The Definitives

High and Low

Essay by Brian Eggert |

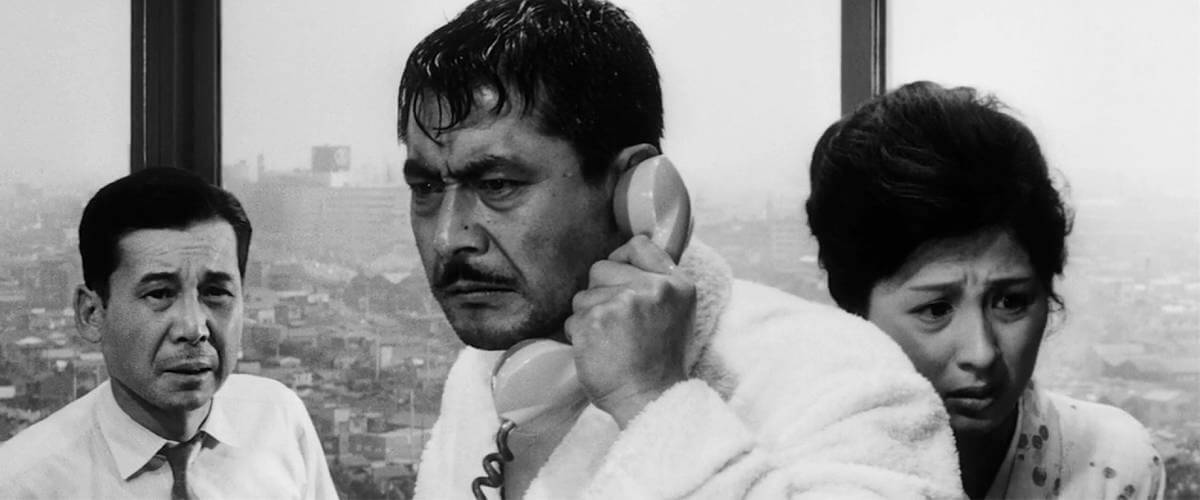

A work of structural and thematic brilliance, Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low does not involve samurai or journeys into Japan’s distant past to create relevant historical parallels, as the director’s pictures often do. Nor does it reformat a classical Shakespearian play or novel by Dostoyevsky into a pointedly Japanese tale. Released in 1963, the film considers a social and class divide present in postwar Japan, engaging its subject through that most Western of subgenres: the kidnapping thriller. The separation of classes and polarity of wealth become the impetus of a mesmerizing and noirish procedural, which—through the course of a tense negotiation, breathless ransom payoff, and subsequent manhunt—equalizes the film’s two divergent central characters: a wealthy shoe company executive who lives atop a hill, and a lowly kidnapper who lives in the slums at the hill’s base. High and Low dissects its characters through a diptych construction, involving its audience in a wealth of human drama to contemplate Kurosawa’s most prevalent, lingering questions about humanity and the factors that prevent us from relating to one another.

Toshiro Mifune, the actor who collaborated with Kurosawa on eighteen films, once wrote of the director, “When you see his films, you find them full of realizations of ideas, of emotions, of a philosophy which surprises with its strength, even shocks with its power. You had not expected to be so moved to find within your own self this depth of understanding.” More simply, Kurosawa sought to understand how people and their sometimes-clashing beliefs coexist: “Why can’t people be happier together?” the director once wrote. This question saturates each of the director’s films, and by attempting to answer a question that seeks to penetrate our basic humanity, he creates connections between filmgoers from various corners of the world. Although he intended his pictures for Japanese audiences alone, his themes resonate beyond the East. Perhaps this stems from his fondness for Western cinema and culture, in particular the films of John Ford. Through his emulation of Western styles, he unconsciously explores the similarities between disparate cultures in narrative, aesthetic, and thematic terms. In many ways, Kurosawa’s films teach audiences better ways of understanding themselves and the worlds they inhabit. Indeed, Kurosawa had such an edifying presence on his sets that many of his collaborators called him their sensei, or teacher, as his films teach about the human condition, the world, and a person’s place in the world.

Kurosawa’s most distinguished works were made just after World War II, when the Japanese people were searching for meaning in their lives following the U.S. nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, and the subsequent Occupation of Japan that lasted until 1952. Due to Western influence, rampant industrialization boomed throughout the country after the Occupation, creating a social divide between those who flourished in economic growth and those who suffered in a widespread condition of poverty, which in turn shaped the personal identity of many Japanese citizens. To be sure, social classes and their hierarchies formed a significant portion of the Japanese cultural identity, including how people perceived others and how they perceive themselves. After all, Japanese culture has a long history of social self-examination derived from political and religious beliefs: Buddhists believe higher classes must look over the frail and unwell; Confucius preached about the necessity of so-called “social superiors and inferiors” having a “reciprocal” relationship; and Japanese imperialist doctrine insisted everyone, regardless of class, was “one family.” Kurosawa believed that, historically, people were too often judged by social factors, making the world cruel and unfair. He set out to make a film with the belief that a person is judged not by their social status or size of their bank account; rather, a person will be judged by the choices they make.

Kurosawa’s most distinguished works were made just after World War II, when the Japanese people were searching for meaning in their lives following the U.S. nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, and the subsequent Occupation of Japan that lasted until 1952. Due to Western influence, rampant industrialization boomed throughout the country after the Occupation, creating a social divide between those who flourished in economic growth and those who suffered in a widespread condition of poverty, which in turn shaped the personal identity of many Japanese citizens. To be sure, social classes and their hierarchies formed a significant portion of the Japanese cultural identity, including how people perceived others and how they perceive themselves. After all, Japanese culture has a long history of social self-examination derived from political and religious beliefs: Buddhists believe higher classes must look over the frail and unwell; Confucius preached about the necessity of so-called “social superiors and inferiors” having a “reciprocal” relationship; and Japanese imperialist doctrine insisted everyone, regardless of class, was “one family.” Kurosawa believed that, historically, people were too often judged by social factors, making the world cruel and unfair. He set out to make a film with the belief that a person is judged not by their social status or size of their bank account; rather, a person will be judged by the choices they make.

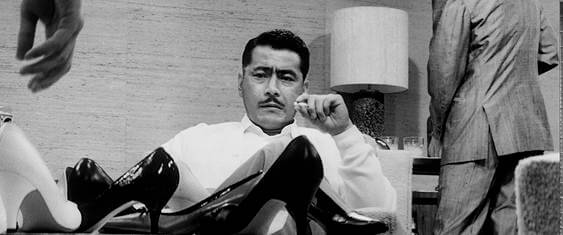

High and Low details a complicated kidnapping scheme, but its themes resonate beyond the plot or even the social statuses of the victim and criminal involved. Structurally, the film is broken into two distinct parts, and the first part could serve as an edgy one-act play about a kidnapping and the subsequent ransom negotiations, its scenes set almost entirely in a luxurious home in the bluffs above Yokohama. The story follows Gondo, played by Mifune, who risks his entire fortune and future career to comply with a kidnapper’s demands. But more than just money, Gondo’s humanity dangles in the balance. When the film opens, Gondo, a factory director for National Shoes, faces pressure from fellow executives who wish to produce a cheaper, lesser-quality product for higher profits. Being a former shoemaker who takes pride in doing good work, Gondo refuses their scheme and, over the course of several phone calls, reveals that he has prearranged a hostile takeover by borrowing and mortgaging his home to secure ¥50 million, much to the surprise of his wife Reiko (Kyoko Kagawa). Betting his entire fortune and family’s livelihood on a gamble, Gondo plans to catch a flight to Osaka to sign the paperwork for his takeover. Just as he’s set to leave, the phone rings. The voice of a kidnapper claims to have nabbed Gondo’s son and demands a ¥30 million ransom.

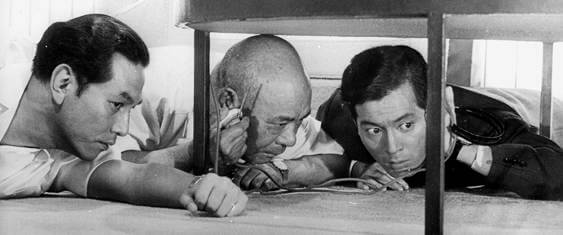

Believing their son was taken, Gondo and Reiko panic and say they’ll pay whatever it takes, even if, upon payment, it ruins Gondo financially. However, they soon learn it was not their son who was kidnapped; it was that of their chauffeur (Yutaka Sada). Several detectives arrive on the scene, led by Det. Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai); they set up recording and tracing equipment and encourage Gondo to cooperate. Despite grabbing the wrong boy, the kidnapper demands payment, much to Gondo’s incredulity. It becomes clear the kidnapper wants more than the ransom; he wants to ruin and humiliate Gondo. Even so, Gondo refuses to pay the ransom, believing at first that his chauffer’s son isn’t worth as much as his own and, moreover, he will lose everything if he pays. Still, Reiko and the detectives encourage him to pay, while the chauffeur, ever loyal, seems to understand Gondo’s hesitation: “You have the right to protect your own life,” he says in a tragic moment of allegiance. Only after much contemplation does Gondo eventually agree to pay the same ransom for his chauffer’s child. Once Gondo hands over the money in an anxious delivery aboard a train, the chauffer’s child is returned. But Gondo remains in financial ruin.

Believing their son was taken, Gondo and Reiko panic and say they’ll pay whatever it takes, even if, upon payment, it ruins Gondo financially. However, they soon learn it was not their son who was kidnapped; it was that of their chauffeur (Yutaka Sada). Several detectives arrive on the scene, led by Det. Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai); they set up recording and tracing equipment and encourage Gondo to cooperate. Despite grabbing the wrong boy, the kidnapper demands payment, much to Gondo’s incredulity. It becomes clear the kidnapper wants more than the ransom; he wants to ruin and humiliate Gondo. Even so, Gondo refuses to pay the ransom, believing at first that his chauffer’s son isn’t worth as much as his own and, moreover, he will lose everything if he pays. Still, Reiko and the detectives encourage him to pay, while the chauffeur, ever loyal, seems to understand Gondo’s hesitation: “You have the right to protect your own life,” he says in a tragic moment of allegiance. Only after much contemplation does Gondo eventually agree to pay the same ransom for his chauffer’s child. Once Gondo hands over the money in an anxious delivery aboard a train, the chauffer’s child is returned. But Gondo remains in financial ruin.

The film’s second half follows a meticulous police investigation to track down the kidnapper, a young medical intern named Takeuchi, played by Tsutomu Yamazaki. Takeuchi lives in the slums of Yokohama, his neighborhood reminiscent of the putrid sprawls Kurosawa depicted in Drunken Angel (1948) and Ikiru (1952)—places soiled by the aftermath of WWII. In the same sweltering neighborhood, detectives investigate phone booths that have a line of sight to Gondo’s white, air-conditioned mansion on the hill. “This house gets to you,” one of the detectives says, “as if it’s looking down at you.” Takeuchi has a view from his apartment of the house that seems to look down on him. How many hours did he spend in his window, looking up and resenting Gondo? Despite getting his demands, Takeuchi, enraged, reads newspaper articles about Gondo and listens to a radio interview that praises him—the kidnapping has turned Gondo into a hero after he sacrificed his fortune to pay the ransom. To hide any evidence of his crime, Takeuchi resolves to burn the cases in which the ransom was delivered. He doesn’t know, however, that the detectives have lined the cases with a dye that will change the color of smoke when burned. Though High and Low was shot in black-and-white, a pink tint appears on the plumes from the smokestack, alerting the authorities to Takeuchi’s location.

Although the first-half’s tight, enclosed structure demonstrated Kurosawa’s visual ingenuity with elegant close-quarters blocking, the second half finds his production shooting in cramped police conference rooms and on location in shady nightclubs and slums. In a quasi-verité style that recalls Kurosawa’s own Stray Dog (1949), the director’s handheld cameras take to crowded city streets teeming with everyday citizens, yakuza gang members, drug dealers, and prostitutes. The second-half could also be considered strange because the basic plot is over; the kidnapped boy was returned home. All that remains is catching the kidnapper, which is less about vengeance or retribution for Gondo than the duty of justice for the police. Nevertheless, the procedural elements of High and Low serve its greater purpose. When the film takes Takeuchi’s perspective, the scenes appear more like film noir, complete with grim shadows and light peering through narrow openings. Takeuchi becomes a doomed character similar to Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity (1944) or Robert Mitchum in Out of the Past (1947)—he made a bad decision, and now the aesthetic structure of the film he inhabits seems to be reaching out to destroy him. Like Peter Lorre’s hunted child killer in Fritz Lang’s M (1931), the film seems to take the criminal’s perspective and, despite his crimes, we cannot resist empathizing with him—in the same way we might feel watching a putrid rat approach a trap and begin to nibble on cheese.

Although the first-half’s tight, enclosed structure demonstrated Kurosawa’s visual ingenuity with elegant close-quarters blocking, the second half finds his production shooting in cramped police conference rooms and on location in shady nightclubs and slums. In a quasi-verité style that recalls Kurosawa’s own Stray Dog (1949), the director’s handheld cameras take to crowded city streets teeming with everyday citizens, yakuza gang members, drug dealers, and prostitutes. The second-half could also be considered strange because the basic plot is over; the kidnapped boy was returned home. All that remains is catching the kidnapper, which is less about vengeance or retribution for Gondo than the duty of justice for the police. Nevertheless, the procedural elements of High and Low serve its greater purpose. When the film takes Takeuchi’s perspective, the scenes appear more like film noir, complete with grim shadows and light peering through narrow openings. Takeuchi becomes a doomed character similar to Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity (1944) or Robert Mitchum in Out of the Past (1947)—he made a bad decision, and now the aesthetic structure of the film he inhabits seems to be reaching out to destroy him. Like Peter Lorre’s hunted child killer in Fritz Lang’s M (1931), the film seems to take the criminal’s perspective and, despite his crimes, we cannot resist empathizing with him—in the same way we might feel watching a putrid rat approach a trap and begin to nibble on cheese.

After the authorities catch Takeuchi and sentence him to death for killing his accomplices, the kidnapper requests to meet Gondo before his ultimate penalty. Separated only by glass and cage wire, Takeuchi confesses to looking up at Gondo’s house from the slums below. As Takeuchi explains, he began to resent Gondo’s wealth and soon hated looking up at the house. At this, Gondo, who, having advanced from a shoemaker to a production executive, and who has always worked hard to build something greater than himself, says, “Why do we have to hate one other?” Kurosawa frames the shot so Gondo and Takeuchi sit across from one another, separated by glass, but also mirrored by one another. Gondo built himself up from nothing and, though tempted by greed and selfishness, made the correct moral decisions in the end. It is only their choices that separate Gondo from Takeuchi, not their social, class, or financial status. They are both “condemned,” as Martin Scorsese once remarked about the film, with being human. Gondo’s understanding and blameless sensibility only enrages Takeuchi more, leaving the kidnapper ashamed of his own anger. The film ends as guards take Takeuchi away. Gondo sits alone.

High and Low was based on a pulpy American novel called King’s Ransom by author Ed McBain. Kurosawa found himself attracted to the story not only because of its unique structural elements, but also because of the material’s potential social commentary. Published in 1959, McBain’s book was adapted in 1962 for a U.S. television series called 87th Precinct, a weekly program that McBain helped develop, though it lasted just a single season. But Kurosawa had read McBain’s book in 1961, and Toho, the director’s home studio, purchased the film rights for $5,000. Along with his frequent writing collaborators Hideo Oguni, Eijiro Hisaita, and Ryuzo Kikushima, Kurosawa adapted the material beyond the text, changing it to include far more substance. For instance, McBain’s novel ends with the shoe executive recovering both his son and money, allowing him to close the deal to secure National Shoes. Additionally, the executive in McBain’s story catches the kidnapper himself, solidifying his status as the book’s hero. By ending his film, which finds Gondo penniless save for his new job, the film suggests that human life is defined not by social hierarchies, but rather what a person decides to do within the seemingly random situation fate has chosen to bestow upon them. Whereas McBain wrote a standard kidnapping thriller, Kurosawa advances the story into a timeless reflector of social stratification.

High and Low was based on a pulpy American novel called King’s Ransom by author Ed McBain. Kurosawa found himself attracted to the story not only because of its unique structural elements, but also because of the material’s potential social commentary. Published in 1959, McBain’s book was adapted in 1962 for a U.S. television series called 87th Precinct, a weekly program that McBain helped develop, though it lasted just a single season. But Kurosawa had read McBain’s book in 1961, and Toho, the director’s home studio, purchased the film rights for $5,000. Along with his frequent writing collaborators Hideo Oguni, Eijiro Hisaita, and Ryuzo Kikushima, Kurosawa adapted the material beyond the text, changing it to include far more substance. For instance, McBain’s novel ends with the shoe executive recovering both his son and money, allowing him to close the deal to secure National Shoes. Additionally, the executive in McBain’s story catches the kidnapper himself, solidifying his status as the book’s hero. By ending his film, which finds Gondo penniless save for his new job, the film suggests that human life is defined not by social hierarchies, but rather what a person decides to do within the seemingly random situation fate has chosen to bestow upon them. Whereas McBain wrote a standard kidnapping thriller, Kurosawa advances the story into a timeless reflector of social stratification.

Then again, Kurosawa’s film explores a theme more universal than even social position, as evidenced by the original Japanese title, Tengoku to Jigoku, meaning “Heaven or Hell,” which as Kurosawa’s biographer Donald Richie suggests, offers an “extreme opposite that merely High and Low does not.” The director does not attribute highness to Heaven nor lowness to Hell, at least regarding a social scale. Instead, the film judges its characters by their actions, by Gondo’s morally correct decision to pay the ransom for his chauffer’s son, and by Takeuchi’s crimes of kidnapping the boy and murdering his accomplices. Indeed, the film offers two outwardly polarized opposites and blurs the distinctions between them. The slums, where “It’s hot as hell… An inferno, 105 degrees,” serve as a kind of underworld populated by heroin addicts and whores, though nightclubs and city streets are also populated with decent people. And yet, the slum hardly seems as treacherous as Gondo’s expensive and luxurious home atop the hill. It may appear idyllic from Takeuchi’s perspective, but Kurosawa portrays this so-called heaven as a place where ruthless executives make shady deals and betray loyalties—all for higher revenues. Although their circumstances may be different, Gondo and Takeuchi are very much the same. Kurosawa presents a tragedy in that only Gondo recognizes this sameness, whereas Takeuchi clings to his pride and envy.

Japan’s postwar growth created a catastrophic socioeconomic gap. And while Takeuchi could be considered both a victim of this gap and his death sentence, Kurosawa seems to argue that every person is responsible for their choices. Through the unique structure of High and Low, Kurosawa examines how the hierarchy of newly established social statuses has resulted in a gulf between human beings, and from that, a lack of personal responsibility. Although disguised as a kidnapping thriller, High and Low finds Kurosawa searching for answers to the reasons people separate themselves from one another. The film serves as a mirror to contemporary Japan, helping his audience recognize that their social status does not remove or even strengthen their basic humanity. He considers a culture of social ladders to be an unfortunate barrier, and an obsolete one in matters of right and wrong or simple compassion for one’s fellow human beings. He views the class system as a filter similar to the glass and cage wire separating Takeuchi and Gondo in the film’s final scene, in that classes needlessly keep people apart.

Japan’s postwar growth created a catastrophic socioeconomic gap. And while Takeuchi could be considered both a victim of this gap and his death sentence, Kurosawa seems to argue that every person is responsible for their choices. Through the unique structure of High and Low, Kurosawa examines how the hierarchy of newly established social statuses has resulted in a gulf between human beings, and from that, a lack of personal responsibility. Although disguised as a kidnapping thriller, High and Low finds Kurosawa searching for answers to the reasons people separate themselves from one another. The film serves as a mirror to contemporary Japan, helping his audience recognize that their social status does not remove or even strengthen their basic humanity. He considers a culture of social ladders to be an unfortunate barrier, and an obsolete one in matters of right and wrong or simple compassion for one’s fellow human beings. He views the class system as a filter similar to the glass and cage wire separating Takeuchi and Gondo in the film’s final scene, in that classes needlessly keep people apart.

In Japan, High and Low was widely praised as a masterpiece and earned around $1.3 million to become the highest-grossing film of 1963. Internationally, however, Kurosawa’s reputation had grown relatively commonplace, and Western critics began to take him for granted, describing him as merely a formalist. According to a Sight and Sound evaluation from the time, Kurosawa “is of very little interest” as a thinker. But such trivializing remarks only demonstrate a surface level appreciation of Kurosawa’s genius. How could the filmmaker behind Rashomon (1950), Ikiru (1952), and Seven Samurai (1954) be accused of a lack of existential, intertextual, or social conditions in his films? Most Western critics did not understand High and Low‘s relevance in Japan, nor Kurosawa’s structural conceit, nor could they understand why Kurosawa thought so-called “lower” material from the crime genre would resonate. Several critics lauded the film’s technical aspects but dismissed its emotional power or social conscience. Writers for Variety, Newsweek, and The New Republic each met the film with a balance of admiration for the actors and procedural elements, while they also censured the film’s structure and meaning. Nevertheless, history would prove High and Low to be recognized as one of Kurosawa’s most esteemed works. Martin Scorsese even planned a remake with Universal Studios in the early 1990s, but due to several kidnapping thrillers released around the same time, such as Ron Howard’s Ransom (1996), the project was shelved indefinitely.

High and Low continues to draw viewers and film historians because of Kurosawa’s lasting humanism and desire for understanding between people. All contrary notions of heaven and hell, good and evil, or heroes and villains dissolve in the film in favor of something intermingled and byzantine, the way people are. Such polarizations are made equal through the ways in which Gondo and Takeuchi resemble one another through their shared ambitions, and how, given a few distinct choices, their lives could have been more like the other’s. Having directed thirty films in a career over fifty years long, Kurosawa remains not just a Japanese master filmmaker, but a filmmaker whose thematic perspective questions the reasons people the world over remain divided. “I suppose all of my films have a common theme,” he once wrote, explaining that his films seek to answer the question “Why can’t people be happier together?” To explore this question, Kurosawa tells stories about disjointed worlds and characters trying to find ways to adjust and maintain their identity. His ongoing investigation is, perhaps more than any other filmmaker, that of an artist who brings other cultures together through a universally human question.

High and Low continues to draw viewers and film historians because of Kurosawa’s lasting humanism and desire for understanding between people. All contrary notions of heaven and hell, good and evil, or heroes and villains dissolve in the film in favor of something intermingled and byzantine, the way people are. Such polarizations are made equal through the ways in which Gondo and Takeuchi resemble one another through their shared ambitions, and how, given a few distinct choices, their lives could have been more like the other’s. Having directed thirty films in a career over fifty years long, Kurosawa remains not just a Japanese master filmmaker, but a filmmaker whose thematic perspective questions the reasons people the world over remain divided. “I suppose all of my films have a common theme,” he once wrote, explaining that his films seek to answer the question “Why can’t people be happier together?” To explore this question, Kurosawa tells stories about disjointed worlds and characters trying to find ways to adjust and maintain their identity. His ongoing investigation is, perhaps more than any other filmmaker, that of an artist who brings other cultures together through a universally human question.

Bibliography:

Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: Norton & Company, 1999.

Galbraith IV, Stuart. The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. New York: Faber and Faber, 2002.

Goodwin, James. Akira Kurosawa and Intertextual Cinema. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.

McDonald, Keiko I. Reading a Japanese Film: Cinema in Context. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; annotated edition, 2006.

Richie, Donald. The Films of Akira Kurosawa, Third Edition, Expanded and Updated. With additional material by Joan Mellen. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1996.

Richie, Donald; Schrader, Paul. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha International: Distributed in the U.S. by Kodansha America, 2005.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review