Southpaw

By Brian Eggert |

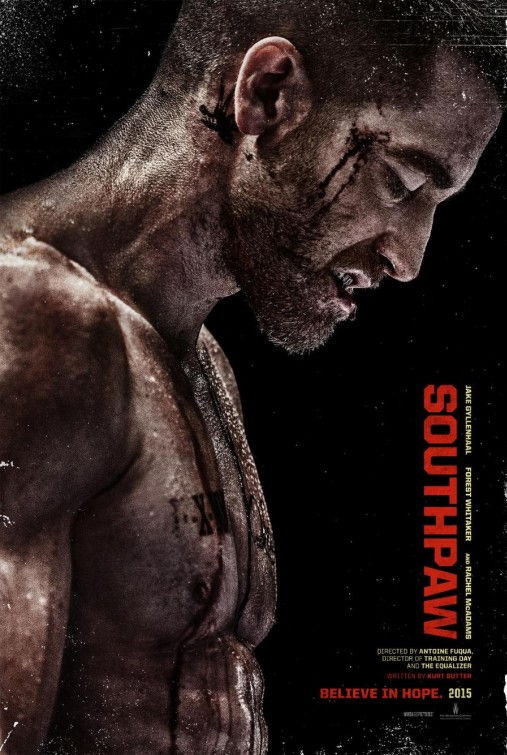

Spattered with blood and sweat, director Antoine Fuqua’s melodrama Southpaw adopts every cliché imaginable from boxing films of the last several decades. By design, the cinematic boxing ring gives way to intense human drama, often centered on a solitary, flawed, and troubled contender who punches his way through whatever issues he’s trying to resolve. Fuqua and screenwriter Kurt Sutter (TV’s The Shield and Sons of Anarchy), both obsessed with various forms of masculine aggression, create such a formula character in Billy “the Great” Hope, impressively rendered in a rage-fuelled portrayal by Jake Gyllenhaal, a performance around which there’s talk of awards consideration. However, the entire film hinges on Gyllenhaal, because everything else onscreen adopts the worn-out blueprints of every boxing film you’ve ever seen.

Boxing films require a strong leading performance. What would Raging Bull be without Robert De Niro or Rocky without Sylvester Stallone in his most iconic role? Fuqua conjures a stirring turn from his leading man and, after last year’s Nightcrawler, Gyllenhaal delivers another body-transforming performance, as Billy comes to life through the actor’s method-style devotion to pristine physicality and occasionally unintelligible mumbling. Gyllenhaal lost 15 pounds for the role and drew his skin as tight to his muscle as humanly possible. The result looks like a sculpture of the human musculature. And while Gyllenhaal’s body remains ever-impressive, the screenplay doesn’t give the actor much to do outside of the norm. Billy is overwhelmed with anger, sadness, and rare fits of joy, and not one emotion registers under eleven.

An undefeated lightweight champion just a few bouts away from being punch-drunk, Billy lives the high life, though he grew up “in the system” in Hell’s Kitchen, alongside his future wife Maureen (Rachel McAdams, very good). Now they have a preteen daughter, Leila (Oona Laurence), and remain thankful for their good fortune. Much to the chagrin of Billy’s scheming, Don King-esque manager (50 Cent), Maureen wants him to quit while he’s ahead, afraid that Billy’s angry, defenseless boxing style will leave him brain-damaged beyond recognition. And Billy agrees, because he loves his wife and child more than anything. But when Maureen is killed during a tragic encounter with one of Billy’s would-be challengers, he loses everything.

Ruined and on the verge of suicide, Billy neglects his daughter and finances, and soon enough, the courts take Leila away, and Billy is left penniless. In order to get Leila back, he must prove to the court he’s a stable father, and so he takes a job cleaning a local gym run by tough-love owner Tick Willis (Forest Whitaker). Having gone from a million-dollar mansion to a crusty apartment, Billy likewise takes an earthy approach to training, courtesy of Tick, who despises professional boxing. Nevertheless, Tick agrees to train Billy in a boxing style designed to control Billy’s senseless rage. He learns strategy and defense. And when, quite predictably, Billy must reenter the ring against the fighter who had a hand in Maureen’s death, he’s a new fighter altogether. With Leila sitting in the dressing room, watching her father fight the guy who prompted her mother’s death, Southpaw comes to an unsurprising climax.

The fight scenes, though visceral, have been over-cut by editor John Refoua, and cinematographer Mauro Fiore seems to have no rhyme or reason to his varied angles and camera placement, except maybe a desperate and ineffective attempt to make the audience feel like we’re inside the ring with Billy. There are also at least two training montages, one ridiculously set to rapper Eminem’s “Phenomenal”, where six weeks of exercise and instructions are glossed over in about 60 seconds of screentime. But training montages come with the territory, as do announcer commentaries during the final bout. These announcers seem to have read the script and highlighted the main plot points, then they proceed to remind the audience of the stakes, annoyingly suggesting Billy is out for “revenge”. It’s yet another example of how Fuqua overemphasizes everything onscreen, as opposed to letting the drama in the ring speak for itself.

Indeed, though his performance is larger-than-life and often quite good, Gyllenhaal cannot be blamed for the overcooked quality throughout Southpaw, whose title refers to the unorthodox stance Tick teaches Billy. Fuqua is notorious for going over the top. In his terrorists-attack-the-White-House yarn Olympus Has Fallen, Gerard Butler threatens the top baddie that he’s going to stab him in the brain, and then he does. In Fuqua’s adaptation The Equalizer, Denzel Washington uses everything from hammers to power drills to dispose of mobsters. Fuqua has no time or inclination for subtlety or restrained emotions, so exploring the boxing subgenre seems like a natural choice for him. Unfortunately, Fuqua has resolved to repackage familiar tropes into the kind of manipulative, transparent filmmaking audiences have come to expect from this director, except without anything except Gyllenhaal’s fine performance to distract us from how humdrum it all seems.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review