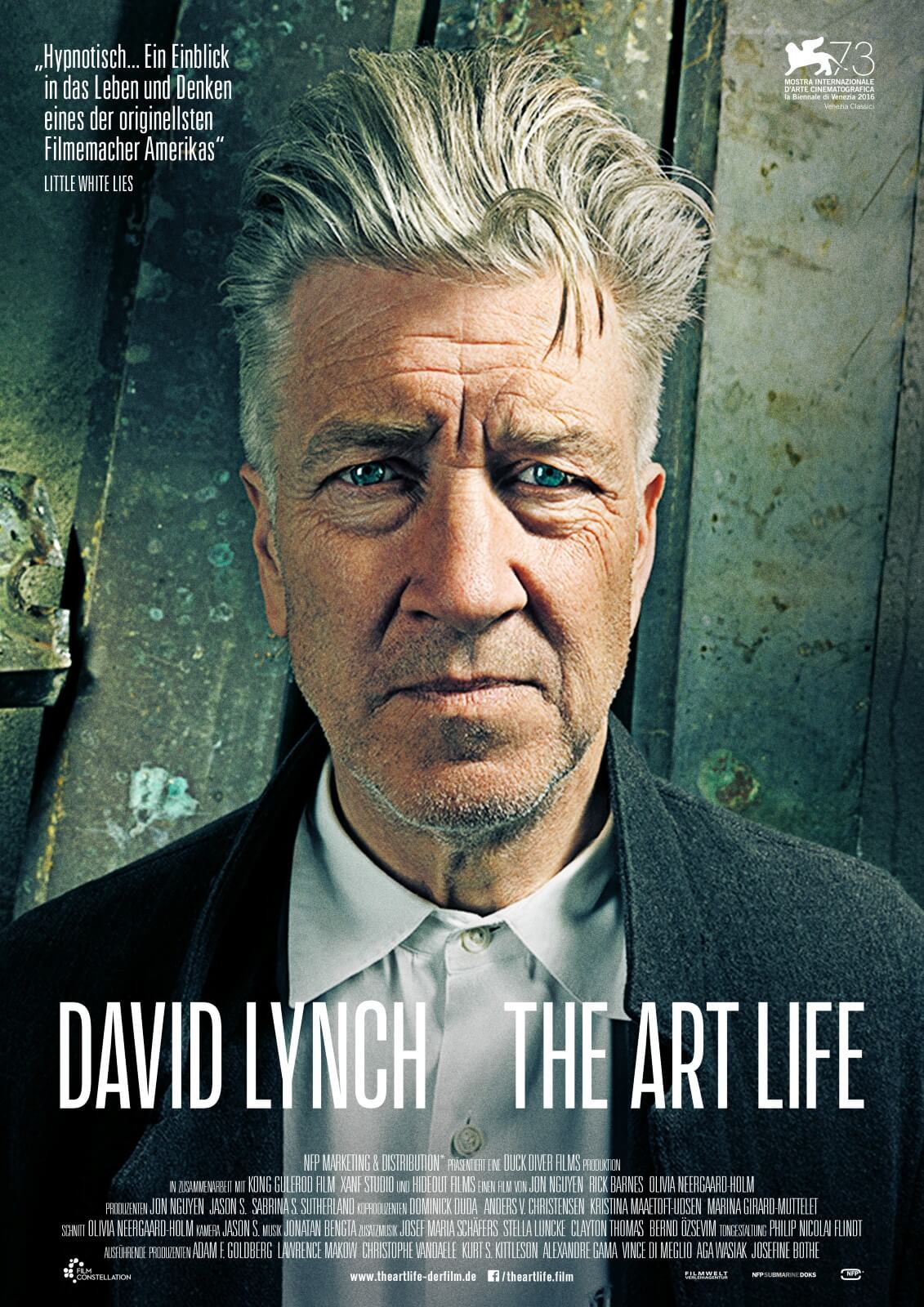

David Lynch: The Art Life

By Brian Eggert |

At the age of 71, David Lynch is experiencing a cultural resurgence unlike anything his celebrity has undergone since the early 1990s. After debuting his beloved television show Twin Peaks in the spring of 1990, he went on to win the Palme d’Or a month later at the Cannes Film Festival for his rapacious and carnal Wild at Heart. The artist-filmmaker was on a career high unlike anything he had known before. But his year of glory was followed by a series of disappointments. The second season of Twin Peaks fizzled out, resulting in its cancellation in 1991. Another show developed by Lynch, On the Air, never connected with audiences. And his much-anticipated film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992) failed to satiate or answer fan questions. Over the last two decades, Lynch’s output has been uneven, consisting of short films, one of the best films ever made with Mulholland Drive (2001), and lesser efforts like Inland Empire (2006). Now, in 2017, he seems to be everywhere again, with a new iteration of Twin Peaks on Showtime for an 18-episode season, career retrospectives of his work at repertory theaters across the country, and a new documentary about his early life as a painter, called David Lynch: The Art Life.

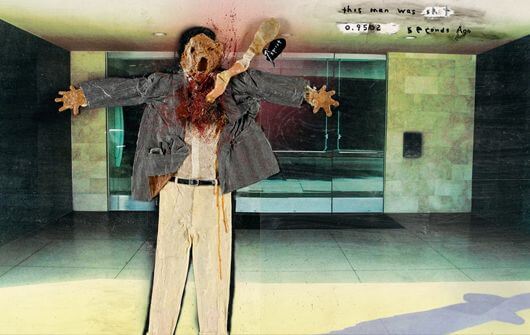

Part of a documentary trilogy of sorts, The Art Life follows Lynch (One) and Lynch 2, both released in 2007. Co-director Jon Nguyen collaborated with Olivia Neergaard-Holm and Rick Barnes over a series of three years, recording twenty audio conversations with Lynch at his house in the Hollywood hills. The footage shows Lynch working in his studio, assembling works of fine art, paintings and sculptures (sometimes a combination of both). The audio interviews (taped in a small studio with a large, metallic microphone) play over footage of his creative process, family photos from his distant past, or rabid montages of his artwork. The interviews have been organized to create a loose biography of his pre-Hollywood life, extending from his early childhood memories to his rough adolescent rebellion, and finally ending around the time he completed work on his breakthrough, the experimental cult masterpiece Eraserhead (1977).

Long segments of the film involve the camera watching Lynch create in his studio; he drills fleshy bits of plastic to wood, glues things together, and spreads globs of paint onto a board with his hands. Some scenes feature Lynch just sitting, usually with a lit cigarette hanging from his mouth, as he waits for inspiration for a work-in-progress. At times, the camera spies its subject’s toddler-age daughter Lula (named after Laura Dern’s character in Wild at Heart) from his most recent marriage to Emily Stofle. Alongside Lula, Lynch looks like a big kid discovering what to do with brushes, paint, and color. Although, he’s been a painter far longer than a filmmaker, having practiced in non-traditional and experimental forms of painting since his high school years. Early in his life, the artist Bushnell Keeler gave Lynch a copy of Robert Henri’s book The Art Spirit. Lynch remarks, “I can’t remember much about it now, but ‘the art spirit’ became ‘the art life.’ And I had this idea that you drink coffee, you smoke cigarettes, and you paint. And that’s it.”

Lynch’s art follows no established school of method or creative norms; he seems to follow his instincts, informed by his dreams and memories. The viewer makes unavoidable associations between painting after disturbing painting and the stories of his personal anxieties and internal preoccupations, which also saturate his films. Meanwhile, Lynch recounts his youth living in an idyllic American suburb with a hard-working father and a mother who supported his artistic drives. But his pleasant memories eventually give way to unsettling episodes. In one story, he recalls as a boy seeing a completely naked and battered woman in his neighborhood, and the description cannot help but echo a notorious scene with Isabella Rossellini in Blue Velvet (1986). In another story, he talks about a morgue night watchman who allowed Lynch to see room of bodies. But the most terrifying of them all remains a mystery. Lynch talks about when his family moved, and their neighbor, Mr. Smith, who came over to say goodbye. Lynch seems to freeze-up during the recollection. “I can’t tell the story,” he says. What could have been so horrifying that David Lynch, who has conjured such uncanny nightmares in his films, could not talk about it?

Lynch’s art follows no established school of method or creative norms; he seems to follow his instincts, informed by his dreams and memories. The viewer makes unavoidable associations between painting after disturbing painting and the stories of his personal anxieties and internal preoccupations, which also saturate his films. Meanwhile, Lynch recounts his youth living in an idyllic American suburb with a hard-working father and a mother who supported his artistic drives. But his pleasant memories eventually give way to unsettling episodes. In one story, he recalls as a boy seeing a completely naked and battered woman in his neighborhood, and the description cannot help but echo a notorious scene with Isabella Rossellini in Blue Velvet (1986). In another story, he talks about a morgue night watchman who allowed Lynch to see room of bodies. But the most terrifying of them all remains a mystery. Lynch talks about when his family moved, and their neighbor, Mr. Smith, who came over to say goodbye. Lynch seems to freeze-up during the recollection. “I can’t tell the story,” he says. What could have been so horrifying that David Lynch, who has conjured such uncanny nightmares in his films, could not talk about it?

Lynch reflects on his teenage years with regret about his rebellious streak, his impatience with social life, and his disdain for standard coursework; mostly he regrets that his parents felt disappointed in him. He eventually discovered painting and focused his energies on creation and living “the art life,” and later married his first wife Peggy Lentz in the late 1960s. Before long, he and Peggy moved to Los Angeles (where he’s lived ever since) and had a daughter (director Jennifer Lynch). In a rather funny-yet-sad story, Lynch recalls how he learned about Peggy’s pregnancy just after his father told him, “Dave, you should never have children” in response to seeing some of his artwork. Sometime later while painting, Lynch remembers imagining colors of green and red moving on a largely black canvas. He formed an idea: “A moving painting, but with sound.” And after creating several experimental shorts and underground films, Lynch famously earned a grant from the American Film Institute that allowed him to make Eraserhead.

Unlike last year’s De Palma, another biographical doc of a filmmaker, The Art Life is less a chronological journey showcasing each film in Lynch’s oeuvre, or even a series of biographical factoids about his life. The filmmakers allow Lynch’s interviews to guide what might be called the story of the film, while they also offer non-audio narrational influence on Lynch’s comments through editing. Juxtaposing his stories with images of his art demonstrates how his life experiences have conjured an uncommon artist. In addition to providing a rare glimpse at an artist at work in his studio, The Art Life colors his cinematic work. Perhaps his films have never been just films. After watching this doc, they seem to be pure works of art to him, whereas the film industry attempts to fit his unique vision into a commercial format, sometimes with ungainly results (see Dune from 1984). The film provides Lynch novices and fanatics with a fascinating peek inside of his entirely self-contained, self-created world, and the result is similar to his films in that it’s fascinating, a little scary, visually engrossing, and worth every second.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review