Silent House

By Brian Eggert |

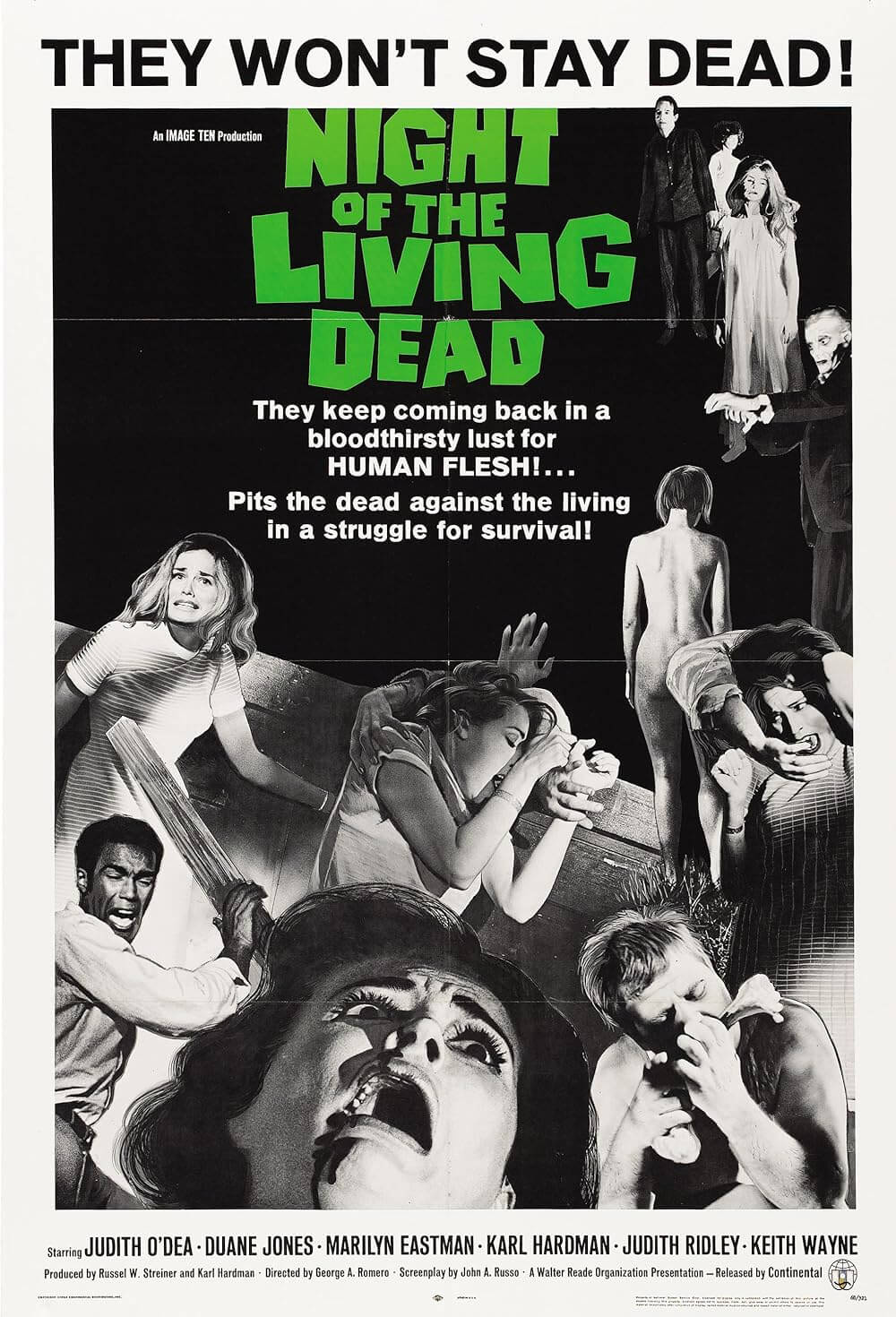

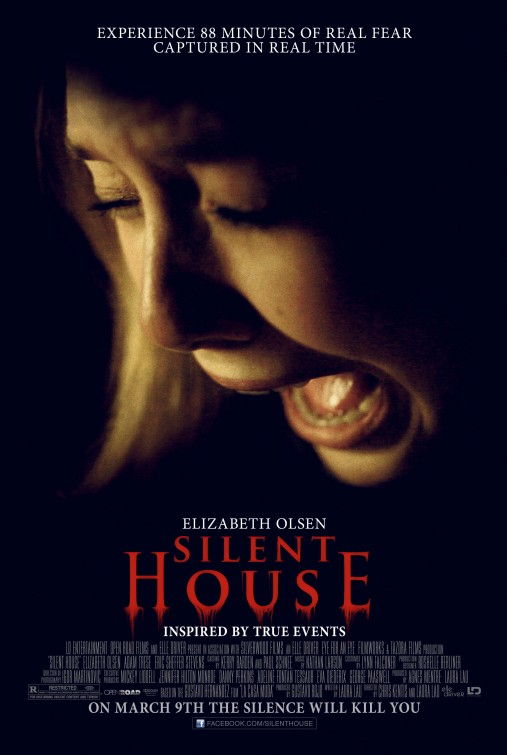

Chris Kentis and Laura Lau, makers of that pointless lost-at-sea tale Open Water, engage another hollow odyssey with Silent House, a horror movie that’s serviceably scary at first, shot with increasingly annoying shaky camerawork, and leads to a twist that’s enough to elicit catcalls from the audience. Elizabeth Olsen plays Sarah, who, along with her dad John (Adam Trese) and uncle Peter (Eric Sheffer Stevens), sets out to refurbish her family’s dilapidated old lakehouse that’s been abandoned for a year. The windows are boarded, and the power is out, leaving the inside black as pitch. All at once, Sarah finds her dad nearly dead as she’s chased inside the inescapable house by what’s presumably a band of squatters who’ve moved in. Weeping and terrified throughout, she investigates noises in the dark only to find countless false scares, and she annoyingly ventures to explore the dank, dripping basement. Those clichés are minor next to the one that comes at the end.

Based on La Casa Muda, the 2010 Uruguayan shocker by Gustavo Hernández, the movie’s events were supposedly based on a true story. And if you believe that one, I’ll tell you another. It’s sold under the pretense that we will experience the events onscreen as they occur in “real-time,” as the producers have claimed that the entire production was completed in one unbroken take. Riiight. Igor Martinovic’s obnoxiously shaky, sometimes out of focus, extreme close-up camerawork—the sort of visual flourishes normally home in a “found footage” movie, which this is not—fades to black or twitches in unintelligible motions in which a cut could and no doubt is disguised. Moreover, those who saw the film at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival have noted that everything after the eye-rollingly stupid twist was reshot, so how can the movie be one unbroken shot? Also, if the producers consider the lame twist in the wide release better, I’d hate to think about how it originally ended.

Fortunately, the movie has Olsen, who appeared in last year’s lauded Martha Marcy May Marlene; she manages to display some genuine acting chops and keep the audience involved in spite of the silly plotting and irritatingly unstable execution. Sarah’s forced into several situations where she must keep silent less her pursuers find her, and Olsen’s expressions of fear and utter terror without screaming are effective. (Then again, Olsen does plenty of screaming, too, enough to make the title nonsensical.) Not so with costars Trese and Stevens, whose respective father and uncle both make hapless shifty eyes about some Polaroids left out, making a point to hide them from Sarah. Oh, never mind these, they’re nothing, they say. Which, of course, means they’re very important. We’re meant to overlook such details during the frenzied situation, but they’re so obviously pointed out to us that we can’t help but dwell.

When we finally discover what’s actually going on, Lau’s script turns into a disturbing if sloppily played psychological thriller with symbolism abound. Early on, someone makes an offhand remark about the holes in Sarah’s head, which we learn later reflects mold-ridden holes in the house, making for an obvious metaphor. By the time walls start to bleed, and characters appear in impossible places, the surreality of what we see leads to one of the most overused, clichéd devices in movie history. Though I’ve alluded to it plenty, I’ll avoid coming right out and saying it. But when it was revealed, some moviegoers in my screening laughed while others just got up and left. One exclaimed, “Are you kidding me?” I envied those who left.

Still, there’s something to be said for Silent House’s choreography, and Martinovic’s skill at following Olsen up and down staircases, in various rooms, outside and back again, and cleverly making it look like one virtuoso shot. Other flourishes aren’t so successful, such as when Sarah uses a Polaroid camera’s flash to illuminate the darkened house; inevitably, we see movement in the brief flash, but this trick is all too familiar not to expect what’s coming. For what feels like a very long 85-minute runtime, we’re right there with Olsen, tolerating genre clichés that can’t be made up for with flashy editing or a good performance. Shoddy attempts at character development, references to Facebook, and that unforgivable ending sour the experience further, making it almost intolerable.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review