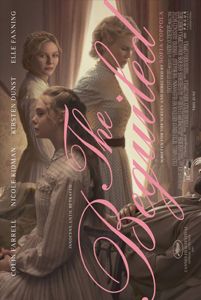

The Beguiled

By Brian Eggert |

The Beguiled is Sofia Coppola’s remake of the 1971 film of the same name. The original was an exploitative oddity, filled with psychosexuality, and starring Clint Eastwood as an injured Union soldier who takes refuge in an all-girls school in the South. Trapped among hysterical vamps and girls desperate for affection, the lurid male fantasy turns into a nightmare when, all of them, including Eastwood’s duplicitous scoundrel, betray and use one another to fulfill their own desires. Laden with deranged dream sequences, hints of incests and other sexual perversities, and a decided sense that everyone onscreen is either repressed, depraved, or downright crazy (or just close to it), director Don Seigel’s film was provocative and unforgettable, if not something of a mess. Nevertheless, it’s a lively piece of 1970s cinema that makes Coppola’s rehash seem undercooked and stripped of everything that made its predecessor an abject entertainment. By contrast, Coppola’s film values restraint over sensuality, suppressing nearly everything that made both Thomas Cullinan’s 1966 source novel and Seigel’s 1971 film entertaining. In doing so, Coppola sort of misses the point and, ironically enough, castrates the material.

Colin Farrell stars as Corporal John McBurney, who’s found by the young Amy (Oona Laurence) on her regular mushroom-picking journey in the woods. Amy does “the Christian thing” and returns McBurney to Miss Farnsworth’s Seminary for Young Ladies, where his wounded leg is stitched by the headmistress, Martha (Nicole Kidman), and her assistant Edwina (Kirsten Dunst). Besides a scene in which Martha gives the unconscious McBurney a sponge bath and cannot help but wonder what’s under the carefully placed loincloth, the eroticism is mostly tempered. The school’s other students—Alicia (Elle Fanning), Jane (Angourie Rice), Emily (Emma Howard), and Marie (Addison Riecke)—interact with McBurney, and he charms them, though Amy seems most taken. (Then again, Alicia, a teen flirt, asks McBurney if he likes apple pie with a suggestive smile.) But McBurney is not the brash, outright manwhore of Eastwood’s version, nor are his motivations clear. He seems to be a coward and deserter. Farrell’s take on McBurney operates at once in less obvious yet less complicated modes, and for reasons that remain unclear, he affixes his attention to Edwina, the resident teacher who feels stifled by her duties (an early scene shows her class conjugating the day-one French to be verb être). Does he feel imprisoned and want to escape? Is he just trying to manipulate the easiest of the bunch? If so, to what end?

Earlier this year, Coppola received the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival for The Beguiled. Surely there’s good reason to feel taken by the production. Shot in Louisiana in the Madewood Plantation House on a property of hunched Willow trees and overgrown gardens, the film adopts the surrounding atmosphere of humidity and history. Cinematographer Philippe Le Sourd, best on Ridley Scott’s forgotten romance A Good Year (2006), shoots in natural light, which is particularly effective in the evening scenes lit by candles, where ambiguous browns fill the dark spaces between people. Production designer Anne Ross and costume designer Stacey Battat saturate the material in period detail, while the sound design seems to relish the way voices and footsteps on a wooden floor echo in these old rooms. Clocking-in at a dragging 94-minutes, the film looks gorgeous on the surface but contains a troubling lack of historical context.

Take the film’s curiously over-sympathetic attitude toward Southern Confederate white women who, invariably, were slave-owners. It’s a perspective that seems inappropriate given the state of America today. Coppola sidesteps a discussion of slavery, omitting any person of color from the proceedings. But Cullinan’s book and the 1971 film featured the slave Hallie, played by Mae Mercer in a role that was both sexually charged and, quite appropriately, prevented Martha and her students from seeming too sympathetic. McBurney even found some common ground with her, saying, “You and I ought to be friends. We’re both kind of prisoners here.” In the film’s press notes, Coppola stated, “I didn’t want to have a slave character in The Beguiled because that subject is a very important one, and I didn’t want to brush it over lightly.” Her solution, rather than writing a script that adequately addresses the issue, was to omit any black characters from a Southern tale about the Civil War. To be sure, Coppola puts any notion of slavery out of mind, which forces one to consider why she wouldn’t just choose a different historical era and setting for her picture. Instead, as Amy tells McBurney, “All the slaves ran away,” which allows Coppola to investigate the central female-male relationships, but not in a way that makes much sense from a historical perspective.

Moreover, every trashy and sensational component of the original has been reduced to whispers and understatement. Thus the motivations for Coppola’s characters remain uncertain and uninvolving. Consider the big moment of the film, when McBurney goes to Alicia’s room rather than Edwina or Martha’s. When Edwina catches him planting kisses on Alicia, she pushes McBurney and inadvertently sends him rolling down the stairs. In the original, Martha amputates McBurney’s broken leg from the fall in a clear act of symbolic castration, retribution, and imprisonment. Here, Coppola hasn’t given Martha the necessary backstory to justify her character’s feelings of solitude or vengeful jealousy. Therefore, during a loud scene when McBurney lashes out and claims his fall down the stairs and surgery was revenge for not going to bed with Edwina or Martha, the moment seems emotionally unjustified. Aside from this scene, Coppola keeps everything subdued to such a degree that when the situation needs to explode, it feels as though the bomb goes off without the wick having been lit.

It would be too easy to blame the actors for the lack of onscreen passion—though, Kidman’s Martha feels locked up and far too composed, whereas the original’s Martha, Geraldine Page, maintained her veneer but crackled on the inside. The entire cast is subject to Coppola’s characteristically understated direction. And her script, which she has not so much readapted from the book or earlier film than denied certain scenes their place in her remake, leaves her film lifeless and improperly motivated. It feels as though the characters function in an obligatory way, dictated by the requirements of the story; none of them have any inner being or dramatic arc, aside from perhaps an underdeveloped Edwina. The problem with The Beguiled resides in Coppola’s treatment, which attempts to bring prestige and class to a sultry, sordid tale that should feel inherently campy. Worst of all, her remake also ignores the greater implications of the historical setting. She evades any remarks whatsoever on the era’s treatment of race and has nothing significant to say about women of the period, all by oversimplifying a complicated situation in naïve ways.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review