The Definitives

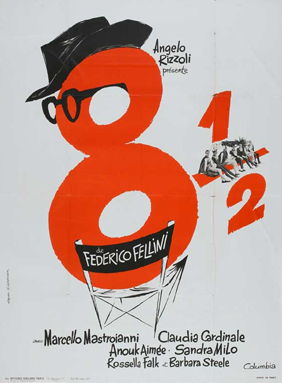

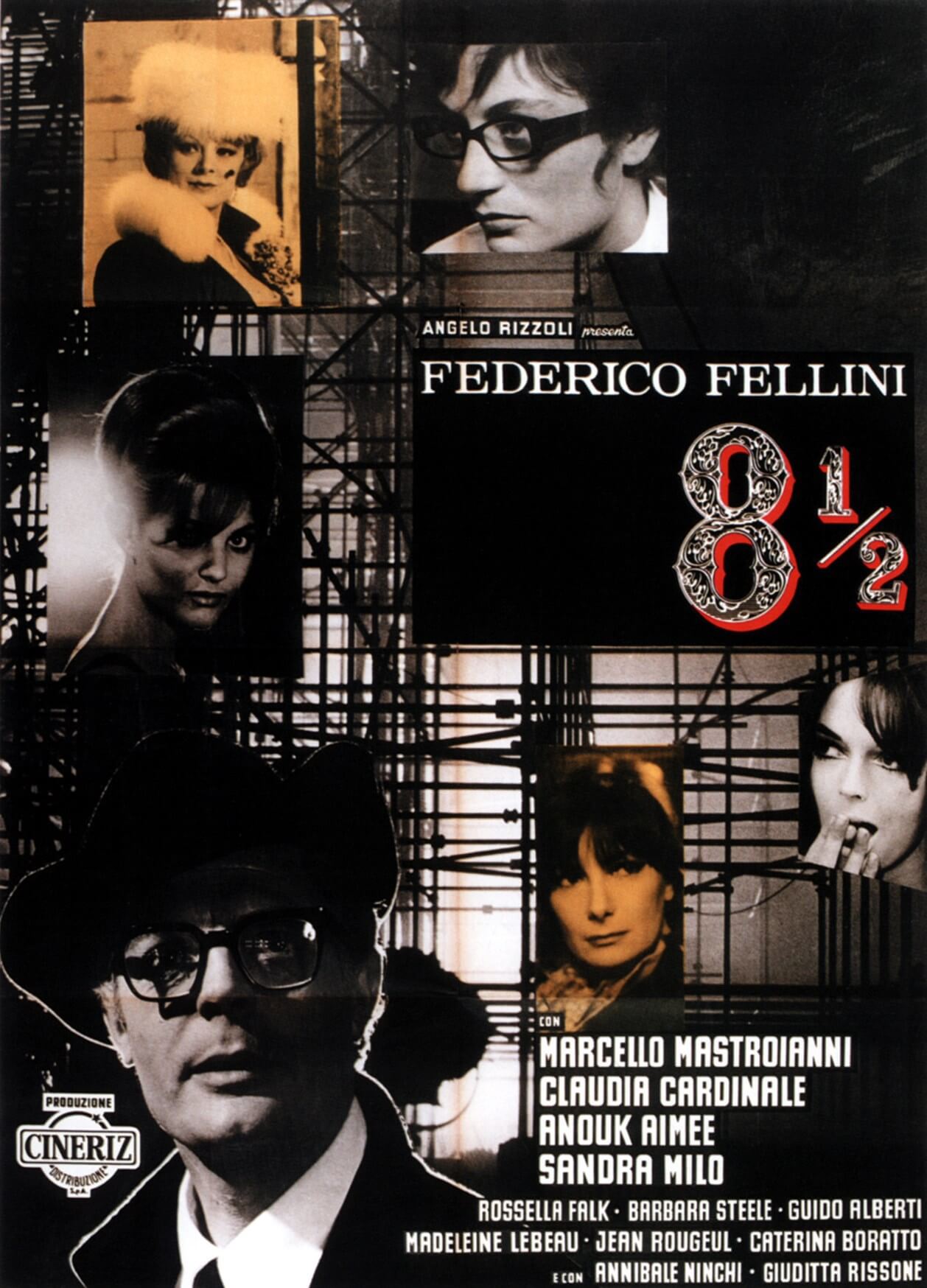

8 1/2 (1963)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

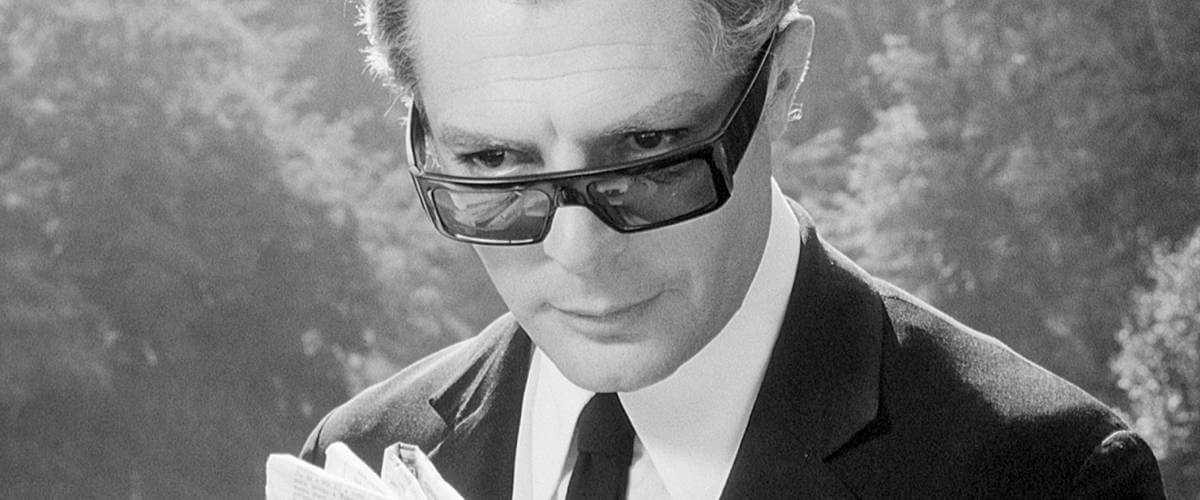

Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ opens with a dream sequence that embodies the entire picture as few first scenes have. In the sequence, troubled filmmaker Guido Anselmi, a clear representation of Fellini himself, escapes a stifling traffic jam of grotesque faces by climbing out of his vehicle and soaring above it. He floats over rows of cars and ascends into the clouds, flying free, until suddenly he notices a rope around his ankle. The shot looks down from above, and it’s actually Fellini’s ankle we see in the frame. Down below, his associates have tethered him like a human kite. They pull him back to Earth, back to reality. When Guido awakes, he finds himself in his room at a health spa. One of his associates has a list of reasons Guido’s latest project will not work, a list that may prevent Guido’s dreams from being put to film. Played by Marcello Mastroianni, Guido is Fellini’s way of injecting himself into his picture through the character’s memories, experiences, and fantasies. Everything about this marvelous film-about-film had a real-life parallel for Fellini; just as within his film, what his characters say about Guido’s proposed production becomes true of 8 ½. To be sure, this is a film of layers both on and off-screen, where reality and fantasy weave together by artistic and autobiographical strokes of genius. It is a rare sort of film, and so thoroughly shaped by its auteur creator. And while its purpose may be elusive upon first viewing, its magic draws you back again and again. With every screening, you discover more layers and further understand the film’s purpose, and its filmmaker.

Before he approached 8 ½, Fellini was responsible for seven-and-a-half films by his count: six full-length features, two shorts totaling one, and a co-director collaboration he counted as another half-film. As his self-referential title suggests, the Italian maestro’s new film would be about himself and filmmaking, and the struggle to find a suitable subject for his latest project, his own eighth-and-a-half feature. Using a series of real-life parallels, his protagonist, Guido, would experience the same crisis of inspiration that Fellini had experienced while initially conceiving 8 ½, and through him, Fellini would create an unprecedented work of self-indulgent art. French critic Christian Metz wrote, “It is not only a film about the cinema, it is a film about a film that is presumably itself about the cinema; it is not a film about a director, but a film about a director who is reflecting himself onto his film.” But if there is one element in the film that does not have an equal in reality, it is that Fellini was in no way creatively bankrupt when making 8 ½. Quite the opposite. Fellini thought and rethought about every frame of this visual spectacle before it reached the screen, pouring himself into it; and in the end, he injected every creative impulse he had into the final film. Fellini saw cinema as a way to express himself as a means of survival, or at least the survival of his ego. Here his faith, past, infidelities, erotic drives, and perhaps above all his uncertainty as a filmmaker make their way onto the screen in an impossibly imaginative and technically brilliant motion picture.

Guido’s rather encumbered perspective on his cinema is much the same as Fellini’s. “I thought I had in my mind something so simple to say,” the character remarks. “Now my mind is totally confused.” Much of 8 ½ follows Guido in that confused state. He labors over the idea for his next film, a science-fictioner whose plot remains a secret, although a 230-foot-high set exists in an empty field. Everyone wants more details, but Guido hides away at a health spa, receiving a prescription of mud baths, mineral water treatments, and doses of holy water in 15-minute intervals. An aged group of patients—old men in visors, nuns, women in sun hats carrying umbrellas, all of whom want the same “cure”—surrounds him. His producers, crewmembers, and a gaggle of actresses hound him for information about their role in his latest film. And then there’s Daumier, a French intellectual and Guido’s collaborator, who deems Guido’s screenplay “A suite of absolutely gratuitous episodes. One wonders what the authors intend.” In truth, Guido’s sci-fi concept seems almost pointless next to his personal obsessions; much like Guido himself, his proposed film is preoccupied with elements from his past, personal life, and reveries. And rather than focus on sorting out his project, he distracts himself further by inviting not only his mistress, the voluptuous tart Carla (Sandra Milo), but also his slim and smart wife Luisa (Anouk Aimée) to join him at the spa. Indeed, Guido seems to create this chaotic environment for himself, yet his self-important side naïvely believes that because he is a genius everyone should openly embrace him, regardless of his behavior. He thinks, “Happiness consists of being able to tell the truth without hurting anyone.” All the while, Guido is overwhelmed with ideas and feelings that contradict one another.

Guido’s rather encumbered perspective on his cinema is much the same as Fellini’s. “I thought I had in my mind something so simple to say,” the character remarks. “Now my mind is totally confused.” Much of 8 ½ follows Guido in that confused state. He labors over the idea for his next film, a science-fictioner whose plot remains a secret, although a 230-foot-high set exists in an empty field. Everyone wants more details, but Guido hides away at a health spa, receiving a prescription of mud baths, mineral water treatments, and doses of holy water in 15-minute intervals. An aged group of patients—old men in visors, nuns, women in sun hats carrying umbrellas, all of whom want the same “cure”—surrounds him. His producers, crewmembers, and a gaggle of actresses hound him for information about their role in his latest film. And then there’s Daumier, a French intellectual and Guido’s collaborator, who deems Guido’s screenplay “A suite of absolutely gratuitous episodes. One wonders what the authors intend.” In truth, Guido’s sci-fi concept seems almost pointless next to his personal obsessions; much like Guido himself, his proposed film is preoccupied with elements from his past, personal life, and reveries. And rather than focus on sorting out his project, he distracts himself further by inviting not only his mistress, the voluptuous tart Carla (Sandra Milo), but also his slim and smart wife Luisa (Anouk Aimée) to join him at the spa. Indeed, Guido seems to create this chaotic environment for himself, yet his self-important side naïvely believes that because he is a genius everyone should openly embrace him, regardless of his behavior. He thinks, “Happiness consists of being able to tell the truth without hurting anyone.” All the while, Guido is overwhelmed with ideas and feelings that contradict one another.

Fellini conceived 8 ½ much like Guido conceives his film, through a fluster of internal influences. After his international hit La dolce vita in 1960, Fellini was creatively exhausted and, for the first time in his directorial career, found himself without a new concept ready. Historically, the idea for his next project was already in the pipeline during post-production on his then-current film. But with the whirlwind success of La dolce vita, Fellini experienced something he had never experienced before as a filmmaker: He had no idea what to do next. While weighing his options, he finally consulted his screenwriting team of Tullio Pinelli, Ennio Flaiano, and Brunello Rondi, about the idea of turning his crisis of inspiration into the theme of his new film. Flaiano suggested an appropriate title, La bella confusion, and Fellini wanted Marcello Mastroianni (who played a thinly veiled version of Fellini in La dolce vita) back as his protagonist. Nevertheless, Fellini could not decide the character’s occupation. Should he be a professor, an architect, or a writer with a nasty bout of writer’s block? He mulled over the proposed concepts and leaned toward a writer, because at least he could understand writer’s block. Then Michelangelo Antonioni’s film La notte, which starred Mastroianni as a novelist, debuted in 1960, and Fellini doubted Mastroianni would want to play another writer. Frustrated, he began casting calls and traveling around Italy to see actors, talking to his cinematographer about the look of his proposed project, hiring technicians, all before anyone involved knew what they were signed up for—much like in the finished film. Unsure of how to proceed, Fellini occupied himself by shooting segments of Boccaccio ’70, a mosaic featuring various tales of Eros, released in 1962.

And then the eureka moment came when Fellini realized that, since he wanted to tell his own story anyway, his protagonist should be a film director. Once Fellini settled on Guido’s occupation, he and his writers had a lark incorporating real-life parallels into the screenplay. Names changed, of course, but the characterizations of people Fellini knew in the real world were evident. Though he had a basic concept now, he nonetheless proceeded with hesitation and doubt, focusing his energy on procrastination, conceiving ways he might delay the shoot, and foreseeing what he saw as his inevitable collapse. He believed all the great filmmakers had only about a decade before their most pure inspiration ran out (Fritz Lang, G. W. Pabst, Jean Renoir, and others fit this description, according to Fellini), and his time was up. Meanwhile, the screenplay was unlike any screenplay Fellini had yet written, filled with descriptions of what should happen as opposed to how it should happen. Either Fellini wanted to improvise on the set, which is something he was famous for, or the director had no clear vision beforehand of how each scene should progress. At least he had settled on a title, another self-reflective flourish that made specific reference to Fellini’s filmography, therein leaving no doubt who the film’s protagonist was meant to represent. The newly titled 8 ½ would be Fellini’s humorous take on the subject of artistic blockage, and on the title page under 8 ½, he typed “A Comedy” to remind himself as such.

And then the eureka moment came when Fellini realized that, since he wanted to tell his own story anyway, his protagonist should be a film director. Once Fellini settled on Guido’s occupation, he and his writers had a lark incorporating real-life parallels into the screenplay. Names changed, of course, but the characterizations of people Fellini knew in the real world were evident. Though he had a basic concept now, he nonetheless proceeded with hesitation and doubt, focusing his energy on procrastination, conceiving ways he might delay the shoot, and foreseeing what he saw as his inevitable collapse. He believed all the great filmmakers had only about a decade before their most pure inspiration ran out (Fritz Lang, G. W. Pabst, Jean Renoir, and others fit this description, according to Fellini), and his time was up. Meanwhile, the screenplay was unlike any screenplay Fellini had yet written, filled with descriptions of what should happen as opposed to how it should happen. Either Fellini wanted to improvise on the set, which is something he was famous for, or the director had no clear vision beforehand of how each scene should progress. At least he had settled on a title, another self-reflective flourish that made specific reference to Fellini’s filmography, therein leaving no doubt who the film’s protagonist was meant to represent. The newly titled 8 ½ would be Fellini’s humorous take on the subject of artistic blockage, and on the title page under 8 ½, he typed “A Comedy” to remind himself as such.

Similarly, Fellini kept a piece of paper taped to the camera while shooting that read, “Remember, this is a comedy.” Principal photography began on May 9, 1962, and all at once Fellini found the film’s concept liberating and challenging to shoot. In one respect, he could pour himself onto the screen; in another respect, the daily shoots were filled with moments of on-set inspiration and a neverending list of impulsive changes. Mastroiannai noted that, “Once he starts shooting, Federico always changes everything. Then he rewrites lines during the dubbing and then changes everything again.” Typical for Italian filmmakers of the era, Fellini played music on the set during each scene to set the mood, and then synchronized the dialogue in post-production. His actors often received only a sheet of paper with their lines for the day’s shoot, never the full script. And to get to the root of his protagonist, he limited the number of locations used in the film. Whereas La dolce vita was all about great locations in Rome, in 8 ½ there are only a handful of real-life locations, and the rest exist inside Guido’s imagination. As a result, Fellini relied on his crew to do more with less. For example, cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo was aware that black-and-white photography was a minority choice at that time, and shooting 8 ½ may even be his final opportunity to film this way. Venanzo worked with production designer Piero Gherardi to design sets “out of light” rather than building elaborate constructions. Despite the creativity all around him, and given the internal and self-reflexive subject matter, Fellini was more than ever subject to his own moodiness, not unlike Guido. And he was surrounded by more desirable women than there were such characters in the film. Though an actress or two tried to seduce him, the irony was too great and Fellini did not engage—at least, not any more than he already had. (After all, Fellini was currently having an on-again-off-again affair with Milo, who was playing his onscreen counterpart’s mistress as well.)

Shooting lasted until October 14, 1962, and the finished film premiered in Milan on February 14 the following year. When audiences first saw 8 ½, there was no mistaking it as a product of Federico Fellini, since, for the first time in his career, his name appeared above the title. And though he never appears onscreen, everyone recognized that Fellini was the star of his film. 8 ½ received enthusiastic praise from the majority of critics, many of whom offered apt comparisons to the work of Ingmar Bergman, namely his film Wild Strawberries (1957). A few critics accused Fellini of narcissism, going as far as to compare him to Leopold Bloom in James Joyce’s Ulysses, but such attacks were few. The consensus was this: Fellini is a genius, and the film is one of his best. Neoavanguardia intellectuals—a group of Italian critics, novelists, and poets who rebel against everything mainstream and adhere to artistic values—proclaimed Fellini’s film to be vastly influential on the future of authorship in cinema and beyond. Abroad, the film took home two Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Costume Design, and it was nominated for three more. At the Moscow International Film Festival, it took home the Grand Prize, which worried the Soviets because the response seemed to revel in the film’s individualism (a dangerous idea in a communist state). Years later, the film would influence Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories and inspire Maury Yeston’s Tony Award-winning musical called Nine, which debuted in 1982, and was later adapted into an underwhelming film by Rob Marshall in 2009.

Shooting lasted until October 14, 1962, and the finished film premiered in Milan on February 14 the following year. When audiences first saw 8 ½, there was no mistaking it as a product of Federico Fellini, since, for the first time in his career, his name appeared above the title. And though he never appears onscreen, everyone recognized that Fellini was the star of his film. 8 ½ received enthusiastic praise from the majority of critics, many of whom offered apt comparisons to the work of Ingmar Bergman, namely his film Wild Strawberries (1957). A few critics accused Fellini of narcissism, going as far as to compare him to Leopold Bloom in James Joyce’s Ulysses, but such attacks were few. The consensus was this: Fellini is a genius, and the film is one of his best. Neoavanguardia intellectuals—a group of Italian critics, novelists, and poets who rebel against everything mainstream and adhere to artistic values—proclaimed Fellini’s film to be vastly influential on the future of authorship in cinema and beyond. Abroad, the film took home two Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Costume Design, and it was nominated for three more. At the Moscow International Film Festival, it took home the Grand Prize, which worried the Soviets because the response seemed to revel in the film’s individualism (a dangerous idea in a communist state). Years later, the film would influence Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories and inspire Maury Yeston’s Tony Award-winning musical called Nine, which debuted in 1982, and was later adapted into an underwhelming film by Rob Marshall in 2009.

The parallels between Fellini’s life and the events onscreen were undeniable, leading to speculation about the film’s every detail. Only after the film’s release did the director admit, “I am Guido,” and from then onward he was open about the film’s correlations to his own life. Reports that the director had been in Jungian-style psychoanalysis offered an explanation as to why 8 ½ explored its autobiographical subject as openly as it did. Since about 1959, the director had seen Jungian disciple, Dr. Ernst Bernhard, three times a week, though both Fellini and Bernhard denied as much later. Fellini claimed he only consulted a psychoanalyst for material. But the maestro was fixated on Jungian theorists and followers; he even visited The Bollingen Tower site on Lake Zürich, one of many homes owned by the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung. Bernhard’s treatment consisted of exploring the life that exists inside the mind. Over the years, Bernhard and Fellini had become great friends, and together they opened in Fellini a new way of thinking, and a new rhetoric—both thematic and visual—in which he could express himself. Jungian theory suggests that an extrovert, like Fellini, will recoil into fantasy if life is too stressful. And it is the interpretation of those fantasies and dreams that is the gateway to a person’s self-understanding. He encouraged the filmmaker to keep a dream journal, which Fellini cataloged over the years, keeping many volumes. Fellini, who since La strada (1954) had blended realism with fantasy, once said, “What I admire most ardently in Jung is the fact that he found a meeting place between science and magic, between reason and fantasy.” Unquestionably, Jungian concepts outline many of the elements that define a Felliniesque picture, as Fellini’s preoccupation with his internal thoughts, memories, desires, anxieties, and dreams consume his films. Perhaps more than any other Fellini film, 8 ½ transitions in and out of these various worlds, using Fellini and therein Guido’s conscious and unconscious mind as a playground.

Consider how 8 ½ explores segments of Guido’s past, transitioning into flashback during similar moments in the character’s present. In one of the film’s most famous scenes, which derives from Fellini’s memories, Guido remembers himself as a boy who, after skipping Catholic school, arrives on a beach with his friends to watch as the Rubenesque woman Saraghina, played by Eddra Gale, performs a sultry rumba. It’s a formative moment in both the director-character’s sexuality and, unlike Guido’s uncertain future, this scene from his past represents a rare point of clarity. 8 ½ has a romantic fondness for its scenes in Guido’s past, and as a result, his unconscious bleeds that association into his present. For example, the spa itself seems to exist entirely within Guido’s perceptions of the past, where the band plays Wagner’s intense “Ride of the Valkyries” (an unlikely and boisterous choice for a calming spa), the old attendees don 1930s dress, and the structures look like they belong from the same period. Has Guido projected these details onto the spa, linking his present to his past? Over the years, critics and viewers have had difficulty deciphering where Guido’s reality ends and where his memories and fantasies begin, but the secret is simple: whenever Guido’s reality becomes too much to bear, he escapes into a memory or fantasy that eases his current predicament. Though Guido’s pretentious writer Daumier insists, “You must be clear to get your point across,” Fellini explores his past, present, and fantasies in a film that transitions between them without warning, and also layers them atop one another, sometimes in a single scene or shot.

Consider how 8 ½ explores segments of Guido’s past, transitioning into flashback during similar moments in the character’s present. In one of the film’s most famous scenes, which derives from Fellini’s memories, Guido remembers himself as a boy who, after skipping Catholic school, arrives on a beach with his friends to watch as the Rubenesque woman Saraghina, played by Eddra Gale, performs a sultry rumba. It’s a formative moment in both the director-character’s sexuality and, unlike Guido’s uncertain future, this scene from his past represents a rare point of clarity. 8 ½ has a romantic fondness for its scenes in Guido’s past, and as a result, his unconscious bleeds that association into his present. For example, the spa itself seems to exist entirely within Guido’s perceptions of the past, where the band plays Wagner’s intense “Ride of the Valkyries” (an unlikely and boisterous choice for a calming spa), the old attendees don 1930s dress, and the structures look like they belong from the same period. Has Guido projected these details onto the spa, linking his present to his past? Over the years, critics and viewers have had difficulty deciphering where Guido’s reality ends and where his memories and fantasies begin, but the secret is simple: whenever Guido’s reality becomes too much to bear, he escapes into a memory or fantasy that eases his current predicament. Though Guido’s pretentious writer Daumier insists, “You must be clear to get your point across,” Fellini explores his past, present, and fantasies in a film that transitions between them without warning, and also layers them atop one another, sometimes in a single scene or shot.

Fellini’s fantasies account for 8 ½’s most entertaining, surreal sequences. At one point, Guido finds himself at the center of a house populated by women he has slept with or fanaticized about—the harem of King Solomon, he calls it. In addition to his wife Luisa, his mistress Carla, and Saraghina, Guido’s harem includes his sister-in-law (Elizabetta Catalano), an aged showgirl (Yvonne Casadei), a flight attendant (Nadine Sanders), and an exotic dancer (Hazel Rogers), among others. The whole female extravaganza is set to composer Nino Rota’s circus melodies, with each of the women behaving as if unquestionably devoted to Guido. Each treat him as child, father, and lover. They even appear grateful when others join the harem. “He’s a darling,” says one woman, looking directly at the camera. “He acts like a boy. But he’s really very complex,” observes another woman. (At least Fellini is aware of his own male absurdity and hypocrisies.) In reality, Guido is unable to manage the women flooding his life, memories, and fantasies. And so, he wishes he could control them like a ringmaster, cracking a literal whip when they become unruly. But he cannot control them. He has no control. The harem sequence ends in melancholy: Luisa scrubs the floor and asks Guido, “When will you truly make me your wife?” Shame, guilt, and thoughts of his wife Giulietta Masina no doubt flooded Fellini in this scene. Much later in life, Fellini’s co-writer Tullio Penelli asked him about his relationships with women, to which Fellini replied, “See the harem scene in 8 ½; it’s like that.”

A sequence like this may be an obvious male fantasy, but 8 ½ is nothing if not self-aware about its own obviousness, which in turn makes it incredibly clever in its post-modern conceit. Within the film, Fellini admits when its symbolism is a cliché. For example, take the pureness of his mineral water fantasy girl, played by Claudia Cardinale. At the spa, she glides onscreen like an angel, as if carried by her beauty, and then a moment later Guido snaps out of his fantasy and the woman is just a normal spa worker. While the image and idea of purity may be a cliché, Fellini turns that idea on its head later on when Claudia’s character turns out to be a clingy actress just like the rest, not pure at all. The director’s self-awareness also manifests in uncomfortable parallels. Guido’s producer Mezzabotta (Mario Pisu), who is accompanied by a young girlfriend Gloria (Barbara Steele) are thin disguises for real-life producer Carlo Ponti and Sophia Loren. Such parallels occur within the film too. When Guido watches rushes of actresses he’s tested, Luisa sees herself interpreted onscreen by a performer; she also sees actresses interpret her husband’s known mistress, Carla. In some respect, Fellini’s wife Masina must have seen herself reflected in Luisa, and since Carla is meant to represent Fellini’s long-time mistress Anna Giovannini, who was played by another real-life fling, Sandra Milo, the parallel must have been doubly painful for Masina. Later in the film, Claudia tells Guido that his kind of character is not very sympathetic, and he knows it. Fellini must have known this too.

A sequence like this may be an obvious male fantasy, but 8 ½ is nothing if not self-aware about its own obviousness, which in turn makes it incredibly clever in its post-modern conceit. Within the film, Fellini admits when its symbolism is a cliché. For example, take the pureness of his mineral water fantasy girl, played by Claudia Cardinale. At the spa, she glides onscreen like an angel, as if carried by her beauty, and then a moment later Guido snaps out of his fantasy and the woman is just a normal spa worker. While the image and idea of purity may be a cliché, Fellini turns that idea on its head later on when Claudia’s character turns out to be a clingy actress just like the rest, not pure at all. The director’s self-awareness also manifests in uncomfortable parallels. Guido’s producer Mezzabotta (Mario Pisu), who is accompanied by a young girlfriend Gloria (Barbara Steele) are thin disguises for real-life producer Carlo Ponti and Sophia Loren. Such parallels occur within the film too. When Guido watches rushes of actresses he’s tested, Luisa sees herself interpreted onscreen by a performer; she also sees actresses interpret her husband’s known mistress, Carla. In some respect, Fellini’s wife Masina must have seen herself reflected in Luisa, and since Carla is meant to represent Fellini’s long-time mistress Anna Giovannini, who was played by another real-life fling, Sandra Milo, the parallel must have been doubly painful for Masina. Later in the film, Claudia tells Guido that his kind of character is not very sympathetic, and he knows it. Fellini must have known this too.

While each parallel contains some autobiographical truth, each contains an element of Fellini’s fabulist subjective truth as well. More than an accurate depiction of his past, present, and fantasy worlds, Fellini seeks to represent his own psychological state and blends reality and dreams, quite often deceptively so. To do this, the director creates an anxious tempo that leaps from one moment to the next with all the impulsiveness of the unconscious mind. Though Fellini may not have the intentional control of Alfred Hitchcock or Stanley Kubrick, he relays his own psychological state in all its frenzied glory, even though at times his psychological expulsion may seem lessened by the way he disguises his confessions in stylistic abandon. But 8 ½ is less about cataloging Fellini’s personal hang-ups than his process of accepting them. In the film’s original, unused ending, Guido and his wife sit in the dining car on a train; the other passengers are people from Guido’s life, all smiling at him approvingly. Despite the apparent approval, the moment would have had a creepy undertone if left in the film, because it never explains where the train was going. (Hell or heaven, perhaps? Back to reality? Who can say?) Fellini shot the film’s actual ending, where a parade of characters dance around Guido’s sci-fi setpiece, as a theatrical trailer, using eight cameras. This final ending exists as an antithetical Dance of Life to counteract the clear influence from the Dance of Death at the end of Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957, yet another Bergman influence on 8 ½), This ending marks a celebration of self-acceptance. Fellini told one interviewer, “Self-acceptance can occur only when you’ve grasped that the only thing that exists is yourself, your true, deep self which wants to grow spontaneously, but which is fettered by inoperative lies, myths and fantasies that propose an unattainable morality or sanctity or perfection—all of it brainwashed into us during our defensive childhood.”

Self-acceptance became Fellini’s mark as an auteur. In the 1950s, international cinema produced a number of auteurs championed in the pages of French film magazine Cahiers du cinéma. The French critics praised directors who made films that articulated their distinctive voice, perspective, and thematic preoccupations, just as an author is responsible for the content of a novel. Bergman, Satyajit Ray, Howard Hawks, Jacques Tati, Nicholas Ray, and Hitchcock (who literally put himself into his films) each participated, either knowingly or not, in a movement of individualized filmmaking that today does not exist at the same level of control. As auteurism was celebrated in many circles during this era, the studios responded, as always, by giving audiences what they wanted. Over the coming years, they handed over larger and larger budgets to auteur directors. But larger budgets for such personal projects were more difficult to recover at the box-office, and suddenly auteurs were not bankable when given a blank check for their self-indulgent artistic freedom. Among several financial disasters, William Friedkin’s Sorcerer (1977) and Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980) saw to it that the studios would not give over blockbuster-sized budgets to fund an auteur passion project. And while artist-directors were still allowed to make films, their ambitions were curtailed by studios who demanded a bankable product. Moreover, the preponderance of commercialized cinema limited the freedom of auteurs and ensured that films comparable to 8 ½ would almost never be made except by maverick directors and producers. Rare exceptions include Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), Spike Jonze’s Being John Malkovich (1998) or Adaptation (2002), or lately Michael Keaton’s turn in Birdman: Or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) from 2014.

Self-acceptance became Fellini’s mark as an auteur. In the 1950s, international cinema produced a number of auteurs championed in the pages of French film magazine Cahiers du cinéma. The French critics praised directors who made films that articulated their distinctive voice, perspective, and thematic preoccupations, just as an author is responsible for the content of a novel. Bergman, Satyajit Ray, Howard Hawks, Jacques Tati, Nicholas Ray, and Hitchcock (who literally put himself into his films) each participated, either knowingly or not, in a movement of individualized filmmaking that today does not exist at the same level of control. As auteurism was celebrated in many circles during this era, the studios responded, as always, by giving audiences what they wanted. Over the coming years, they handed over larger and larger budgets to auteur directors. But larger budgets for such personal projects were more difficult to recover at the box-office, and suddenly auteurs were not bankable when given a blank check for their self-indulgent artistic freedom. Among several financial disasters, William Friedkin’s Sorcerer (1977) and Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980) saw to it that the studios would not give over blockbuster-sized budgets to fund an auteur passion project. And while artist-directors were still allowed to make films, their ambitions were curtailed by studios who demanded a bankable product. Moreover, the preponderance of commercialized cinema limited the freedom of auteurs and ensured that films comparable to 8 ½ would almost never be made except by maverick directors and producers. Rare exceptions include Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), Spike Jonze’s Being John Malkovich (1998) or Adaptation (2002), or lately Michael Keaton’s turn in Birdman: Or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) from 2014.

Fellini was a rare kind of auteur who, in 8 ½, used his auteurism to remember his past, question his present, and express his fantasies. More than any other Fellini picture, his theme is himself, and the process of understanding himself enough so that he could be committed to celluloid. At one point in the film, an interviewer asks Guido if he has any children. Guido responds instinctively: “Yes… I mean no.” It is not that Guido forgets whether he has children; rather, his children are his films, a concept an interviewer would not understand. With the limelight of auteurism in the past, something as pure and self-indulgent as 8 ½ must be celebrated and not forgotten, nor taken for granted—even if auteurs are considered unfashionable and certainly not economically viable today. French critic André Bazin believed auteurs risked “an aesthetic cult of personality”, but he wrote that in a time when such personalities in cinema were more common. Today, distinctive personalities are exactly what cinema needs, and yet they are wholly deficient. Fellini’s decadent filmmaking style and self-obsessed storytelling feels more desirable than ever against the swells of homogenized Hollywood product. Though it once topped critic polls for being one of the best films ever made, 8 ½ seems overlooked today because its influence is now almost commonplace, having resulted in a niche of self-reflexive filmmaking that was originated by Fellini. His brilliant film is steeped in surrealist imagery and personal anxieties, and it remains a fiercely accurate depiction of Fellini’s exhausting doubt and nebulous mental state. Cinéastes should never stop rejoicing that, though Fellini felt he had nothing to say, he resolved to say it anyway.

Bibliography:

Albpert, Hollis. Fellini: A Life. New York: Marlowe & Company, 1986.

Aldouby, Hava. Federico Fellini: Painting in Film, Painting on Film. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Bondanella, Peter. The Films of Federico Fellini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Kezich, Tullio. Federico Fellini: His Life and Films. New York: Faber and Faber, Inc., 2002.

Kezich, Tullio. Federico Fellini: The Films. New York: Rizzoli, 1st Edition, 2010.

Miller, D.A. 8 ½. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review