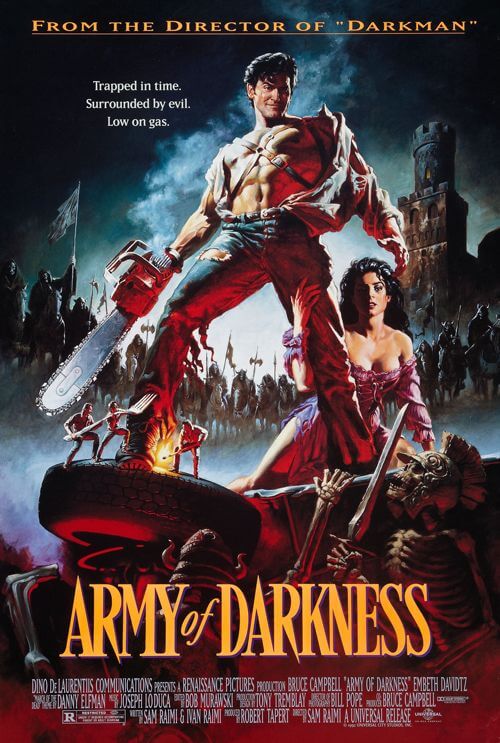

Army of Darkness

By Brian Eggert |

Mark Twain’s novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, published in 1889, follows industrialist Hank Morgan as he’s mysteriously transported back in time to the Middle Ages, where his knowledge of future technologies earns him a place beside Merlin, who views Morgan as a kind of magician. Sam Raimi’s Army of Darkness, the third film in his Evil Dead series, uses Twain’s book as a springboard for a wacky comic adventure teeming with film references galore. Both works share a humorous dynamic where modern know-how clashes with the backward past, and an ancient culture is confounded by a “man out of time.” Moving his series tone away from its origins of pure, bone-chilling horror and into physical comedy, Raimi engages in a full embrace of his love for classic cinema through satire, resulting in a film that’s not scary or particularly thrilling but just plain fun. Filled with wacky humor and enough homage to make cinephiles giddy, Army of Darkness is also a special FX showcase and features an especially enduring comedic performance from series star Bruce Campbell.

Picking up where its predecessor Evil Dead 2 (1987) left off, Army of Darkness begins when Campbell’s chainsaw-armed S-Mart employee and Deadite-killer Ash is sucked through a time vortex and lands in 1300 AD, only to find himself shackled in the court of Arthur (Marcus Gilbert). At first believed to be an ally of Arthur’s opponent Duke Henry the Red (Richard Grove), a Wiseman (Ian Abercrombie) suggests Ash may be the “Chosen One” foretold to protect their people from the Deadite scourge. Proving his salt, Ash goes on a quest to retrieve the Necronomicon—a book containing the incantations needed not only to send Ash back to his time but to stop the Deadites. During his journey, Ash is confronted by an evil Deadite force that gets inside him to create a doppelganger, a twin called Evil Ash (also Campbell). After quickly disposing of his twin, Good Ash botches up the special words that must be said when obtaining the Necronomicon, and he inadvertently releases the Deadite evil. Unearthed is the titular army led by none other than the zombified Evil Ash, who marches on Arthur’s castle in a climactic battle. Seemingly victorious over evil, Good Ash is sent back to his own time to the Housewares department of S-Mart, where he’s suddenly attacked by a lone Deadite. He kills the thing, claims a somewhat random doting female onlooker for a kiss, and the film ends with our hero boasting.

After Evil Dead 2 earned backer Dino De Laurentiis a profit, the producer offered to help finance a third chapter in Raimi’s series. In the interim, Raimi teamed with Universal Studios for Darkman (1990), a superhero film modeled from the classic horror picture The Phantom of the Opera, and had written a screenplay for a third Evil Dead film with his brother, Ivan. Pleased with Darkman, Universal offered to split the budget of Army of Darkness, which proved much larger than its predecessors because the story’s scale abandoned the cabin-in-the-woods setup. Regardless of an increased scope, everyone involved in the first two took pay cuts and the crew consisted of non-union workers to stretch their funding. The story contained skeleton battles, medieval armor, castle and windmill sets, horses, and plenty of practical makeup—but every dollar of the budget shows up onscreen. To complete the time-consuming stop-motion animation skeleton fight sequences, Raimi and his crew innovated on a Ray Harryhausen technique to improve the quality of the live-action and stop-motion elements by front projecting the image with the actor, making them appear on the same plane. Campbell suffered a grueling series of takes, sometimes more than thirty, to achieve the exact timing required to make these shots work. For the climactic battle sequences, Raimi used unique, dramatic angles in the skeleton’s attack on the castle walls, later inspiring Peter Jackson to use almost carbon-copied shots for The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002).

Shooting nearly two months of principal photography, Raimi relied on his hands-on approach to realize the demanding screenplay. Many scenes required several overlapping elements at once, including a live-action component (Campbell), a mechanical component such as a skeleton, and then a stop-motion element or visual effect. Such complex sequences required exhaustive storyboarding. But no matter how extensively Raimi planned out their technical shoot, Universal remained unhappy with the first cut, particularly the ending. Much like Evil Dead 2, the Raimi brothers’ original screenplay ended Army of Darkness with a cliffhanger to set up a sequel. Instead of returning to the present-day, Ash drinks the Wiseman’s sleeping potion, bungles the magic words, and oversleeps to awaken in the London of a post-apocalyptic future. A hilarious downer-of-an-ending, the twist fits perfectly with the conclusions of its forerunners, but Universal wasn’t laughing. They found the concept too downbeat, forcing one to speculate if anyone at the studio had ever seen one of Raimi’s Evil Dead films. Nevertheless, with funds running out, Raimi shot the theatrical, more optimistic conclusion that finds Ash in S-Mart, saving the day once more. Although seemingly more upbeat, upon reflection it’s still a downer, insomuch that Ash may have stopped his evil twin, but the Deadites clearly weren’t defeated in 1300 AD.

Shooting nearly two months of principal photography, Raimi relied on his hands-on approach to realize the demanding screenplay. Many scenes required several overlapping elements at once, including a live-action component (Campbell), a mechanical component such as a skeleton, and then a stop-motion element or visual effect. Such complex sequences required exhaustive storyboarding. But no matter how extensively Raimi planned out their technical shoot, Universal remained unhappy with the first cut, particularly the ending. Much like Evil Dead 2, the Raimi brothers’ original screenplay ended Army of Darkness with a cliffhanger to set up a sequel. Instead of returning to the present-day, Ash drinks the Wiseman’s sleeping potion, bungles the magic words, and oversleeps to awaken in the London of a post-apocalyptic future. A hilarious downer-of-an-ending, the twist fits perfectly with the conclusions of its forerunners, but Universal wasn’t laughing. They found the concept too downbeat, forcing one to speculate if anyone at the studio had ever seen one of Raimi’s Evil Dead films. Nevertheless, with funds running out, Raimi shot the theatrical, more optimistic conclusion that finds Ash in S-Mart, saving the day once more. Although seemingly more upbeat, upon reflection it’s still a downer, insomuch that Ash may have stopped his evil twin, but the Deadites clearly weren’t defeated in 1300 AD.

When an additional $3 million was required to complete reshoots, Universal used Raimi’s need as a bargaining chip to secure a piece of De Laurentiis’ rights to the popular Hannibal Lecter character. De Laurentiis had produced Michael Mann’s Manhunter (1986) and also the hugely successful, five-time Academy Award winner The Silence of the Lambs (1991). Universal stalled any further funding on Army of Darkness for a piece of De Laurentiis’ other franchise. When De Laurentiis conceded (laying the groundwork for 2000’s Hannibal), Universal finally forked over the supplementary funds. Furthermore, Universal demanded additional cuts that reduced Raimi’s version (length: 96 minutes) to a scarce 81-minute runtime. When all the trimming and later reshoots were completed, the theatrical cut left everything not directly related to the Deadite plot on the cutting room floor. Even scenes required for story logic were trimmed. Among the notable exclusions were a scene between Campbell and Embeth Davidtz that developed Ash’s romantic interest and a sequence explaining why Henry the Red suddenly shows up to assist his nemesis Arthur in the finale.

Army of Darkness opened on February 19, 1993, to much confusion, not only from critics but from fans of the series expecting a horror movie. Even more confusing was the film’s unnecessary R-rating, given its cartoonish, almost Monty Python and the Holy Grail-type quality. Raimi had effectively “sold out” according to die-hard horror enthusiasts, whereas a few critics appreciated Raimi’s evident film history knowledge, in-film references, and his ability to make classic cinematic trickery at once impressive yet funny. The title alone confused moviegoers, who had no idea Army of Darkness was a follow-up to The Evil Dead and Evil Dead 2. Perhaps the proposed title Medieval Dead or even simply Evil Dead 3 would have been more fitting. Years later on video, where the “director’s cut” has appeared, videophiles still struggle to find a quality version of Army of Darkness. Some releases have restored Raimi’s original ending and expanded 96-minute runtime but sacrificed video quality for the added content, whereas the best-looking editions contain the theatrical cut only. Amid the “Boomstick Edition,” “Screwhead Edition,” “Official Bootleg Edition,” and countless others, it still remains impossible to find a suitably mastered DVD or Blu-ray of Raimi’s original vision of Army of Darkness.

Army of Darkness opened on February 19, 1993, to much confusion, not only from critics but from fans of the series expecting a horror movie. Even more confusing was the film’s unnecessary R-rating, given its cartoonish, almost Monty Python and the Holy Grail-type quality. Raimi had effectively “sold out” according to die-hard horror enthusiasts, whereas a few critics appreciated Raimi’s evident film history knowledge, in-film references, and his ability to make classic cinematic trickery at once impressive yet funny. The title alone confused moviegoers, who had no idea Army of Darkness was a follow-up to The Evil Dead and Evil Dead 2. Perhaps the proposed title Medieval Dead or even simply Evil Dead 3 would have been more fitting. Years later on video, where the “director’s cut” has appeared, videophiles still struggle to find a quality version of Army of Darkness. Some releases have restored Raimi’s original ending and expanded 96-minute runtime but sacrificed video quality for the added content, whereas the best-looking editions contain the theatrical cut only. Amid the “Boomstick Edition,” “Screwhead Edition,” “Official Bootleg Edition,” and countless others, it still remains impossible to find a suitably mastered DVD or Blu-ray of Raimi’s original vision of Army of Darkness.

This is a shame, since downer endings and a beleaguered Ash are what the Evil Dead films are all about. The final sequence in Evil Dead 2 where Ash, transported back to 1300 AD, realizes that he’s the fabled hero from the Necronomicon who, as he points out earlier, “didn’t do a very good job” in defeating the evil, is a hilarious disgrace. Our hero has never been a spotless source of chivalrousness; he’s a joke—a nincompoop whose posturing and impressive equipment (be it chainsaw arm, robotic hand, gunpowder, or an Oldsmobile Delta 88 souped-up with a deadly propeller) isn’t matched by his effectiveness. Rather than the prophesied heroic defender from the Deadites, Ash is a complete boob. He’s an often heroic but in-the-end-hopeless protagonist who’s arrogant and sarcastic (“Well hello Mister Fancypants… I’ve got news for you pal, you ain’t leadin’ but two things, right now: Jack and shit… and Jack left town.”) Throughout his adventures, he delivers empty threats by shaking his fist or degrades the Medieval people (an entire civilization of “straight man” characters) with jabs they couldn’t possibly understand. He’s not exactly admirable, but he’s hilarious and charming nonetheless, and easier to relate to as a modern character in a period setting. His behavior doesn’t warrant a victory, which is why Raimi’s original ending would have been fitting. As is, the theatrical ending is serviceable—funny, but not aligned with those of its predecessors.

Fortunately, Raimi’s complete immersion into film references could not be denied by Universal, and in fact, this quality is what Army of Darkness thrives on. The original post-apocalyptic ending recalls the conclusion of The Planet of the Apes (1968), a personal favorite of the director, and Campbell’s version of Ash in Army of Darkness even seems modeled after Charlton Heston’s likewise “man out of time” character. When the Wiseman directs Ash not to misspeak the passage “Klaatu Verata Nikto,” sci-fi fanatics will recognize these lines from The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951). Raimi’s use of Harryhausen effects stems from wonders like The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963), and the sword fights on stairways recall Errol Flynn’s bounding in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Raimi’s love of the Three Stooges guides the entire tone of the film. Larry, Curly, and Moe skeletons appear, as well as a Stooge slapstick routine and eye-pokes when Ash tangles with dozens of skeletons in the graveyard. It’s impossible to believe Raimi didn’t have the medieval-themed Stooge films Restless Knights (1935) and Squareheads of the Round Table (1948) in mind while filming. But Raimi’s references are not solely cinematic; they’re literary, as suggested by the correlation between the film and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. There’s also a nod to Gulliver’s Travels when a dozen tiny Ash clones tie our hero down to the ground.

Fortunately, Raimi’s complete immersion into film references could not be denied by Universal, and in fact, this quality is what Army of Darkness thrives on. The original post-apocalyptic ending recalls the conclusion of The Planet of the Apes (1968), a personal favorite of the director, and Campbell’s version of Ash in Army of Darkness even seems modeled after Charlton Heston’s likewise “man out of time” character. When the Wiseman directs Ash not to misspeak the passage “Klaatu Verata Nikto,” sci-fi fanatics will recognize these lines from The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951). Raimi’s use of Harryhausen effects stems from wonders like The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963), and the sword fights on stairways recall Errol Flynn’s bounding in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Raimi’s love of the Three Stooges guides the entire tone of the film. Larry, Curly, and Moe skeletons appear, as well as a Stooge slapstick routine and eye-pokes when Ash tangles with dozens of skeletons in the graveyard. It’s impossible to believe Raimi didn’t have the medieval-themed Stooge films Restless Knights (1935) and Squareheads of the Round Table (1948) in mind while filming. But Raimi’s references are not solely cinematic; they’re literary, as suggested by the correlation between the film and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. There’s also a nod to Gulliver’s Travels when a dozen tiny Ash clones tie our hero down to the ground.

Broad slapstick humor, innumerable references to other films, and above all, Campbell’s presence as a physical comedian and sarcastic jerk single out Army of Darkness as a unique experience from its predecessors. Some may consider this a negative quality—that this third entry isn’t the gore-fest it should have been, and therefore doesn’t “fit”—but the film also stands alone as an entertaining adventure-comedy, one where Campbell shows a completely different side of himself in a largely comic performance. Cheesy one-liners and quotable dialogue (“Alright you Primitive Screwheads, listen up! You see this? This is my boomstick!”) make repeated viewings a joy, and the franchise’s enduring success is marked with cult enthusiasm for this installment in particular. Watching the trilogy all together, it’s not difficult to see Army of Darkness as the odd man out next to The Evil Dead and Evil Dead 2. What came before was far more original and daring, even more so for its low-budget, independent ingenuity, and genre-blending uniqueness. And yet, this sequel does exactly what Raimi has always done by taking other films and filtering them through his own distinctive style and approach, resulting in a project that cannot be accurately compared to anything before or since, and that remains silly fun.

Bibliography:

Campbell, Bruce. If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor. LA Weekly Books for St. Martin’s Press, 2001.

Muir, John Kenneth. The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2004.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review