The Definitives

A History of Violence

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In A History of Violence, David Cronenberg peels back the skin of civilization to reveal an infection underneath. The story, about an average man with a dark secret, serves the director’s grim commentary on how the social constructs of family and community, professed to be civilized, conceal the intrinsic barbarity of human beings. At first glance, the material doesn’t resemble what cinéastes would call Cronenbergian. The invasive and gory violence often associated with the Canadian auteur, the so-called Baron of Blood or King of Venereal Horror, has been disguised by the everyday in his 2005 film. His cinematic violence is no longer situated in some science-gone-wrong conceit (The Fly, 1986), freakish externalization of internal anxiety (The Brood, 1979), psychosexual hallucination brought about by television or drugs (Videodrome, 1983; Naked Lunch, 1991), or deviant subculture of twisted metal and sex (Crash, 1996). Instead, Cronenberg explores how violence is written into our DNA, even if the surface suggests otherwise. He uses A History of Violence’s outwardly mundane characters, restrained aesthetics, and familiar scenery to present a narrative treatise on how violence plays a vital role not just in the film’s central family, but in an entire species and its various social interactions. However unassuming it appears, A History of Violence is Cronenberg’s most human and grounded film about his career-long theme of the internal becoming external.

On the surface, A History of Violence resembles many other films about violence hiding just beneath the pretense of civilization. For instance, David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) begins in a saccharine version of Anytown, USA, only to reveal an underworld of drugs, kidnapping, sadomasochistic sex, and psychopathic violence upon closer inspection. Both Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring (1960) and Wes Craven’s 1972 remake The Last House on the Left consider seemingly civilized parents who respond with animalistic violence when faced with the people who raped and murdered their daughters. Among the most controversial examples is Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), about a mathemetician whose intellectualism gives way to savage violence to protect his home from a group of workmen who have raped his wife. In fact, much of Peckinpah’s work attempts to portray humanity’s default status as violent beasts. But in many of these examples—in particular, the noted films by Craven and Peckinpah—the depiction of grisly violence threatens to outweigh the theme. However, Cronenberg’s film approaches the subject by focusing on how violence impacts his characters’ lives in a larger discussion about violence and civilization.

Filmmakers interested in the root of humanity’s violence often identify civilization as a social conceit that ignores—even suppresses—humanity’s inherent drives. In The Philosophy of Civilization, theorist Albert Schweitzer argues that a nonviolent and ethical “reverence for life” represents “the real essential nature of civilization.” Thus violence goes against the very concept of civilization. French philosopher Étienne Balibar agrees that political and social structures equate “antiviolence” with civilization’s goals, including the “possibility for the ‘survival’ or the ‘rebirth’ of active politics in moments of existential crisis,” as opposed to violent action as a method of problem-solving. Civilization has all sorts of definitions related to relationships, behaviors, and human interactions; in relation to violence, though, it allows only for non-violence. Cronenberg’s assertion in the film that humanity and violence are inextricable rethinks civilization as either entirely nonexistent today according to how these philosophers define “civilization,” or, alternatively, Cronenberg posits that these philosophers are wrong and violence remains a denied characteristic and formative component of civilization. If the latter is true, nonviolence and idealized civilization prove more aspirational as opposed to an achievable objective.

Filmmakers interested in the root of humanity’s violence often identify civilization as a social conceit that ignores—even suppresses—humanity’s inherent drives. In The Philosophy of Civilization, theorist Albert Schweitzer argues that a nonviolent and ethical “reverence for life” represents “the real essential nature of civilization.” Thus violence goes against the very concept of civilization. French philosopher Étienne Balibar agrees that political and social structures equate “antiviolence” with civilization’s goals, including the “possibility for the ‘survival’ or the ‘rebirth’ of active politics in moments of existential crisis,” as opposed to violent action as a method of problem-solving. Civilization has all sorts of definitions related to relationships, behaviors, and human interactions; in relation to violence, though, it allows only for non-violence. Cronenberg’s assertion in the film that humanity and violence are inextricable rethinks civilization as either entirely nonexistent today according to how these philosophers define “civilization,” or, alternatively, Cronenberg posits that these philosophers are wrong and violence remains a denied characteristic and formative component of civilization. If the latter is true, nonviolence and idealized civilization prove more aspirational as opposed to an achievable objective.

A History of Violence opens with an unbroken four-minute shot and introduces a world inhabited by unthinkably violent characters. Looking on tableau-style from outside a motel, we see two men, Billy (Greg Bryk) and Leland (Stephen McHattie), groggily emerging from their room and continuing their journey eastward. Accordingly, the camera follows their slow, sleepy progress, moving left to right in an easterly direction. Leland walks ahead to check them out of the motel, while Billy inches their stolen car forward. For those versed in Cronenberg’s cinema, the opening is unlike any other in his oeuvre to this point. It’s stark, eerily quiet, and far removed from the director’s usual title sequences that employ overlapping images set against Howard Shore’s reverberating music. In the time it takes Billy to bring the car up to the front office, Leland emerges, and they bicker about who will drive and who will gather water for their ride. Losing the argument, Billy takes their jug and heads inside the office. The extended shot ends, but inside, the next shot reveals that Leland has left a bloody mess of the clerk and maid’s bodies. Unfazed by the familiar sight of death, Billy moves through the office, leisurely exploring the cooler amid Leland’s two victims. Nearby, he hears a young girl whimpering; she has overheard the murder. Billy shushes her in a feigned comforting gesture as if to say, It’s going to be all right. Then he shoots her at point-blank range.

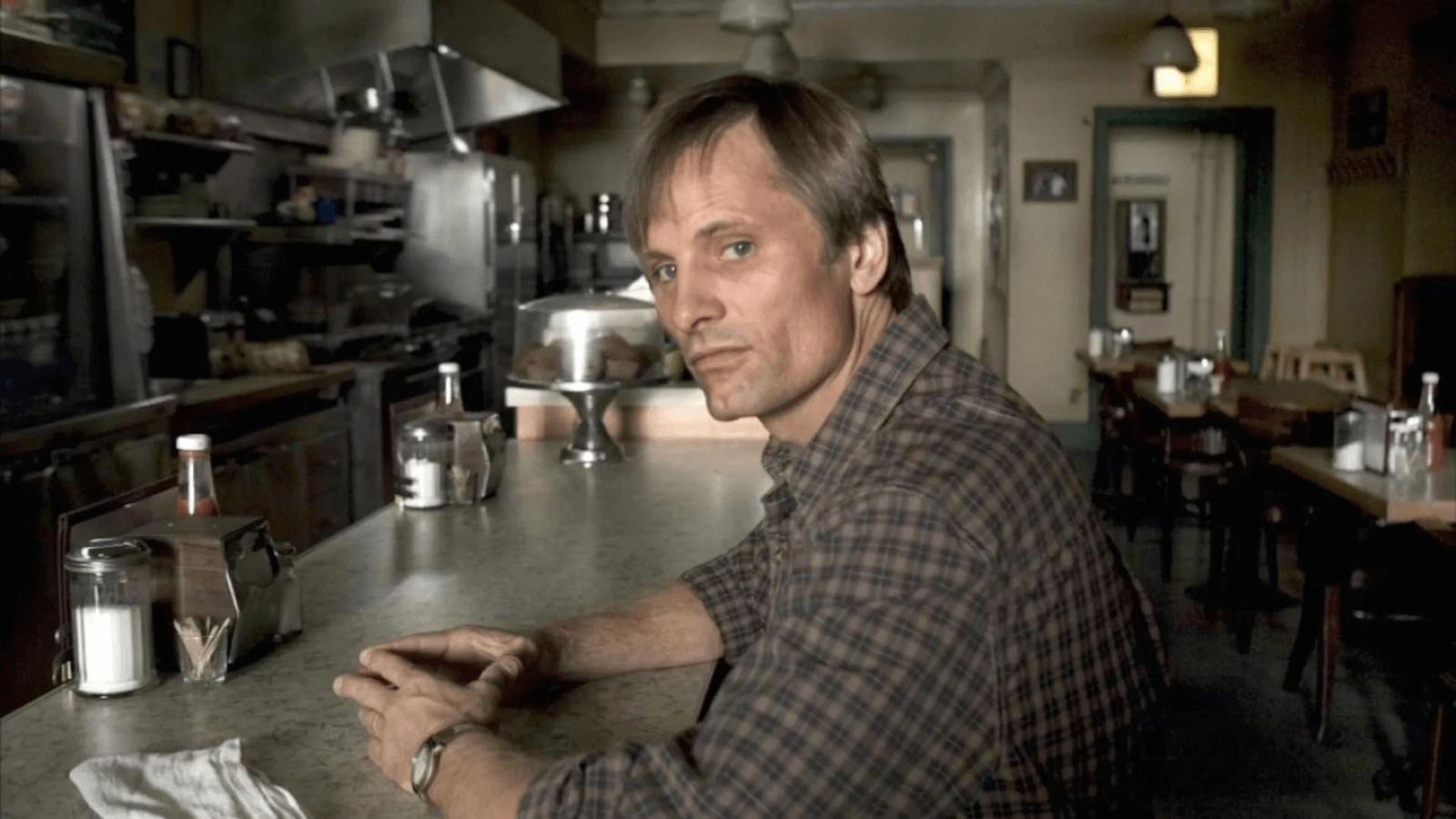

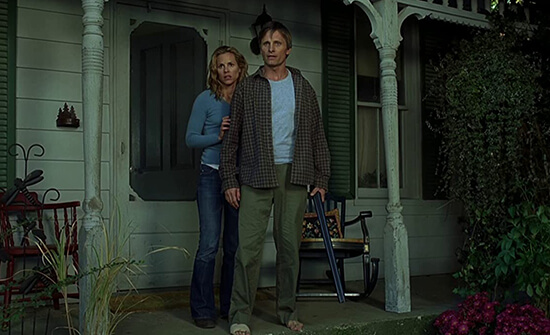

A bridging shot takes us to Millbrook, Indiana, in the home of the Stalls, where another young girl screams in her bedroom. Sarah Stall (Heidi Hayes) has had a nightmare, and her father, Tom (Viggo Mortensen), arrives to comfort her. A moment later, her teenage brother Jack (Ashton Holmes) joins them. After another moment, her mother, Edie (Maria Bello), completes the family scene, and assures Sarah that “There’s no such thing as monsters.” The Stalls live in an idyllic country house. They eat their breakfasts and dinners together, kiss each other hello and goodbye, and talk about their days. Jack frets about the upcoming baseball game, where he inevitably catches the winning out. Tom runs a local diner and fusses over his pickup truck that won’t start. Edie works as a real estate agent. Their lives might seem provincial, except for Cronenberg’s characteristic interest in their sexuality. He shows that Tom and Edie’s marriage still has life in the bedroom. Although their romance has been sublimated for their roles as responsible parents and heads of the family, Edie concocts a plan to “fix” how they never got to be teenagers together. One night, she performs a naughty cheerleader routine for Tom when the kids are away. Afterward, they lie awake talking about how they fell in love. “I’m the luckiest son of a bitch alive,” Tom reflects. “You are the best man I’ve ever known. There’s no luck involved,” Edie responds. Based on appearances, the Stalls couldn’t be more perfect, nor could their slice of Anytown, USA, appear more civilized.

But coming after the first sequence, a sense of dread lingers beneath this idyllic portrait of the Stall family. Any moviegoer knows these two juxtaposed groups of people will collide, and that’s a frightening notion. And sure enough, the killers from the first scene arrive at Tom’s diner at closing time one night, demanding to be served. The comforting down-home scene inside the diner—complete with a young couple sharing a milkshake—heightens our dread over Billy and Leland’s sudden appearance. A few beats later, the killers draw their weapons, intending to rob and murder everyone inside. But Tom responds with swift and decisive, almost superhuman action, disarming and killing Leland with a gunshot to the face before shooting Billy in the chest. Although Tom takes a knife to the foot, he saves the day. In the aftermath, the press coverage calling him a local hero brings the attention of Carl Fogarty (Ed Harris), an Irish mobster from Philadelphia who appears in Millbrook to confront Tom, who Fogarty claims is named “Joey.” Although Tom initially denies this, we learn later that, years ago, almost in another life, Tom went by Joey Cusack and killed mercilessly for his mobster brother, Richie (William Hurt). Joey broke the rules by attacking a made man, Fogarty, and removing his eye with barbed wire. Then Joey disappeared and became Tom. His recent appearance on the news forces Tom to confront his former self, represented not only by Joey’s enemies but also by the reality of his past life, which his wife and children learn about for the first time.

But coming after the first sequence, a sense of dread lingers beneath this idyllic portrait of the Stall family. Any moviegoer knows these two juxtaposed groups of people will collide, and that’s a frightening notion. And sure enough, the killers from the first scene arrive at Tom’s diner at closing time one night, demanding to be served. The comforting down-home scene inside the diner—complete with a young couple sharing a milkshake—heightens our dread over Billy and Leland’s sudden appearance. A few beats later, the killers draw their weapons, intending to rob and murder everyone inside. But Tom responds with swift and decisive, almost superhuman action, disarming and killing Leland with a gunshot to the face before shooting Billy in the chest. Although Tom takes a knife to the foot, he saves the day. In the aftermath, the press coverage calling him a local hero brings the attention of Carl Fogarty (Ed Harris), an Irish mobster from Philadelphia who appears in Millbrook to confront Tom, who Fogarty claims is named “Joey.” Although Tom initially denies this, we learn later that, years ago, almost in another life, Tom went by Joey Cusack and killed mercilessly for his mobster brother, Richie (William Hurt). Joey broke the rules by attacking a made man, Fogarty, and removing his eye with barbed wire. Then Joey disappeared and became Tom. His recent appearance on the news forces Tom to confront his former self, represented not only by Joey’s enemies but also by the reality of his past life, which his wife and children learn about for the first time.

Citing a conversation with Cronenberg, Roger Ebert references three possible interpretations for the title in his review: “It refers (1) to a suspect with a long history of violence; (2) to the historical use of violence as a means of settling disputes, and (3) to the innate violence of Darwinian evolution, in which better-adapted organisms replace those less able to cope.” In the former case, the viewer watches how a single individual, Tom Stall, deals with his past actions as a violent man—how they remain part of him, no matter how deep he buries them or conceals them from his family and community. This interpretation points to a single person’s history of violence, in the same manner a psychological profile might reference behavioral patterns. In the second interpretation, the film can be seen as a study of people using violence as a method of winning arguments, resolving conflict, and silencing dissent in a range of conflicts from schoolyard scuffles to world wars, implying that humanity has a history of violence. The same can be said of the third interpretation, which presents the film as an investigation into how the strongest of a species have a scientifically observed history of violence to survive in Nature. Tom becomes, then, a symbol of Nature’s sublime violence and continued evolution, demonstrated by a myriad of species that unsympathetically dominate the weak. “I think Cronenberg is most interested in the third,” wrote Ebert.

Although each of these interpretations, along with their micro or macro implications on the title, could make A History of Violence an intriguing text worthy of analysis, consider another alternative: that Cronenberg deconstructs how humanity and violence remain interlinked, but not just as a means of problem-solving or survival. Rather, violence shapes humanity through a vast network of social and cultural concerns. It’s not merely Darwinian in the sense that violence selects the fittest to survive. People have established their social existence around violence, its many horrors and pleasures, regardless of the associated morality. Violence remains at the core of how human beings relate to one another—yes, as a method of obtaining resolution or defeating the competition, but violence also has a role in family hierarchies, power struggles, gender dynamics, and sexuality. The film’s scope reaches beyond the individual and ideological to reveal the antagonistic relationship between so-called human civilization and our more primal natures as violent beasts. By exploring how violence emerges from Tom, and then from Edie and Jack, Cronenberg tears down a socially constructed façade—in this specific case, the myth of the American Dream and nuclear family—to reveal the fundamental violence operating beneath peaceful civilization.

A History of Violence was also the second film in a row, after 2002’s Spider, to deviate from Cronenberg’s genre-centric obsession with body horror. In a sense, Cronenberg’s films have always been about exploring internal, Lacanian hang-ups that manifest themselves in physical ways. Usually, these manifestations appear in a grotesque form. In The Brood, for instance, internal trauma becomes disturbingly physical when a radical form of therapy causes a woman to produce birth sacks that contain monstrous, murderous offspring. In The Fly, a scientist’s motion sickness in cars prompts him to invent a teleporter, but his invention goes awry when he accidentally splices his DNA with that of a housefly, gradually turning him into a monster. But Spider began a series of Cronenberg films in the 2000s and 2010s that resisted fantastical horror and dealt with relatively grounded subject matter—that nonetheless harbored the same obsessions with the mind-body dichotomy. Among all of the director’s work, A History of Violence is also the most commercial, even mainstream, despite the Canadian outsider’s usual independence. “I’ve been waiting for years to sell out,” Cronenberg joked at the film’s Cannes debut, “it’s just that nobody offered me anything before now.” To be sure, the film had a sizable budget for a Cronenberg production, $32 million, and at the time, became his second-most profitable film after The Fly.

A History of Violence was also the second film in a row, after 2002’s Spider, to deviate from Cronenberg’s genre-centric obsession with body horror. In a sense, Cronenberg’s films have always been about exploring internal, Lacanian hang-ups that manifest themselves in physical ways. Usually, these manifestations appear in a grotesque form. In The Brood, for instance, internal trauma becomes disturbingly physical when a radical form of therapy causes a woman to produce birth sacks that contain monstrous, murderous offspring. In The Fly, a scientist’s motion sickness in cars prompts him to invent a teleporter, but his invention goes awry when he accidentally splices his DNA with that of a housefly, gradually turning him into a monster. But Spider began a series of Cronenberg films in the 2000s and 2010s that resisted fantastical horror and dealt with relatively grounded subject matter—that nonetheless harbored the same obsessions with the mind-body dichotomy. Among all of the director’s work, A History of Violence is also the most commercial, even mainstream, despite the Canadian outsider’s usual independence. “I’ve been waiting for years to sell out,” Cronenberg joked at the film’s Cannes debut, “it’s just that nobody offered me anything before now.” To be sure, the film had a sizable budget for a Cronenberg production, $32 million, and at the time, became his second-most profitable film after The Fly.

A History of Violence explores violence as an external manifestation of an internalized identity, much in the same way Cronenberg’s horror-centric films use grotesque imagery as symbolic expressions of psychological conditions. Josh Olson’s efficient and shrewdly observed script—Oscar-nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay—derives from a 1997 graphic novel of the same name, written by John Wagner, with illustrations by Vince Locke. Despite its first-glance appearance as a standard Hollywood production, its origins give the film the unlikely distinction as an unconventional comic-book-to-film adaptation. The story structure, too, echoes conventional motifs in the Western genre, such as Anthony Mann’s Man of the West (1958) and Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992)—both about former gunslingers who, after years of settling down in a civilized home, must once again take up arms and resolve a conflict with violence. However, Olson and Cronenberg offer a wider understanding of violence beyond the traditional Wild West picture or gangster movie. Cronenberg once said his earlier horror films sought to understand the world “from the disease’s point of view,” and A History of Violence attempts something similar, albeit to assess the many ways that humankind is hardwired to be violent. By the film’s conclusion, Cronenberg demonstrates the many potential effects of violence: how it solves problems; makes you a hero; gains you admiration from your community; feels good after a victory; inspires imitation, especially where heroes and victories are concerned; results in authority and dominance; turns you on (whether you like it or not); links us to the past; traumatizes you, physically and psychologically; and after it’s over, requires healing.

Many of these causes and effects transpire in A History of Violence in relation to the Stalls, signaling Cronenberg’s interest in the family unit as a model example of civilization. Although the lessons and consequences of violence remain at the film’s center, much of the 96-minute runtime deals with how violence disrupts the otherwise serene Stall family household. Scholar Ernest Mathijs writes that A History of Violence and Cronenberg’s next film, Eastern Promises (2007), another drama starring Viggo Mortensen about a father figure who defends his (makeshift) family from criminal opposition, represents a shift toward an interest in the “habits, rituals and traditions that help sustain family functions.” Mathijs argues that Cronenberg, in his sixties at the time of making these films, had started to reflect on his place at the head of a filmmaking family, including three adult children, all filmmakers. Unlike Cronenberg’s earlier films, A History of Violence considers the family unit’s health as central to the narrative, whereas, say, the family in The Brood never had much chance of restoration. The film also concerns the Stall family’s place in the Millbrook community, where Sheriff Sam (Peter MacNeill) insists, “We take care of our own,” and the town never appears less than an Arcadian. Millbrook sees Tom as an “American hero,” according to one broadcaster. When he emerges from the hospital after his initial encounter in the diner, a small crowd showers him with applause and shouts, “Way to go, Tom!” After the diner incident, and the subsequent evidence that Tom isn’t who he appears to be, the Stalls attempt to contain and keep their relationship with violence a secret, preserving the sanctity of their nuclear family and outward appearance of civilization.

Meanwhile, violence infects the Stalls like a disease, starting with Jack, Tom’s adolescent son who’s bullied at school by prototypical jock Bobby (Kyle Schmid). After the incident at the diner, Jack sees how the community celebrates his father as a hero. The boy also admires how, when his father fears that Fogarty may be targeting Edie at home, Tom runs miles with an injured foot to the rescue. As a result, Jack learns a lesson about the positive outcomes of violence—that violence can be used in the service of good versus evil, hero versus villain—and applies that to his life. Even though Jack successfully uses wit to deflate a locker-room confrontation with Bobby earlier in the film, when confronted after his father’s incident at the diner, he doesn’t just defend himself but preemptively strikes, issuing a severe beating that earns him a suspension. Some critics read Cronenberg’s critique to be about America’s violent culture, noting the distinctly American flavor of the jock-nerd conflict, complete with Bobby’s macho letter jacket contrasted by Jack’s smarts and bumbling physicality as evidence. But bullying isn’t an inborn American characteristic; it’s pervasive across all cultures. Even so, at home, Tom rebukes his son’s behavior: “In this family, we do not solve our problems by hitting people.” Jack fires back, “No, in this family, we shoot them.” Tom responds by slapping Jack across the face. Whereas earlier scenes showed the Stalls communicating over breakfast verbally, violence now becomes the method of instruction and communication between father and son.

Meanwhile, violence infects the Stalls like a disease, starting with Jack, Tom’s adolescent son who’s bullied at school by prototypical jock Bobby (Kyle Schmid). After the incident at the diner, Jack sees how the community celebrates his father as a hero. The boy also admires how, when his father fears that Fogarty may be targeting Edie at home, Tom runs miles with an injured foot to the rescue. As a result, Jack learns a lesson about the positive outcomes of violence—that violence can be used in the service of good versus evil, hero versus villain—and applies that to his life. Even though Jack successfully uses wit to deflate a locker-room confrontation with Bobby earlier in the film, when confronted after his father’s incident at the diner, he doesn’t just defend himself but preemptively strikes, issuing a severe beating that earns him a suspension. Some critics read Cronenberg’s critique to be about America’s violent culture, noting the distinctly American flavor of the jock-nerd conflict, complete with Bobby’s macho letter jacket contrasted by Jack’s smarts and bumbling physicality as evidence. But bullying isn’t an inborn American characteristic; it’s pervasive across all cultures. Even so, at home, Tom rebukes his son’s behavior: “In this family, we do not solve our problems by hitting people.” Jack fires back, “No, in this family, we shoot them.” Tom responds by slapping Jack across the face. Whereas earlier scenes showed the Stalls communicating over breakfast verbally, violence now becomes the method of instruction and communication between father and son.

Then, Jack runs out of the house to cool down, only to be taken by Fogarty’s men as a bargaining chip. The Philly mobsters show up at the Stalls’ house, and Tom emerges in a familiar Western hero image—a man on his porch, defending his family with a shotgun. Fogarty offers Jack in exchange for Tom returning with them to Philly. With no choice, Tom agrees, and they release Jack. At that instant, Tom unleashes his inner Joey Cusack on them in another efficient scene of brutal killing. He makes short work of the two henchmen, but Fogarty gets the upper hand. That’s when Jack follows his father’s example once more, using his violence to protect his father by blasting Fogarty with a shotgun. Jack has learned to protect the family home in the same manner as Tom. Both covered in blood, father and son embrace in a symbolic scene that ties them to a cycle of violence passed down from one generation to the next. Whether with Bobby or Fogarty, Jack understands that violence solves conflict. If he ever learns the lasting consequences of these actions, that lesson does not appear onscreen (Tom hints that Bobby’s family may press charges, but nothing comes of that during the film). Furthermore, Tom’s lesson to Jack continues later in the film after he returns from Philly where he violently resolves the conflict with the Irish mob, thus teaching Jack that, under the right circumstances, violence is the great problem solver.

The most challenging scenes in A History of Violence involve Cronenberg’s portrayal of how violence infects Tom and Edie’s marriage, brilliantly and bravely acted by Mortensen and Bello. The scene after Jack kills Fogarty finds Tom in the hospital, where Edie questions him about his identities, Tom Stall and Joey Cusack, and with them, confronts his civilized and brutally violent duality. Edie no longer believes Tom’s initial assertion that Fogarty had the wrong man. She watched him slaughter Fogarty’s men from an upstairs window. “I saw you turn into Joey right before my eyes,” she says. Tom finally admits the truth—that Joey Cusack took the name Tom Stall because “it was available.” Edie asks if he did it for money or pleasure, and his language refers to both identities in the third person: “Joey did, both, Tom Stall didn’t.” Confronted with her husband’s deception and willful split personality, the reality that some part of him is violent and uncivilized, and her own false assessment of her marriage, all she can do is vomit. However, she still loves him and protects the family unit. Later, when Sheriff Sam visits to discuss Tom’s two recent violent encounters, believing there’s more to the story than Tom is letting on, Edie protects her husband’s secret. “Sam,” she deflects, “you’ve got too much time on your hands.”

Violence, in its all-corrupting power, also infects the intimate moments between husband and wife, resulting in A History of Violence’s most controversial scene. Despite the film’s graphic bloodshed and shocking images of bodies torn to shreds by gunshots, it is Cronenberg’s exploration of the link between sex and violence that caused the most uproar. Once Sheriff Sam leaves, Edie retreats upstairs. Tom tries to stop her but she pushes him away. “Fuck you, Joey,” she says with disdain. What unfolds is a scene that begins as domestic violence or an assault, but then transitions into rough sex accented by Tom’s throat-grabbing and Edie’s initial struggle, followed by her embrace of Joey’s aggressive sex. They both become animals who must battle as part of their mating ritual. She makes love to Tom earlier in the film, deepening their marriage and history in an Americana-inflected cheerleader outfit. But she fucks Joey in this tense encounter that momentarily turns her on yet leaves her battered—a scene many critics believed went too far and suggested a rape. However, Cronenberg’s cinema has long linked eroticism to violence in films such as Videodrome (1983); he made an entire film about the sadomasochistic death drive with Crash (1996), and he psychoanalyzed those impulses in A Dangerous Method (2011). Even so, when their aggressive passion ends, Edie pulls away and rushes upstairs to cry alone in the dark on their bed, bruised and traumatized. The scene reveals the full extent of Tom’s other half, but more disturbingly, it also reveals that some suppressed part of Edie enjoys it.

Violence, in its all-corrupting power, also infects the intimate moments between husband and wife, resulting in A History of Violence’s most controversial scene. Despite the film’s graphic bloodshed and shocking images of bodies torn to shreds by gunshots, it is Cronenberg’s exploration of the link between sex and violence that caused the most uproar. Once Sheriff Sam leaves, Edie retreats upstairs. Tom tries to stop her but she pushes him away. “Fuck you, Joey,” she says with disdain. What unfolds is a scene that begins as domestic violence or an assault, but then transitions into rough sex accented by Tom’s throat-grabbing and Edie’s initial struggle, followed by her embrace of Joey’s aggressive sex. They both become animals who must battle as part of their mating ritual. She makes love to Tom earlier in the film, deepening their marriage and history in an Americana-inflected cheerleader outfit. But she fucks Joey in this tense encounter that momentarily turns her on yet leaves her battered—a scene many critics believed went too far and suggested a rape. However, Cronenberg’s cinema has long linked eroticism to violence in films such as Videodrome (1983); he made an entire film about the sadomasochistic death drive with Crash (1996), and he psychoanalyzed those impulses in A Dangerous Method (2011). Even so, when their aggressive passion ends, Edie pulls away and rushes upstairs to cry alone in the dark on their bed, bruised and traumatized. The scene reveals the full extent of Tom’s other half, but more disturbingly, it also reveals that some suppressed part of Edie enjoys it.

Cronenberg uses Peter Suschitzky’s cinematography and Ronald Sanders’ editing like a tactician, rendering A History of Violence with an unflashy, brutal, efficient aesthetic. This is never more evident than during the climactic scenes, when Joey’s crime boss brother Richie calls and invites him home to settle matters. Driving all night, Joey eventually arrives at Richie’s castle-like estate. Whatever problems Joey has caused Richie, they remain siblings. The late Hurt delivers a bizarre, oddly comical, Oscar-nominated performance, calling Joey by his nickname, “Broheim,” and touching foreheads in an intimate gesture. Richie tries to understand why Joey left to become someone else. “You’ve been this other guy almost as long as you’ve been yourself,” Richie observes. But he also acknowledges that violence has always been in their family, passed down from mother to child, from brother to brother: Richie admits, “When mom brought you home from the hospital, I tried to strangle you in the crib—then she smacked me.” Richie intends to finish the job, but Joey makes quick work of Richie’s goons, then his brother. Afterward, he washes up in the lake behind Richie’s mansion. It’s worth noting that he doesn’t use one of Richie’s bathrooms; instead, Joey gives himself a kind of baptism and tosses away his gun, symbolically restoring himself to Tom. The entire encounter keeps Tom away from his family for little more than fifteen minutes of screen time. Another film would have dwelled on the resolution, extending the final act into a bloated sequence of killing to satiate the action-hungry viewer. Cronenberg takes a more discerning and critical approach; the focus of his film isn’t savoring violence but understanding its social, psychological, and emotional implications.

A History of Violence does not propose a solution to violence because Cronenberg recognizes its place beyond social and religious constructs of morality. Following biblical notions in Genesis that separate humankind from beasts—that God created humans in His image to “rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over the cattle and over all the earth”—humans consider themselves above Nature. Violence, then, becomes antithetical to civilization’s view of itself. But violence is not right or wrong in Cronenberg’s view; it’s part of Nature, and so are humans. Cronenberg’s film considers violence an intractable component that humans try to suppress, control, or moralize to further separate our species from animals. Still, as Tom’s chosen name suggests, to deny our fundamental violence is just stalling until the inevitable breakthrough. Tom and his entire family seem to understand this when he returns home the next evening, after killing Richie and ensuring his family’s safety. It might be a happy ending, except the solemn, wordless scene finds Tom in a doorway. A moment passes before Sarah sets him a place, takes his hand, and walks him to the table. Jack then passes the meatloaf. Finally, Edie looks up at him, and her husband returns her gaze. Who does she see sitting there? It’s not Joey Cusack and not Tom Stall either. It’s more ambiguous and uncertain than either single identity. The final image is a haunting recognition that their American Dream has been demystified. No longer can they pretend to be teenagers or convince themselves that their perfect nuclear family meets the requirements of a cultured and advanced civilization. Their family has been infected, incurably, by violence.

The film’s example, the Stall family, provides a pointed specimen that caused many critics in 2005 to interpret the film as a representation of violence in American homes, almost exclusively so. The rhetoric after A History of Violence debuted at the Cannes Film Festival used the framework of Cronenberg as an outsider-Canadian filmmaker commenting on America as “a country that reveals its dark side when provoked by an outside menace.” By extension, some understood the film to critique the second Bush Administration’s Old Testament “eye for an eye” rationale for the “war on terror” and invasion of Iraq as a response to the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon. While that timely analogy certainly rang true in 2005, critic Andrew O’Hehir correctly observed, “despite his reputation as a gore-monger, Cronenberg is too meticulous and thoughtful an artist to be boxed into some narrow political critique.” Indeed, at the Cannes press conference, Cronenberg told reporters, “There’s not a nation in the world that was not founded on violence of some kind, and the suppression of native peoples or whoever happened to own the territory before. So, if you want to get philosophical about it, we’re talking about the human condition, rather than just a particular US kind of focus.” Thus, the Americanness in A History of Violence supplies just one cultural example among many potential representations of humankind’s violent ends.

The film’s example, the Stall family, provides a pointed specimen that caused many critics in 2005 to interpret the film as a representation of violence in American homes, almost exclusively so. The rhetoric after A History of Violence debuted at the Cannes Film Festival used the framework of Cronenberg as an outsider-Canadian filmmaker commenting on America as “a country that reveals its dark side when provoked by an outside menace.” By extension, some understood the film to critique the second Bush Administration’s Old Testament “eye for an eye” rationale for the “war on terror” and invasion of Iraq as a response to the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon. While that timely analogy certainly rang true in 2005, critic Andrew O’Hehir correctly observed, “despite his reputation as a gore-monger, Cronenberg is too meticulous and thoughtful an artist to be boxed into some narrow political critique.” Indeed, at the Cannes press conference, Cronenberg told reporters, “There’s not a nation in the world that was not founded on violence of some kind, and the suppression of native peoples or whoever happened to own the territory before. So, if you want to get philosophical about it, we’re talking about the human condition, rather than just a particular US kind of focus.” Thus, the Americanness in A History of Violence supplies just one cultural example among many potential representations of humankind’s violent ends.

Cronenberg’s film recognizes that violence appears in human behavior in a myriad of ways—familial hierarchies, self-defense, gun fetishism, domestic violence, sexual power, revenge, misogyny, rebellion, and criminal enterprise, to name a few. Through A History of Violence, he invites the viewer to explore these effects and confront their place beneath the universal social construction of civilization. To achieve those ends, his cast and screenplay conceal their thematic substance behind an accessible frontage—a form-follows-function deception that likens the film’s commercial exterior to the pretense of civilization. Underneath, there’s an untreatable infection of violence incubating. To be sure, Cronenberg’s few touches of violent action and gore remain shocking in their speed and potency, and far more confronting than violence in a traditional Hollywood production. A History of Violence dramatizes how human beings call themselves civilized, but in the full span of human existence, that adjective has been around for a short time—and if current events are any indication (though, this could be applied to any point in human history), the term “civilization” is hardly apt. In one of his richest works of entertainment as social deconstruction, Cronenberg considers how, inside everyone, some more than others, a primordial, lizard-brained creature not unlike Joey Cusack is just waiting to escape its cage in our subconscious—and that might be the most unsettling notion in any of his films.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on March 24, 2022.)

Bibliography:

Balibar, Étienne. Trans. G. M. Goshgarian. Violence and Civility: On the Limits of Political Philosophy. Columbia University Press, 2015.

Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press, 2006.

Browning, Mark. David Cronenberg: Author or Filmmaker? Intellect, Ltd., 2007.

Dunlap, Aron, and Joshua Delpech-Ramey. “Grotesque Normals: Cronenberg’s Recent Men and Women.” Discourse, vol. 32, no. 3, Wayne State University Press, 2010, pp. 321–37, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389855. Accessed 2 March 2022.

Ebert, Roger. “Darwinian violence descending.” RogerEbert.com, 22 September 2005. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/a-history-of-violence-2005. Accessed 2 March 2022.

Johnson, Brian D. “Violence Hits Home.” Maclean’s, 17 October 2005. https://archive.macleans.ca/article/2005/10/17/violence-hits-home. Accessed 2 March 2022.

Mathijs, Ernest. The Cinema of David Cronenberg: From Baron of Blood to Cultural Hero. Wallflower Press, 2008.

Rodley, Chris, editor. Cronenberg on Cronenberg. Faber and Faber, 1992.

Schweitzer, Albert. The Philosophy of Civilization. Prometheus; Revised Edition, 1987.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review