The Definitives

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey does not require audiences to follow a story realized with dramatic character arcs and a traditional narrative structure, but rather it compels an elusive sensory and cognitive experience to inspire contemplation of its meaning. The film resonates with wonder, unparalleled before or since its release in 1968, as opposed to a preoccupation with entertainment value or turns of the plot. Like a fine piece of music, the motion picture’s chords and harmony must be felt in all their intangibility to be appreciated. By reducing the importance of the story, Kubrick forces concentration on the purely aesthetic elements and their integration with the existential, evolutionary, and revolutionary journey detailed in the film. How appropriate that a majority of film’s events unfold in the uncertainty of space because in this abstract and elusive realm of the unknown, Kubrick can involve the viewer and achieve understanding through feeling, and therein avoid the schematics of traditional storytelling.

Episodic in configuration, the film employs chapters marking what are commonly interpreted as significant developments in human intelligence, expanding from prehistory to the year 2001, and then escalating beyond time and space. In determining how these individual chapters correlate to one another endures an omnipresent mystery and the basis of an ongoing fascination with the film. Some have argued that together the chapters put forward a quest to find God, or an allegory for the cycle of birth-life-death-rebirth. After comprising his first cut, the director edited down the footage and removed explanatory narration from the opening sequence to instill doubt about the subsequent events. To be sure, ambiguity was Kubrick’s intention. In a 1968 interview with Playboy magazine, Kubrick stated, “You’re free to speculate as you wish about the philosophical and allegorical meaning of the film [but] I don’t want to spell out a verbal road map for 2001 that every viewer will feel obligated to pursue or else fear he’s missed the point.”

Conceived in partnership with Arthur C. Clarke, author of the novel written in conceptual union with Kubrick’s production, the film and book complement each other in their individual ways. Whereas Clarke fleshes-out the film’s intended elusiveness, Kubrick’s realization of his screenplay reaches the audience in ways not possible for a book, sending viewers on a journey no literary arrangement of words could manage. Even the title’s Homeric reference to The Odyssey underlines how the film’s journey and the trademarks therein take precedence over where the journey ends. No protagonist exists through which the audience can follow a traditional story arc, and what characters there are dissolve into their backdrops. Not even dialogue has a place within the picture for the first thirty minutes, and those few spoken lines in the remainder bear little consequence to the film’s meaning. Kubrick has ostensibly made a silent film that requires sensations to guide its implications.

Conceived in partnership with Arthur C. Clarke, author of the novel written in conceptual union with Kubrick’s production, the film and book complement each other in their individual ways. Whereas Clarke fleshes-out the film’s intended elusiveness, Kubrick’s realization of his screenplay reaches the audience in ways not possible for a book, sending viewers on a journey no literary arrangement of words could manage. Even the title’s Homeric reference to The Odyssey underlines how the film’s journey and the trademarks therein take precedence over where the journey ends. No protagonist exists through which the audience can follow a traditional story arc, and what characters there are dissolve into their backdrops. Not even dialogue has a place within the picture for the first thirty minutes, and those few spoken lines in the remainder bear little consequence to the film’s meaning. Kubrick has ostensibly made a silent film that requires sensations to guide its implications.

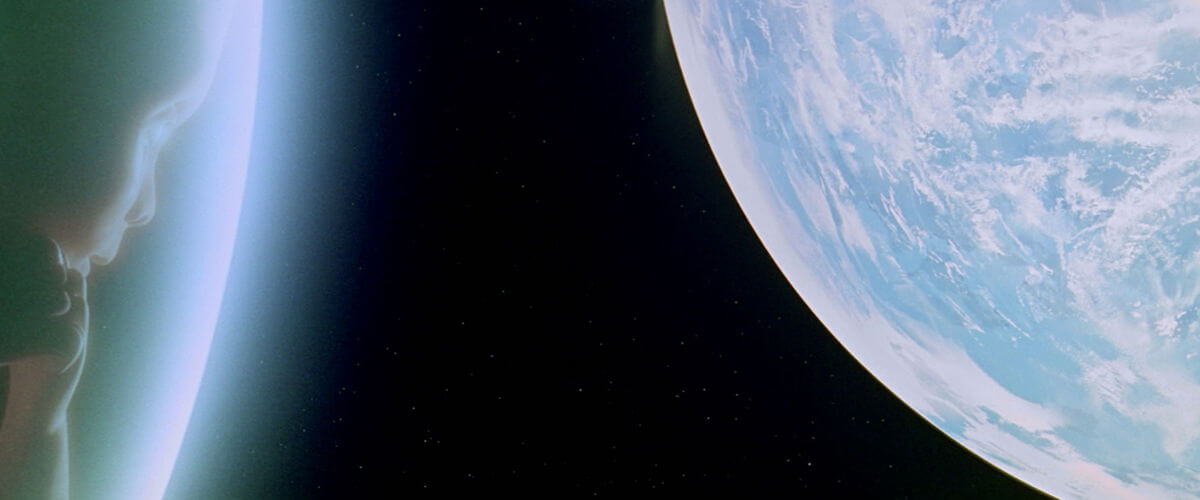

Those sensations imply that the spartan plot details the progression of human intelligence guided by a specific positioning of the stellar phenomenon, as well as another astral force, most likely extra-terrestrial, presented in the form of the iconic black rectangular Monolith. The first frames show the alignment of the Sun, Earth, and Moon, and then fall upon our young planet where apelike creatures gather in clans and fight over a nearby watering hole. Perhaps these creatures are the missing link between man and ape, as they are not yet “Kings of the Jungle”—a resident leopard sits on high and pounces on them when ready. Covered in black hair, these simple omnivores spend their days digging for worms and picking at plants. The realism of the apes is astounding and suggests an original species without a moment wasted thinking of how actors inhabit costumes (nothing like the outfits donned in Planet of the Apes, also released in 1968). One morning, the Monolith appears embedded into the ground facing the weaker clan. At first, there is fear, then comes gentle, dumbfounded caresses, and soon a notion of comprehension. Later, one of them discovers how easily a leftover bone becomes a weapon, a thought discernibly guided by the Monolith. The ape can now hunt, kill off the competition, and rule the watering hole with its discovery. The segment’s opening title labels this “The Dawn of Man.”

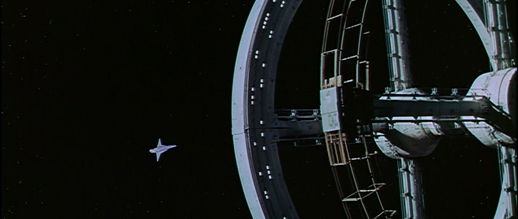

Transitioning from the operative use of a blunt object to the analogous instrumentality of a spacecraft, the film jumps into the future, where a transport docks at a station orbiting Earth. Onboard, Dr. Heywood R. Floyd (William Sylvester) visits moon base Clavius where a virus quarantine cover-up story hides his operation’s discovery of a Monolith, deliberately buried on the moon some 4 million years ago. Kubrick establishes his futuristic setting in these scenes, taking his time to demonstrate the rules of weightlessness, zero-gravity food and toilets, and advances in spaceship technologies. When Heywood’s crew arrives on the lunar surface to study the Monolith, a deafening tone sounds, to be identified later as a radio emission aimed at Jupiter. Throughout the film, Kubrick incorporates extended sequences, wherein spaceships ease into their docking bays or attendants carry out intricate technical procedures, to emphasize the necessity of viewer perception. And so, the film often receives criticism for its methodical pace. But with Kubrick’s calculated tempo, he allows the viewer to meditate over why the film itself broods on its imagery. An experience harbored in metaphysical symmetry felt through recurring images, namely the Monolith and the “mystical” alignment of the Sun, Moon, and Earth, watching the film and reflecting on such signs and their meaning identifies the film’s apparent linking of animal, man, and machine, and then underscores how those limitations are eventually transcended.

Consider the music, which, comprised of selections from Johann Strauss’ The Blue Danube, does not underscore and emphasize the depicted actions, but rather enlivens the proceedings through unparalleled amplitude. Kubrick initially commissioned Alex North to compose a score, which despite not being used for the film, still earns praise as a work of some accomplishment (North’s score is readily available for purchase as an alternate soundtrack). Where prerecorded Strauss overcomes is the music’s ability to create awe around the sights onscreen. The waltz dances around a twirling spacecraft and ruminates on a floating pen as if both were glorious events outside comprehension. And consider the specific use of Richard Strauss’ “Thus Spake Zarathustra” in crucial moments of the film’s developing thesis, particularly shots of the alignment and Monolith. Five key notes followed by a reverberating drum work toward building unparalleled magnificence, the realization of which is almost prophetic and certainly extraordinary in its formation. The piece will be forever associated with existential ceremony, Kubrick’s motion picture, and countless references to the picture’s essence of grandeur. Whereas traditional movie scores punctuate and even instruct how we should feel about a given scene, Kubrick’s ethereal selections leave us pondering his film in reverence and deep contemplation.

Consider the music, which, comprised of selections from Johann Strauss’ The Blue Danube, does not underscore and emphasize the depicted actions, but rather enlivens the proceedings through unparalleled amplitude. Kubrick initially commissioned Alex North to compose a score, which despite not being used for the film, still earns praise as a work of some accomplishment (North’s score is readily available for purchase as an alternate soundtrack). Where prerecorded Strauss overcomes is the music’s ability to create awe around the sights onscreen. The waltz dances around a twirling spacecraft and ruminates on a floating pen as if both were glorious events outside comprehension. And consider the specific use of Richard Strauss’ “Thus Spake Zarathustra” in crucial moments of the film’s developing thesis, particularly shots of the alignment and Monolith. Five key notes followed by a reverberating drum work toward building unparalleled magnificence, the realization of which is almost prophetic and certainly extraordinary in its formation. The piece will be forever associated with existential ceremony, Kubrick’s motion picture, and countless references to the picture’s essence of grandeur. Whereas traditional movie scores punctuate and even instruct how we should feel about a given scene, Kubrick’s ethereal selections leave us pondering his film in reverence and deep contemplation.

Supporting his intended awe, Kubrick exercises unparalleled precision and imagination in devising the film’s incredible special effects. The rotating space station, gliding transports, and shuttle pods exist in empty space and avoid any associations with models: no strings, no evident animation, no dated renderings. Today Kubrick’s film boasts more unfathomable special effects than the archetypal space opera Star Wars, which came nearly a decade later and contains model shots nothing short of obvious. (George Lucas’ motion control photography shows the square edges of the frame on film, so his spaceships occasionally appear to be flying in a box through space, thus diminishing the power of his illusion.) Designed before the age of comparably flat CGI, Kubrick’s three-dimensional creations remain so real that today’s animation wizards cannot replicate their tangibility. How exactly Kubrick devised these effects could be and has been documented in much detail, however not knowing retains the film’s mystical quality. Would the sleeping man’s pen, floating weightless beside him only to be recovered by an approaching stewardess, be as visually engaging and technically impressive if the movie magic behind this effect was explained away? Other writers have detailed the hows behind Kubrick’s astounding effects usage, but not knowing adds to the awe-inspiring presentation, so there will be no detailed account here if only to preserve the film’s clarity of purpose.

Though Apollo 11 would not land on the moon for another year, Kubrick’s film envisions futurist ideas about space travel, artificial gravity, cryogenic transportation, but most significantly, the horrible possibilities for artificial intelligence. Eighteen months after the Monolith’s radio emission zoomed toward Jupiter, a five-person mission deploys in that direction, three of them frozen for the trip. Awake are astronauts Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), two staid characters described thinly, without backgrounds or expressions of emotion. The crewmembers, though focused on their tasks, occupy their time drawing, viewing communiqués from home, and exercising in a revolving corridor. Throughout, Kubrick employs disorienting camera positioning to remind the viewer that there is no up or down in space. The emotional detachment in these scenes likens Man to Machine, blurring the lines in their impending conflict to determine if humankind man will destroy itself through its technology.

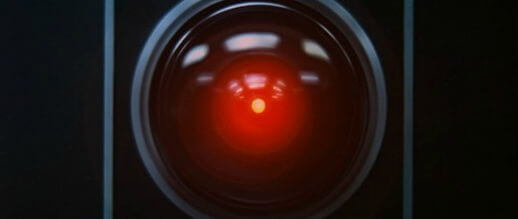

Enter HAL-9000, the non-living embodiment of humankind’s scientific know-how, representing the challenge against which humanity proves whether our technology will destroy us, or whether we have advanced enough as a species to overcome what we create. An amalgam of symbolic fictional monsters from Frankenstein’s creation to the Cyclops from The Odyssey, HAL appears in various terminals throughout the spacecraft as nothing more than a red circular lens gazing outward, controlling every aspect of the ship for its human staff. Given an eerie calm by Douglas Rain, the voice-only performance is perhaps the most potent voicework in all cinema. HAL possesses a flawless programming record, being an infallible computer program that takes pride in its impeccable construction. But does it have consciousness? Dave cannot be sure if real emotions exist behind HAL’s computerized exterior. Undoubtedly, they do. When HAL asks to see Dave’s sketches, he does this because he desires to see them, not out of automaton politeness.

Enter HAL-9000, the non-living embodiment of humankind’s scientific know-how, representing the challenge against which humanity proves whether our technology will destroy us, or whether we have advanced enough as a species to overcome what we create. An amalgam of symbolic fictional monsters from Frankenstein’s creation to the Cyclops from The Odyssey, HAL appears in various terminals throughout the spacecraft as nothing more than a red circular lens gazing outward, controlling every aspect of the ship for its human staff. Given an eerie calm by Douglas Rain, the voice-only performance is perhaps the most potent voicework in all cinema. HAL possesses a flawless programming record, being an infallible computer program that takes pride in its impeccable construction. But does it have consciousness? Dave cannot be sure if real emotions exist behind HAL’s computerized exterior. Undoubtedly, they do. When HAL asks to see Dave’s sketches, he does this because he desires to see them, not out of automaton politeness.

Indeed, Kubrick deliberately gives HAL a more emotive characterization and dialogue than the human crewmembers. Whereas Dave and Frank have virtually no ego, pay attention to HAL’s dialogue when it expresses doubts about the mission, finding it “difficult to put out of my mind.” It sees itself as an individual. Clarke’s novel suggests that because the computer was designed to be so completely accurate, yet its programming requires that it keep the mission’s true nature hidden from the crew until reaching Jupiter, this conflict drives the HAL program insane. It eventually resolves that, after its first error and the humans’ decision to deactivate it as a precaution, the humans threaten the mission’s success and therefore, must be terminated. It turns a shuttle pod on Frank in deep space, sending him flying into nothingness; the cryogenic beds of the frozen crewmembers are sabotaged. During these scenes where HAL launches his attack on the crew, Kubrick makes sure to cut back to the vast emptiness of space, reminding his audience of Dave’s isolation and distance from any form of help.

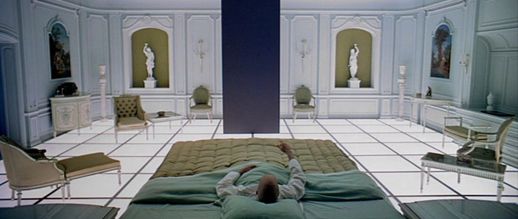

After deactivating HAL, Dave reaches Jupiter to find another astral alignment and Monolith waiting for him. All at once, his pod begins to travel across an endless temporal landscape between two impossibly colored planes of time and space soaring by. Kubrick visually equates the journey to a trek over the Grand Canyon or pulsating ocean. However extended this sequence may be, the trip washes away the previous events in the film and leaves the viewer fresh for what comes next. Dave awakens, his pod set in a room flourishing with decorations straight from, appropriately, The Age of Enlightenment, the quarters containing that same white, antiseptic sheen as a space station. Is Dave an antique, like the artwork and furnishings adorning the room, locked inside what Clarke called an “astral zoo”? Dave witnesses himself aging in a flawless meshing of progressions. It is unclear how long this transformation takes; it could be a matter of minutes or over an expanse of years. He grows older and older until, in the end, the Monolith appears once more at the edge of his bed, and he experiences an all-expansive rebirth of some kind, seemingly transcending time and space. Realized as an intangible, soft-filtered, and slightly transparent ubiquitous baby, this “Star Child” looks down upon his former Earth, having grown beyond its physical crudeness in every way into something more insubstantial. Is the child a God-like figure watching over Earth? Is this ending cynical or hopeful? The figure, no matter how many explanations are offered by viewers and scholars, remains an impenetrable and majestic image.

Though the plot’s broad stokes allow subjective interpretation as to Kubrick’s subject, scholarly analysis dwells too much on the episode involving HAL, because it manifests the most traditionally cinematic and dramatic conflict among the film’s segments. Instead, think about the whole and what this segment means as a piece within the overall design. Technology, the fault of which is exhibited by HAL, provides no solutions other than tools to further propel our species toward a revelatory rebirth. Kubrick suggests that humanity controls its own fate through our slow development into a greater, more evolved, non-physical species. Perhaps his audience is meant to consider how far humanity has to go before reaching any such transcendence, and in that, his film inspires species-scale self-reflection. The Monoliths, then, might be understood as markers or stepping stones, guiding us along the evolutionary ladder by an apparent extra-terrestrial presence, signaling them as to when humanity has readied itself for the next stage of evolution. Aliens supervise and even control via Monolith, positioning the enigmatic forms like preset goals or checkpoints that note the progress of the human race from wild animals to problem solvers, from travelers to the moon to explorers of the entire solar system, from surveyors of open space to inter-dimensional wayfarers voyaging into the existential and non-linear realms. They set breadcrumbs and guide us beyond the need for crude tools like the bone club, the spacecraft, or artificial intelligence, and in the end lay bare where humanity began, and where inevitably it will end up.

Though the plot’s broad stokes allow subjective interpretation as to Kubrick’s subject, scholarly analysis dwells too much on the episode involving HAL, because it manifests the most traditionally cinematic and dramatic conflict among the film’s segments. Instead, think about the whole and what this segment means as a piece within the overall design. Technology, the fault of which is exhibited by HAL, provides no solutions other than tools to further propel our species toward a revelatory rebirth. Kubrick suggests that humanity controls its own fate through our slow development into a greater, more evolved, non-physical species. Perhaps his audience is meant to consider how far humanity has to go before reaching any such transcendence, and in that, his film inspires species-scale self-reflection. The Monoliths, then, might be understood as markers or stepping stones, guiding us along the evolutionary ladder by an apparent extra-terrestrial presence, signaling them as to when humanity has readied itself for the next stage of evolution. Aliens supervise and even control via Monolith, positioning the enigmatic forms like preset goals or checkpoints that note the progress of the human race from wild animals to problem solvers, from travelers to the moon to explorers of the entire solar system, from surveyors of open space to inter-dimensional wayfarers voyaging into the existential and non-linear realms. They set breadcrumbs and guide us beyond the need for crude tools like the bone club, the spacecraft, or artificial intelligence, and in the end lay bare where humanity began, and where inevitably it will end up.

Rather than pursuing the elusive significance behind the images in the film, experience them the way Kubrick intended and devise your own understanding. Though at least one reading is argued above, others are possible and continue to be debated with considerable passion. What prevails is how 2001: A Space Odyssey connects with the viewer, regardless of its ambiguities, and sustains marvel around the film since its release, confirming its place among the greatest films ever made but also making it one of the most unique. Rarely does narrative or linear film communicate its ideas so purely through senses and perceptions, making the medium a conveyance of conceptual signifiers operating to evoke feelings, rather than rational contemplation of a plot. That Kubrick achieved this feat here remains something of a small miracle.

Bibliography:

Chion, Michel. Kubrick’s Cinema Odyssey. British Film Institute, 2001.

LoBrutto, Vincent. Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. D.I. Fine Books, 1997.

Nelson, Thomas Allen. Kubrick, Inside a Film Artist’s Maze. New and expanded ed. Indiana University Press, 2000.

Sperb, Jason. The Kubrick Facade: Faces and Voices in the Films of Stanley Kubrick. Scarecrow Press, 2006.

Philips, Gene D., editor. Stanley Kubrick: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Walker, Alexander, et al. Stanley Kubrick, Director: A Visual Analysis. Rev. and expanded. Norton, 1999.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review