Trance

By Brian Eggert |

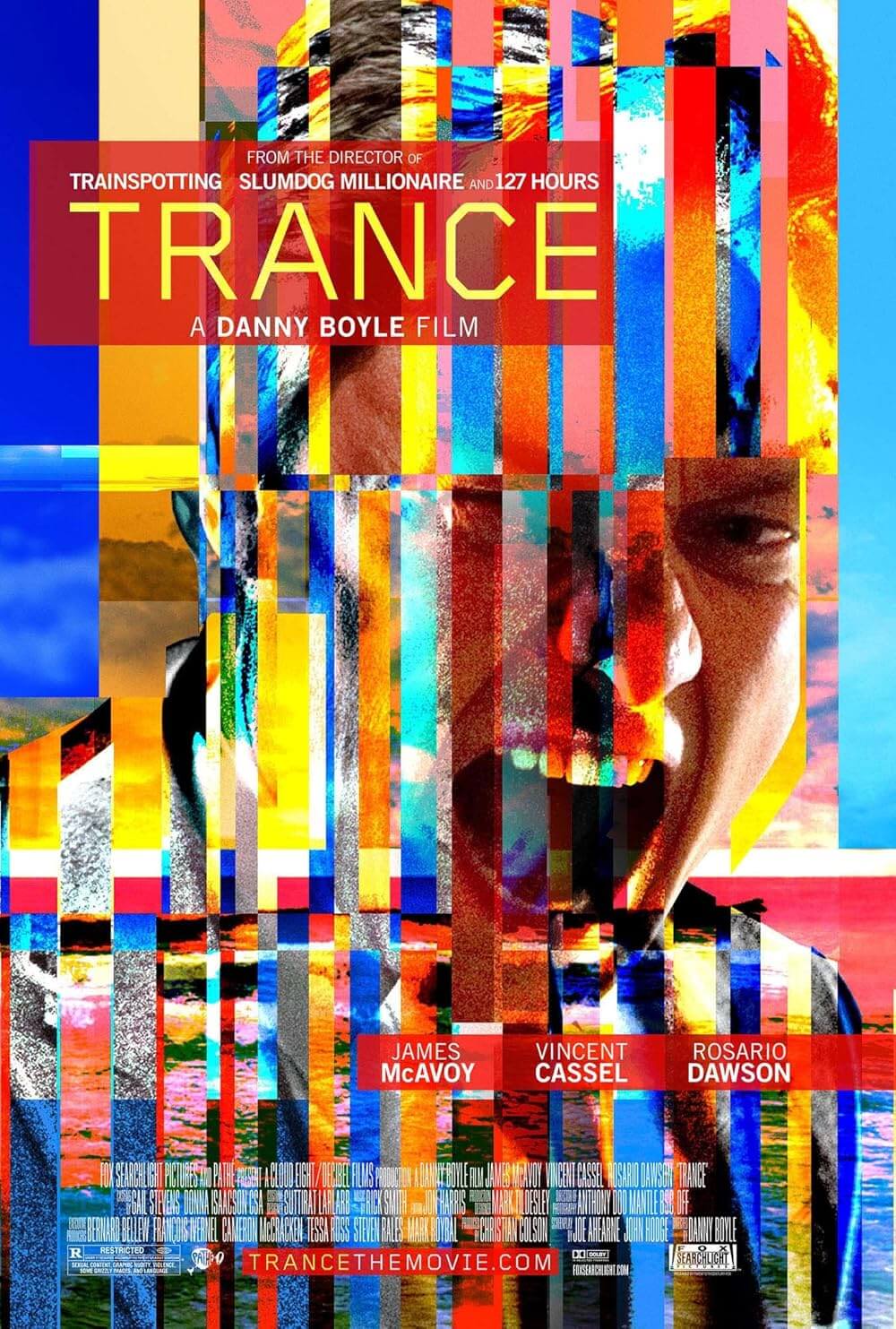

Within the first few scenes of Danny Boyle’s Trance, the viewer becomes aware they’re being manipulated by a mind-bending plot and a director who’s enjoying the hell out of playing us. Boyle’s enthusiasm for the material makes it easy to willingly go where he takes us, because his visual style pops with energy, yet it never feels superficial, and his actors portray characters whose layers we’re anxious to see peeled back. Inside a twisting scenario about an art-heist-gone-wrong is Boyle’s more fascinating trip inside unconscious minds and damaged psyches, how he develops the complex psychological makeup of his characters. All the while, we’re aware that just around the corner, some revelatory turn in the story will change everything we’ve learned thus far, and that for much of the film, we will feel disoriented and misdirected. This we must accept, just as we must accept that the final explanation of our enduring question (What’s going on?) could not possibly be as satisfying as the journey there.

For much of the first and even second act, Trance looks and feels like a standard heist yarn about an auctioneer, Simon (James McAvoy), who helps a band of mid-level crooks steal a priceless Goya from a London auction house. During the robbery, head thief Franck (Vincent Cassel, intimidating but likable) delivers a blow to Simon’s head, and, after the fracas settles, he realizes Simon didn’t follow the plan. The painting is missing, but where? Simon can’t remember; he’s now a legitimate amnesiac, and not even Franck’s torture will encourage total recall. Enter hypnotherapist Elizabeth Lamb (Rosario Dawson), picked seemingly at random out of a local listing. She’s tasked with poking around in Simon’s head to determine what happened during the art heist, but the moment she first sees Simon, she hesitates. She seems to know Simon but doesn’t say anything. Quickly established as coolly in control, Elizabeth wants a piece of the painting too, and, because Franck has no other choice, he concedes to her strict demands in order to find his loot. Elizabeth begins sessions with Simon, but soon Franck and his three-man crew must get involved as well.

At times the film seems to disappear completely inside Simon’s head, where it’s unclear what’s real and what’s a projection of his subconscious. McAvoy maintains our sympathies even when his motivations become suspect; we never want him to be the character he’s revealed to be, but as Elizabeth keeps digging, Simon just gets worse and worse. Fortunately, McAvoy has the talent to make each new version of Simon believable. Frequent scenes where Simon suddenly wakes from hypnosis or a nightmare might be inconsequential in another thriller of this kind, but Boyle and his screenwriter Joe Ahearne (who also wrote the 2001 TV movie on which Trance was based) embed hidden clues inside those dreams, hinting at both the characters and the central mystery of the missing Goya. In other words, watch carefully and, once it’s all over, watch it again to catch what you’ve missed. In standard Boyle fashion, every frame dazzles with stylish use of color and oddball angles, but his method never advocates style over substance. There’s always something sly or meaningful under the surface. Art enthusiasts alone have much to relish, as the symbolism of classical nudes contrasted by modernist revision has a major role in defining the characters and the circumstances that unfold as the film goes on.

Just consider the apartments of Simon and Elizabeth. When we first see Simon’s home, it’s been trashed by Franck’s crew during their search for the Goya. Simon’s belongings have been strewn about, art books ripped apart and painting prints hanging crookedly from the walls. The mess reflects the fragmented and unruly Simon, whose passions reside in frantic emotions and passionate obsessions, and it says something about the character that he never bothers to clean up the mess as the film progresses. Simon’s obsessions become his crux as their complexity deepens further into Trance in monstrous and frightening ways best discussed after a viewing. And now consider Elizabeth’s contemporary apartment, whose interior walls are lined with orange neon glass in geometric shapes, everything carefully compartmentalized, much like the character herself. Be they represented through interior design or the contrast of classical and modern nudes, Boyle builds these characters in ways that allude to their inner makeup, yet he leaves aspects of them a mystery to shock us at key turns in the story.

If Boyle’s other films threatened to over-stimulate timid viewers, Trance may seem like overkill in style to those who found Trainspotting, Slumdog Millionaire, or 127 Hours excessive. Shockingly violent and intensely erotic, the not-always-linear presentation employs strong imagery to explore the characters’ deep-rooted issues and suppressed memories, with editor Jon Harris cutting through dream sequences and hypnotic suggestions to create illusory, dreamlike connections between them. Keeping up with how the plot progresses is sometimes an exercise in abstract thinking. The way it’s pieced together is outdone only by the careful consideration of the images themselves. One aerial shot of a winding system of glowing red highway bridges and roads at night recalls the brain’s flowing synapses without the director having to hint at the visual connection; he lingers on the image just long enough for us to make the association on our own. Boyle is nothing if not bold, but he’s also a thoughtful visualist. He shot the film over two years, some before he directed the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympics and some after, using his frequent cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, who’s lensed nearly all of Boyle’s films since 28 Days Later.

If the film happens to have some unfortunate exposition during the third act to explain what’s come before, these moments are more than overshadowed by the director’s overall visual audacity and the psychological intricacy of the characters. It’s the kind of picture where as soon as it’s over, you’re thinking back to what happened earlier and what clues you no doubt missed—and without a doubt, you missed something. Boyle densely packs every frame with metaphoric imagery and kinetic technique that to consume every detail would be impossible in just one viewing. This is the kind of film review I regret having to write after a single screening, and I regret having to avoid exploring in more detail to indulge the reader’s general aversion to spoilers. More than the plot itself is the trio of central characters, so absorbing in their motivations and secrets, and so effectively acted. Much like Steven Soderbergh did with this year’s Side Effects, Boyle elevates the mechanics of a somewhat standardized thriller with characters that remain intriguing to the last and an elevated degree of style. It’s like his first feature, 1994’s Shallow Grave, in that respect, as it’s about a group of isolated characters in a suspenseful cat-and-mouse game. The first time we watch it to find out what happens; the second and subsequent times, we watch for the density and bravura of everything onscreen.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review