Medicine for Melancholy

By Brian Eggert |

Meandering around San Francisco in a fog of grainy, handheld digital camerawork, the stars of Medicine for Melancholy inhabit a formal world unique to cinema of the early 2000s. Prior to the film’s release in 2009, the digital revolution had been around for years. Young independent talents could head out into the world with a relatively small camera and capture footage by the memory card full. The ability to shoot fast and cheap meant filmmakers could tell stories that might not otherwise be told, and then cut it together on a laptop; the resulting film could show at film festivals and might even get picked up by IFC. A prime example is Richard Linklater’s Tape (2001), a real-time drama shot on digital within the confines of a hotel room (and that’s not the last reference to Linklater in this look back at Medicine for Melancholy). Today, films shot on iPhones look better (see Tangerine).

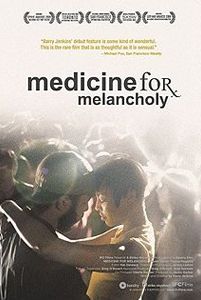

As part of this brief stylistic movement, Medicine for Melancholy remains somewhat commonplace, although today it is perhaps more significant for being the debut of writer-director Barry Jenkins. In the years after its release, Jenkins made short films and developed other, unrealized projects, eventually settling on Moonlight, which won the 2017 Academy Award for Best Picture, while also earning Jenkins an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay and a nomination for Best Director. Looking at the two films in contrast, one cannot help but marvel over the assuredness and artistic composure of his second film. The range of talent, artistic sensibility, control, and narrative demonstrated in his sophomore effort is astounding, whereas its predecessor remains the work of a filmmaker exploring his craft and finding his artistic voice. Similar thematic ideas about identity and a humanizing tone prevail throughout both; but formally, the differences between the two suggests the progression of a curiously more prolific filmmaker.

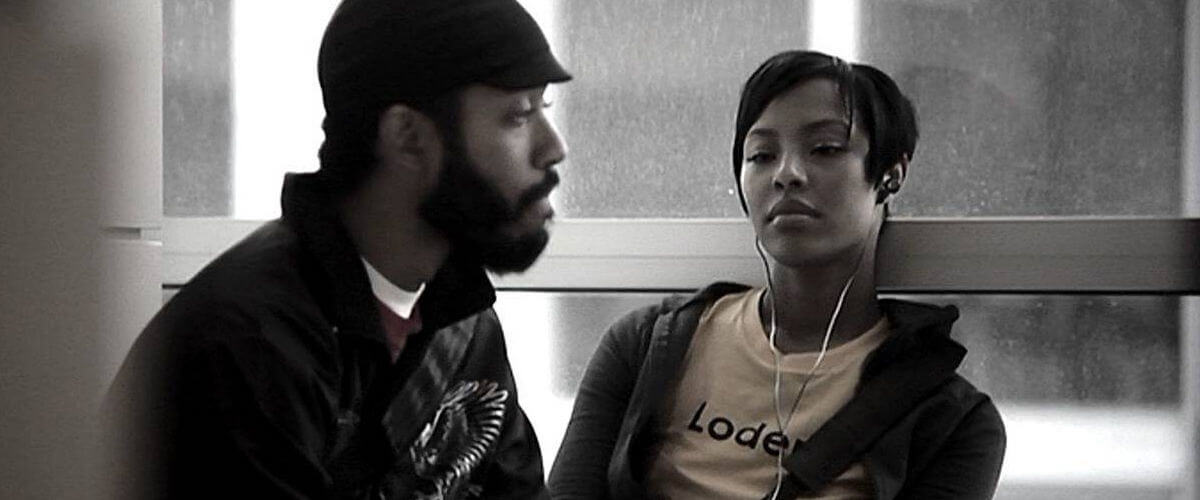

Twentysomething San Franciscans Micah (Wyatt Cenac) and Joanne (Tracey Heggins) wake up next to each other in a Nob Hill apartment, having just slept off their one-night stand. They groggily tiptoe outside, where he asks her to breakfast. Afterward some icy non-conversation, they share a cab, and she leaves her wallet on the taxicab floor, giving him reason to show up at her apartment door. The bearded, good-humored Micah lets his interest be known, while Joanne sees no reason to maintain even social niceties—that is, until he breaks the ice by singing the theme to Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. From here, Medicine for Melancholy turns into a walking-talking romance between two African-American hipsters, recalling something like Linklater’s Before Sunrise (1995) and its sequels, or perhaps even Waking Life (2001).

When the characters engage in conversation or visit a local museum, the film feels alive with a perspective. For instance, Micah asks Joanne to define herself with a single word, which she refuses to do so, believing people are more complicated and intricate than such a basic definition. But Micah labels himself and others through stereotypes; he defines himself as “black” more than a “black man.” Joanne reveals that she has a white boyfriend and asks Micah whether either of those details matter. “Yes and no,” he replies. Nevertheless, there’s a nebulous chemistry between these two, often explored in quiet, dialogue-less moments in which they simply occupy the same space. They are comfortable around one another, and the film ruminates on whether their budding relationship is based on a shared race, heritage, community, or culture. Or maybe none of those factors matter at all.

When the characters engage in conversation or visit a local museum, the film feels alive with a perspective. For instance, Micah asks Joanne to define herself with a single word, which she refuses to do so, believing people are more complicated and intricate than such a basic definition. But Micah labels himself and others through stereotypes; he defines himself as “black” more than a “black man.” Joanne reveals that she has a white boyfriend and asks Micah whether either of those details matter. “Yes and no,” he replies. Nevertheless, there’s a nebulous chemistry between these two, often explored in quiet, dialogue-less moments in which they simply occupy the same space. They are comfortable around one another, and the film ruminates on whether their budding relationship is based on a shared race, heritage, community, or culture. Or maybe none of those factors matter at all.

On the periphery and creeping into the main narrative, Jenkins explores the theme that his characters are black people living in a city that, in 2009, had only a 7% population of African-Americans, the lowest of any major city in America. The director continues his investigation through conversations about gentrification and the high costs of living in San Francisco, ideas which seem forced into the film when Micah and Joanne stop to listen to a group debating such social implications in a roundtable forum. Meanwhile, the film is shot in muted visual style that responds to the characters and their exchanges. As Micah tries to reduce his existence to matters of race, the colors fade from the frame, as if the essence is drained from these characters when one of them reduces their identity to such a narrow view. As those concerns become less important between Micah and Joanne, the color returns. It’s a subtle and effective visual effect.

Medicine for Melancholy captures this essential human discussion, although without much consequence on the characters. Jenkins and his editor Nat Sanders incorporate a lot of footage of Micah and Joanne doing not much of anything. They ride bikes or dance at an indie rock club, and they sit together in silence. Cinematographer James Laxton often juxtaposes the characters against a larger backdrop; however, he also puts his camera in the characters’ faces during a love scene. The two modes of framing suggest that Micah and Joanne both occupy a larger community and remain individuals. The poetic approach to the lensing and treatment of the characters leaves them to feel like ideas rather than people, which remains contrary to the film’s thematic discussion of multifaceted identity. Additional dialogue and engagement between Micah and Joanne may have solidified the characters and bonded them to the audience.

Much like Moonlight, Jenkins explores human beings who struggle with preconceived ideas of identity that are thrust upon them. It is both about African-American identity and not; it’s both about being a San Franciscan and not. Above all, Jenkins demonstrates that his primary concern is personhood, rather than the specific factors of personhood such as race, sexuality, psychological geography, and so forth. Medicine for Melancholy does not always make good use of its brief 88 minutes of runtime, especially given its cinematic conversation that feels much loftier than the film allows. Even so, Cenac (who wrote for The Daily Show from 2008-2015) and Heggins (whose biggest credit since 2009 is the last Twlight film) bring a presence of weighty and human substance to the film, so the audience wants to see them end up together. And while it’s evident that Jenkins is a first-time filmmaker setting out to deliver an Art Film in a specific indie style, his approach and the commentaries throughout are accessible and, of course, bourgeoning with potential.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review