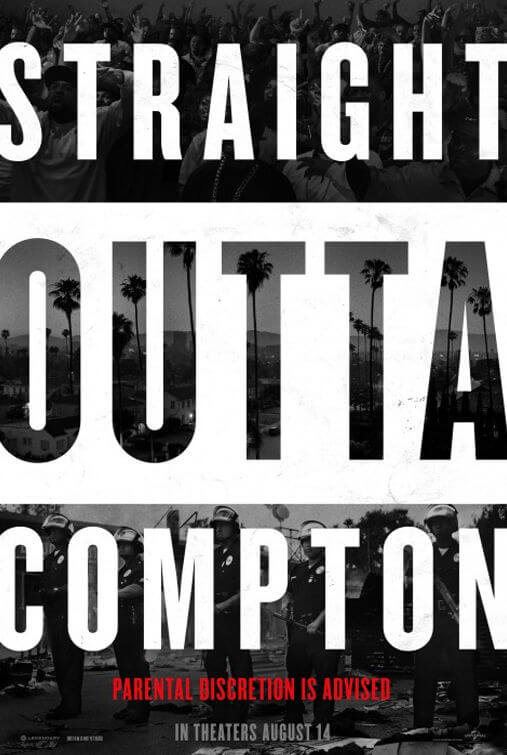

Straight Outta Compton

By Brian Eggert |

When the first N.W.A. album hit the streets in 1988, hip-hop forever changed from an artform centralized in the East Coast to a national, if not West Coast-leaning genre. “Gangsta rap” was born from the streets of Los Angeles and reverberated on the airwaves, echoing the feelings and experiences of thousands of youth listeners. Director F. Gary Gray’s multi-tiered biopic Straight Outta Compton adopts the N.W.A. (“Niggaz With Attitude”) debut album name, and with it signals a timely revival of “reality rap”—the group’s preferred name for their style. Just as Public Enemy’s albums Yo! Bum Rush the Show (1987) and It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988) were racially charged and seemed to channel their generation, N.W.A. arrived around the same time and resulted in even more controversy. Their biting and graphic lyrics became nationally recognized, and its members helped articulate the feelings of African Americans in a tumultuous time in U.S. history, intensified by the Rodney King beating and subsequent L.A. riots. While showcasing their social influence, the film also frames N.W.A.’s talent in a standard musical biography template.

Covering a period between 1986 to 1993, the film completely disregards several negative episodes from the lives of the N.W.A. performers—aside from the late Eric “Easy-E” Wright (played by Jason Mitchell), whose death allows the filmmakers certain artistic freedoms. Ice Cube and Dr. Dre helped produce Straight Outta Compton, and not-so-aggrandizing moments in their lives (such as Dre’s multiple arrests for violence against women) are altogether ignored to maintain their current, respectable image: Cube has since become the lovable star of mostly bad, broad movies, and Dre earns millions from his Beats headphones. There’s also limited attention paid or background given to N.W.A. members DJ Yella and MC Ren, played by Neil Brown Jr. and Aldis Hodge. And yet, the film delivers a subplot involving Dre’s partnership with the infamous Suge Knight (R. Marcus Taylor) and Death Row Records’ artists Tupac Shakur and Snoop Dogg. This is to be expected, not just because Cube and Dre are producers, but because the biographical simplification of musicians’ lives to a few landmark moments is a common practice for the genre.

The film opens in 1986 with an intense Compton dope deal, where Easy-E narrowly escapes a violent police raid on a dealer’s house, planting the seed that maybe the thug life isn’t for him. Elsewhere, a young Andre “Dr. Dre” Young (Corey Hawkins) moves out of his mother’s house to focus on his DJ career and writing beats. Dre’s friend, O’Shea “Ice Cube” Jackson (O’Shea Jackson Jr., son of Cube) writes the lyrics and delivers his hardcore rap style to enthused crowds at early gigs. Before long, Dre asks Easy-E to invest in what becomes the Ruthless record label, and their first single “Boyz-n-the-Hood”, sung by an initially reluctant Easy-E, sells like hotcakes. But according to former rock manager Jerry Heller (Paul Giamatti), they need someone with business acumen to become “legit” and, with Easy-E heading Ruthless, Heller gets them a deal with Priority Records. Eventually, Heller borders on becoming a white Jewish stereotype, ensuring his own financial needs are taken care of before the group, but the script offers Heller more than one dimension.

As their Straight Outta Compton album arrives in 1988 with the Cube-penned song “Fuck tha Police”, it creates a response from various authorities—including a threatening letter from the FBI and some lousy tactics by the Detroit Police Force. The film’s representation of race relations in America makes Gray’s film powerful stuff, at least during the first half. Police brutality and racial profiling served as a springboard for the N.W.A.’s most popular songs. This is evidenced in a disturbing scene where the entire group is shaken down by some Torrance cops who denigrate not only their appearance as “gangbangers” but rap itself. Heller’s defense of his group’s integrity is one of Giamatti’s better moments in the film. Gradually, the film loses momentum as Ice Cube leaves because he believes, correctly, that Heller is more concerned about his own income than the artists’. After a battle between Cube’s solo efforts and the N.W.A.’s later albums, Dr. Dre splits to begin a rocky collaboration with Suge Knight. Easy-E is left alone with Ruthless, full of regret, financial troubles, and hoping for an N.W.A. reunion—all before discovering he’s going to die of HIV in a memorializing finale.

In a sense, the first half of Straight Outta Compton couldn’t be timelier, tapping into the sense of racial injustice as modern-day demonstrators protest against police tactics in Ferguson, Cleveland, Baltimore, and New York. But screenwriters Jonathan Herman and Andrea Berloff shy away from issues that are either just vaguely addressed or not addressed at all. During a press conference, a reporter asks the group how they respond to accusations that their lyrics glorify violence. Cube responds, “Our art is a reflection of our reality.” To be sure, half of “Fuck Tha Police” describes racial profiling and abuses of authority by the LAPD, but the other half talks about going on a cop-killing “warpath” with sniper rifles, AK-47s, and Uzis. The film doesn’t really acknowledge that dynamic in any meaningful way. The filmmakers also treat women like nothing more than the loot of success. Easy-E’s “Wet & Wild Pool Party” features dozens of topless, anonymous women, mostly framed from the neck down and thighs up. One troubling scene, which is meant to be amusing but isn’t, features the group humiliating a naked woman by tossing her into a hotel room hallway and locking the door behind her. Scantily clad women always seem to be hanging around in the film, and only, later on, do the artists’ girlfriends and wives receive lines of cursory dialogue.

Of course, as emphasized above, this is an inside affair, with producers Cube and Dre helping to shape the material along with Gray, who directed Cube’s music videos and Friday, the Cube-written stoner comedy from 1995. The material jealously centers on these two men and Easy-E, ignoring contemporaries such as the aforementioned Public Enemy, or the resultant West Coast-East Coast rivalry. Nevertheless, Gray manages to balance the ensemble biopic gracefully and gives each of the three central members their due over a two-and-a-half-hour runtime. O’Shea Jackson, Jr., Jason Mitchell, and Corey Hawkins each deliver strong performances—in particular, the former two, while Hawkins seems somewhat tame and fresh-faced for Dre. The technical presentation is top-notch, especially the slick lensing of Matthew Libatique (a longtime collaborator with Darren Aronofsky and Jon Favreau). And the soundtrack, excellent, is comprised of the original vocal performers with occasional deviations. Overall, the story is epic enough that audiences will experience the significant musical and social influence N.W.A. had on the larger community of hip-hop, and how that influence continues to shape contemporary artists.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review