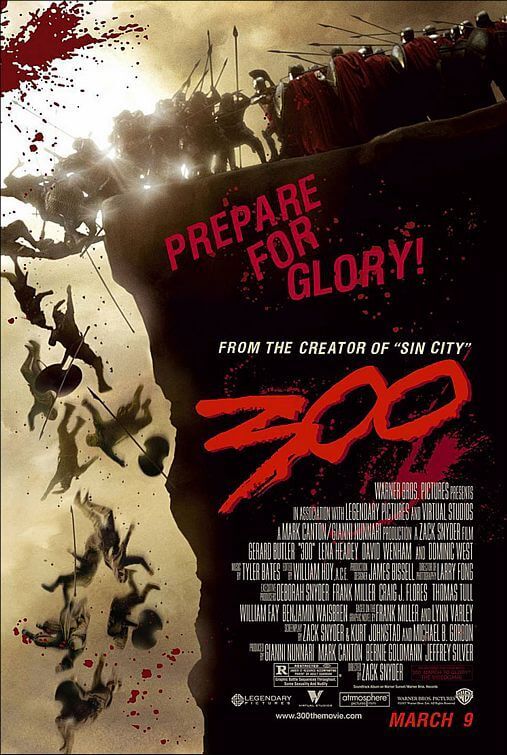

300

By Brian Eggert |

Frank Miller’s bloody graphic novel 300 receives a film adaptation akin to his own Sin City thanks to filmmaker Zack Snyder, the director of the actionized 2004 remake Dawn of the Dead. The story derives its foundation from the Spartan Battle of Thermopylae in which, for three days, 300 Spartan soldiers defended a mountain pass from an onslaught of a couple of thousand Persians. The plot and the atmosphere of the film are that of a comic book: bending reality, like Sin City, with strange creatures and fantastic landscapes. Snyder shot 300 entirely in front of blue screens; the backgrounds and most of the picture’s settings are computer generated. Painterly and impossibly grandiose environments reflect the film’s comic origins, but the innovative visuals, while notably creative, are not enough to compensate for the lackluster, often laughably bad dialogue and screen story.

A militaristic Dorian state of Greece, Sparta was a reclusive and mysterious society that has gathered many speculative analyses from historians. Because of Sparta’s cloistering attitude toward foreign spectators, little evidence survives to illuminate who these people were. Far away from where Greek historians could ever see, Spartan customs were at the very least known to be expertly violent and bent on isolation and independence. Laws, customs, and historical documents were prohibited to maintain secrecy. Homer’s Iliad briefly mentions the Spartans, but as to the day-to-day goings on of Sparta, we rely on guesswork based on what little evidence exists. Because we have so few facts, the historical gap allowed Miller to invent a Sparta that suited authoristic drives. He chooses a side of polarized historical debates to make his Sparta a masculine paradise. He accentuates the maleness of Spartan warriors to fit his own penchant for masculine storytelling. In doing this, he ignores what little we do know about ancient Sparta for his own purposes. It’s not the disregard for facts I have a problem with, as any period film misrepresents historical detail in some form or another. I have a problem with how Miller continually twists history to tell blatantly sexist stories.

Miller’s chauvinist views often come through in his work; normally I might look past such motifs as a part of the story, but how can one disregard such an apparent trend from this writer? His take on noirish narratives in Sin City (which was made into a pulpy and vibrant comic noir film by Robert Rodriguez in 2005) exemplified dark, smoky narration and bleak city atmosphere, but his male characters were all violent killers, and his women were mostly prostitutes. In 300, the women of Miller’s Sparta are said to have prideful strength but are conversely used as bargaining chips or sexual toys by the men. Miller forgets that one of the only truths we know about ancient Sparta is that women had most of the power, owned land, and controlled the throne. Miller turns his Spartan Queen (Lena Headly) into a whore to further the plot; she is weakened and victimized by a man, never to regain her credibility as a strong female within the context of the film. She remains the old cliché: just a woman.

Miller’s male characters are not only violent and war-driven, but they’re also blatantly heterosexual. King Leonidas (played by Gerard Butler) comments on the people of Greece, poking fun at their homosexual affairs. What little (and debatably authentic) evidence we do have on Sparta shows that young Spartan warriors were often mentored by older warriors; the relationship is sometimes noted as homosexual in nature. Varying sources claim the opposite: that Spartans were notoriously, in comparison to Greeks, heterosexual. In either case, the polarized argument exists, and Miller chose to represent his males as wholly heterosexual to further his masculine take on the material. The film’s homophobia and sexism don’t end there. Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro), the god-king of the Persians, is represented as a seven-foot man, effeminate in posture. He sports painted eyebrows, eyeliner, and golden facial makeup. Leonidas, who maintains a fuming war face throughout the picture, only lets up his glower twice in the film. The first instance is with his wife and child at the beginning of the film; the second instance is with Xerxes. Coming face-to-face with his enemy on the battlefield to discuss conditions, Leonidas turns his back on the god-king. Xerxes approaches from behind for appeal and gently rests his hands on Leonidas’ shoulders; the Spartan king’s eyes lighten for a moment as if Xerxes has mortally penetrated Leonidas through such a delicate touch. The scene reeks of homoeroticism—something Leonidas is clearly uncomfortable with.

Ironically, though, the film appears to be weighted in masculine hubris, many of the camaraderie scenes between the 300 Spartans come off as homoerotic. The scantily clad warriors virtually dance with one another as they mow down their enemies, chop off heads, and dart spears across the battlefield. The story also seems to embrace pro-war attitudes, which if applied to modern-day politics, comes off as somewhat Republican. The disregard for homosexuality also supports this theory. Spartan kings were said to descend from Heracles and were more like generals than sitters of the throne. The film’s Leonidas is given a ferocious appetite for male stubbornness and rushes to war rather than finding a political solution. Who knows if Miller or Zack Snyder intended Sparta to look like the present-day U.S., rushing off to battle on a whim, but one cannot deny the possibility of the argument. (It’s worth noting that Persia is contemporary Iran).

When the 300 Spartans fight, the battle scenes are filmed with a combination of slow motion and accelerated camera speeds—the zoom moving in and out at random. Glorifying the numerous decapitations and splatters of CGI-created blood, the director’s camera moves so that the audience cannot help but acknowledge the apparatus—the camera—actually plays a significant role in the picture. I kept thinking, why is Snyder zooming so randomly? Why does he slow down the swordplay, then Swoosh, speed it up again? I was distracted by the director’s incapability of simply letting the beauty of his computer-generated world unfold. Instead, we’re meant to ogle blood like a Peeping Tom looking into a bedroom window. As a result, the film feels as though it’s only meant to appeal to young, juvenile males with a view of violence that equals the reality of a video game.

The one redeeming quality of the film is the picturesque beauty of certain landscapes, primarily the work on clouds and atmosphere. The blue screen-shot film appears wholly stylized, and like Sin City, is visually awe-inspiring. In one scene, an oracle girl convulses in and out of slow motion, her transparent and lace-thin gown and hair flowing amidst swirls of incense smoke. Scenes like this show the possibility of the blue screen medium; others, such as the Queen’s proposal to the council, reveal the over-used sense of heavy light—rays of sun gleaming through the columns are almost tangible and are certainly clumsy. Also clumsy is the writing, chiefly the constant and unnecessary narration, which sounds like something two six-year-olds might recite to each other while playing war in the backyard. I must have heard “For Sparta!” fifty times in two hours. At times, I felt like every line of dialogue derived from better movies such as Gladiator and Braveheart.

300 claims some impressive visuals, but the narrow-mindedness of the plot and the childishness of the writing made this film hugely disappointing. Perhaps this review’s arguments about the film’s lack of historical accuracy are inappropriate given the graphic novel source material. Perhaps it’s silly to dwell on the thinly developed Spartan government and sexual politics when the intent of the film is clearly a visceral, pointedly visual experience. Perhaps it was a mistake to hope the film’s intellectual stimuli would match its visual stimuli. But to truly enjoy 300, the viewer is required to switch off their brain and concentrate only on aesthetics. The trouble is, this isn’t the Silent Era, and we’re doing more than watching. The film’s dialogue and narration are painstakingly corny and over-the-top, making the rest of the film, no matter how visually imposing, impossible to enjoy on any meaningful level. Although an admittedly gorgeous experience, Snyder’s film is ultimately an empty one.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review