The Definitives

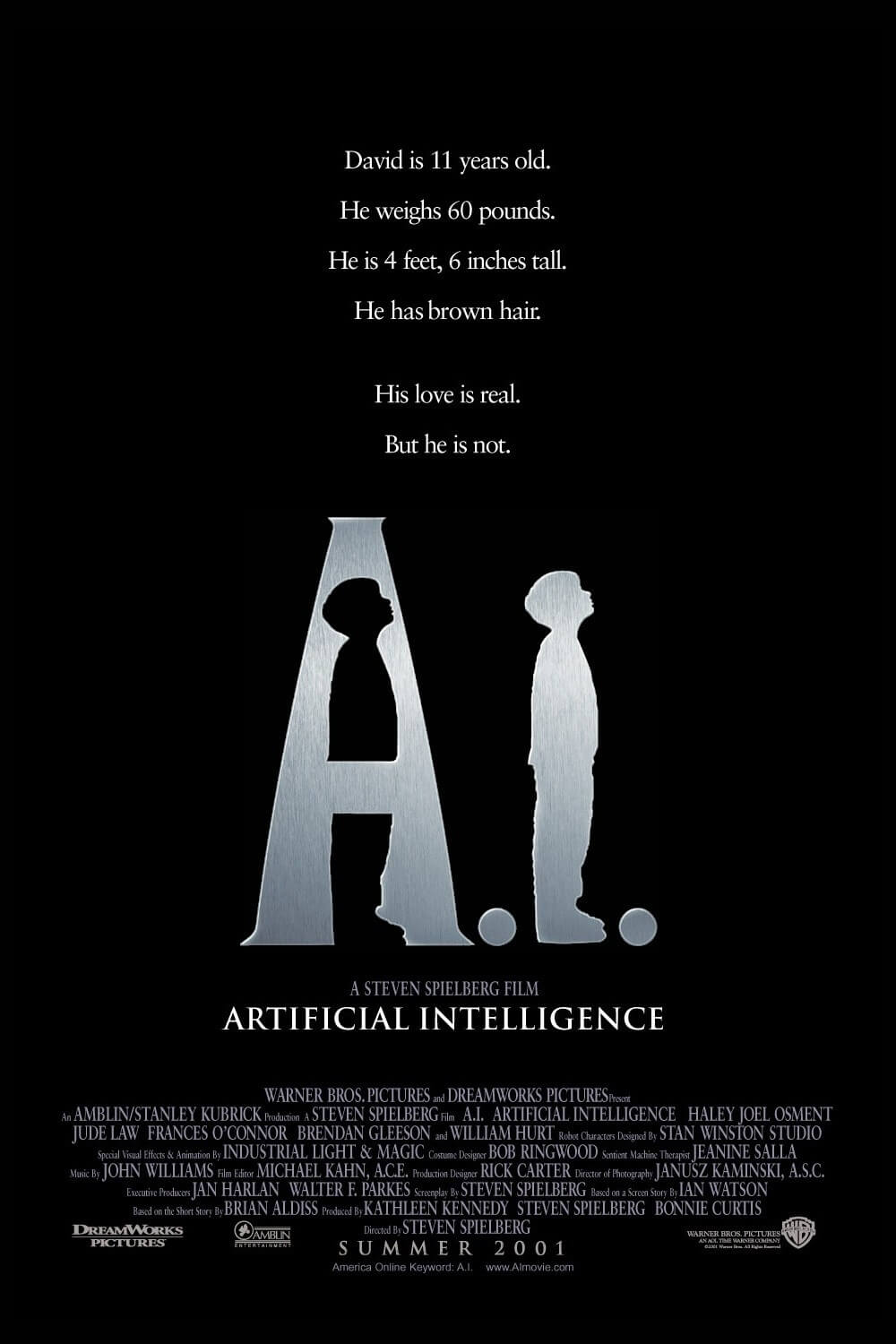

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Visionary and moving, A.I. Artificial Intelligence dares its audience to emotionally invest in an inhuman, robotic protagonist. Many could not, and today the film goes largely forgotten and unappreciated as an admirable, ambitious failure that overestimates its audience’s narrative commitment. Based on Supertoys Last All Summer Long by Brian Aldiss, the picture was developed by Stanley Kubrick for decades prior to his death and ultimately handed over to Steven Spielberg for completion. Upon its release in 2001, the film was plagued with discussions about which filmmaker, Kubrick or Spielberg, was responsible for which elements of the story. Never has a motion picture suffered so much from cineastes attempting to assign auteur signatures. All the magic onscreen was eclipsed through these ongoing discussions, leaving an ingenious film lost, waiting to be rediscovered. Much of the trouble results from expectations, and what we expect from “A Steven Spielberg Film” versus “A Stanley Kubrick Film.” We’ve made up our minds about what these filmmakers are capable of, and A.I. doesn’t seem to align with either sensibility, not entirely. On the whole, Spielberg was accused of sentimentalizing Kubrick’s often cerebral approach, whereas the late filmmaker’s prolonged research and development suggests he always intended a sentimental film, and he even implored Spielberg to direct early on. Revisiting the film brings a sense that what resulted from Kubrick’s development and Spielberg’s execution is a singular experience, unlike anything either filmmaker could have done on their own. It’s a film whose humanity is kept at a distance so audiences might question how to define it, challenging us through its narrative to approach humanity from a human-less perspective.

In the first scenes, Professor Hobby (William Hurt), head of leading robot or “mecha” manufacturer Cybertronics, proposes their newest model be a child capable of unconditional love. The first test unit is offered to a company employee, Henry Swinton (Sam Robards), and his wife Monica (Frances O’Connor), whose son, Martin (Jake Thomas), remains in suspended animation until a cure for his rare disease can be found. With the arrival of the eerily human-looking prototype, David (Haley Joel Osment), Monica’s initial aversion is overcome by her longing to be a mother. She resolves to imprint with David, forever assigning his unswerving love to her, his “mother”. As the film progresses, Osment’s wonderful performance, and therefore David, evolves from awkward robotic behavior to humanlike reactions as the mecha child develops. Much like Pinocchio, it takes time for David to find his bearings, and as he does, Monica’s love for David grows. But with a sudden cure found for Martin, David’s presence becomes redundant and problematic, and, out of motherly protection, Monica abandons her automaton child in the forest to prevent his destruction at Cybertronics. David assumes he can return once he becomes a real boy. Along with his own personal Jiminy Cricket, a robotic Supertoy Teddy (voiced by Jack Angel), David embarks on an odyssey into the unforgiving existence of unregistered robots. He learns from newfound friend Gigolo Joe (Jude Law), a mecha designed for companionship, that humans resent mechas for undermining humanity, and so unregistered mechas are hunted and despised. Figures like Lord Johnson-Johnson (Brendan Gleeson) conduct “Flesh Fairs” and destroy robots for entertainment, and David narrowly escapes becoming the main attraction when an audience is convinced he’s a real boy. To actually become real, however, David believes he must find the Blue Fairy, like the protagonist in his storybook The Adventures of Pinocchio.

David’s search for the Blue Fairy takes him through the neon-glowing sexual metropolis of Rouge City to a flooded Manhattan barely peeking out from the rising ocean. He follows carefully placed clues to find Professor Hobby among an inventory of David mechas. Hobby explains that David’s entire journey proved that his brand of artificial intelligence contains an irrefutable humanity by way of love and desire—his belief in something impossible and intangible like the Blue Fairy equates to a human dream, something never thought possible in a mecha. Although, David is told he can never be as real or unique as a human being. At this, David plunges himself into the ocean, where he comes upon the Blue Fairy statue at the underwater Coney Island. Trapped there, he repeats his wish to the Blue Fairy, asking her to make him a real boy, so that he might return to Monica and feel her love once more. He repeats the wish on and on, until the ocean freezes as two millennia pass. Evolved mechas have begun to carve evidence of an extinct human civilization from the ice. They find David frozen and thaw him, his robotic memory and experiences preserved. Through David’s comparatively basic programming, these highly developed mecha beings glimpse a rudimentary and fundamental form of humanity within David’s desire and love. David awakens, and before him, within a recreation of the Swinton home, he sees a mecha projection of the Blue Fairy. He imparts his wish to become human, but he’s told once more that he can never be a real boy. He can, however, experience one last day with Monica. The evolved mechas reconstruct her from a lock of hair, and David enjoys his final moments of affection with his mother. In essence, David has finally received his wish and become a real boy, as he represents the last lingering flicker of humanity in a world devoid of human life.

David’s search for the Blue Fairy takes him through the neon-glowing sexual metropolis of Rouge City to a flooded Manhattan barely peeking out from the rising ocean. He follows carefully placed clues to find Professor Hobby among an inventory of David mechas. Hobby explains that David’s entire journey proved that his brand of artificial intelligence contains an irrefutable humanity by way of love and desire—his belief in something impossible and intangible like the Blue Fairy equates to a human dream, something never thought possible in a mecha. Although, David is told he can never be as real or unique as a human being. At this, David plunges himself into the ocean, where he comes upon the Blue Fairy statue at the underwater Coney Island. Trapped there, he repeats his wish to the Blue Fairy, asking her to make him a real boy, so that he might return to Monica and feel her love once more. He repeats the wish on and on, until the ocean freezes as two millennia pass. Evolved mechas have begun to carve evidence of an extinct human civilization from the ice. They find David frozen and thaw him, his robotic memory and experiences preserved. Through David’s comparatively basic programming, these highly developed mecha beings glimpse a rudimentary and fundamental form of humanity within David’s desire and love. David awakens, and before him, within a recreation of the Swinton home, he sees a mecha projection of the Blue Fairy. He imparts his wish to become human, but he’s told once more that he can never be a real boy. He can, however, experience one last day with Monica. The evolved mechas reconstruct her from a lock of hair, and David enjoys his final moments of affection with his mother. In essence, David has finally received his wish and become a real boy, as he represents the last lingering flicker of humanity in a world devoid of human life.

On the initial screening, most viewers feel irresolute about the epilogue’s drastic shift into hopeful, distant future territory. Many critics, myself included, believed the film should have ended with David submerged in his vessel underwater, doomed to watch the Blue Fairy forevermore. Because after all, David could never be a real boy, could he? Reaching the Blue Fairy only to discover he would not become real would crush him and twist the fairy tale elements of the story into a nightmarish tragedy. And so, at the time of its release, this seemed the most practical conclusion for the film—at least, the most plausible ending in the film’s unfair world. What comes after David’s underwater imprisonment felt like pure fantasy in comparison to the events earlier. But the film’s ending upholds A.I.’s fairy tale intentions, granting a storybook happy ending, no matter how fantastic it may seem. Though the story has already displaced its audience by making the protagonist an automaton, the shift in the finale rearranges the state of the world in such a way that makes David the most human character onscreen. In those last moments, an audience can’t help but feel David’s delight in being with Monica, and thus identify with an artificial intelligence who has, in a way, become a real boy.

Still, detractors accused Spielberg of writing an outlandish conclusion wrought with sentimentality simply because, with Kubrick gone, the story was now his own. This perspective presupposes both that Kubrick wouldn’t have wanted a fairy tale conclusion and that Spielberg wrote the epilogue, but both assumptions would be incorrect. The deciding factor for Kubrick and Spielberg enthusiasts seems to be the question of which filmmaker conceived the epilogue. For many, it comes with shock and disbelief that Kubrick insisted upon it, and indeed fought many battles over its inclusion. In a 2002 interview with Joe Leydon to promote Minority Report, Spielberg argued “All the parts of A.I. that people assume were Stanley’s were mine. And all the parts of A.I. that people accuse me of sweetening and softening and sentimentalizing were all Stanley’s […] This was Stanley’s vision.”

Still, detractors accused Spielberg of writing an outlandish conclusion wrought with sentimentality simply because, with Kubrick gone, the story was now his own. This perspective presupposes both that Kubrick wouldn’t have wanted a fairy tale conclusion and that Spielberg wrote the epilogue, but both assumptions would be incorrect. The deciding factor for Kubrick and Spielberg enthusiasts seems to be the question of which filmmaker conceived the epilogue. For many, it comes with shock and disbelief that Kubrick insisted upon it, and indeed fought many battles over its inclusion. In a 2002 interview with Joe Leydon to promote Minority Report, Spielberg argued “All the parts of A.I. that people assume were Stanley’s were mine. And all the parts of A.I. that people accuse me of sweetening and softening and sentimentalizing were all Stanley’s […] This was Stanley’s vision.”

Kubrick’s long process of research for the project began in the early 1970s with an intention to drive his audiences toward a more positive viewpoint of artificial intelligences, and therein an openness toward future technologies. The reclusive filmmaker was aware that his usually distanced, philosophical approach might impede on the intended sentimentality of the story. And so, in 1985, he asked Spielberg, whose household name was synonymous with family-friendly science-fiction like E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, to join the production in a producer capacity. Over the years, the two directors shared hundreds of communiqués about the project, but Kubrick’s insistence that the production wait until industry technology could achieve his ambitions for the picture (this coming from the director of effects marvel 2001: A Space Odyssey) prevented any forward progress.

Kubrick initially hired Adliss to write a film treatment of his short story, while a number of writers including Bob Shaw, Ian Watson, and Sara Maitland helped shape the story in their respective drafts over the years. Watson’s 90-page novelette-style treatment fleshed out many of the final details, whereas Maitland helped imbue a fairy tale structure. Maitland lost many arguments with Kubrick about the final coda, believing it unnaturally dreamlike compared to the grim future realities present in the events preceding, but Kubrick demanded the final sequence remain in the script. Nevertheless, the then-modern special FX could not yet realize the future world Kubrick had visualized for the film. His ideas involved Manhattan submerged by waters from melted polar ice caps, an elaborate metropolis, and effects that would render the central Pinocchio character through robotics or advanced makeup techniques. Indeed, Kubrick referred to the project as “Pinocchio” and cited Italian author Carlo Collodi’s storybook The Adventures of Pinocchio as his primary source of inspiration.

The project was altogether shelved until 1993, when Kubrick and millions of moviegoers witnessed the incredible effects in Jurassic Park bring dinosaurs back to life. Kubrick immediately hired that film’s visual effects supervisors Dennis Muren and Ned Gorman to begin work on his “Pinocchio” film and develop digital animations based on concept artist Chris Baker’s designs. But his dissatisfaction with their preliminary work, and his increasing doubts that he could direct the material, incited him to hand the project to Spielberg to direct. Regardless, Spielberg passed and convinced Kubrick to remain as director, though any progress was postponed by his obligations to Eyes Wide Shut, a notoriously lengthy production that would last from 1997 until Kubrick’s death in 1999. With his death, the Kubrick estate convinced Spielberg to proceed with the “Pinocchio” story and, taking pieces from Kubrick’s own drafts, Spielberg completed his first original screenplay since Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

The project was altogether shelved until 1993, when Kubrick and millions of moviegoers witnessed the incredible effects in Jurassic Park bring dinosaurs back to life. Kubrick immediately hired that film’s visual effects supervisors Dennis Muren and Ned Gorman to begin work on his “Pinocchio” film and develop digital animations based on concept artist Chris Baker’s designs. But his dissatisfaction with their preliminary work, and his increasing doubts that he could direct the material, incited him to hand the project to Spielberg to direct. Regardless, Spielberg passed and convinced Kubrick to remain as director, though any progress was postponed by his obligations to Eyes Wide Shut, a notoriously lengthy production that would last from 1997 until Kubrick’s death in 1999. With his death, the Kubrick estate convinced Spielberg to proceed with the “Pinocchio” story and, taking pieces from Kubrick’s own drafts, Spielberg completed his first original screenplay since Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Spielberg set aside his usual commercial mindset to observe Kubrick’s compulsive call for secrecy. He prohibited press from the set and signed his actors to confidentiality agreements. Aside from some exteriors in Oregon, the production filmed on secure sound stages. Promotional materials were kept to a minimum to ensure a mature demographic: an innovative online “alternate reality game” called The Beast created awareness about the film’s future world, whereas the sole toy released was a talking, gleefully grumpy Supertoy Teddy from Hasbro. Even with this exception, the message was clear: Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence was not a family film. As a result, the summer release just missed earning back its $90 million budget at the U.S. box office; international audiences were more responsive, adding $150 million to the worldwide total. Critics reacted with either harsh disdain or confused admiration. Mincing no words, Brian Aldiss remarked, “It’s crap.” Roger Ebert was more generous when, in his fond but dissatisfied review, he wrote the film is “audacious, technically masterful, challenging, sometimes moving, ceaselessly watchable.” By and large, audiences failed to find the intended humanity in the story.

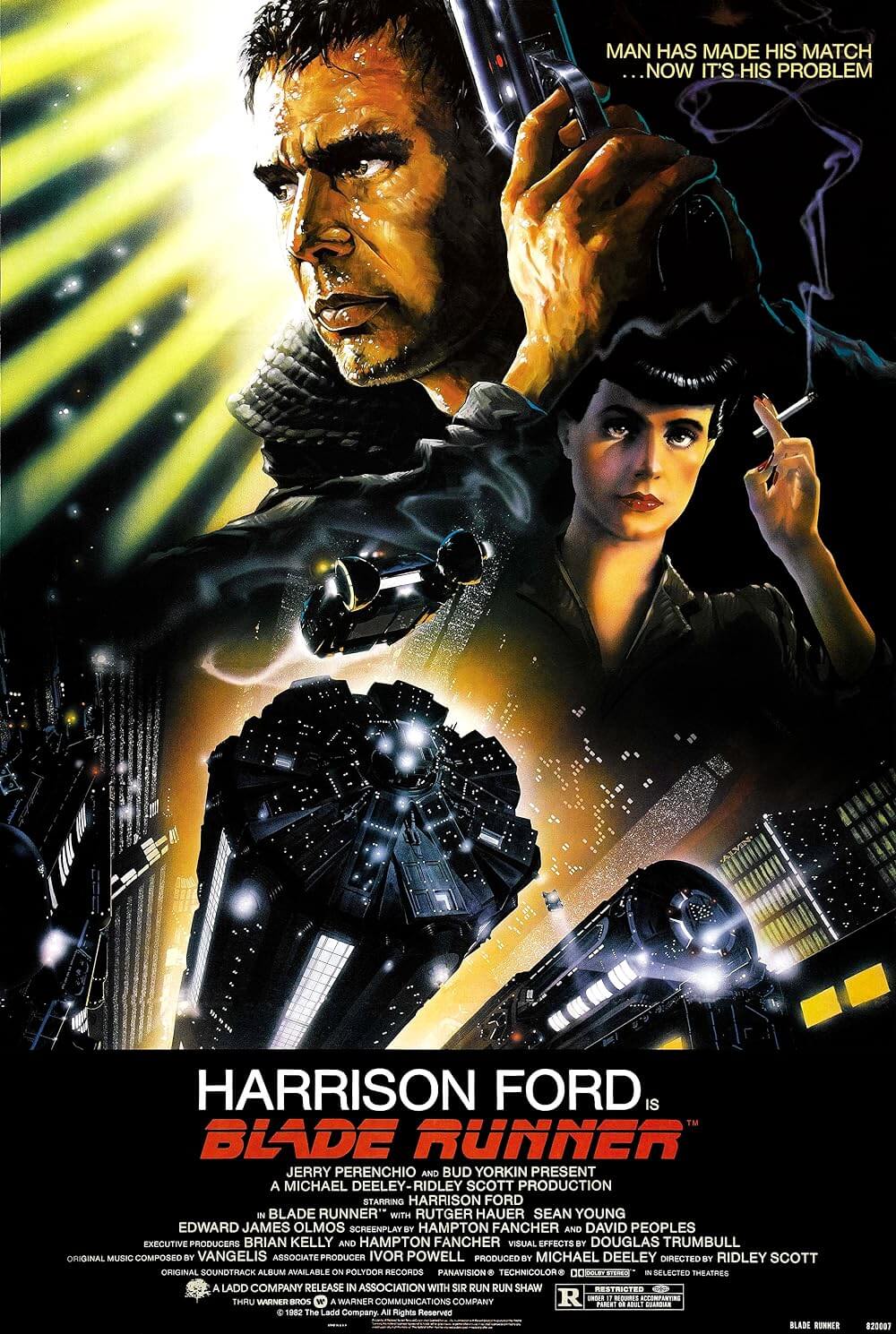

Unanimous among the responses were awestruck reactions to the technical marvels and inconceivable effects in the film. A.I. is simply gorgeous to behold—a science-fiction world to rival Blade Runner or even Spielberg’s next film, Minority Report. Kubrick’s instinct to wait until the industry’s technology could appropriately depict his vision was correct. Not without an innovative combination of the most state-of-the-art green screen computer animators, makeup artists, miniature builders, and mechanical effects could the complicated, multi-layered shots in Rogue City or the Flesh Fair come to life. Working with Stan Winston’s studio for makeup and robot effects and Industrial Light & Magic for the larger-scope visuals, Spielberg’s production amassed a then-unprecedented level of technical ingenuity. Winston himself claimed it was the most ambitious film on which he had ever worked (a bold statement coming from the effects man behind Aliens and The Terminator). At the following year’s Academy Award ceremony, A.I.’s effects were nominated along with the periodically haunting score by John Williams, one of his best. Curiously, the flat-out incredible and nuanced performances by Law and Osment were overlooked, as was the contrasting sheen and atmosphere by Spielberg’s longtime collaborator, cinematographer Janusz Kaminski.

Unanimous among the responses were awestruck reactions to the technical marvels and inconceivable effects in the film. A.I. is simply gorgeous to behold—a science-fiction world to rival Blade Runner or even Spielberg’s next film, Minority Report. Kubrick’s instinct to wait until the industry’s technology could appropriately depict his vision was correct. Not without an innovative combination of the most state-of-the-art green screen computer animators, makeup artists, miniature builders, and mechanical effects could the complicated, multi-layered shots in Rogue City or the Flesh Fair come to life. Working with Stan Winston’s studio for makeup and robot effects and Industrial Light & Magic for the larger-scope visuals, Spielberg’s production amassed a then-unprecedented level of technical ingenuity. Winston himself claimed it was the most ambitious film on which he had ever worked (a bold statement coming from the effects man behind Aliens and The Terminator). At the following year’s Academy Award ceremony, A.I.’s effects were nominated along with the periodically haunting score by John Williams, one of his best. Curiously, the flat-out incredible and nuanced performances by Law and Osment were overlooked, as was the contrasting sheen and atmosphere by Spielberg’s longtime collaborator, cinematographer Janusz Kaminski.

In the decade since its release, cineaste affections for the film have grown. A second or third viewing seems to instill the finale’s implications throughout the entirety, allowing viewers who revisit the film to recognize understated hints at David’s humanity early on, and then carry them through until the end. That so many could not at first find David’s humanity may be the film’s crucial flaw, or it may be the film’s resounding challenge that unsympathetic audiences ultimately failed. If, in the end, evolved robots have developed enough emotion to take David’s desires into consideration, then David himself represents a simplified version of their mecha humanity: a being made in the image of humanity to feel pure love and boundless devotion to his mother—what amounts to a real boy in a world of evolved mechas. A.I. recognizes that we’re all little more than complicated machines searching desperately for love. Though Kubrick’s films are often accused of being detached, films like Paths of Glory and Eyes Wide Shut demonstrate the work of a humanist’s profound understanding of people, whereas others such as A Clockwork Orange and Dr. Strangelove reveal our most severe flaws through cold cynicism. Overall, Spielberg’s films dwell on more optimistic stories of human potential, but never completely shy away from our deepest lows. Despite outward appearances, how could anyone consider Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, or Amistad blindly optimistic pictures, as each showcases a rare moment of human dignity within overwhelming instances of historical atrocity?

In the same interview with Joe Leydon, Spielberg commented, “People pretend to think they know Stanley Kubrick, and think they know me, when most of them don’t know either of us.” To this extent, any discussion of which director should be attributed to this or that moment in the film becomes meaningless, as Spielberg and Kubrick found a story that aligns with both filmmakers’ most optimistic and cynical views on human nature. With A.I., Kubrick had hoped the extent of human empathy would transcend the presence of human beings onscreen through the audience’s ability to recognize human emotion within an artificial lifeform, and Spielberg executes that challenge with matchless visuals and narrative daring, creating a convincing futureworld of artificial lifeforms and more than one incredible, unforgettable metropolis. The initial reactions vindicated Kubrick’s doubts toward humanity, whereas the film’s lasting effect shows a glimmer of hope. Upon revisiting the film, the wonders beyond its technical genius emerge to reveal a distinctive science-fiction storybook, one whose challenging narrative contains significant rewards for an audience with more evolved insights on humanity.

In the same interview with Joe Leydon, Spielberg commented, “People pretend to think they know Stanley Kubrick, and think they know me, when most of them don’t know either of us.” To this extent, any discussion of which director should be attributed to this or that moment in the film becomes meaningless, as Spielberg and Kubrick found a story that aligns with both filmmakers’ most optimistic and cynical views on human nature. With A.I., Kubrick had hoped the extent of human empathy would transcend the presence of human beings onscreen through the audience’s ability to recognize human emotion within an artificial lifeform, and Spielberg executes that challenge with matchless visuals and narrative daring, creating a convincing futureworld of artificial lifeforms and more than one incredible, unforgettable metropolis. The initial reactions vindicated Kubrick’s doubts toward humanity, whereas the film’s lasting effect shows a glimmer of hope. Upon revisiting the film, the wonders beyond its technical genius emerge to reveal a distinctive science-fiction storybook, one whose challenging narrative contains significant rewards for an audience with more evolved insights on humanity.

Bibliography:

Friedman, Lester D. Citizen Spielberg. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

McBride, Joseph. Steven Spielberg (Third Edition). London. Faber and Faber, 2012.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review