The Definitives

A Serious Man (2009)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

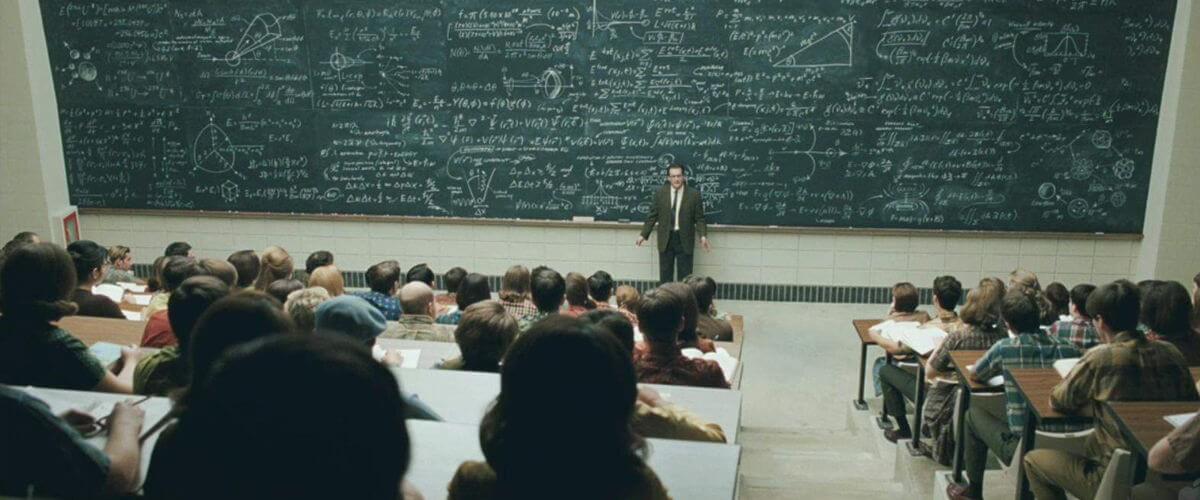

In the days preceding his son’s bar mitzvah, Jewish physics professor Larry Gopnik endures a series of misfortunes that, in their entirety, would drive anyone to madness. To find some rationale for his exceptionally bad luck, he speaks to several rabbis and asks Hashem (Hebrew for “the name”) what message he should take away from his misery. There must be some purpose to his suffering, some great lesson being taught to him. Despite his prayers and pleading, no answer comes. Later, during one of his lectures, Larry explains Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle to a room of befuddled students, insisting, “Even if you can’t figure it out, you’re still responsible for it on the midterm.” Filmmakers Joel and Ethan Coen wade through questions and offer no answers in A Serious Man, a film that solidifies their career-long pursuit to illustrate the futility in searching for a grand meaning that ties everything together.

Appropriately, the film has proven inscrutable for some audiences and profoundly revealing for others. In presenting a visual text ripe with metaphor and puzzlework, its inherent perplexity also summarizes a thematic schema that flows through the Coens’ every film since their splendid debut in 1984, Blood Simple. Indeed, even as Larry preaches the Uncertainty Principal to his students, he fails to apply the equation’s notion that one can never really know “what’s going on” to his own life. If only he could see that there are only assumptions and perspective; how persistently one clings to those ideas, however intangible they may be, remains the deciding factor of their importance. The film seems to argue the old adage that there are two sides to every story. There are two possibilities for every event in Larry Gopnik’s life throughout the course of the film. The central questions to the narrative concern finding some reconciliation between belief and doubt, known and unknown, certain and uncertain. With the inclusion of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle and also Schrödinger’s Cat Paradox as crucial symbolic elements to the plot, the Coens suggest that nothing can be truly known, only speculated on; therefore, asking questions proves a pointless act. Unless, of course, Larry assigns his own significance to the events in his life. But “I don’t know” and “What’s going on?” are Larry’s foremost expressions repeated throughout the film, and some audiences have walked away uttering much the same.

Not unlike their 2007 masterwork No Country for Old Men, the means to unlocking this film exists within the first scenes. Whereas Tommy Lee Jones’ narration gave way to the human despair and savagery that followed it, the prologue in A Serious Man tells a fable to help illustrate the purpose of the ensuing film: It recounts the tale of a Jewish couple in an old Eastern European village who argue about whether or not their noble guest, played by Fyvush Finkel, is a dybbuk (a Jewish specter). The scene appears in a smaller aspect ratio shaped for early cinema, the corners foggily suggesting a red iris that gives the scene a timeless, yet peculiar atmosphere. A man comes home to his wife and announces that he met the prominent scholar, Treitle Groshkover, on the road home. It being cold outside, the man invited Groshkover to a warm meal. The wife’s face goes white; she heard through passing that Groshkover was dead, that he passed some three years ago. This must not be Groshkover, she insists; this must be an evil spirit in Groshkover’s body.

Not unlike their 2007 masterwork No Country for Old Men, the means to unlocking this film exists within the first scenes. Whereas Tommy Lee Jones’ narration gave way to the human despair and savagery that followed it, the prologue in A Serious Man tells a fable to help illustrate the purpose of the ensuing film: It recounts the tale of a Jewish couple in an old Eastern European village who argue about whether or not their noble guest, played by Fyvush Finkel, is a dybbuk (a Jewish specter). The scene appears in a smaller aspect ratio shaped for early cinema, the corners foggily suggesting a red iris that gives the scene a timeless, yet peculiar atmosphere. A man comes home to his wife and announces that he met the prominent scholar, Treitle Groshkover, on the road home. It being cold outside, the man invited Groshkover to a warm meal. The wife’s face goes white; she heard through passing that Groshkover was dead, that he passed some three years ago. This must not be Groshkover, she insists; this must be an evil spirit in Groshkover’s body.

When their guest comes to the door they politely invite him in. He looks normal enough but the wife remains suspicious. They offer him soup and he turns it down; the hour is too late for food. The wife takes this as proof of Groshkover’s ethereal form, since surely a ghoul would not eat. She accuses him of being a dybbuk, while her husband defends his own position: “I, of course, do not believe such things. I am a rational man.” Suddenly the wife stabs the supposed dybbuk in the chest to prove her point. Groshkover does not bleed at first, not until the wife points out that he is not bleeding, and then blood begins to seep from the wound. Groshkover laughs awkwardly and stands to leave the tense situation. The wife feels vindicated in her belief that this man was a dybbuk, while the husband believes his wife has stabbed an innocent man. Either the wife dispelled evil from her home and her husband is a fool for inviting it in, or the wife is a murderer. Which one of them is right? Groshkover disappears into the snowy night, never to enlighten our curiosity. But consider it a hint that the Coens credit Finkel’s role as “Dybbuk?” and not as Treitle Groshkover. The tale has severe implications on the rest of the film, and confounded viewers will do well to remember it in comparison to every scene that follows.

As the film proceeds, the Coens bring the audience just outside Minneapolis, Minnesota in the 1960s. Having grown up in the surroundings, the Coens avoid using the location to fuel nostalgia or sentimental remembrances of their childhood. As with all their films, A Serious Man explores a perfect unison between setting and story. Where better than the Jewish suburbia of St. Louis Park in 1967 could the filmmakers conceive an allegory rooted in the dangers of searching for meaning where there is none? The presentation is that of a plainly opaque film, haunting and perplexing, shot with a brooding sense of dread, almost like nightmarish horror. After all, what could be more horrific than realizing there are no real answers to life, only our suppositions? Or that the answers are just as enigmatic to the questions asked? Carter Burwell’s eerie music thumps and creeps, while the Coens attempt to lower their audience’s guard with the seemingly banal setting.

The protagonist makes his first appearance in an awkward state, disrobed at the doctor’s office, where he endures X-rays and receives a clean bill of health. Larry, played with upturned eyes and a furrowed brow by Michael Stuhlbarg, seems destined to be stepped on, humiliated, and ignored by his family and friends. His predicaments begin when his wife Judy (Sari Lennick) asks for a ritual divorce, which would make her free to remarry family friend Sy Ableman (Fred Melamed). His daughter wants a nose job and goes to friends’ houses to wash her hair, only because Larry’s indolent, gambling-addicted brother (Richard Kind), who may or may not be a mathematical genius, hogs the bathroom to drain the cyst on his neck. Larry’s detached, pot-smoking son telephones him while he meets with the divorce attorney (Adam Arkin), asking if Larry will come home to fix the antenna and clear the reception for F-Troop. On the roof after correcting the antenna, Larry looks about and spies his attractive neighbor sunbathing nude in her backyard; on the other side, the goy (non-Jewish) neighbor posts plans to inch over the property line with his new boat shed. Then Judy asks Larry to move into the Jolly Roger with his brother, at least while details of the divorce are worked out—as consolation, she insists that no bedroom “whoopsie-doopsie” is going on with Sy yet.

Larry’s work situation offers no reprieve, as his pending tenure review threatens to be sabotaged by an unknown party. A member of the tenure board alerts Larry to inflammatory letters they have received which denigrate him; the letters are anonymous, though probably written by Sy. The board member offers his reassurance, “I feel I should mention it, though it holds no bearing”—but that hardly comforts Larry. Meanwhile, a failing South Korean student, Clive Park (David Kang), asks Larry to change his grade to a passing one; when Larry refuses to budge, the boy leaves his office, and Larry finds an envelope filled with cash on his desk. A bribe? Larry cannot be sure, but he assumes so. In the midst of his office hullabaloo, his office phone rings nonstop with calls from someone from Columbia House trying to collect on a late bill for records Larry did not order. The stressors keep piling up, interrupting and stacking upon one another.

In Larry’s search for advice to explain why his luck has gone sour, a friend tells him that Jewish traditions and stories are what their people depend on to explain the questions of life, so Larry looks to rabbis for guidance. The First Rabbi, an inexperienced young trainee, directs him to gaze at the parking lot with wonder, and against that wonder, his problems will seem pithy. The Second Rabbi tells a seemingly pointless story of a goy with “help me” written on the inside of his teeth in Hebrew, an anecdote with a “We can’t know everything” message about a dentist searching for answers. And the Third Rabbi, the elder Marshak, is much too busy to bother with the likes of Larry. Ironically, when Larry later tries to calm Arthur, who breaks down in a fit of self-despair over the misfortunes in his own life, he tells his brother, “Sometimes you have to help yourself.” Larry is incapable of heeding his own counsel because he remains a “serious man,” a God-fearing man who believes in a divine system for all things. If there are misfortunes in his life, he believes there simply must be a reason to them—he never considers the possibility that Hashem, or God, or The Divine is just cruel.

Through it all, Larry has no last straw or breaking point, to the extent that he might be deemed a passive protagonist. He endures these events with visible strain, but he has too much faith to simply break down. When he complains, Larry does so only in the safety of confidentiality, with his rabbi or his attorney, and he never involves his family or friends. His struggle remains internal. With only a state of surprised disbelief does he question that his wife and Sy want him to move out into the Jolly Roger; he does not put his foot down in protest. He cannot believe his ears when Danny wants him to come home from the attorney’s office to fix the television antenna, and yet he leaves so his son can watch F-Troop. Larry might be considered passive for his lack of protest, but his conflict is not with an external source; rather, he searches for an answer from the elusive Hashem, who, of course, remains silent when Larry is looking for answers.

Through it all, Larry has no last straw or breaking point, to the extent that he might be deemed a passive protagonist. He endures these events with visible strain, but he has too much faith to simply break down. When he complains, Larry does so only in the safety of confidentiality, with his rabbi or his attorney, and he never involves his family or friends. His struggle remains internal. With only a state of surprised disbelief does he question that his wife and Sy want him to move out into the Jolly Roger; he does not put his foot down in protest. He cannot believe his ears when Danny wants him to come home from the attorney’s office to fix the television antenna, and yet he leaves so his son can watch F-Troop. Larry might be considered passive for his lack of protest, but his conflict is not with an external source; rather, he searches for an answer from the elusive Hashem, who, of course, remains silent when Larry is looking for answers.

The sole sustaining factor is the hope that Hashem desires to teach some lesson from Larry’s ongoing misfortune. Perhaps the ongoing suffering is merely a test of Larry’s faith in Hashem to determine how much he can undergo; when enough torment has been endured, the weight lifts. In the last scenes after Danny’s bar mitzvah, Larry’s problems seem to ease away. His friend on the tenure board drops a hint that Larry will be “pleased” with their decision, and things with Judith calm down when Sy dies in a car accident—at the same time that Larry was in a car accident no less, though he walked away unharmed. Maybe Larry’s misfortune has improved. In his office, he decides to solve the Clive problem himself by changing the grade to a passing one. Once he does this, the telephone rings. His doctor wants to discuss Larry’s X-rays, today, right now. A sense of dread fills Larry. Meanwhile, at Danny’s school, the class is ordered to the shelter during a tornado warning. Outside, as the teacher fumbles with the keys to the shelter, Danny calls to a classmate in order to finally pay him back owed money. But the boy does not turn to Danny at first; his eyes are locked on a tornado that approaches in the distance.

Larry’s existential dilemma serves up a parable intentionally void of answers, but rather filled with inquiry parallel to that in The Book of Job. True enough, both Job and Larry are pious, serious men plagued by the tortures of existence, forced to question and debate God’s intentions. In the ancient story, Satan insists that Job remains pious only because of his good fortune, which informs the ending of A Serious Man when, after enduring the film’s unrelenting series of trials, Larry gives in and finds himself destroyed for his sudden weakness. The story of A Serious Man may be a case of God testing Larry Gopnik’s resolve, seeing how much the unlucky Jewish man can tolerate before he cracks and changes a grade or does something else that would render him sanctimonious. If Larry had only accepted that God was testing him and pushed forward without questioning God’s intentions, then maybe Larry would have come out unscathed. Or maybe the story is just a bunch of things that happened, all seemingly meaningful, even profound, but in reality, from a realist point of view, just a series of coincidences. Who can know God’s intentions, or even if there is a God at all?

More than an allegory about faith in a god, A Serious Man questions certainty, extending the doubt from religious uncertainties to the questions in everyday life. The appearance of Schrödinger’s Cat theory early in the film suggests as much. A cat is placed in a box with a killing device; either the device will go off, or it will not. Because we cannot see inside the box, both are possibilities, therefore at any given moment the cat is alive or dead, or both at the same time. This 1935 thought experiment from the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger explains how, as Larry puts it, “We can’t ever really know what’s going on.” That type of thinking could be applied to any of the trials Larry faces throughout the film. He does not know anything, but he suspects. Every plot point presents a question. Did Judith really avoid “whoopsie-doopsie” with Sy, or was she just saying that so she would look better in the divorce? Larry does not witness Clive leave the money—did he actually present a bribe, or did Larry just make an assumption? Is Sy writing the defamatory letters to the tenure review board? What exactly is Arthur up to at night? Beyond illegal gambling, what of his ‘Mentaculous’ project, or the accusations of sodomy? Is Arthur a misunderstood genius or a pervert? The one answer to all of these questions is simply that Larry doesn’t know.

More than an allegory about faith in a god, A Serious Man questions certainty, extending the doubt from religious uncertainties to the questions in everyday life. The appearance of Schrödinger’s Cat theory early in the film suggests as much. A cat is placed in a box with a killing device; either the device will go off, or it will not. Because we cannot see inside the box, both are possibilities, therefore at any given moment the cat is alive or dead, or both at the same time. This 1935 thought experiment from the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger explains how, as Larry puts it, “We can’t ever really know what’s going on.” That type of thinking could be applied to any of the trials Larry faces throughout the film. He does not know anything, but he suspects. Every plot point presents a question. Did Judith really avoid “whoopsie-doopsie” with Sy, or was she just saying that so she would look better in the divorce? Larry does not witness Clive leave the money—did he actually present a bribe, or did Larry just make an assumption? Is Sy writing the defamatory letters to the tenure review board? What exactly is Arthur up to at night? Beyond illegal gambling, what of his ‘Mentaculous’ project, or the accusations of sodomy? Is Arthur a misunderstood genius or a pervert? The one answer to all of these questions is simply that Larry doesn’t know.

As intentionally anticlimactic and bewildering as the conclusion may be for some, the Coens have a long history of making audiences ponder the meaning behind their films. They also remain cautious about discussing what their films mean, which is part of their appeal for audiences engaged by a mystery. The end of Barton Fink makes us wonder what John Turturro’s psychotic neighbor kept in that box, whereas more recently, some felt baffled by No Country for Old Men’s ruminative last scene. Raising Arizona left Nicholas Cage peering into the uncertain future in his dreams. The Big Lebowski’s narrator loses his train of thought when explaining the purpose of his story. In The Man Who Wasn’t There, a UFO hovers above a noir hero on death row, its meaning elusive. In Burn After Reading, FBI headquarters shrugs off the film’s events as pointless, just a bunch of coincidences. Such examples go on and on. The joy in the Coens’ brand of filmmaking comes from their signature idiosyncrasies, their sense of distorted reality, and their ability to layer their storytelling. The Coens demand audience interpretation with their films; their films are post-modern, even surrealist in that sense.

When, in a dream, Sy repeatedly slams Larry’s head against the chalkboard where the aforementioned Uncertainty Principle is written, we can imagine the Coens speaking directly to those viewers who seek a tidy ending and balk when forced to dwell on cinema. The scene may be a direct reaction to audiences who loved No Country for Old Men, all except the ending. Regardless of the occasional unimaginative moviegoer, that the Coens require so much participation from viewers and yet remain both artistically and commercially successful presents a wonderful oddity within itself. But perhaps, as Sy suggests to Larry in his none-too-subtle way, audiences should simply accept that there are no answers offered in the film and move on. A more graceful explanation resides in the opening quote from Elie Wiesel’s book Rashi: “Receive with simplicity everything that happens to you.” By doing the opposite and dwelling on his problems, Larry slowly propels himself toward death. The Coens resolve that no matter how wearisome the film’s events may seem, these are just things that happen. A tremendously complicated, intelligent, and intriguing motion picture, and arguably the Coen brothers’ best, A Serious Man is curious as a narrative but wholly momentous as a parable, implanting in the viewer a prolonged sense of reflection, even its purpose is to prevent the audience from over-examining their lives.

Bibliography:

Baz Allen, William Rodney, ed. The Coen Brothers: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2006.

Bergan, Ronald. The Coen Brothers. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2000.

Palmer, R. Barton. Joel and Ethan Coen. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Rowell, Erica. The Brothers Grim: The Films of Ethan and Joel Coen. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2007.

Woods, Paul A., ed, Joel and Ethan Coen: Blood Siblings. London: Plexus, 2000.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review