Okja

By Brian Eggert |

Bong Joon-ho’s Okja follows a teenage girl who tries to protect her pet—the title’s genetically engineered, problem-solving-smart, six-ton superpig—from an evil corporation bent on turning it into processed foodstuff. The South Korean helmer rearranges several genres and defies expectations with his tale, undermining any tonal consistency for an experience that challenges the viewer to keep pace both narratively and emotionally. Yes, there’s a lot to consider. Okja contains themes taken from a-boy-and-his-dog scenarios, where an imperiled animal requires rescue while its owner must face some harsh truths about mortality. But Bong incorporates critiques throughout: industrial factory farming; the inhumane capitalism that mass-produces meat product for hungry consumers; genetically modified organisms (GMOs); meat eating in general; televised animal show celebrities who sell their brand to animal-unfriendly causes; and irresponsible animal rights activism. It doesn’t end there—beyond a critical examination of the meat industrial complex, he also delivers a heist film, a fantasy reminiscent of last year’s Pete’s Dragon, and a touching drama. And on top of all this remains a tender, heart-wrenching story about a girl who loves her animal friend.

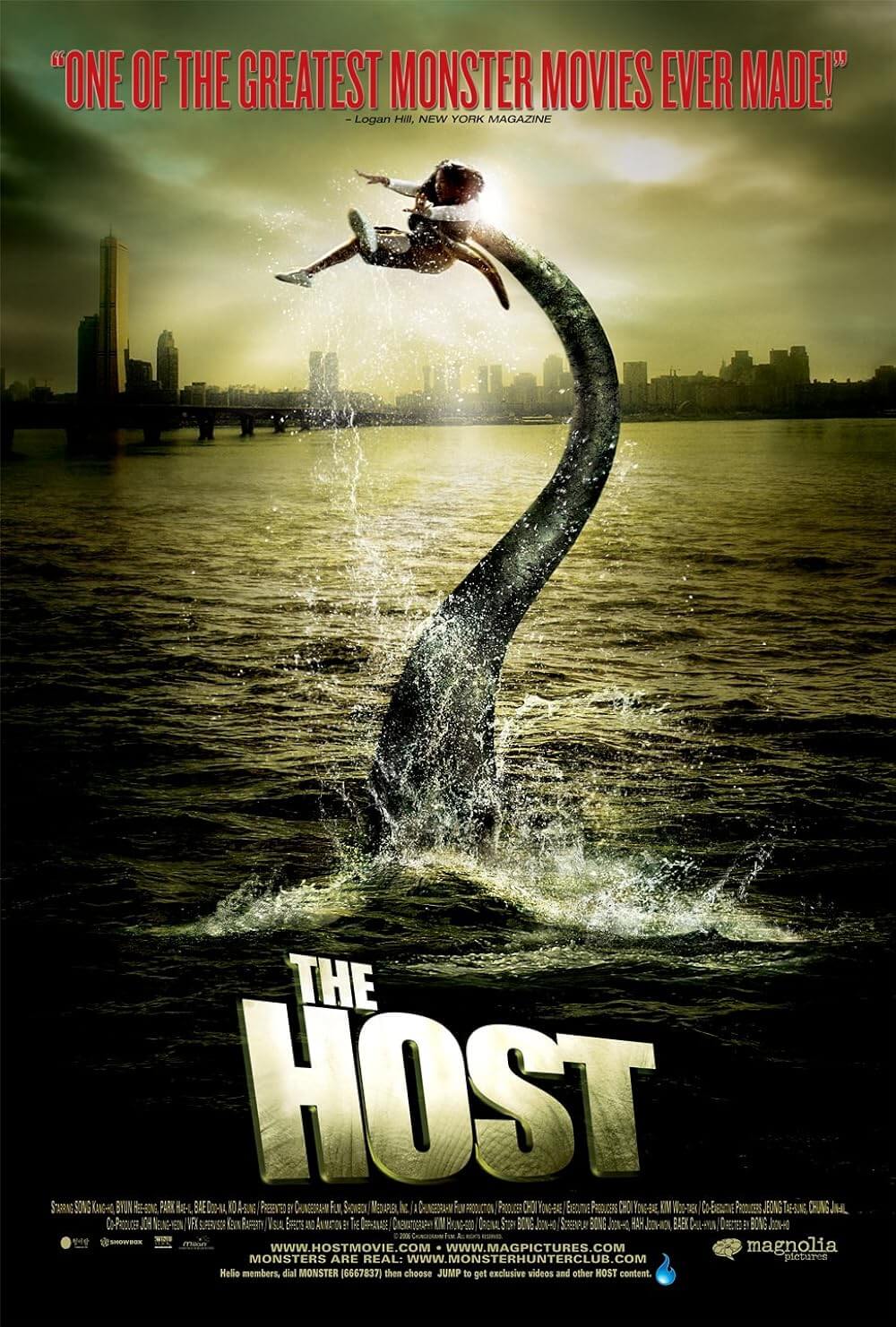

Before watching Okja, viewers should remind themselves of its director’s other features, such as The Host (2006) or Snowpiercer (2014), both films that contain a commentary on the consequences that befall humanity and Nature when corporate interests rule. Bong subverts all genre conventionalities in his work, leaping from slapstick humor in one scene to an unflinching depiction of animal cruelty in the next. A single sequence might contain such a myriad of emotion that the viewer trained in formulaic Hollywood material won’t know what to expect. Bong’s films may showcase the worst of human greed and bureaucracy, but they also value the bonds between families and friends, celebrating innocence and lamenting its corruption. His films are joyously exhausting in the same way Terry Gilliam’s are—the range of surreal stimuli is bound to leave the viewer drained, albeit contemplative and affected. We laugh riotously in one scene, feel thrilled in the next, and we’re very often brought to tears at some point.

But before any of that, we meet Lucy Mirando (Tilda Swinton, downright amazing), the chief executive of the Mirando Corporation who’s trying to reclaim her company from the stigma brought down by her psychopathic father and methodical twin sister. In 2007, Lucy announces an oxymoronic concept: a green plan to genetically engineer a new breed of swine that grows bigger, eats less, produces a small environmental footprint, and will feed countless humans. 26 specimens are delivered to free-range farmers throughout the world, and in 10 years, whoever has the largest, healthiest specimen will win Mirando’s grand superpig pageant. To promote the contest worldwide, she hires TV star and animal guru Johnny Wilcox (Jake Gyllenhaal, delivering his most incredibly outlandish performance since Bubble Boy) and his entourage (Yoon Jae-moon and Shirley Henderson) to promote the event.

But before any of that, we meet Lucy Mirando (Tilda Swinton, downright amazing), the chief executive of the Mirando Corporation who’s trying to reclaim her company from the stigma brought down by her psychopathic father and methodical twin sister. In 2007, Lucy announces an oxymoronic concept: a green plan to genetically engineer a new breed of swine that grows bigger, eats less, produces a small environmental footprint, and will feed countless humans. 26 specimens are delivered to free-range farmers throughout the world, and in 10 years, whoever has the largest, healthiest specimen will win Mirando’s grand superpig pageant. To promote the contest worldwide, she hires TV star and animal guru Johnny Wilcox (Jake Gyllenhaal, delivering his most incredibly outlandish performance since Bubble Boy) and his entourage (Yoon Jae-moon and Shirley Henderson) to promote the event.

Ten years later in South Korea, an orphan named Mija, played in harrowing expressions by An Seo-hyun, and her grandfather (Byun Hee-bong), have raised their superpig named Okja in the mountains in quiet serenity. Mija and Okja have a relationship of not-so-unspoken bonds—signaled by the whispers she delivers under Okja’s floppy ears, and the look of acknowledgment in Okja’s small, expressive eyes. A CGI creation (with occasional practical FX) that looks like a manatee crossed with hippopotamus, Okja has the personality of an inward canine, thoughtful and even soulful. Before long, Wilcox comes to claim Okja, the top superpig, for the upcoming pageant. But that has been hidden from Mija. When she discovers Okja gone, taken by Mirando, she sets out on a rescue mission. She soon intersects with the Animal Liberation Front (headed by Paul Dano, Lily Collins, and Steven Yeun), a group determined to capture evidence of and expose Mirando’s animal wrongdoing and, eventually, Okja, preferably in the most public way possible.

Okja has much in common with the films of the great Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, whose Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and Princess Mononoke (1997) beautifully, fancifully weigh the inevitable destruction of Nature by humanity. Of the film’s themes, it must be said that the forward thrust of the narrative never allows the message to overtake the dramatic stakes or our emotional investment in Mija saving Okja from a bloody fate. Most meat-eaters maintain a state of cognitive dissonance toward slaughterhouses, focusing instead on the taste and sensuous pleasures derived from meat eating. People tell themselves that animals function on instincts alone, that their lives exist free of personality or even emotional bonds. And with every morsel chewed and swallowed, the suffering and inhumane treatment of the animal, which was probably raised and killed on an assembly line, is ignored for our momentary pleasure. Of course, I should qualify the hypocrisy of such statements and sentiments on my part, as they come from a regular meat eater (with a guilt complex firmly in place). But like Miyazaki, Bong seeks to understand and underscore the crisis between people and Nature—because people are a part of Nature.

On a separate note, Okja debuts on Netflix the same day and date as its extremely limited theatrical run, meaning the film will be seen more in home theaters or on small devices than an immersive cinema. Having premiered Okja at this year’s Cannes Film Festival to cheers for the film (but boos at the very sight of the Netflix logo) the company’s choice not to distribute their original films in theaters has been met with harsh, albeit justified criticism. Their films appear on their platform without much marketing or promotional build-up beforehand, and most of them disappear into the ether that is Netflix’s inventory of streaming content. In the past, outstanding films like Beasts of No Nation (2015) never had the opportunity to receive proper word-of-mouth praise because most Netflix viewers only half-watch anyway, and then quickly move on to the next binge-worthy offering without a second thought about what they’ve just seen. But films like Okja should be seen on a big screen, where all distractions (phones, tablets, and any number of household interruptions) fade away and the experience draws your attention in its entirety. Moreover, film festivals and awards aren’t likely to acknowledge Netflix originals due to their virtually nonexistent theatrical presentation (Okja opened in two theaters in New York, two in Los Angeles, with no plans to expand).

On a separate note, Okja debuts on Netflix the same day and date as its extremely limited theatrical run, meaning the film will be seen more in home theaters or on small devices than an immersive cinema. Having premiered Okja at this year’s Cannes Film Festival to cheers for the film (but boos at the very sight of the Netflix logo) the company’s choice not to distribute their original films in theaters has been met with harsh, albeit justified criticism. Their films appear on their platform without much marketing or promotional build-up beforehand, and most of them disappear into the ether that is Netflix’s inventory of streaming content. In the past, outstanding films like Beasts of No Nation (2015) never had the opportunity to receive proper word-of-mouth praise because most Netflix viewers only half-watch anyway, and then quickly move on to the next binge-worthy offering without a second thought about what they’ve just seen. But films like Okja should be seen on a big screen, where all distractions (phones, tablets, and any number of household interruptions) fade away and the experience draws your attention in its entirety. Moreover, film festivals and awards aren’t likely to acknowledge Netflix originals due to their virtually nonexistent theatrical presentation (Okja opened in two theaters in New York, two in Los Angeles, with no plans to expand).

Online companies like Netflix and Amazon have been shopping at Sundance and other film festivals in recent years, picking up prestige indies for distribution on their respective platforms. However, Netflix should take a cue from Amazon, which purchased and distributed some of 2016’s best films into U.S. theaters months before making them available on AmazonPrime (Manchester by the Sea, Love & Friendship, Paterson, and The Handmaiden, to name just a few). Amazon’s films were appropriately marketed, reviewed, and showered with awards throughout last year, while the jury at Cannes has resolved not to allow future Netflix titles into competition unless they receive a proper theatrical release. But Netflix hopes to forgo theatrical viewing—you know, the thing that differentiates cinema from television—by buying up smaller films for millions and then dumping them into their streaming service with no ceremony whatsoever. The few titles to receive proper acknowledgment, like Okja, do so because critics and audiences take an active role in championing them, since Netflix apparently isn’t interested in participating in the film industry or its traditions. Of course, I’m not suggesting that Netflix sets aside all innovations and digital strategies; but there is a market, and an impassioned audience, for seeing films like Okja on the big screen—in a dark auditorium, surrounded by fellow cineastes, the way films were meant to be watched. Netflix’s approach leaves this critic particularly sore given that Okja is vastly superior to most films in theaters right now.

At any rate, Bong’s filmmaking taps into several, seemingly conflicting styles at once, daring the viewer to match its varied pitch. In the more wondrous, family-centric scenes, he echoes a notably Spielbergian tone. Shot by expert cinematographer Darius Khondji (The Lost City of Z, another superb theatrical release from Amazon), the film has Spielberg’s at once epic yet personalized look. But there’s also a decidedly dark edge, as though the aforementioned Gilliam has taken over certain scenes and impregnated them with the same blithe cynicism and frenzied artistry that inhabits his masterpiece, Brazil (1985). Bong’s divergent inflections also inform the performances, from Swinton’s desperate enthusiasm to the sedate goodness of Dano. Like the film itself, most viewers won’t know what to make of Gyllenhaal, whose performance channels Richard Simmons crossed with Michael Jeter in The Fisher King. An Seo-hyun preserves our emotional investment through little dialogue and her looks of desperation; she’s meant to embody innocence and goodness, and her delivery is charmed.

At any rate, Bong’s filmmaking taps into several, seemingly conflicting styles at once, daring the viewer to match its varied pitch. In the more wondrous, family-centric scenes, he echoes a notably Spielbergian tone. Shot by expert cinematographer Darius Khondji (The Lost City of Z, another superb theatrical release from Amazon), the film has Spielberg’s at once epic yet personalized look. But there’s also a decidedly dark edge, as though the aforementioned Gilliam has taken over certain scenes and impregnated them with the same blithe cynicism and frenzied artistry that inhabits his masterpiece, Brazil (1985). Bong’s divergent inflections also inform the performances, from Swinton’s desperate enthusiasm to the sedate goodness of Dano. Like the film itself, most viewers won’t know what to make of Gyllenhaal, whose performance channels Richard Simmons crossed with Michael Jeter in The Fisher King. An Seo-hyun preserves our emotional investment through little dialogue and her looks of desperation; she’s meant to embody innocence and goodness, and her delivery is charmed.

Unfortunately, one of 2017’s very best films arrives by way of Netflix, the streaming service determined to revolutionize the way consumers watch films by limiting them to a lesser in-home experience. Nevertheless, Okja resists all forms of conventional entertainment, even though (as above) it can and has been compared to several well-known films and filmmakers’ styles. The average viewer may find themselves incapable of reconciling what are bound to be perceived as sudden, unruly, jarring shifts in temperament. But Bong’s masterful control of the film’s multiple personalities results in a lingering thought—that people should educate themselves about what they’re eating, and then force themselves to consider why some cultures deem animals worth eating and others worth protecting as pets. What does it say about a culture when it denies qualities determined to be humanistic just because they appear in an animal? So many thoughts come to mind after Okja, it’s impossible to unpack them all in a review. Somehow, the very same qualities that make the film seem masterful might also be used to describe it as a mess. However you describe it, Bong’s ambitions remain onscreen in an admirable, deeply resounding effort. If only that screen was about two stories bigger.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review