The Definitives

28 Days Later (2002)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

28 Days Later exposes the impotence of our institutions, both social and administrative, with the bleak realization that people are not as well safeguarded from danger as they believe. The film is a reflection of the crisis mentality felt throughout Western culture in the wake of 9/11, though it was written before the historic attack and released in its aftermath. It warns that our civilization teeter-totters on the brink of chaos and oblivion, drawing from a recent past and signaling to a dreaded future. Danny Boyle’s 2002 film is a zombie reinvention, introducing a fast-paced alternative that, in its frantic speed and unrelenting savagery, better symbolizes people’s innate fear of society’s collapse and of losing oneself to the inhumanity of fury and violence. It is also an urgent genre innovation, building on established tropes to capture the new heights of accelerated violence and paranoia that pulse through the veins of the twenty-first century. Boyle’s film addresses our inability to maintain control in an accelerated world, where the infrastructure’s fluidity and vulnerability has resulted in insecurity, doubt, and despair over its failure. 28 Days Later manifests these social and institutional anxieties into a virus, an unseen threat in the form of an invasive metaphor. The resulting apocalypse and disintegration of all that is familiar and safe, dramatized in the film with great symbolic effect, contains a foreboding toward the modern world that continues to resonate with every viewing.

In his essay “9/11 and the Wasted Lives of Posthuman Zombies,” Lars Schmeink observes that popular culture’s way of dealing with post-9/11 tensions was “rich in critique of the social realities that led to the attacks and/or followed them, as well as rich in negotiations of the feelings of despair, apocalypse, and helplessness.” The attacks on the Pentagon and World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, were the catalyst for a new form of globalization from which no one could escape. In the aftermath, the rhetoric used by President George W. Bush to launch an “international coalition against terror” volunteered the rest of the world to take part in the United States’ grief and desire for vengeance. No longer could someone cut themselves off from the world. No longer were there safe spaces to which one could escape. Life suddenly became unpredictable, unreliable, and insecure—a condition that was not exclusive to the U.S. but felt everywhere on the planet. The world had become an all-penetrating force, resulting in waves of increasing paranoia about the threat of terrorism, war, or environmental disaster, and from them, the lingering threat of an apocalypse that could occur at any moment. Films and television shows negotiated these anxieties with hundreds of stories about the apocalypse, post-nuclear wastelands, alien invasions, bioterrorism, and massive pandemics. And while such stories were explored prior to 9/11, they became omnipresent in the cultural consciousness after 2001. Above all others, the zombie film remains the most popular example of humanity processing its uncertainty and innate fear of humanity’s violent limits and faulty infrastructure.

28 Days Later reveals how the Western world no longer felt safe and secure, and how perhaps that security was always an illusion. Whether by intention or convenient timing, the film exploits post-9/11 anxieties felt by the newly globalized world, using a genre that had been largely absent from cinemas for more than a decade—the zombie film, which often uses reanimated corpses to symbolize how human beings were the greatest threat to humanity. Zombie films reached a minor zenith in the 1980s, with examples ranging from George A. Romero’s bitter Day of the Dead (1985) to the comically self-aware The Return of the Living Dead (1985), along with countless others. At the same time in Europe, filmmakers such as Lucio Fulci (City of the Living Dead, 1980), Bruno Mattei (Hell of the Living Dead, 1980), and Jean Rollin (Zombie Lake, 1981) built upon Romero’s formative examples of Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978) by testing the limits of gore and exploitation. In the U.S., zombies also became a source of horror-comedy in the 1980s, and directors Stuart Gordon (Re-Animator, 1985) and Fred Dekker (Night of the Creeps, 1986) used them to explore the genre for cult audiences primed for a grim laugh. By the 1990s, the zombie film had all but disappeared along with the heyday of gory practical make-up effects of the 1980s, with just a few zombie titles appearing in theaters throughout the decade. But like zombies so often do in films, the genre returned to life following a major disaster.

After 9/11, 28 Days Later, released in November of 2002, launched a renewed interest in the post-apocalyptic zombie film. When its last-man-on-Earth protagonist wanders through the empty streets of London, the images captured on grainy handheld digital video, it could not help but recall the devastating scenes of the Twin Towers falling and the eerily vacant city streets shot by witnesses and the media. To a much lesser extent, Paul W.S. Anderson’s popular Resident Evil, also released in 2002, contributed to the twenty-first century’s growing obsession with zombies, although the imagery employed in Anderson’s film is derived from the Capcom video game series on which it was based. Given the financial successes of these two films, many others followed. In 2004, Zack Snyder’s remake Dawn of the Dead and Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Dead both earned a bundle, and their nostalgic references to zombie films of the past ensured that audiences would want to (re)discover zombie titles from decades prior, while also creating a market for new zombie material. Romero, the father of the modern zombie, who since the 1980s had been relegated into obscurity, was now considered bankable again. He returned with new offerings: Land of the Dead (2005), Diary of the Dead (2007), and Survival of the Dead (2009). In 2010, the AMC network developed a graphic novel series into the enormously popular television show The Walking Dead, bringing post-apocalyptic themes and bloody zombie violence into the homes of millions of basic cable subscribers. The examples of zombie films and programming continued in the ensuing years with zombie-themed comedies (Zombieland, 2009), blockbusters (World War Z, 2013), young adult fiction (Warm Bodies, 2013), satires (Juan of the Dead, 2011), romantic comedies (Burying the Ex, 2014), and even family films (ParaNorman, 2012).

28 Days Later was conceived well before 9/11, though its prescient ideas anticipated many of the same feelings experienced by Western culture in the wake of the attacks. The production went into principal photography on September 1, 2001, and its writer, Alex Garland, had been inspired by events that nonetheless spoke to similar anxieties as those felt in the post-9/11 period. Garland, ever interested in the zombie genre, hoped to revive the material for a new generation by drawing from the headlines and remarking on social conflict and our loss of patience for other human beings. His apocalyptic imagery was inspired by an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease throughout the United Kingdom in 2001 that resulted in cows being slaughtered by the millions in order to contain the epidemic. Boyle, who had very little knowledge of zombie cinema, told IndieWire in 2003 that the absence of livestock on the countryside felt catastrophic and ominous: “If you took a train journey, everything was still and motionless outside the train or outside your car.” Garland also drew from images of people looking at walls of “missing” posters that emerged after a devastating earthquake in China. To be sure, the most frightening ideas in 28 Days Later have little to do with its innovative take on zombies; they isolate us by exposing the inability of our institutions (government, emergency services, military) to protect us when something truly horrific like an outbreak, natural disaster, or terrorist attack occurs. In the aftermath of 9/11, the filmmakers transformed the impetus of 28 Days Later by augmenting their commentary on social rage with our feelings of vulnerability to an apocalyptic event, and our certainty that not even our impressive cities or governmental infrastructure could protect us.

The key to the effectiveness of 28 Days Later is how it reflects modern culture in myriad ways, remarking on persistent fears of other people and cultures, our institutions, our sense of safety, and the perceived threats around us. Consider the origin of the zombies in the film. Years of news stories and fiction about genetic engineering and viral outbreaks led to anxieties about a corporate entity concocting the apocalypse in a lab. Reports of bio-weapons, such as strains of anthrax, used throughout the twentieth century by various countries—for instance, a strain engineered by the Soviet Union during the Cold War—implanted this fear, which returned after 9/11 with a string anthrax attacks. Bioterrorism was a persistent fear in the post-9/11 consciousness, and the opening scenes in 28 Days Later anticipate the concern that humanity would author its own demise. In the first scenes, animal rights activists break into a Cambridge primate research lab to liberate chimps used in testing. In addition to apes locked in small cages, they discover one animal strapped to a table and fed a stream of televised media violence. The attending scientist (David Schneider) tries to talk the activists out of their decision, suggesting the animals have been infected with “rage”—a condition of humanity that threatens the entire species and which the scientists hope to cure. When the activists ignore the scientist’s warning that the chimps carry an infection in the blood, they free an animal only to become the victims of an attack. Within seconds, the chimp has bitten its liberator, who then proceeds to vomit streams of bloody infection and transform into a red-eyed rage monster, albeit human. In a way, the institution has created the very apocalypse it sought to prevent.

Earlier films have introduced the zombie apocalypse by sometimes fantastical means: space rays, fallen satellites, radiation, magic, toxic gases, and experiments-gone-wrong have all brought the dead back to life. Each incitation has the same outcome: corpses suddenly begin to reanimate and have an all-consuming hunger for flesh, usually human. However, 28 Days Later is not a zombie film in the traditional sense. Its rage-infected crowds have not died and come back to life; they are living, breathing human beings changed by a bio-engineered virus and, therefore, are more human than not. Most representations of pre-9/11 zombies derive from Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, with its sluggish ghouls that emerge from the grave to eat the flesh of the living. 28 Days Later is more of a contagion film that resembles a zombie film, in that its zombies are not interested in a human meal; rather, they have been infected with a disease. When the so-called Infected attack, they scratch, bite, pummel, and kill. Their teeth are weapons, but they do not consume their victims. And unlike slow zombies, the Infected can maneuver through barricades and run up staircases. They attack because it is the unconscious hatred, mistrust, and fear of humanity that drives them.

At one point, a survivor encounters an infected boy who, through his hideous, guttural screams, snarls “I hate you!”—and so some fragment of self must remain in the Infected. The virus has accelerated the interior rage of human beings, turning them from the plodding drones of yesterday’s zombie film into the hyperactive and alert bodies of the fast-paced modern world. These are not Romero’s slogging, limping zombies that only prove to be a threat in vast numbers, nor are they the faster-moving zombies in The Return of the Living Dead that rush toward a fresh brain. The rage of the Infected has made them amped-up, hyper-violent, as though every drop from their adrenal gland had been squeezed into their veins. Boyle even insisted that the production use athletes to portray the intensity of the Infected, ensuring their bodies would capture the physical tension and power implied by the film’s theme. And whereas a Romero zombie bite might take hours or even days to result in another undead, the rage virus has an incubation period of seconds. A single Infected is just as dangerous as a suicide bomber; unleash one in a crowd and hundreds will succumb in an instant. Romero used zombies to symbolize social conditions from racism to consumerism, but the fast-moving Infected of 28 Days Later represent a complete loss of control—a corrosion of the social artifice, which was constructed by institutional and cultural learning, to reveal the animalistic monster that lurks inside of every human being.

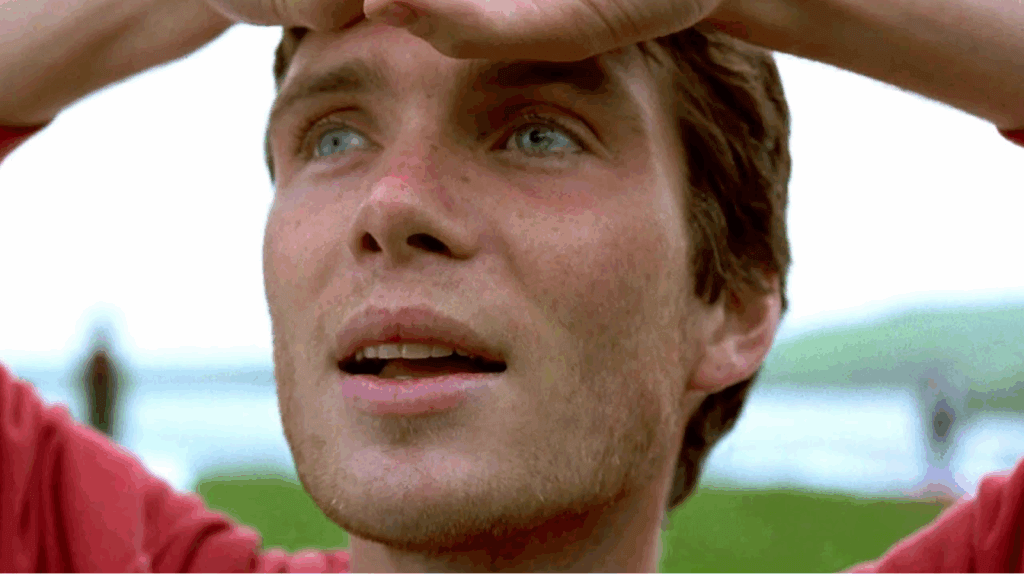

Although its intensified version of the zombie heightens the film’s terror, 28 Days Later begins by preying on the blind faith people have in their institutions and their illusory sense of security with an initial last-man-on-Earth scenario. The story begins with a bike courier named Jim (Cillian Murphy) who awakens from a coma several weeks after an epidemic of the rage virus has left Britain in shambles. Rail thin and unsure of what’s happening, he wakes up in a hospital bed naked, a blank slate of a human being. He dresses in some hospital garb and goes out to find London disturbingly motionless, abandoned. The city is a void. He sees no evidence of social order anywhere—no police, military, or communities of people. He finds vague traces of what has occurred in a discarded newspaper that reads “Evacuation” and tells of a “Mass Exodus” out of the country. Searching for some order to the universe in which he has awoken, Jim enters a church, where he has his first encounter with a hissing, twitching member of the Infected: a priest, whom Jim must strike down to avoid being attacked. His government has proven obsolete, and his religious convictions have betrayed him. Jim can do nothing else but run. If not for being rescued by other survivors, he would have surely succumbed to the complete collapse of society.

Jim’s isolation is furthered when he sees the extent to which the virus has not only rendered the government obsolete, but how it has turned people on one another. After two hardened survivors, Selena (Naomie Harris) and Mark (Noah Huntley), rescue Jim, they explain how the virus works—anyone can become one of the Infected from a drop of blood or saliva. Jim expresses some faith that the government must exist and be able to provide help. “There’s no government,” Selena remarks. “Of course there’s a government,” Jim replies, a twinge of desperation in his voice. “There’s always a government.” But the film’s situation demonstrates that, if there is a government, it has gloriously failed Jim and his fellow survivors. Later, while visiting his home with Selena and Mark, where he finds that his parents committed suicide during the initial outbreak, Jim sees how quickly the virus works and how it has revealed the speed at which human beings will turn on one another. Due to Jim lighting a candle at night, his former neighbors, now Infected, crash through the windows and attack. During the siege, Mark is bitten. Mark looks at Selena, terrified because he knows he is infected and he knows how Selena will react. She chops into Mark with a machete just as she would one of the Infected, hacking away in violent, disturbing blows. As Schmeink notes, Selena’s reaction is tantamount to America’s “War on Terror” after 9/11—an action that is at least equal to the barbarity of the attack. And like America’s stance on terrorism, Selena is not afraid to act first to prevent future violence. It’s a logic that, through the course of the film, proves to be Selena’s central flaw.

When it was released in 2002, 28 Days Later seemed to manifest feelings of mistrust toward the U.S. government that failed to prevent and, in a roundabout way, even contributed to 9/11, while also exploiting the paranoia that anyone could be radicalized into committing a terrorist act. The 9/11 attacks were coordinated by Osama bin Laden, who had allegedly received funding and training during Operation Cyclone, the CIA’s initiative to fund and arm the mujahideen in Afghanistan between 1979 to 1989, which was part of a greater effort to combat the USSR’s spread into the territory that would threaten the supply of oil to America. If 9/11 is the plan of Osama bin Laden, who is a result of America’s foreign policy during the 1980s, then the country bears some degree of responsibility for creating the very thing that attacked it. Similarly, the virus in 28 Days Later is not the product of a terrorist attack; it was engineered in a lab by British scientists and unleashed on accident by social activists. This line of thinking is not designed to link activists with terrorists; rather, it underscores that some measure of responsibility lies with the institutions established to safeguard people when their choices ultimately do harm. Additionally, after 9/11, news stories about American citizens, from John Walker Lindh joining the Taliban to several individuals joining ISIS, spread the fear that your friends or neighbors could be or easily become extremists, leading to rampant paranoia. It is a similar loss of faith in government and mistrust of one’s fellow citizen that permeated the post-9/11 era and isolates Jim, who still has faith in the government and other people for much of 28 Days Later.

The film’s mistrust of governmental institutions and their promise of protection and civilization shapes the third act, which finds Jim, Selena, and the father-daughter pair of Frank (Brendan Gleeson) and Hannah (Megan Burns), driving together toward a military radio broadcast that promises, “The answer to infection.” The characters of 28 Days Later are, to some extent, defined by their level of faith in civilization. Frank is optimistic, perhaps because he has to maintain hope that his teenage daughter Hannah has a future. Jim shares Frank’s perspective, trusting in institutions from the government to the family unit. But Selena has the opposite view; she has accepted disorder. “Plans are pointless,” she says. “Staying alive is as good as it gets.” She watched as civilization’s infrastructure crumbled and her loved ones became infected during the initial rage virus outbreak. Now she hesitates to put her trust in anyone or anything. For that reason, she resists what becomes an inevitable romantic relationship with Jim. When the survivors reach the military outpost and discover it abandoned, Frank loses hope and gives in to his anger. His momentary rage is answered when he shouts at a raven pecking at a corpse from a high perch, and then a single droplet of blood lands in his eye. Frank becomes one of the Infected in a scene that shows how quickly a loved one can become an inhuman monster. Selena screams for Jim to kill the Infected Frank, but Jim cannot. Almost immediately, soldiers off-screen shoot him down, and then quickly guide Jim, Selena, and Hannah into their vehicles, back to their well-protected makeshift headquarters established on a country estate.

The theme of civilization’s fragility lies at the center of 28 Days Later. Civilization is a security blanket that deflects chaos, and when pulled over the eyes, the blanket also serves as a blinder to the disorder of the universe—the frightening reality that human beings can be violent animals and are not some elevated species made in the image of their omniscient god. The rage virus has torn holes in the fabric of that blanket, and the military men left behind in the film desperately cling to its memory. They want to patch it, but they are lousy seamsters. Led by Major Henry West (Christopher Eccleston), the all-male soldiers have amenities that other survivors do not: food, hot water, weapons, and clean beds—tools of civilization that lack the human components of empathy, creativity, or the thirst for knowledge. They have decided that furthering the species is their only hope of restoring what they consider to be civilization. “I promised them women,” admits West in a chilling confession that dooms Selena and Hannah into sexual slavery. The trip to discover the last sign of civilization reveals that civilization has not just utterly collapsed, has not just proved unprepared to protect society from the rampant spread of disease and violence, but it has always been savagely violent. The soldiers’ answer to infection is their warped view of civilization, but they are no more civilized than post-apocalyptic raiders from The Road Warrior (1982) or The Road (2011). And when Jim fights back against their plan, they set him for execution.

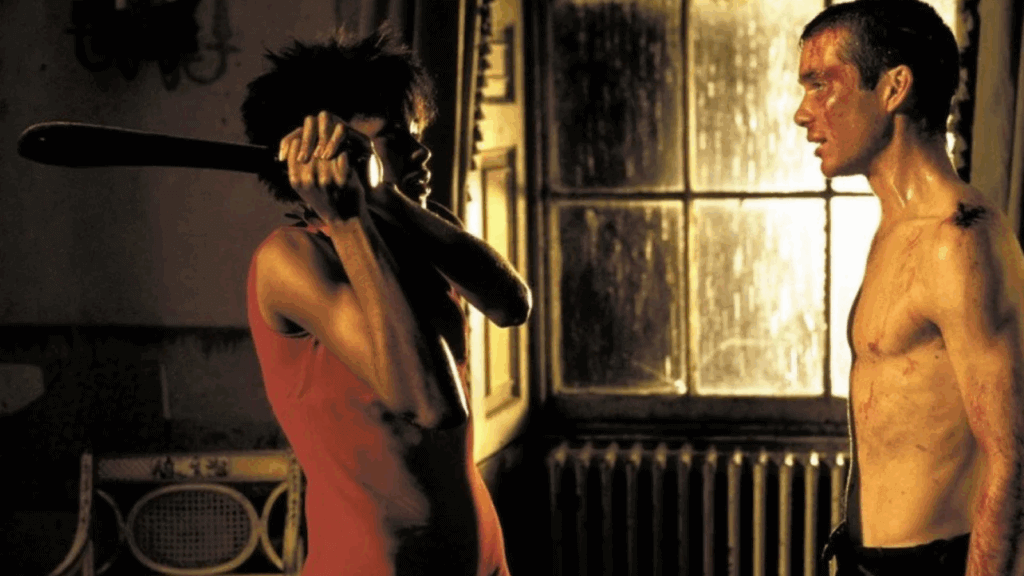

Jim’s arc in 28 Days Later brings him to the brink of chaos, to the limits of humanity’s ferocious capacity for violence, and back again. It is a trajectory experienced by Selena, who has already reached her limit when she is first introduced, though she eventually comes to trust Jim, Frank, and Hannah in feelings that allay her initial savagery. Whereas before she cared only about ensuring her own survival, she now protects Hannah from the soldiers with sisterly concern. Jim, having slept through the worst parts of the outbreak, has not survived by killing as Selena has. The first Infected he kills is a small boy on the road to the military outpost, and later he hesitates when Frank begins to turn. Jim is only activated on his journey toward uncivilized violence out of the primal need to protect his new family—a need in which he could lose himself. Jim and Selena, then, pass each other on opposite trajectories toward and away from the violence of an uncivilized world. With the soldiers shattering Jim’s faith that the government is a beacon of salvation, he escapes his execution and returns to the estate where Selena and Hannah are being prepared for summary rape and impregnation. He uses the Infected to cause distractions and attack the soldiers, while at the same time resorting to eye-gouging violence himself. Every muscle in his body becomes sinuous, recalling one of the Infected. One by one, he kills the soldiers, until he finds Selena. When they first met, Selena told Jim that she would not hesitate to kill him if he were infected. But when she sees Jim in his primal state—he’s covered in the blood of soldiers and uncharacteristically aggressive, and she assumes he is Infected—she hesitates and cannot attack him. Their roles have reversed and, now having experienced the same journey toward violence and back again, they embrace.

28 Days Later asks the question: What is civilization? The hopeless soldiers define it by infrastructure and the propagation of the species. One of the essential plot points of the film is when Major West observes that the Infected could not build the infrastructure or agricultural resources required to survive, and therefore they would soon disappear from starvation. It was only a question of how long. After they are gone, the remaining people could rebuild. But the film suggests that infrastructure is not enough; it is the human capacity for empathy that makes humanity civilized. In the final scenes, we find Jim, Selena, and Hannah living in a secluded house in the countryside. Having rid themselves of the soldiers, they wait for the Infected population to starve out of existence. Returning for a moment to the idea of civilization as a security blanket that protects humanity, we also see Selena sewing together bedsheets and curtains in the form of letters. In the distance, the survivors hear the sound of an approaching jet, a sign of the infrastructure that has apparently survived the rage virus. They rush out to a hillside, where they unfurl a message to the jet, spelled out using cloth letters. Their signal is not “SOS” or “HELP” but “HELLO”—a friendly greeting rather than a desperate plea for rescue or a statement of dependence. Selena has sewn a gesture of kindness, a symbol of a society rooted in human connections rather than a civilization of unreliable institutions.

Boyle mirrors the film’s remarks about civilization with his form-follows-function approach to 28 Days Later. The production, financed independently on a budget of $8 million, shot guerilla-style on the streets of London and elsewhere around England, sometimes without permits. Boyle thrives under seemingly impossible filming conditions, whether it’s making the ultra-low-budget Shallow Grave (1994) or traveling to Mumbai to shoot Slumdog Millionaire (2008) under harsh conditions. With 28 Days Later, Boyle’s necessity for invention to cut costs and shoot fast led to his dynamic use of inexpensive digital video. In the early 2000s, digital video was rarely used and considered an unproven format. Though easier to use than film stock, it presented a fuzzy and unstable image. Only Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2000), Richard Linklater’s Tape (2001), and a few other rare titles effectively employed DV for theatrical exhibition—and often only because the grainy nature of the format aligned with the screen story. Cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle’s largely handheld DV camerawork gives the film its distinct, pixelated appearance, while also reflecting the apocalyptic situation with an almost found-footage quality. Whereas earlier zombie films capture the slow-moving zombie in long, staid shots to match the slowness of the undead, Boyle’s digital sensibilities better symbolize the frenzied quality of the Infected and the chaos of the post-apocalyptic setting. However, the last sequence on the countryside is shot in 35mm and diverts from the rest of the film. This implies through its formal clarity that the chaos has ended and some manner of calm has been restored.

28 Days Later captures how the infrastructure and social order designed to protect humanity create illusions of safety, a notion furthered in the post-9/11 world of increased paranoia and uncertainty. Its images of an empty, post-apocalyptic world, epitomized by Jim’s haunting and iconic walk across the abandoned Westminster Bridge, reflect the era’s overwhelming isolation. But it’s a world populated by the violent remnants of humanity, preying on the audience’s lingering suspicion of anyone and everyone. The era’s shattered sense of security and distrust in others represents the failure of civilization and, as evidenced in the dramatic arcs of both Jim and Selena, the potential loss of self and humanity to rage and violence. Even so, the film sees an opportunity to grow an alternative form of civilization that relies less on institutions and more on each other. It is a hopeful idea that has not yet come to pass. Ironically, in the subsequent two decades after 9/11 exposed our inadequate institutions, humanity has moved toward another state of blind reliance on increasingly nationalistic governments who once again promise to protect their citizens from outside dangers, which the institutions may have created or fabricated. Boyle’s film, once a mirror of post-9/11 anxieties, now negotiates our present culture of rage, intolerance, and false sense of security by dramatizing a horrific breakdown of civilization. In reflecting our world, he film is scarier than ever.

Bibliography:

Page, Edwin. Ordinary Heroes: The Films of Danny Boyle. Empiricus Books, 2010.

Raphael, Amy. Danny Boyle: In His Own Words. Faber & Faber, 2010.

Roy, Arundhati Roy. “The algebra of infinite justice.” The Guardian. 29 September 2001. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/sep/29/september11.afghanistan

Russell, Jamie. Book of the Dead. FAB Press, 2005.

Schmeink, Lars. “9/11 and the Wasted Lives of Posthuman Zombies.” Biopunk Dystopias: Genetic Engineering, Society and Science Fiction. Liverpool University Press, 2016, pp. 200-236.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review