The Definitives

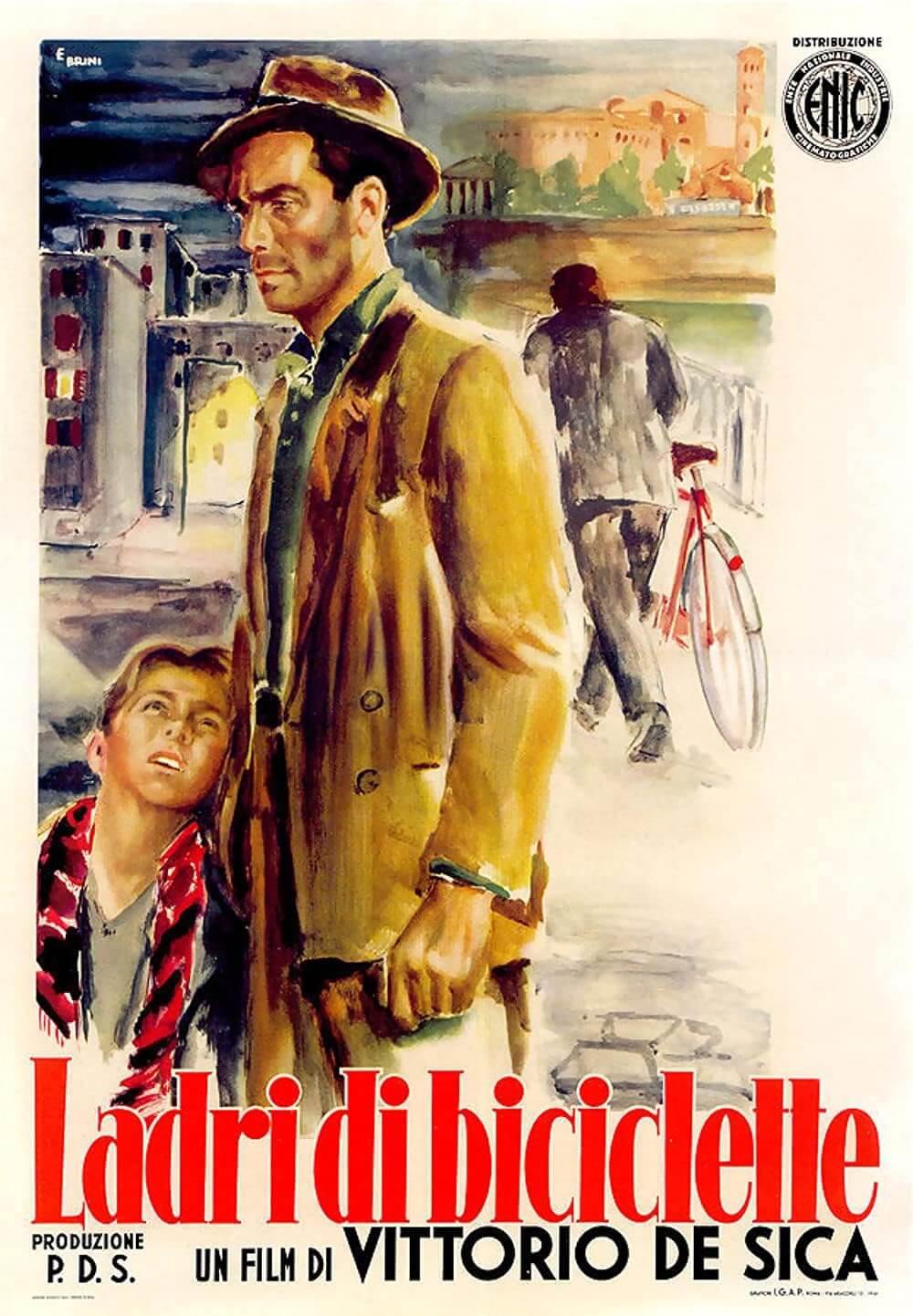

Bicycle Thieves

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Bicycle Thieves takes place at a very specific time under a unique series of social conditions that shape both its narrative and its embrace of the Neorealist message. Though its specificity may preclude it from appealing to larger audiences, Italian director Vittorio De Sica’s film is universally human. The picture tells a simple tale of a man searching for his bicycle, which he needs to relieve his painfully long period of unemployment. Underneath the film’s surface rests an incredibly multifaceted application of aesthetic and formal innovation, commentary on the oppression of working classes, specific sociopolitical conditions at play in Italy at the time, and an investigation into the geographical psychology that affects various social entities within the urban environment of postwar Italy. And yet, Bicycle Thieves contradicts its inward complexity with an outward simplicity of raw emotional power. Of course, it can be screened in both ways: a layered examination of a complex series of intertextual, historical, social, and political concerns; or a heartrending narrative about people trying to survive in a world that devalues their existence as human beings. But at its most essential, the film cries out with humanity, establishing its place of renown in the highest ranks of international cinema.

To begin, consider the intricate sociopolitical climate of Italy just before the film’s release in 1948: Italy would hold its first elections since the twenty-year Fascist rule ended in 1943. The country had organized after the civil war ended in 1945 (in which the Italian Resistance and Co-Belligerent Army fought against and defeated the Fascist Social Republic). After the Liberation, and under the Allied occupation, the Italian Communist Party aligned with a coalition of Christian Democrats, socialists, and liberals to guide the country into a democratic future by penning a new constitution and eradicating the monarchy. The newly established Republican Constitution ended suffrage, meaning the people—the partisan Resistance forces that objected to Nazism and Fascism alike—could finally retake control of their country. The election found the Christian Democrats standing in opposition of, and eventually winning against (thanks to the support of the Vatican and CIA), the communist’s Popular Democratic Front. At the same time, Italy’s economic situation remained in shambles until the United States injected around $12 billion into the European infrastructure with the Marshall Plan, beginning in April of 1948. Until then, Italy maintained millions of unemployed citizens.

Before the Christian Democrats took power, Italy had collectively sought a cultural and creative renewal to distance themselves from the war and dictatorship, not to mention the dominant, rather nightmarish fantasy and style of Fascism. Filmmakers went to the streets to find authentic stories about everyday people, often shooting with untrained actors and natural lighting throughout Rome. They dismissed the collective and nationalistic concerns of Fascist cinema, concentrating instead on the individual, often in juxtaposition with the social conscious of the time. These films would be lumped together under a particular “ism” often inaccurately, though Bicycle Thieves marks a rare, true entry in the Neorealism form. Subsequent pictures have been debated about how well or not they fit the schema, making Neorealism a movement in which only a handful of films qualify, and whose start and end dates have been contested by film historians. Films like Roberto Rossellini’s trilogy Rome, Open City (1946), Paisàn (1946), and Germany Year Zero (1948) remain uncontested, while various contributions from filmmakers like Luchino Visconti, Giuseppe De Santis, and De Sica have been included in the realm of Neorealism. But more than any kind of formal mode, the movement was more about a rejection of Fascism, and therefore temporarily given the historical context of the changing Italy.

Before the Christian Democrats took power, Italy had collectively sought a cultural and creative renewal to distance themselves from the war and dictatorship, not to mention the dominant, rather nightmarish fantasy and style of Fascism. Filmmakers went to the streets to find authentic stories about everyday people, often shooting with untrained actors and natural lighting throughout Rome. They dismissed the collective and nationalistic concerns of Fascist cinema, concentrating instead on the individual, often in juxtaposition with the social conscious of the time. These films would be lumped together under a particular “ism” often inaccurately, though Bicycle Thieves marks a rare, true entry in the Neorealism form. Subsequent pictures have been debated about how well or not they fit the schema, making Neorealism a movement in which only a handful of films qualify, and whose start and end dates have been contested by film historians. Films like Roberto Rossellini’s trilogy Rome, Open City (1946), Paisàn (1946), and Germany Year Zero (1948) remain uncontested, while various contributions from filmmakers like Luchino Visconti, Giuseppe De Santis, and De Sica have been included in the realm of Neorealism. But more than any kind of formal mode, the movement was more about a rejection of Fascism, and therefore temporarily given the historical context of the changing Italy.

After the Christian Democrats took power following the April 1948 election, the country remained politically and socially divided by a series of charged protests, an assassination attempt (the shooting of Italian Communist Party leader Palmiro Togliatti in July 1948), and violent demonstrations. Such unrest was followed by the ruling party seeking to abolish any depiction of Italians living poor and socially unjust lives from their national film industry. Indeed, in the years after the election, Neorealism would not last long under the new Italian ideology, with many citing its end around 1952, making Bicycle Thieves a rare example of a movement that existed within a brief historical bubble. Even so, it does not portray nor directly reference the times of its making within the film; rather, it shows class divisions, an ineffective employment system, basement Communist meetings, and unforgiving social circumstances of the time. For this reason, it is essential to view Bicycle Thieves less as an emblem of an “ism” but rather an essential piece of international cinema, whose individual narrative and grounded formal tenor contained enough raw emotional power to make its particularity universal.

As for its creators, Bicycle Thieves represents the peak of a longtime collaboration between De Sica and writer Cesare Zavattini, who together maintained a writer-director partnership for over twenty films. Raised in Naples around the stage, De Sica started his career as an actor, leading to his formation of a theater company and eventually his transition into cinema, where he played the leading man in several romances and comedies before directing. Prior to writing screenplays, Zavattini wrote experimental novels and dabbled in fine artistry until he found cinema in the 1930s. Over the next twenty years, he would write dozens of screenplays and treatments, though his first collaboration with De Sica was in 1944, with The Children Are Watching Us, a heartbreaking story of a young child who witnesses his parents’ disruptive marriage. Their next film, Shoeshine (1946), followed two boys on the streets of Rome whose friendship dissolves as they are subjected to harsh bureaucracies (the film earned a special Oscar in 1947). Bicycle Thieves would mark their third collaboration. The title, along with a few story elements, were lifted from a mischievous text of the same name written by Luigi Bartolini. The book’s subtitle, A Comic Novel of the Theft and Recovery of a Bicycle, Three Times Over, suggested the author’s satiric observations about his contemporary Rome, though Zavattini saw the setting as grim and tragic.

Zavattini first read Bartolini’s novel in 1947 and felt adapting the book represented an opportunity to portray and critique Italian society, yet it would do so through the lens of commonplace individuals. Just as they had done in their previous two efforts, De Sica and Zavattini told a story through which the presence of children puts the desperate behavior of adults into question. The adult is Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani), a citizen of Rome and a long-unemployed father of two, who finally gets a position as a bill poster. Unfortunately, he just pawned his bicycle, which was a requirement to fill the job. His wife Maria (Lianella Carell) resolves to sell bed sheets from her dowry to reacquire the bike and relieve the family’s desperate situation. With his bike, new uniform, and the promise of financial security for his family, Antonio heads to work and pastes up “Rita Hayworth” posters around Rome while his young son Bruno (Enzo Staiola) works at a filling station. But Antonio’s newfound pride and security lasts only a few hours into his first workday. When a thief (Vittorio Antonucci) takes his bike and rides off, Antonio and Bruno must search Rome and recover the key to the family’s livelihood.

Zavattini first read Bartolini’s novel in 1947 and felt adapting the book represented an opportunity to portray and critique Italian society, yet it would do so through the lens of commonplace individuals. Just as they had done in their previous two efforts, De Sica and Zavattini told a story through which the presence of children puts the desperate behavior of adults into question. The adult is Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani), a citizen of Rome and a long-unemployed father of two, who finally gets a position as a bill poster. Unfortunately, he just pawned his bicycle, which was a requirement to fill the job. His wife Maria (Lianella Carell) resolves to sell bed sheets from her dowry to reacquire the bike and relieve the family’s desperate situation. With his bike, new uniform, and the promise of financial security for his family, Antonio heads to work and pastes up “Rita Hayworth” posters around Rome while his young son Bruno (Enzo Staiola) works at a filling station. But Antonio’s newfound pride and security lasts only a few hours into his first workday. When a thief (Vittorio Antonucci) takes his bike and rides off, Antonio and Bruno must search Rome and recover the key to the family’s livelihood.

Antonio gets his job on Friday; on Saturday, he works his first shift, and his bike is stolen; and on Sunday, he and Bruno search for his bicycle. Over the weekend, Antonio’s loss and pursuit of the thief reveal the layered corruption of his society. He searches in a market where stolen goods are often sold, and the casual appearance of a pedophile pestering Bruno seems so commonplace that it’s hardly noticed by Antonio or anyone else. Later, Antonio follows an old hobo (Giulio Chiari) who knows the thief; they enter a church whose members are more concerned with keeping order than the cause of Antonio’s disruptive presence. The hobo eventually tells Antonio where the thief lives, but the corrupt neighbors unite to defend him, badgering Antonio until a cop arrives to inspect the trouble. Antonio knows it’s hopeless when the officer explains any accusation will not hold up in court, given the thief’s number of berating friends who will undoubtedly perjure themselves to support their neighbor. Left hopeless, Antonio heads toward a football stadium on Via Falminia as Bruno struggles to keep up.

The climax finds Antonio dejected and beaten and, what’s more, confronted with the sight of hundreds of bikes lined up in front of the stadium. Bikers fill the streets, each one racing in front of Antonio’s face, taunting him. De Sica creates unbearable tension, cutting between an exhausted Bruno sitting on the curb and Antonio, who paces back and forth, looking at the endless rows of bikes parked in racks, as well as a solitary bike propped against a wall in a nearby alley. When Antonio finally resolves to steal the alleyway bike for himself, the audience has grown complicit in his theft because it means his family will survive. Nevertheless, the owner and several witnesses chase Antonio down, and he squirms in the clutches of countless people who saw him commit the crime. Antonio knows he’s going to prison. But with the arrival of Bruno at his father’s side, the owner takes sympathy on the father and resolves not to file charges. Amid the disappointment and insults of witnesses, Antonio and Bruno walk home without a bike and disappear into a crowd.

Bruno’s shocked and wounded expression at seeing his father become a thief remains one of the great moments in all cinema. Though he appears about eight years old, Bruno carries the mannerisms and attitude of someone triple his age. He goes out each day just like his father, working a full shift at a filling station; he also cares for his infant sister and scolds his father about the shysters at the pawn shop. Maybe he’s just plucky, as children in films tend to be; but maybe his maturity derives, quite tragically, from necessity. After all, Bruno would have been born around 1940, just as Italy was getting into World War II. Staiola was born in late 1939, which corresponds to his character. Bruno’s father would have been away in the Italian army, as hints early in the film indicate. During this time, Bruno would have been required to grow up fast and help his mother, which might explain why he seems to behave beyond his years. Regardless, he is still a boy. After Antonio smacks Bruno when they lose track of the thief (De Sica reportedly planted cigarettes Staiola’s pocket and accused the boy of stealing them to induce tears), Bruno pouts until he’s treated to a recklessly bought meal of mozzarella sandwiches, wine, and dessert. And after Bruno’s loyalty has been earned back, it is betrayed once more in an unbearably profound sight of his father becoming the very thing they were chasing.

Bruno’s shocked and wounded expression at seeing his father become a thief remains one of the great moments in all cinema. Though he appears about eight years old, Bruno carries the mannerisms and attitude of someone triple his age. He goes out each day just like his father, working a full shift at a filling station; he also cares for his infant sister and scolds his father about the shysters at the pawn shop. Maybe he’s just plucky, as children in films tend to be; but maybe his maturity derives, quite tragically, from necessity. After all, Bruno would have been born around 1940, just as Italy was getting into World War II. Staiola was born in late 1939, which corresponds to his character. Bruno’s father would have been away in the Italian army, as hints early in the film indicate. During this time, Bruno would have been required to grow up fast and help his mother, which might explain why he seems to behave beyond his years. Regardless, he is still a boy. After Antonio smacks Bruno when they lose track of the thief (De Sica reportedly planted cigarettes Staiola’s pocket and accused the boy of stealing them to induce tears), Bruno pouts until he’s treated to a recklessly bought meal of mozzarella sandwiches, wine, and dessert. And after Bruno’s loyalty has been earned back, it is betrayed once more in an unbearably profound sight of his father becoming the very thing they were chasing.

To write the picture alongside De Sica and Zavattini, several credited and uncredited writers convened to discuss and debate the ideologies the film should explore. Clashes between these artists resulted in several abandoning the production; and yet, Zavattini remained the creative force behind the screenplay. While the production prepared and Zavattini wrote, the director and writer went to the streets of Rome to shoot test footage, engaging in an ethnographic exploration of their film’s setting. They discovered locations that would later be used in the film, such as the market and a brothel that Antonio enters in search of the hobo, while they also visited La Santona, the clairvoyant who plays herself in the film. At the same time, De Sica tried to secure financing from potential international investors, including David O. Selznick, who refused to contribute without a star like Cary Grant or Henry Fonda. But the director did not want a star. He eventually brokered a deal with three wealthy investors from Milan who provided a budget over five times that of his previous film. All the while, during the film’s development and after its release, Bartolini remained vocally opposed to De Sica and Zavattini’s treatment of his comic novel.

Zavattini completed the script in April of 1948, and shooting began a month later. De Sica and Zavattini’s partnership was such that, once the writer’s obsessive control over the script resulted in a finished product, the director had complete control without argument from the writer. De Sica shot in the streets of Rome over the summer months, insisting on realism even as he applied an impressive use of technology and directorial manipulation of his on-location shoot. For instance, De Sica did not shoot in the handheld, cinema vérité shooting style of Rossellini’s Rome, Open City. Cinematographer Carlo Montuori and his assistants captured a grand cinematic style even though their presence on Rome’s streets approached guerrilla filmmaking. This unique balance between authenticity and artistry becomes evident in anecdotes about the shoot, such as how De Sica gained control of traffic lights in Rome’s busy Largo Tritone crossroads to switch the traffic on or off at just the right moment during the climactic sequence. Such tactics meant De Sica could organize massive scenes without hiring hundreds of extras while also maintaining stylistic control from a distance.

Bicycle Thieves was edited in the fall of 1948 and first screened on November 21 at a preview at the local film club, Cinema Barberini in Rome. Journalists and critics had already seen rough cuts and covered the filming of the picture extensively leading up to the debut, but the families and friends of those involved in the production celebrated the unveiling. Released wide on December 22, it became Italy’s eighth most successful release of the season, though the film would not hit an international stride until French critic André Bazin praised the film in a 1949 essay. By the following December, Bicycle Thieves reached London and New York, its reputation well-established among critics who had long heard of a mythic arthouse film that seemed to garner the word “masterpiece” wherever it was screened. Joe Breen’s American Production Code tried, and failed, to cut two scenes from the U.S. distribution, leaving a shot inside a brothel and another of Bruno nearly peeing in the film—moments which, for many, signaled the downfall of the Production Code. By 1952, the BFI had included the film at the top of their Sight and Sound poll of the greatest films ever made; in 2012, the film still retained a place on that list.

Bicycle Thieves was edited in the fall of 1948 and first screened on November 21 at a preview at the local film club, Cinema Barberini in Rome. Journalists and critics had already seen rough cuts and covered the filming of the picture extensively leading up to the debut, but the families and friends of those involved in the production celebrated the unveiling. Released wide on December 22, it became Italy’s eighth most successful release of the season, though the film would not hit an international stride until French critic André Bazin praised the film in a 1949 essay. By the following December, Bicycle Thieves reached London and New York, its reputation well-established among critics who had long heard of a mythic arthouse film that seemed to garner the word “masterpiece” wherever it was screened. Joe Breen’s American Production Code tried, and failed, to cut two scenes from the U.S. distribution, leaving a shot inside a brothel and another of Bruno nearly peeing in the film—moments which, for many, signaled the downfall of the Production Code. By 1952, the BFI had included the film at the top of their Sight and Sound poll of the greatest films ever made; in 2012, the film still retained a place on that list.

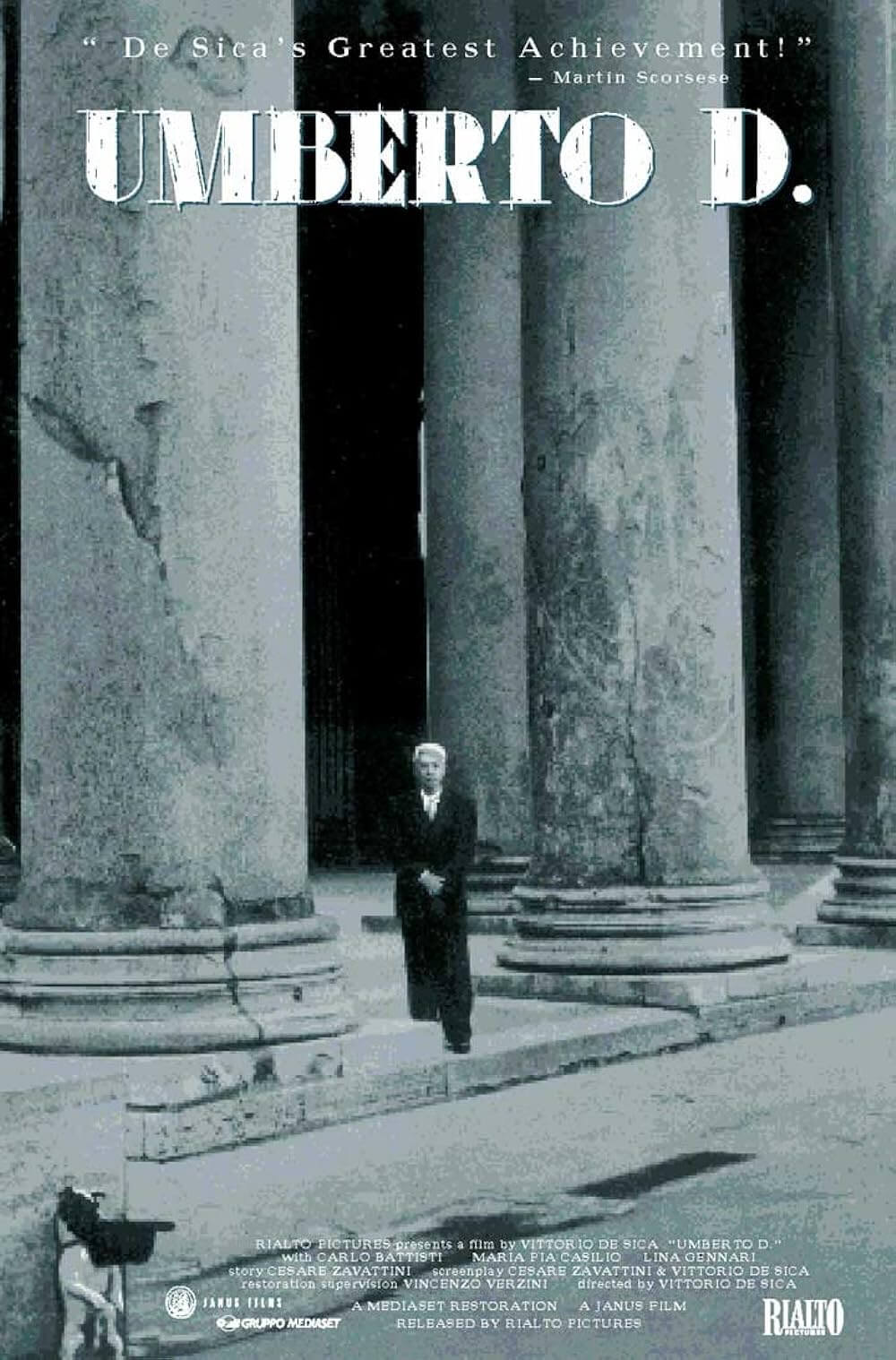

Indeed, Bicycle Thieves is essential cinema that amalgamates the filmmaking traditions of its predecessors while also standing at the forefront of modern European cinema to follow. From the past, De Sica cited silent masters like Charles Chaplin and King Vidor as influencers on his approach. Most apparent is Chaplin’s The Kid (1921), with both films about a father and son, urban and poor, trying to survive, and the father becomes so singularly driven to survive under ruthless social conditions that he nearly forgets about his child. Consider the scene in Bicycle Thieves that Breen almost cut: Bruno stops to pee during Antonio’s pursuit of the old hobo, and his father stops the boy before he can finish, rushing him along with a jolt of urgency. Several moments like this, including Antonio’s pursuit of the hobo around the church, could function as nearly comic sequences if not for the desperate context. De Sica also draws from the silent tradition of angular shadows composed with rich black-and-white photography, and his framing and use of Dutch angles also speak to an expressionistic influence. Of course, Bicycle Thieves shaped the remainder of the Italian Neorealism movement and any other such Neorealism movement in cinema worldwide, although few titles outside of De Sica’s own Umberto D. (1952) achieve its dramatic universality.

As suggested, Bicycle Thieves operates in two distinct modes: the narrative of a profoundly human struggle for survival that remains common to all, and the unromantic depiction of Italian class struggles in the postwar era. In the latter mode, the film illustrates a series of bureaucracies, official behaviors, and social structures that remain indifferent to Antonio and his desperate situation. The film identifies Antonio and his family by their situational relationship, or lack thereof, with various groups present throughout Rome during the postwar period. For instance, Antonio’s family is displaced from his local group of Communists, churchgoers, market folk, and even women at the brothel scene. When Antonio buys Bruno an apologetic meal he cannot afford, they see a well-dressed bourgeois family eating their Sunday feast in the same restaurant. The upper-middle-class life seems to be Antonio’s idyll, aside from their snooty child who looks down his nose at Bruno. Similarly, Antonio’s family does not engage in the era’s evident pastimes (football, cinema, visits to the brothel, nightclub entertainment, etc.). Each institution maintains crushing apathy and disregard for their fellow human beings. Bazin called the film “the only valid Communist film of the past decade,” noting the film’s representation of how “the poor must steal from each other in order to survive.”

P erhaps it goes without saying that Rome and its various neighborhoods serve as pseudo-characters in Bicycle Thieves, from the thief’s neighborhood of fervent defenders to the bourgeoisie depicted in the restaurant. In a way, the film serves as a tour of Rome, showcasing the city’s texture in scenes deep in the urban sprawl, less urban moments along the Tiber, unfinished industrial areas around Porta Portese, civic spaces and forgotten neighborhood hovels, evidence of the Roman antiquity and post-industrial construction, remnants of the Fascist regime, and areas bombed-out by Allied forces. Each neighborhood within Rome presents a unique array of real and fictional characters, and most of them remain indifferent to Antonio’s dilemma, justifying his frantic act of survival in the final scene. To be sure, the entire film seems to place Antonio and Bruno in opposition to these crowds and communities, creating a humanistic empathy for their struggle and emphasizing the film’s overall discussion of the individual’s displacement in his society.

erhaps it goes without saying that Rome and its various neighborhoods serve as pseudo-characters in Bicycle Thieves, from the thief’s neighborhood of fervent defenders to the bourgeoisie depicted in the restaurant. In a way, the film serves as a tour of Rome, showcasing the city’s texture in scenes deep in the urban sprawl, less urban moments along the Tiber, unfinished industrial areas around Porta Portese, civic spaces and forgotten neighborhood hovels, evidence of the Roman antiquity and post-industrial construction, remnants of the Fascist regime, and areas bombed-out by Allied forces. Each neighborhood within Rome presents a unique array of real and fictional characters, and most of them remain indifferent to Antonio’s dilemma, justifying his frantic act of survival in the final scene. To be sure, the entire film seems to place Antonio and Bruno in opposition to these crowds and communities, creating a humanistic empathy for their struggle and emphasizing the film’s overall discussion of the individual’s displacement in his society.

Instead of De Sica and Zavattini making grandiose sociopolitical statements within the film, their commentaries inhabit its general milieu, allowing the film’s traditional narrative mode predominance. Despite the complicated stage, the conflict of Bicycle Thieves is a simple quest to recover an object, not unlike the Greek hero Jason’s search for the Golden Fleece, and thus the film could be viewed as more about the journey than the destination. How ironic that the destination, and the central MacGuffin of the film, remains a common and unimpressive bicycle. Even the film seems to remark on the bike’s outward inconsequentiality when Antonio files a police report: A journalist asks whether the case is worth covering, and with Antonio in earshot, a policeman replies, “It’s nothing. Just a bicycle.” Even so, the bike’s importance to Antonio cannot be overstated. It stands as an object with the power to grant Antonio an occupation, livelihood, and survival for his family. Regardless, given the world’s industrialization through cars, scooters, and public transportation, the bicycle seems to be an object of leisure or sport for most. But De Sica structures Antonio’s symbolic ability to live from the bicycle, involving the viewer in a world where the bicycle seems to permeate (bicycles are everywhere in this film).

When Antonio fails to retrieve his or any other bicycle, the film ends with an overwhelming sense of defeat, as though his journey was for nothing. Antonio is back where he started: without a job or a bicycle. As Bazin observed, the story of Bicycle Thieves “might just as well not have happened.” Though Bazin’s remark sounds dismissive, his observation is meant with high praise for a film that follows its protagonist on a journey to, ultimately, nowhere. However severe and unforgiving the representation may be, De Sica tells a universally human story that crossed borders and united cinemagoers on an international scale. He expertly applies dynamics of situational emotion that connect to a life and death struggle, albeit through the most seemingly arbitrary of objects, which, of course, heightens the human drama. Bicycle Thieves is about the greater human experience of suffering and fortitude and how there’s not necessarily a romantic finality in life. Rather, life goes on, people endure hardships, and the film’s story refuses to dramatize or shape the trials and emotions of reality into an orderly escapist fantasy.

Bibliography:

Bazin, André, and Bert Cardullo. André Bazin and Italian Neorealism. The Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011.

Bondanella, Peter. A History of Italian Cinema. The Continuum International Publishing Group, 2009.

Gordon, Robert S. C. Bicycle Thieves. British Film Institute Classics, BFI Publishing, 2008.

Ruberto, Laura E., and Kristi M. Wilson. Italian Neorealism and Global Cinema. Wayne State Univerity Press, 2007.

Snyder, Stephen and Howard Curle. Vittorio De Sica: Contemporary Perspectives. University of Toronto Press, 2000.

Wagstaff, Christopher. Italian Neorealist Cinema: An Aesthetic Approach. University of Toronto Press, 2007.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review