The Definitives

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days opens on a tank of fish resting on a table cluttered with dishes, a newspaper, and a cigarette burning in an ashtray. As a hand reaches for the smoke, the camera pulls back in sharp movements, revealing two undergraduate students in a cramped dorm room. Otilia (Anamaria Marinca) has just agreed to help her friend, Gabita (Laura Vasiliu), obtain an illegal abortion. The setting is Romania in 1987, at the height of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s dictatorship and just two years before its collapse. Mungiu gazes into a historical enclosure, which is so transparent that it fails to cast a reflection. Later in the film, in the final scene after their traumatizing ordeal has ended, Otilia seems to look at the viewer, peering out from the fish tank of history and cinema. This subtle, unpronounced imagery, which illustrates how women were trapped in Communist Romania as subjects of the state, is the only distinct symbolism in a film that avoids intellectualizing or delivering an overt commentary on its historical and social contexts. Having experienced the world of 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days first hand, Mungiu bypasses emotional manipulation, unnecessary explanations, or evaluation that might dampen his film’s utter immersion. In a story that unfolds over a tense 24-hour period, Mungiu steeps us in the everyday, forcing the viewer to understand this world through its discordance with our own.

In the mid-1960s, Ceaușescu’s autocratic rule over communist Romania swiftly earned him the reputation as a feared totalitarian of the Eastern Bloc. Not long after Ceaușescu took power, his administration used a new bill, called Decree 770, to make abortions a crime in most cases. The state had experienced a dramatic decline in birth rates, and Decree 770 made both abortions and contraception illegal in hopes of increasing the Romanian population from 23 million to 30 million. The government ostensibly registered and surveilled every womb as a state apparatus, making it the civic duty of every woman under the age of 45 to give birth to at least five children. Besides expecting women to have more children than they might otherwise, the state forced women to attend monthly gynecological exams. If they failed to have a child by their mid-twenties, they received higher income taxes. Alternatively, like much of the Soviet Union, the Ceaușescu regime celebrated mothers of large families as state heroes, awarding them the honorary title of “Mother Heroine” if they produced ten or more children. Even though their bodies had been turned into veritable baby factories by the state, women were also socially expected to have jobs and maintain the household, making another child a practical impossibility in many cases. To maintain control of their family, many women abandoned newborns at hospitals or simply discarded them with the refuse; others turned to abortion. Women who wanted to become more than a mother or subject of the state were left with few alternatives.

Population studies from the era report that thousands of women died from back-alley abortions between the time of Decree 770 and the Romanian revolution of 1989. Scholar Roxana Cazan notes that, for many Romanian women, abortions were an act of rebellion against the tyrannical political authority—conscious and courageous “dissident citizenship” that sought to reclaim their bodies in defiance of “the state’s attempt to define their wombs as national spaces.” Since Ceaușescu’s power meant that no single woman could completely reclaim her body from state rule, abortions became a small act of resistance, even though women risked infection or death from an unprofessional procedure. The alternative could not be trusted; when contraception was acquired on the black market or through more official channels, it was often found to have been sabotaged in service of the population. Some well-connected Romanian women could pay a doctor or nurse friend to conduct a safe procedure, usually in a clinic setting, albeit kept from official eyes. Others would handle the procedure themselves with homemade solutions or plant-based therapies. The solutions often depended on class and, inevitably, the lower classes with fewer resources represented the highest mortality rate among women who died from abortions.

Like many contemporary Romanian filmmakers, Mungiu examines political and social conditions in his country’s history through his concentration on individual characters, a detailed formal approach, and spare verisimilitude. It’s a realism that cannot help but serve as a biting criticism of the Ceaușescu regime, but it comes almost twenty years after the regime had ended. Unlike the Neorealists in Italy in the 1940s or the Czech New Wave of the 1960s, New Romanian Cinema did not emerge in direct opposition to its contemporary state authority. No national cinema existed under Ceaușescu; much like the women who sought abortions as personal acts of resistance, dissidence was practiced in private spaces and not in a larger movement, certainly not in an organized school of filmmakers. However, for many contemporary Romanian directors, Lucian Pintilie’s example supplied inspiration. His 1968 film Reconstruction takes a faux-documentary style to uncover the banality of evils propelling the Romanian Communist regime. It tells the true story of authorities who force two young students to reenact a drunken fight over and over, thus supplying onlookers with a cautionary tale to the point of dehumanization and humiliation. Pintilie based his film on a book about real-life events witnessed by author Horia Patrascu, and the director used an ultra-realist aesthetic to situate the events in his contemporary Romania. Inevitably, the film was banned by the state and withdrawn from theaters in 1969 when Pintilie refused to cut controversial scenes. Afterward, Pintilie left Romania and would continue to work in film and theater throughout the remainder of Ceaușescu’s rule. The exiled director finally returned in 1990, after the revolution, for a revival screening of Reconstruction, a film that had barely seen the light of day upon its initial release. Pintilie’s work was universally praised and seen as a cultural lightning bolt to energize Romanian cinema.

Dominique Nasta describes Reconstruction as “a bottle full of liberty” that filled the cultural consciousness of Romania and inspired subsequent filmmakers. Still, it took over a decade for the Romanian New Wave to emerge on the international film scene after the screenings of Reconstruction had cleared the way for a generation of filmmakers. It was not until after 2000, the year when the Romanian film industry did not produce a single film, that several notable directors began to earn recognition around the globe: In the West, Cristian Mungiu is perhaps the most recognized on a list of names including Cristi Puiu (The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, 2005), Corneliu Porumboiu (Police, Adjective, 2009), and Călin Peter Netzer (Child’s Pose, 2013). These new Romanian filmmakers took a cue from Pintilie and sought to portray reality with almost documentary attention to everyday life, using functional strategies in form and a resistance to narrative closure that augment their realism. If Reconstruction was a film that “looks strange because it’s so close to our everyday life,” according to critic Eugenia Vodă, the directors in Pintilie’s wake furthered his devotion to authenticity. Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days is among the most well-known and acclaimed films to come out of the Romanian New Wave, followed by his Beyond the Hills (2012) and Graduation (2016). It became the first work of Romanian cinema to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 2007, and like Reconstruction, it marked another landmark moment in Romanian culture.

Mungiu based 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days on an experience that happened to a close friend, and the film’s details seem so impossibly bleak that they must be true. The story opens as Otilia agrees to help Gabita, though it’s initially unclear what they’re setting out to do. Mungiu told an interviewer, “I wanted very much to start the film with the silence that occurs in a conversation right after you have asked somebody for a little more than you should have.” During the first act, Mungui builds tension through fastidious attention to detail and process. After agreeing to help her friend, Otilia buys soap and cigarettes then asks to borrow money from her boyfriend, Adi (Alexandru Potocean). She reluctantly agrees to stop by Adi’s mother’s birthday party later that night. Next, she arranges a hotel room and makes a rendezvous with a stranger named Mr. Bebe (Vlad Ivanov). When Otilia, Gabita, and Bebe meet in the hotel room, they engage in a grueling negotiation process that involves details about Gabita’s pregnancy, the legal risks, and Bebe’s payment. Finally, the words “termination” and “abortion” are used. Bebe does not want money for his services; he expects both women to have sex with him. They have no other choice but to submit to his sexual exploitation of the situation. Afterward, he performs the abortion and leaves them in the hotel room. Gabita must wait on the bed for the procedure to take effect, while Otilia visits Adi’s family as promised and endures some isolating dinner table conversation. When Otilia escapes the conversation and calls the hotel room to check on her friend, Gabita does not answer. She rushes back to discover that Gabita has passed the fetus. Otilia wraps up the remains and follows Bebe’s instructions: she locates a tall building, where she tosses the evidence down a garbage chute. Upon returning, she finds Gabita in the hotel restaurant, and the two agree to never speak of what happened.

Mungiu’s approach has been compared to that of documentary filmmakers. Critic Ella Taylor wrote that his style “resembles the vérité documentaries of Frederick Wiseman or the Maysles brothers,” as opposed to the vibrant aestheticized realism of “social-issue” filmmakers. Upon closer inspection, cinematographer Oleg Mutu’s camera placement proves calculating, but far from purely observational, even as it strips away artifice. The functional, intentional, and exacting camera movements often follow Otilia and align with her subjectivity. In the moments before the abortion, they occupy Gabita’s subjectivity. There are no cranes or dolly shots, not even a Steadicam. Mutu’s camera is entirely handheld. Moreover, Mungiu drains the film of bright colors to punctuate the stifling existence in Romania at the time. When he was developing the footage, he further desaturated the visuals with a bleaching process. Production designer Mihaela Poenaru adds to the visually muted outcome by using objects that adhere to the film’s palette of drab colors. Only Bebe’s red car and the fleshy aborted fetus break from this pattern. The visuals eschew expressivity for its own sake and remain entrenched in the stark realm of Communist Romania. Mungiu even omits a musical score to avoid any hint of emotional emphasis; instead, the sound design amplifies ambient noise such as running water, footsteps, or dogs barking in the distance—and the most unshakable sound, the dull metallic thud as Otilia drops the dead fetus down the garbage chute. The overall effect is an absolute immersion into the sensory and moment-by-moment immediacy of the situation.

Though Mungiu’s film grammar has been said to eliminate “the possibility of visual commentary,” 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days is not without its more expressive touches that underscore the fish tank quality of the film. Mutu’s camera may be handheld, but it often settles back into stationary scenes where the frame is perpendicular to a wall—a perspective that recalls the tableaux angle of the opening shot. In another absorbing technique, many of these long, unbroken sequences last nearly ten minutes, and, due to their handheld nature, the frame has an almost imperceptible movement. We watch intently, like we’re looking into a rectangular vivarium at anthropological specimens, and we see them gently rocking within the frame. It evokes a woozy seasickness. A similar effect takes hold when the camera shakily follows Otilia to the bus stop in two scenes. Mutu remains right behind her, the camera trembling as the operator keeps up, until the frame suddenly comes to a stop and watches Otilia run into the distance to catch her bus. In an instant, the camera switches from a subjective point of view to an objective spectator, from being with a character to seeing her isolated in her world. Both approaches suggest the claustrophobic nature of this restrictive society. In such long scenes filmed in diorama spaces, often accomplished in a single take, the viewer at once has a full picture yet remains aware that a world exists beyond the edges of the frame, like a fish tank. When Mungiu omits something, the effect is jarring. For instance, Bebe’s sexual manipulation of Otilia and Gabita takes place off-screen, whereas Mungiu confronts the viewer with the reality of the aborted fetus. These choices build upon his portrait of the era’s ever-present dread, the uneasy sense that someone is watching or listening at all times. If freedom exists at all, it is internalized. Meanwhile, the Romanian state, either directly or as a result of its repression, penetrates even private, hidden spaces.

Life under a patriarchal totalitarian authority means that even simple tasks become an opportunity for the state to impose itself. When Otilia tries to arrange a room at two different hotels, the clerks interrogate her as the police might, asking for identification and the reasons for the stay. After she secures a room, she follows the unspoken rule of leaving a bribe, a pack of Kent cigarettes. Mungiu painstakingly recreates how Ceaușescu’s regime placed a bureaucratic obstacle at every turn to remind citizens that the state is in control, that submission is the only response. There is a punishing sense of alienation in every encounter. What is more, oppressive states usually have an underground black market, populated by opportunists and corrupt officials willing to bend the rules for the right price. Bebe thrives in this environment. He knows that anyone talking to him must be desperate, and his monstrous negotiation with Gabita and Otilia reveals his tactic of breaking down their resolve with a cruel logic that underscores their limited options. “I’m not judging you,” he tells them, followed by “You’re the ones who came to me for help” and “Did I ever mention money?” Not even the resourceful Otilia can argue against the desperateness of their situation, nor Bebe’s perversion of it. “If I’m nice enough to you and help you,” he says, “you should be nice to me, right?” Bebe’s treatment of women—his verbal abuse of his elderly mother, his sexual manipulation of two young college students, and the frightening tone of reassuring authority he adopts during the abortion—reveals his abuses of power in the patriarchal order. Similarly, Otilia’s boyfriend Adi proves obedient to his culture’s male privilege; he is disinterested, condescending, and simply oblivious to both Otilia and the perspective of women.

Even as Mungiu exposes the viewer to the cruel gender politics of Communist Romania in 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, he also employs Hitchcockian suspense to accent its danger. The director’s strategies of visual confinement and alienation enhance the film’s tension, whereas more traditional modes of suspense turn up as well. Watch the scene as Otilia snoops in Bebe’s briefcase and locates a switchblade while he’s in the bathroom. We hear Bebe finishing up in the background. In a breathless instant when Bebe emerges, Otilia quickly restores the briefcase and conceals the knife in her pocket. Throughout the abortion procedure that follows, she never has the chance to act on the impulse that compelled her to grab and conceal the weapon. But the moment imbues the scene with further dread. There is a similar quality to the birthday party scene, where Otilia sits at the table, listening to a demeaning and long conversation—a clueless discussion about class and the lack of grit among the younger generation—as, far away, her friend waits for her abortion to take effect. Otilia worries, and her call to the hotel room goes unanswered. It’s as though Mungiu has followed Hitchcock’s recipe for suspense and planted a bomb under the table. The audience waits for the bomb to go off, but just as Mungiu resists falling into familiar genre traps, he avoids a typical thriller payoff. The anxiety gives way to Otilia returning to the hotel room and finding Gabita asleep—and, for a brief moment, thought dead—after having had her abortion. Another paranoid scene follows as Otilia heads out into Bucharest at night to dispose of the evidence, aware that every dark silhouette might be someone following her.

At the center of Mungiu’s tale is a friendship between Otilia and Gabita, propelled by Marinca and Vasiliu’s incredible performances. Otilia is proactive, a fixer and doer, responsible and forward-thinking. But Gabita depends on her friend and proves naive about her situation until the final moment. Much to Otilia’s frustration, voiced in a brutal exchange between friends, Gabita has gotten herself pregnant, waited too long to face reality, and lied about how far along she was (“It’s a new offense after the fourth month,” Bebe warns. “You’re not done for abortion. They get you for murder.”). Additionally, she has arranged to meet Bebe without adequate vetting, failed to secure the hotel room, and forgotten the plastic sheet that will prevent her from bleeding onto the bed. At every turn, her irresponsibility forces Otilia into a compromising situation. Worse, she treats the abortion procedure like she was “going to a wedding,” as Otilia observes, and waxes her legs for the occasion. Though she proves selfishly demanding of her friend, and her assumptions and poor decisions have exacerbated the situation, Gabita’s chastisement by her friend feels overly harsh. Although it would be easy to dislike Gabita for her behavior, she deserves empathy given the shared sense of nauseating physical pain and trauma we experience along with her. Otilia’s last remark about the situation (“I’m just upset that things ended up this way”) articulates their shared nightmare as women in this time and place. In the final shot, when a server brings a plate of “beef, liver, breaded brains, and marrow” on the menu from a wedding party at the hotel, the stomach-churning moment bonds them once more.

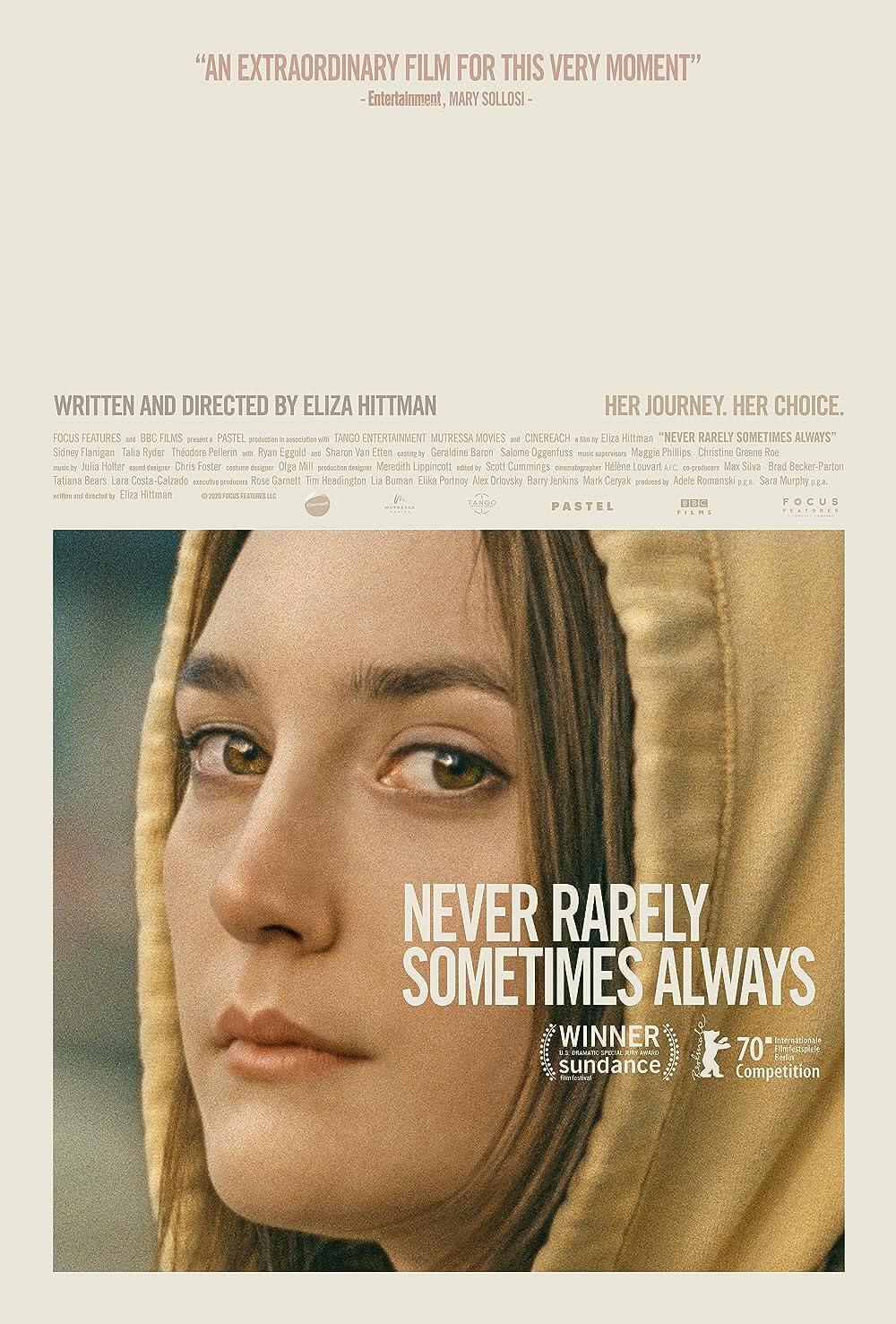

If the film seemed representative of a distant and disturbing past in 2007, the rise of ultra-right-wing governments and fascistic leaders today threatens to recreate the world that Mungiu depicts. Acquiring an abortion in the United States, for instance, has become a challenge—to the extent that the 2020 film Never Rarely Sometimes Always, about a teenager who must travel across state lines to find a clinic that will perform an abortion without notifying her parents, has been heralded as an achingly real reflection of contemporary life. The character, named Autumn and played by first-time performer Sidney Flanigan, learns that she is 18 weeks pregnant, just a week shy of Gabita’s pregnancy referenced by the title. Similar to Gabita, Autumn is accompanied by her close friend who, like Otilia, deals with practical matters better than her pregnant friend. It’s even shot in a similar realist style by director Eliza Hittman, except the story takes place in present-day America. In the world of Mungiu’s film, countless women lost their lives to illegal back-alley procedures that led to post-abortion distress. Fortunately, Mungiu avoids turning 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days into a mere polemic that reflects contemporary society and fosters germane conversations. It’s not an allegory nor an argument for Pro-Choice or Pro-Life—though it could be interpreted from either perspective, given its image of an aborted fetus that cannot help but spark a visceral gut reaction, regardless of how the act itself has been politicized.

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days uncovers the consequences of a state authority that has enough power to control the most private spaces of human life. Mungiu critiques how policy in Communist Romania extended from personal freedoms to women’s bodies and beyond, often to desperate and dehumanizing effect. However specific and realistic it may seem, the film is brilliantly careful about its method of storytelling as well, making the story feel urgent even outside of its Romanian context. Mungiu’s characters never use the Soviet familiar “comrade” or make any reference to Ceaușescu, nor does Mungiu speak down to the audience by clarifying the historical context beyond establishing the country and year. There’s no brief history of Romania or Decree 770 either. Nevertheless, the film’s fish tank quality forces the audience to consider two worlds, the one onscreen and our own. The motif is suggested once more in the final, unmoving shot of Otilia and Gabita in the hotel restaurant. All at once, headlights from passing cars reflect against a window, and we realize that the shot comes from behind a pane of glass. “We’re never going to talk about this, okay?” Otilia tells Gabita. The two friends remain on display, ever visible and closely monitored subjects of the oppressive state.

Bibliography:

Cazan, Roxana. “Constructing Spaces of Dissent in Communist Romania: Ruined Bodies and Clandestine Spaces in Cristian Mungiu’s ‘4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days’ and Gabriela Adamesteanu’s ‘A Few Days in the Hospital.’” Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 39, no. 3/4, 2011, pp. 93–112. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41308346. Accessed 29 April 2020.

Jones, Kristin M. “4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days.” Film Comment, vol. 44, no. 1, 2008, pp. 69–70. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43458901. Accessed 1 May 2020.

Nasta, Dominique. Contemporary Romanian Cinema: The History of an Unexpected Miracle. Columbia University Press, 2013.

Taylor, Ella. “4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days: Late Term.” Criterion.com. 25 Jan. 2019. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/6166-4-months-3-weeks-and-2-days-late-term. Accessed 18 May 2020.

Uricaru, Ioana. “4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days: The Corruption of Intimacy.” Film Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 4, 2008, pp. 12–17. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2008.61.4.12. Accessed 1 May 2020.

Wilson, Emma. “4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days: An ‘Abortion Movie’?” Film Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 4, 2008, pp. 18–23. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2008.61.4.18. Accessed 29 April 2020.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review