, becomes an acceptance that roles such as knight-errant or scholar are merely tropes or social constructions—earthly states—and that they can be deviated from. One attains enlightenment in this understanding of Zen by transcending established roles and carving out an identity through a moral vision beyond explanation. Hu wrote, “I don’t have the least intention of being didactic or evangelical in my approach to this matter. All I am interested in is presenting the flavor of a particular experience.” In other words, Hu’s “touch of Zen” and his remarks on identity should not be intellectualized but felt.

The story finds Gu living with his widowed mother in a small home within the walls of the abandoned, dilapidated Jing Lu Fort. Yang has secretly moved into the nearby ruins of the General’s Mansion, careful to keep out of sight, prompting Gu to believe there’s a ghost haunting the property. But Gu’s mother (Zhang Bing-yu), playing matchmaker and hoping for a grandchild to carry on the family line, soon introduces Gu to Yang. Although she rejects his marriage proposal, Yang becomes endeared to Gu after she helps take care of his sick mother. At the same time, a stranger named Ouyang Nian (Tien Peng) commissions Gu to paint his portrait, using this as a pretense to snoop around the fort’s ruins and around town for Yang—though why remains unclear at this point. While doing so, Ouyang meets a blind fortune-teller, Shi (Bai Ying), and tests whether he’s truly blind. Suspicious, Ouyang also confronts Yang and Gu, storming into their room the morning after they make love. Yang responds with a sword fight, revealing that she’s not just a romantic prospect for Gu but a warrior out to avenge her father, who offended Eunuch Wei and whose entire family was ordered to death by the ruthless Eastern Depot—a group of secret police run by the eunuchs, despotic imperial civil servants. “It is not too much to say that the power of the Eastern Depot exceeded that of the modern Gestapo,” Hu wrote, “and the very mention of its name was enough to cause innocent people to shake in their boots.” Ouyang is an Eastern Depot agent, and a fearsome opponent Yang has faced before. A flashback reveals that Yang escaped the Eastern Depot with two of her father’s allies, Generals Lu (Xue Han) and Shi, thanks to the help of a Zen master, Abbot Hui-yuan (Roy Chiao), who confronted and fought off Ouyang.

A Touch of Zen’s thrilling fights stand among some of the wuxia genre’s most dazzling sequences, and none is more iconic than the confrontation in a bamboo forest. Many filmmakers have tried to replicate its sheer spectacle, but few have captured Hu’s balance of pacing and beauty. The sequence comes about when Gu, now aware of Yang’s identity and the stakes, joins with Yang and encourages her cohorts to stop Ouyang before he can contact an Eastern Depot party sent by their commander, Men Da (Wang Rui). Yang and Shi confront Ouyang, and what unfolds is a visually wondrous action sequence that finds the combatants flying through the air, leaping like kangaroo mice, slicing at bamboo trees to block their path, flipping over opponents, and throwing swords and projectiles. Still, regardless of how often Hu’s visual style is characterized by his action scenes and their operatic presentation, other sequences in A Touch of Zen reveal his more nuanced tendencies as a visualist. He captures sunlight peering through the bamboo trees, creating beams that illuminate mist for an atmospheric effect. Fog in the tall grasses around the fort also seems to glow in the morning light. Or note his wide-angle lenses that, during his frequent long panning shots, seem to unfurl the frame like a scroll. Hua Hui-ying also pans over scenes that observe Nature, which Hu imbued with symbolic meaning. Take how the morning after Gu and Yang make love, the camera finds another couple, two turtles, lovers no doubt, nestled near a pond. Or how scattering birds often usher the frame forward as the camera moves through the fort. The most pointed example must be the film’s first images of spiders in their webs, catching prey—an allusion to the film’s centerpiece: an elaborate battle at the fort.

Indeed, the story builds to an intricate trap, followed by a battle in the fort ruins between Yang’s outnumbered allies and the Eastern Depot. Paraphrasing Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Gu puts his education to work when he says, “Know thy enemy, and self is at hand,” and concocts an elaborate scheme. First, Gu enlists his mother to spread rumors that the fort is haunted, implanting dread among the Eastern Depot’s red-sashed footsoldiers. Gu also spreads the notion that Men Da might be kidnapped, so when they enter the fort at night to find Yang, Men Da accompanies his men for safety. Once inside the fort amid the crumbled buildings and overgrown grasses, the spider’s web has entangled them in a series of illusions that suggest a ghostly enemy. Ringing bells tied to invisible strings. Spiritual firelight in the woods. Ghostly figures made out of dummies. Hidden arrow launchers. Doors that open and shut on their own. And the coup de grâce, a funeral tablet with Yang’s name, on which she sprays Men Da’s blood in poetic revenge at the battle’s end. While the setup of a few skilled combatants using deception to gain a tactical advantage against an invading enemy recalls Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954), Hu doesn’t explore Gu’s plan in advance. Instead, he shows the contraptions and trickery in the moment—and in the aftermath, when Gu emerges from his hiding spot and surveys the scene, laughing with riotous pride over their victory. But the sudden reality of the bloodshed strikes him into sober silence.

Indeed, the story builds to an intricate trap, followed by a battle in the fort ruins between Yang’s outnumbered allies and the Eastern Depot. Paraphrasing Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Gu puts his education to work when he says, “Know thy enemy, and self is at hand,” and concocts an elaborate scheme. First, Gu enlists his mother to spread rumors that the fort is haunted, implanting dread among the Eastern Depot’s red-sashed footsoldiers. Gu also spreads the notion that Men Da might be kidnapped, so when they enter the fort at night to find Yang, Men Da accompanies his men for safety. Once inside the fort amid the crumbled buildings and overgrown grasses, the spider’s web has entangled them in a series of illusions that suggest a ghostly enemy. Ringing bells tied to invisible strings. Spiritual firelight in the woods. Ghostly figures made out of dummies. Hidden arrow launchers. Doors that open and shut on their own. And the coup de grâce, a funeral tablet with Yang’s name, on which she sprays Men Da’s blood in poetic revenge at the battle’s end. While the setup of a few skilled combatants using deception to gain a tactical advantage against an invading enemy recalls Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954), Hu doesn’t explore Gu’s plan in advance. Instead, he shows the contraptions and trickery in the moment—and in the aftermath, when Gu emerges from his hiding spot and surveys the scene, laughing with riotous pride over their victory. But the sudden reality of the bloodshed strikes him into sober silence.

If Gu’s reactions in these scenes seem comically exaggerated, it’s because, along with the dancelike fighting and musicality of A Touch of Zen, the film borrows from Chinese opera in its use of characters who express clear emotions on their face in a larger-than-life format. Hu’s camera often holds a close-up shot of a statuelike expression to make the emotional pitch unmistakable and, as Law notes, integrates “some visual, verbal, or technical characteristics of specific Peking opera role types.” The association with stock opera tropes and gestures lends boldness and theatricality to Hu’s wuxia films. Even the film’s few moments of humor take on an emphatic style, evidenced in the slapstick gags in the first third—particularly those involving Gu’s dumbfoundedness over Yang’s beauty and embarrassment when he learns she isn’t a ghost. The approach can seem unnatural and expressionist for audiences not accustomed to theatrical acting styles—comparable to how early Hollywood talkies seem emphatic to today’s eyes—but these choices are intentional. And when considered along with Hu’s interest in historical accuracy, costumes, and production design, the theatrical acting creates not a contrast of styles but a unique aesthetic vision that other filmmakers would attempt to repeat.

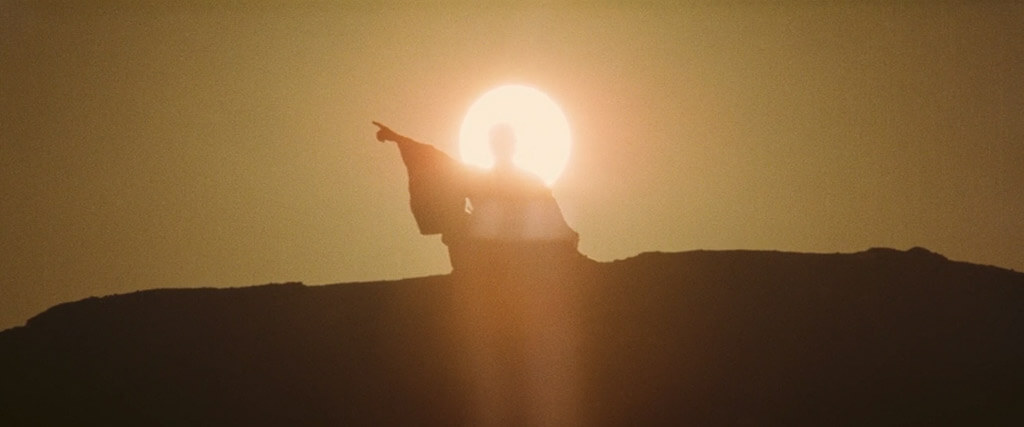

If A Touch of Zen were a more conventional film, it might have ended not long after the fort battle, after which Yang disappears. Hoping to rekindle their love affair, Gu searches for Yang for many months before discovering she has entered Abbot Hui-yuan’s Zen monastery and, in the interim, has given birth to Gu’s child. “The Gu family has its heir,” she writes him in a note that accompanies their baby, but they will not marry, nor will Yang raise their child. With Gu’s family line secured and Yang’s future safe in Abbot Hui-yuan’s monastery, this might be a pleasant enough ending. Except, the remaining segment plays like a coda that changes everything that came before. Hui-yuan dispatches Yang and Shi to protect Gu from the imperial guard, which has circulated wanted posters with Gu’s face. Yang and Shi intervene to protect Gu and the baby from Xu Zheng-qing (Cao Jian), an imperial commander who outmatches both of them, requiring Hui-yuan to intervene. After a confrontation, Xu appears defeated and feigns allegiance to the abbot. But it’s a deception, and Xu stabs him. Reeling back, Hui-yuan strikes a blow to Xu in the forehead, causing him to see hallucinations and golden particles in the air. Hui-yuan stumbles away and moments later appears on a ledge, oozing golden blood from his stab wound. Xu watches as Hui-yuan seems to achieve a state of Zen transcendence into a metaphysical realm. Earlier in the film, A Touch of Zen suggests Hui-yuan was close to nirvana during the sole flashback, when Ouyang sees the abbot’s head framed by sunlight, implying that the Eastern Depot villain recognizes the monk’s enlightened path and his own shame. The film ends with a heightened version of that image, the last thing Xu sees before he dies—a silhouetted Hui-yuan, his head haloed by the Sun, achieving nirvana.

Even though A Touch of Zen was released in two parts, half in 1970 and the conclusion in 1971, Hu continued working out the details of his finale until just weeks before the second half reached theaters. When the two installments debuted in Taiwan, the result was a box-office bomb. The film also flopped in Hong Kong, where it was dramatically altered into a single two-and-a-half-hour feature. Because of this commercial failure, Hu never quite had the same ambition after A Touch of Zen, and for the immediate future, no wuxia film would ever be quite so daring. Hu’s production company, Union Films, lost a significant amount of capital from this magnum opus, and it responded by producing fewer wuxia films in favor of contemporary-set dramas. Hu would continue making wuxia films, including The Fate of Lee Khan (1973) and The Valiant Ones (1975), but they remained far more grounded in typical notions of chivalry, politics, and strategy. Even when his films hinted at mysticism, such as the powerful scrolls sought in Raining in the Mountain (1979), Hu never again tried anything so experimental as A Touch of Zen’s finale. Nor did Hu ever give his female knights-errant the same attention; however, directors such as Ang Lee and Hou Hsiao-hsien would continue Hu’s interest in women warriors.

Even though A Touch of Zen was released in two parts, half in 1970 and the conclusion in 1971, Hu continued working out the details of his finale until just weeks before the second half reached theaters. When the two installments debuted in Taiwan, the result was a box-office bomb. The film also flopped in Hong Kong, where it was dramatically altered into a single two-and-a-half-hour feature. Because of this commercial failure, Hu never quite had the same ambition after A Touch of Zen, and for the immediate future, no wuxia film would ever be quite so daring. Hu’s production company, Union Films, lost a significant amount of capital from this magnum opus, and it responded by producing fewer wuxia films in favor of contemporary-set dramas. Hu would continue making wuxia films, including The Fate of Lee Khan (1973) and The Valiant Ones (1975), but they remained far more grounded in typical notions of chivalry, politics, and strategy. Even when his films hinted at mysticism, such as the powerful scrolls sought in Raining in the Mountain (1979), Hu never again tried anything so experimental as A Touch of Zen’s finale. Nor did Hu ever give his female knights-errant the same attention; however, directors such as Ang Lee and Hou Hsiao-hsien would continue Hu’s interest in women warriors.

Hu described his most significant challenge of the production as portraying a state of Zen. No dialogue could explain away what Hui-yuan achieves in the final images, and Hu resists any clarity, leaving the film’s ending open to interpretation. Given Xu’s wounds and apparent hallucination, Hui-yuan’s transcendence may have been illusory, resulting from Xu’s head trauma. Then again, this is unlikely given that Yang sees Hui-yuan in this state as well. Haloed, Hui-yuan points screen left, as though directing Yang to the monastery that appears in the next shot, instilling A Touch of Zen with a final emphasis on the metaphysical realm—both in Hui-yuan’s transformation and the implication that Yang should and will follow a similar path. The overwhelming force of this ending leaves the viewer with a sense that the first two-thirds of the film are less about Gu and more about Yang’s eventual path to Zen. To be sure, the classical adventure setup ends once Gu helps defeat the Eastern Depot and secures his family line. But Hu defies traditional martial arts film narrative in two ways: First, he makes Yang the central warrior for much of the film, and, in the end, he resists turning her into the usual female trope (wife, mother). Instead, she occupies an unconventional role by supplying Gu with an heir but refusing to marry him or raise the child, and then seeking enlightenment at the Zen monastery. Her choices suggest she has somewhat bowed to tradition by giving Gu a child to continue his family line, but she reserves the rest of her life for herself in a feminist flourish. Second, Hu’s focus on Zen sets aside wuxia’s typical concerns with chivalry and resolves there are more existential stakes.

In a sense, A Touch of Zen, often cited as the pinnacle of wuxia, is an unorthodox example of the genre. While Hu’s central characters search for their identity and demonstrate that they transcend any simple descriptor, so too does the film. Its various strains become almost postmodern in their unique combination: a ghost story, a political thriller, a revenge story, a mystery, a romance, and an existential search for selfhood. Unlike Gu, whose clear objectives prove traditionalist, Yang remains complex, serving as a female knight-errant who yearns for Buddhist transcendence—a state not often reserved for women in wuxia films before 1971. Although Hu stops short of depicting Yang in the shimmering transcendental light, Hui-yuan’s gesture to the monastery implies that her journey in Zen continues. Uncommonly structured and grand in scope, A Touch of Zen is Hu’s crowning achievement because the director rises above most other wuxia examples by suggesting that transcendence cannot be achieved in martial arts or honor alone, and what is more, it’s not an ambition reserved exclusively for male knights-errant. Hu recognizes the basic human desire to achieve selfhood and explores that notion in an epic drawn from history, philosophy, and artistic tradition, at once reconfiguring yet emblematizing wuxia for filmmakers to come.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on August 18, 2022.)

Bibliography:

Law, Ho-Chak. “King Hu’s Cinema Opera in His Early Wuxia Films.” Music and the Moving Image, vol. 7, no. 3, 2014, pp. 24–40. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5406/musimoviimag.7.3.0024. Accessed 10 July 2022.

Hu, King. King Hu in His Own Words. CEC (Udine), 2013.

—. “Notes on A Touch of Zen.” The Criterion Collection, 22 July 2016. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/4157-notes-on-a-touch-of-zen. Accessed 15 July 2022.

Teo, Stephen. Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition. Second Edition. Edinburgh University Press, 2009.

—. King Hu’s A Touch of Zen. (The New Hong Kong Cinema). Hong Kong University Press, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review