The Definitives

Sweet Smell of Success

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Sidney Falco, a pilot fish press agent, hovers around his meal ticket, bloodthirsty shark J.J. Hunsecker, the powerful gossip columnist. Seated at his regular table in the 21 Club, Hensecker shares dinner with a senator, a blonde hooker, and the agent who functions as a social buffer between these dinner guests. Sidney calls the table and asks to join them. Hunsecker’s voice replies, “No, you’re dead, son. Get yourself buried.” Sidney has failed Hunsecker in a crucial task, and now he must grovel to earn another shot. His career on the block, Syndey marches in anyway and stands himself beside and almost behind Hunsecker. Without looking at Sidney, Hunsecker addresses the senator, and, with airs of great precision and menace, speaks indirectly to Syndey: “Harvey, I often wish I were deaf and wore a hearing aid. With a simple flick of a switch, I could shut out the greedy murmur of little men.”

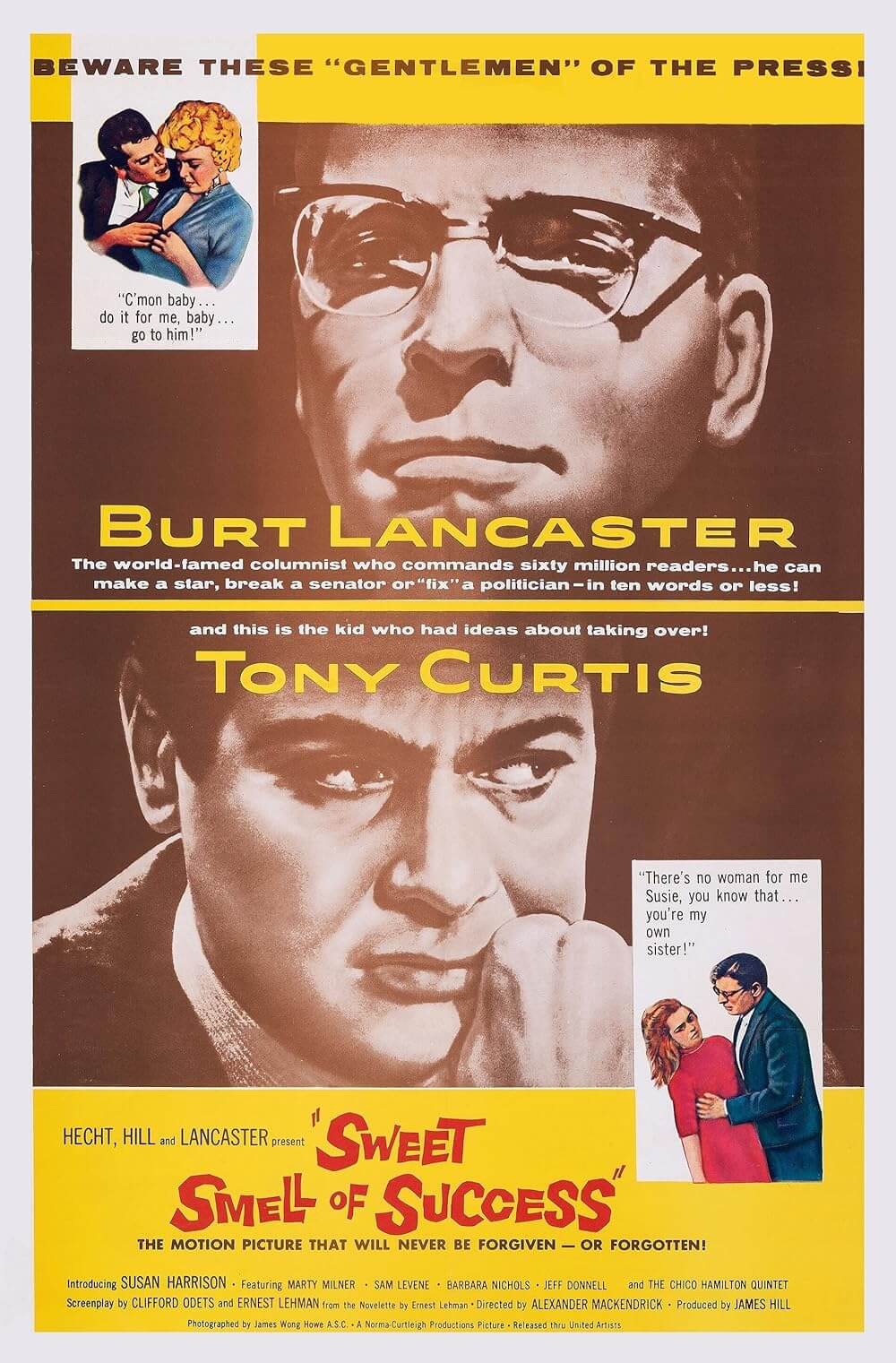

Sweet Smell of Success replaces shootouts with verbal ricochets, affirming, both on and offscreen, that when the words are dagger-sharp, the pen remains mightier than the sword. A hard spotlight on the trickery of media culture, namely the reign of the prevailing 1930s to 1950s gossip columnist Walter Winchell, the 1957 film embraces the melodramatic flourishes of an atmospheric film noir. Alexander Mackendrick directs scenes driven by ruthless dialogue, bold acting, and incredible camerawork, his usual craftsmanlike direction elevated by the film’s inventive blocking and expressive tone. Screenwriter Charles Odets, working from the novella and first draft screenplay by Earnest Lehman, creates acid-tongued dialogue delivered by verbal sparring partners Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis. James Wong Howe’s rich black-and-white location photography evokes the corruption and seediness in the New York City backdrop’s Broadway theaters and posh nightclubs. And the entirety is set to Elmer Bernstein’s bluesy score that, performed by Chico Hamilton’s jazz Quintet, echoes the grimy moral ambivalence of the characters within.

Released during the decline of cinema’s Golden Age and amid HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) witchhunts, the film defied media moguls of the period and scoffed in the face of capitalist powers in a time when anti-establishment thinking brought suspicion. With witty scorn whose insolence entertains, few films have such unlikely Hollywood origins, yet many that took the same risks as Sweet Smell of Success, with time, became treasures of the cinema. Regardless of the film’s box-office failure and initially mixed reception, time has allowed the picture’s reputation to grow. Winchell’s reign deteriorated after the film’s release and authority shifted away from those in power who took offence, thus it became easier and safer to openly identify and support the wonders of the film’s harsh but comic cynicism. Critics and filmmakers alike began to reassess the picture: The Coen Brothers, Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Steven Steven Soderbergh have all made homage to or spoken out on the film’s influence on their own work. Today it can be listed among the greatest of all film noirs, yet unique in that its subject rests in the very remote microcosm of its two main characters.

Released during the decline of cinema’s Golden Age and amid HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) witchhunts, the film defied media moguls of the period and scoffed in the face of capitalist powers in a time when anti-establishment thinking brought suspicion. With witty scorn whose insolence entertains, few films have such unlikely Hollywood origins, yet many that took the same risks as Sweet Smell of Success, with time, became treasures of the cinema. Regardless of the film’s box-office failure and initially mixed reception, time has allowed the picture’s reputation to grow. Winchell’s reign deteriorated after the film’s release and authority shifted away from those in power who took offence, thus it became easier and safer to openly identify and support the wonders of the film’s harsh but comic cynicism. Critics and filmmakers alike began to reassess the picture: The Coen Brothers, Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Steven Steven Soderbergh have all made homage to or spoken out on the film’s influence on their own work. Today it can be listed among the greatest of all film noirs, yet unique in that its subject rests in the very remote microcosm of its two main characters.

In this cruel world of a film, sycophantic press agent Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis) has been outcast by powerful gossip columnist J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster), whose opinions can make or break everyone from entertainers to politicians. Sidney is so comparably insignificant that a handwritten sign reading his name is taped to his office door, and inside that door is his apartment. Sidney was instructed by Hunsecker to break up the relationship between his sister, Susie Hunsecker (Susan Harrison) and jazz musician Steve Dallas (Martin Milner). Having failed, Sidney’s groveling earns him a second chance, as Hunsecker seems to goad him when he holds up a cigarette and drops the film’s most memorable line: “Match me, Sidney”—a request with a double meaning, both an order and a challenge. Sidney later promises: “The cat’s in the bag and the bag’s in the river.” In his wheeling and dealing to satisfy Hunsecker, Sidney convinces a humiliated and fearful cigarette girl Rita (Barbara Nichols) to bed a competing columnist so that he might print a story that would ruin Dallas. The next morning, the newspaper accuses Dallas of being a marijuana user and card-carrying communist.

While Sidney waits in Hunsecker’s office for his pat on the head, the secretary confronts him, as various parties throughout the film often do: “There isn’t a drop of respect in you for anything alive… You’re too immersed in the theology of making a fast buck.” Sidney’s sole purpose throughout the film remains elevating himself from a lowly press agent to a powerful media figure like Hunsecker. He admits, “J.J. Hunsecker is the golden ladder to the place I want to get.” And in working the Hunsecker obstacle to the top, Sidney endures no end of public humiliations and seemingly constant emasculations by his idol, among them threats, to where even Susie recognizes that Sidney is treated like a “trained poodle”. In brief moments where Curtis shows Sidney’s regret and makes him pitiable, he captures the film’s implication that civilization has been overrun by notions of celebrity, money, and power—in other words, by Success.

While Sidney waits in Hunsecker’s office for his pat on the head, the secretary confronts him, as various parties throughout the film often do: “There isn’t a drop of respect in you for anything alive… You’re too immersed in the theology of making a fast buck.” Sidney’s sole purpose throughout the film remains elevating himself from a lowly press agent to a powerful media figure like Hunsecker. He admits, “J.J. Hunsecker is the golden ladder to the place I want to get.” And in working the Hunsecker obstacle to the top, Sidney endures no end of public humiliations and seemingly constant emasculations by his idol, among them threats, to where even Susie recognizes that Sidney is treated like a “trained poodle”. In brief moments where Curtis shows Sidney’s regret and makes him pitiable, he captures the film’s implication that civilization has been overrun by notions of celebrity, money, and power—in other words, by Success.

Sidney’s plan ultimately backfires, however; Dallas assumes that only Sidney and Hunsecker could have planted the erroneous story and confronts Sidney. Hunsecker agrees to meet with Dallas and Susie to discuss their future, and there he plays the duplicitous role of a concerned brother and asks Dallas if the charges are true. The conversation erupts and Dallas insults Hunsecker—“You and your slimy scandal, your phony patriotics… To me, Mr. Hunsecker, you’re a national disgrace!”—which allows him to tell Susie never to see “that boy” again. Sidney seems to have won Hunsecker’s approval, as they sit together at his table at 21, enjoying a pricey meal. But it seems Hunsecker’s victory was not enough; personally insulted by Dallas’ slight, he tells Sidney that he wants Dallas “taken apart”. Sidney proceeds by planting marijuana cigarettes on Dallas, and then informing on him to a crooked cop, Lieutenant Harry Kello (Emile Meyer), loyal to Hunsecker.

Overwhelmed by guilt after watching Dallas arrested, Sidney stops to order a drink and toasts, with false enthusiasm, “To my favorite new perfume: Success!” During the toast, he receives a call to report to Hunsecker at his decadent penthouse apartment high above the city. When Sidney arrives, he finds Susie in a slip, heartbroken over Dallas and talking of suicide; she makes for the terrace to jump, but Sidney stops her and throws her on the bed. Hunsecker enters at the perfect moment to misread the situation, and it becomes apparent that Susie has organized this confrontation between Hunsecker and Sidney. Faced with Hunsecker’s harsh glare and accusatory tone, Sidney tries to explain why his hands were on Susie. When that fails, he defends himself in front of Susie and attempts to push back, openly accusing Hunsecker of orchestrating Dallas’ arrest. Hunsecker calmly calls his muscle, and, for his aspirations and scheming, Sidney faces brutal film noir punishment offscreen. Susie, meanwhile, sees through her brother’s false concern and ignores his threat of sending her to “a good psychoanalyst” for her attempted suicide. She tells him “I’d rather be dead than living with you” and leaves. In the last scenes, Susie walks into the warm dawn light free of her brother, who remains perched on a dark balcony and looks down high above the city.

Overwhelmed by guilt after watching Dallas arrested, Sidney stops to order a drink and toasts, with false enthusiasm, “To my favorite new perfume: Success!” During the toast, he receives a call to report to Hunsecker at his decadent penthouse apartment high above the city. When Sidney arrives, he finds Susie in a slip, heartbroken over Dallas and talking of suicide; she makes for the terrace to jump, but Sidney stops her and throws her on the bed. Hunsecker enters at the perfect moment to misread the situation, and it becomes apparent that Susie has organized this confrontation between Hunsecker and Sidney. Faced with Hunsecker’s harsh glare and accusatory tone, Sidney tries to explain why his hands were on Susie. When that fails, he defends himself in front of Susie and attempts to push back, openly accusing Hunsecker of orchestrating Dallas’ arrest. Hunsecker calmly calls his muscle, and, for his aspirations and scheming, Sidney faces brutal film noir punishment offscreen. Susie, meanwhile, sees through her brother’s false concern and ignores his threat of sending her to “a good psychoanalyst” for her attempted suicide. She tells him “I’d rather be dead than living with you” and leaves. In the last scenes, Susie walks into the warm dawn light free of her brother, who remains perched on a dark balcony and looks down high above the city.

Today’s literal-minded audiences might miss barbed notions embedded into the title, but 1957’s audiences read the sardonic phrasing therein—the adjective “sweet” as in ‘ripe’, and the noun “smell” as in ‘offensive odor’—as a vulgar allusion to pungent feces. Pair those words along with “success” and the cruel lessons of the picture emerge in alliterative splendor. And if moviegoers did not realize this beforehand, they certainly learned the lesson by the film’s finale. Sweet Smell of Success was the original title for Lehman’s novella first published in Cosmopolitan in 1950, but upon request of the magazine’s editor, who did not want the word “smell” with all its associations appearing in his magazine, the writer agreed to change the title to Tell Me about It Tomorrow! Only later when Lehman’s novella was republished to promote the film was the original title restored. Lehman’s inspiration for Hunsecker, gossip columnist Walter Winchell, was known throughout as “W.W”, much as everyone calls Hunsecker as “J.J.” in the film. Earning a name for himself by covering the Lindbergh kidnapping, Winchell embraced celebrity culture and made Hollywood careers by merely mentioning a name. He was known to keep a table at the Stork Club on Broadway, where he would hold important meetings at late hours. After becoming one of the first in the American media to publically oppose Nazism, his political ties gave him extraordinary power as a voice of radio and print authority. That power was later used as a McCarthy-era anti-communist weapon to spread his suspicious agenda.

Winchell bore what some believed was an abnormal fixation on his daughter, Walda; he threatened to shoot anyone who became romantically entangled with her. When Walda became engaged to Broadway producer William Cahn, Winchell applied his influence to ruin Cahn’s career and later, using his friendship with J. Edgar Hoover, had Cahn arrested for tax evasion. Eventually, Cahn escaped to Israel, but in 1947, Winchell had Walda examined by psychiatrists and declared incompetent, all to preserve his authority over his daughter. In the film, Hunsecker’s parental control over his sister could also suggest the behavior of a jealous would-be lover, hinting at the incestuous undertones between Winchell and Walda. Mackendrick shoots Lancaster as a towering figure over Harrison, always protecting her with eerie sincerity and insisting he only has her best interests at heart. Hunsecker speaks softly to Susie in a fatherly tone, referring to her as “dear” and cutting her off when speaking on her behalf. One of the great traits of the film is how Mackendrick empowers Susie in the end, giving her control and allowing her to escape from Hunsecker’s rein in a way that Walda never could.

Winchell bore what some believed was an abnormal fixation on his daughter, Walda; he threatened to shoot anyone who became romantically entangled with her. When Walda became engaged to Broadway producer William Cahn, Winchell applied his influence to ruin Cahn’s career and later, using his friendship with J. Edgar Hoover, had Cahn arrested for tax evasion. Eventually, Cahn escaped to Israel, but in 1947, Winchell had Walda examined by psychiatrists and declared incompetent, all to preserve his authority over his daughter. In the film, Hunsecker’s parental control over his sister could also suggest the behavior of a jealous would-be lover, hinting at the incestuous undertones between Winchell and Walda. Mackendrick shoots Lancaster as a towering figure over Harrison, always protecting her with eerie sincerity and insisting he only has her best interests at heart. Hunsecker speaks softly to Susie in a fatherly tone, referring to her as “dear” and cutting her off when speaking on her behalf. One of the great traits of the film is how Mackendrick empowers Susie in the end, giving her control and allowing her to escape from Hunsecker’s rein in a way that Walda never could.

After Lehman published his novella, Winchell’s top Hollywood gossip reporter, Irving Hoffman, who was also a friend to Lehman, took offense, believing that if Hunsecker was based on Winchell, then the slimy Sidney Falco must be based on Hoffman. Lehman claimed that he did not intend for such a connection, rather he just explored the natural underworld of media industry—where “some people killed others with words instead of bullets”. For more than a year, Hoffman held a grudge against the writer until a mutual friend convinced him to forgive and forget. Doing much more, Hoffman allowed Lehman to use a column in The Hollywood Reporter for a piece suggesting what a fine screenwriter Lehman would make. Of course, Lehman wrote the piece himself under a ghost name, praising his own authenticity for stories about New York City nightlife. Within two years of that article’s publication in 1952, Lehman’s credits could be seen on the films Executive Suite and Sabrina, and in the coming decade North by Northwest and West Side Story.

But before Lehman’s novella was optioned, the Production Code Administration deemed the work objectionable for the implied incestuous relationship onscreen, the appearance of marijuana as a framing device, and the suggestion of an unpunished murder in the finale. Furthermore, any projects with notably dark or cynical themes were bound to draw attention from HUAC, resulting in the talent involved being potentially blacklisted for their involvement. This, along with fear of retaliation from a still very powerful Winchell, and a dramatic decline in movie theater ticket sales with the emergence of television, left a risky project such as Lehman’s story clouded by a miasma of certain danger and financial ruin for the investing studio. Still, from this climate of fear surfaced independent studios backed by some of Hollywood’s top brass who had since abandoned the studio system to eke out their own productions for major profits. One such an independent outfit was Lancaster’s own Hecht-Hill-Lancaster (HHL), originally called Norma Productions (named after Lancaster’s wife), but later changed to include his partners, theatrical agent Harold Hecht and former MGM screenwriter James Hill.

But before Lehman’s novella was optioned, the Production Code Administration deemed the work objectionable for the implied incestuous relationship onscreen, the appearance of marijuana as a framing device, and the suggestion of an unpunished murder in the finale. Furthermore, any projects with notably dark or cynical themes were bound to draw attention from HUAC, resulting in the talent involved being potentially blacklisted for their involvement. This, along with fear of retaliation from a still very powerful Winchell, and a dramatic decline in movie theater ticket sales with the emergence of television, left a risky project such as Lehman’s story clouded by a miasma of certain danger and financial ruin for the investing studio. Still, from this climate of fear surfaced independent studios backed by some of Hollywood’s top brass who had since abandoned the studio system to eke out their own productions for major profits. One such an independent outfit was Lancaster’s own Hecht-Hill-Lancaster (HHL), originally called Norma Productions (named after Lancaster’s wife), but later changed to include his partners, theatrical agent Harold Hecht and former MGM screenwriter James Hill.

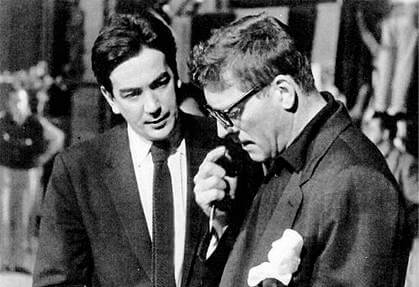

When Lehman’s novella was optioned by HHL for distribution by United Artists, the uncertain times of the early 1950s were calming to a dull roar, and this decline in political paranoia was the ideal moment to strike. Fond of his novella and hoping to advance his career, Lehman signed a deal with HHL to adapt Sweet Smell of Success on the condition that he direct. But the abrasive tendencies of Lancaster, an aggressive personality, womanizer, and hardnosed businessman, took over. Lehman wanted Orson Welles for the role of Hunsecker, if only to echo Welles’ fictional role of a real-life media figure in Citizen Kane, but Lancaster decided he would play Hunsecker himself. Lancaster’s domineering personality took over Lehman’s inexperience as a director, and then Lehman was fired as director by Hecht and offered a producer role instead. In addition to scouting actual New York locations for the shoot, Lehman’s first role as producer was hiring his replacement, Alexander Mackendrick.

Mackendrick, a Boston-born American of Scottish parents, has been confused as a British director for having earned his notoriety under England’s Ealing Studios, where he made witty comedies such as Whiskey Galore and The Man in the White Suit. He grew up in Glasgow and attended Glasgow School of Art, where he learned advertising to later become a commercial illustrator. After directing a number of commercials, he moved on to filmmaking for nine years with Ealing. In 1955, he completed The Ladykillers starring Alec Guinness, a commercial and critical success that brought him to Hollywood to direct an adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s The Devil’s Disciple for HHL, the project that was set aside for Sweet Smell of Success. He would later walk away from his fading career as director to become a renowned instructor at the California Institute of the Arts, where he taught principles presented in his posthumously published book On Filmmaking: An Introduction to the Craft of the Director. With his background in advertising and having dabbled in tabloid journalism, Mackendrick brought the same talent he had employed on The Ladykillers for exploiting complex schemes through character-driven storytelling, except with that melodramatic edge and heavy stylization inherent to film noir.

Mackendrick, a Boston-born American of Scottish parents, has been confused as a British director for having earned his notoriety under England’s Ealing Studios, where he made witty comedies such as Whiskey Galore and The Man in the White Suit. He grew up in Glasgow and attended Glasgow School of Art, where he learned advertising to later become a commercial illustrator. After directing a number of commercials, he moved on to filmmaking for nine years with Ealing. In 1955, he completed The Ladykillers starring Alec Guinness, a commercial and critical success that brought him to Hollywood to direct an adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s The Devil’s Disciple for HHL, the project that was set aside for Sweet Smell of Success. He would later walk away from his fading career as director to become a renowned instructor at the California Institute of the Arts, where he taught principles presented in his posthumously published book On Filmmaking: An Introduction to the Craft of the Director. With his background in advertising and having dabbled in tabloid journalism, Mackendrick brought the same talent he had employed on The Ladykillers for exploiting complex schemes through character-driven storytelling, except with that melodramatic edge and heavy stylization inherent to film noir.

Lehman, ordered on vacation by his doctor to cure his rampant anxiety (brought about by Lancaster’s often turbulent, even sometimes violent working environment), left his producing duties to James Hill and the screenplay rewrites to HHL writer Clifford Odets. A playwright whose cynical views on success in America, and whose first-hand experience on Broadway included face time with Winchell himself, Odets’ work as a screenwriter was not as prolific as his plays. In 1952, he gave HUAC names of suspected communists in Hollywood, and his shame over that testimony permeated in him a raging distrust of the establishment, specifically those like Winchell and McCarthy (the latter dies just a few weeks before the film’s release). Yet, Odets reworked Lehman’s script over multiple versions, preserving Lehman’s plot and only a few lines of the original dialogue, while adding priceless quips and stylized language of his own.

Much like Casablanca in how it was a work-in-progress until shooting wrapped, the end result of Odets’ script feels no less cohesive for its assorted incarnations on the page. The rewrites were so extensive and so frequent that cast and crew were known to wait on set as Odets punched out new pages on his typewriter. He toyed with the narrative’s structure, reformatting the story into a non-linear tale with flashbacks, and even inserted explanatory narration; both experiments were eventually scrapped. Through Odets’ efforts, Lehman’s script was disassembled and restructured, the entire story imbued with greater tension in each scene, every moment entangled with the next. Odets infused crucial subplots and dramatic relevance to every character, leaving the final product a singularly constructed piece of storytelling, despite the oftentimes disjointed feeling of scripts that have been reworked again and again by various writers and producers.

Much like Casablanca in how it was a work-in-progress until shooting wrapped, the end result of Odets’ script feels no less cohesive for its assorted incarnations on the page. The rewrites were so extensive and so frequent that cast and crew were known to wait on set as Odets punched out new pages on his typewriter. He toyed with the narrative’s structure, reformatting the story into a non-linear tale with flashbacks, and even inserted explanatory narration; both experiments were eventually scrapped. Through Odets’ efforts, Lehman’s script was disassembled and restructured, the entire story imbued with greater tension in each scene, every moment entangled with the next. Odets infused crucial subplots and dramatic relevance to every character, leaving the final product a singularly constructed piece of storytelling, despite the oftentimes disjointed feeling of scripts that have been reworked again and again by various writers and producers.

Filmed on location in New York City, cinematographer James Wong Howe shot the picture in gorgeous black-and-white photography that highlights the city’s nightlife in its best theaters and restaurants. As one of Hollywood’s most enduring and celebrated cameramen, Howe’s filmography, spanning fifty years beginning in the 1920s and lasting until 1975, reads like a list of cinema’s best: he worked with directors like Michael Curtiz, Raoul Walsh, Howard Hawks, John Frankenheimer, and Samuel Fuller. Howe was also a monumental innovator; he created dollies for fluid camera movements and employed dynamic yet natural lighting which seemed to amplify reality. Take the scene in 21, where an overhead table lamp gleams down to cast a shadow of Lancaster’s glasses on his face, making Hunsecker look scaly and inhuman in the moment. Ricocheting dialogue bounces back and forth in this scene and Howe’s camerawork never misses a moment, as he follows Mackendrick’s expert blocking to create an atmosphere of tense emotions and turbulent exchanges.

Though Lehman infused his screenplay with stylized language both deliberately theatrical yet guttural in its intention (even the title bears Lehman’s satirical touch), the film’s best lines can be attributed to Odets. Among the lines celebrated on several “best” lists is Hunsecker’s remark to Falco: “I’d hate to take a bite outta you. You’re a cookie full of arsenic.” The ornate language combines almost elegiac witticisms filled with bitter imagery and verbiage worthy of then-modern newspapermen (“Don’t remove the gangplank, Sidney. You may wanna get back onboard.”). The dialogue suggests a twisted version of His Girl Friday, filled with the same humor and expressive exaggeration, but with a brutality that echoes the film’s merciless tone (“Son, I don’t relish shooting a mosquito with an elephant gun, so why don’t you just shuffle along?”). Watching, it becomes easy to imagine Glengarry Glen Ross playwright and House of Games director David Mamet developing his signature caustic style for “Mametspeak” from here, as well as his penchant for dialogue-driven cinema. Note Odets’ speeches, so literary in their winding vulgarity; they carry on without missing a beat. Both monologues and exchanges blaze with unmatched speed that much of the film’s greatness resides in the dialogue alone, making any discussions of the film pointless without dozens of quotations.

Though Lehman infused his screenplay with stylized language both deliberately theatrical yet guttural in its intention (even the title bears Lehman’s satirical touch), the film’s best lines can be attributed to Odets. Among the lines celebrated on several “best” lists is Hunsecker’s remark to Falco: “I’d hate to take a bite outta you. You’re a cookie full of arsenic.” The ornate language combines almost elegiac witticisms filled with bitter imagery and verbiage worthy of then-modern newspapermen (“Don’t remove the gangplank, Sidney. You may wanna get back onboard.”). The dialogue suggests a twisted version of His Girl Friday, filled with the same humor and expressive exaggeration, but with a brutality that echoes the film’s merciless tone (“Son, I don’t relish shooting a mosquito with an elephant gun, so why don’t you just shuffle along?”). Watching, it becomes easy to imagine Glengarry Glen Ross playwright and House of Games director David Mamet developing his signature caustic style for “Mametspeak” from here, as well as his penchant for dialogue-driven cinema. Note Odets’ speeches, so literary in their winding vulgarity; they carry on without missing a beat. Both monologues and exchanges blaze with unmatched speed that much of the film’s greatness resides in the dialogue alone, making any discussions of the film pointless without dozens of quotations.

Granted, it takes incredible timing and talent to deliver such lines with the correct rhythm and inflection, and Sweet Smell of Success features two of the period’s best actors in their most potent performances, in roles lovable for their unlovable qualities. Lancaster no doubt attracted to the role of Hunsecker after realizing it was “a star vehicle”—in that Hunsecker is referenced and built-up by the other characters long before he appears onscreen, leaving both Lancaster and Hunsecker to ride the already considerable tidal wave. By the time Hunsecker is introduced, Lancaster towers onscreen like a monolith, reinforcing the character’s feared reputation with those icy blue eyes and every double-edged line. In many cases, the short-tempered actor and producer channeled his offscreen rage into his performance, making this a particularly barbed portrayal from an actor by and large identified by his intensity. And, though Lancaster looked nothing like the short and bald Winchell, a chatty man known for his philandering, his angular physique and rigid expressions personify Winchell’s power.

Tony Curtis’ impalpable charisma as Sidney Falco recalls Kirk Douglas’ performance in Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole or Richard Widmark in Night and the City—a performance that transcends what is shown onscreen and a character that oddly demands the audience’s pity, though his motivations dwell in “moral twilight” and his methods are often disgraceful. Curtis’ restless performance has him rushing from here to there to get his angle, talking fast and scheming faster, backed by his charming good looks and underdog appeal. And though Falco displays despicable behavior, Curtis has a strange ability to convey sympathetic vulnerability in his presence alone, whereas another actor might have failed to gather the audience’s sympathies. Perhaps Falco remains sympathetic simply because Hunsecker proves so much more appalling and contemptible. Or, perhaps Curtis has that indefinable quality to make his characters likable no matter how little background is provided or how few redeemable traits they exhibit.

Tony Curtis’ impalpable charisma as Sidney Falco recalls Kirk Douglas’ performance in Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole or Richard Widmark in Night and the City—a performance that transcends what is shown onscreen and a character that oddly demands the audience’s pity, though his motivations dwell in “moral twilight” and his methods are often disgraceful. Curtis’ restless performance has him rushing from here to there to get his angle, talking fast and scheming faster, backed by his charming good looks and underdog appeal. And though Falco displays despicable behavior, Curtis has a strange ability to convey sympathetic vulnerability in his presence alone, whereas another actor might have failed to gather the audience’s sympathies. Perhaps Falco remains sympathetic simply because Hunsecker proves so much more appalling and contemptible. Or, perhaps Curtis has that indefinable quality to make his characters likable no matter how little background is provided or how few redeemable traits they exhibit.

Curtis’ talent aside, audiences accustomed to seeing the teen heartthrob in lighter fare like Houdini and The All American recoiled against the morally questionable behavior of Sidney Falco, and his frankly unattractive role. Such reactions caused the film to flop at the box-office, which left Winchell to revel over its failure in his column. Even so, Lehman claims to have seen Winchell skulking across the street at the film’s premiere, suggesting the filmmakers had (successfully) struck a personal chord with the columnist. Critics wrote of their dismay that Sweet Smell of Success offers no characters to which audiences can relate, outside of its in some ways, humorous cruelty. Preview screenings left viewers vocal with antipathy toward the picture, whereas its most vocal detractors at The Christian Science Monitor felt the film bore too much “pleasure in its disgust”. Yet, more respectable critiques from Time and high profile film journals like Sight & Sound, though uncommon in their high evaluation of the film, saw the sophistication behind Mackendrick’s Broadway melodrama, and with their lasting assessments, the film has grown into a classic of cynical cinema.

Through Sidney Falco and J.J. Hunsecker’s symbiotic relationship so deficient of morals, Sweet Smell of Success remains a picture about publicity and media only on the surface. When Hunsecker remarks with sleazy confidence “I love this dirty town,” Odets’ words brim over with social and political subtext to reveal a much larger target: The America Way, with all of its incestuous, power hungry, self-defacing ambitions. However, such poison-lipped distrust cannot undermine the film’s many pleasured kisses: Odets’ whiplash dialogue, the plot’s scandalous machinations, Curtis and Lancaster’s crackling performances, and Mackendrick’s continuous cinematic bluster. These elements each further the incendiary purpose behind this masterpiece and demand one look on with awe at how such a delightfully corrosive film like this was ever made in Hollywood.

Bibliography:

Gabler, Neal. Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity. New York: Vintage, 1994.

Mackendrick, Alexander. On Filmmaking: An Introduction to the Craft of the Director, ed. Paul Cronin. New York: Faber and Faber, 2004.

Naremore, James. Sweet Smell of Success. London: British Film Institute, 2010.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review