The Definitives

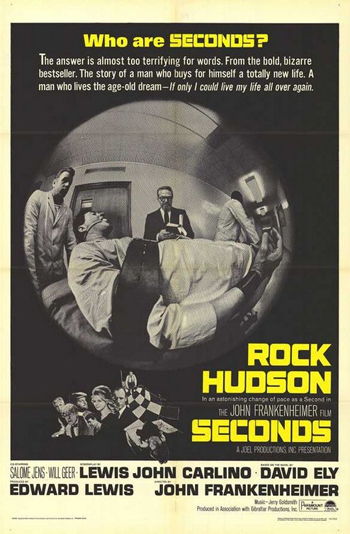

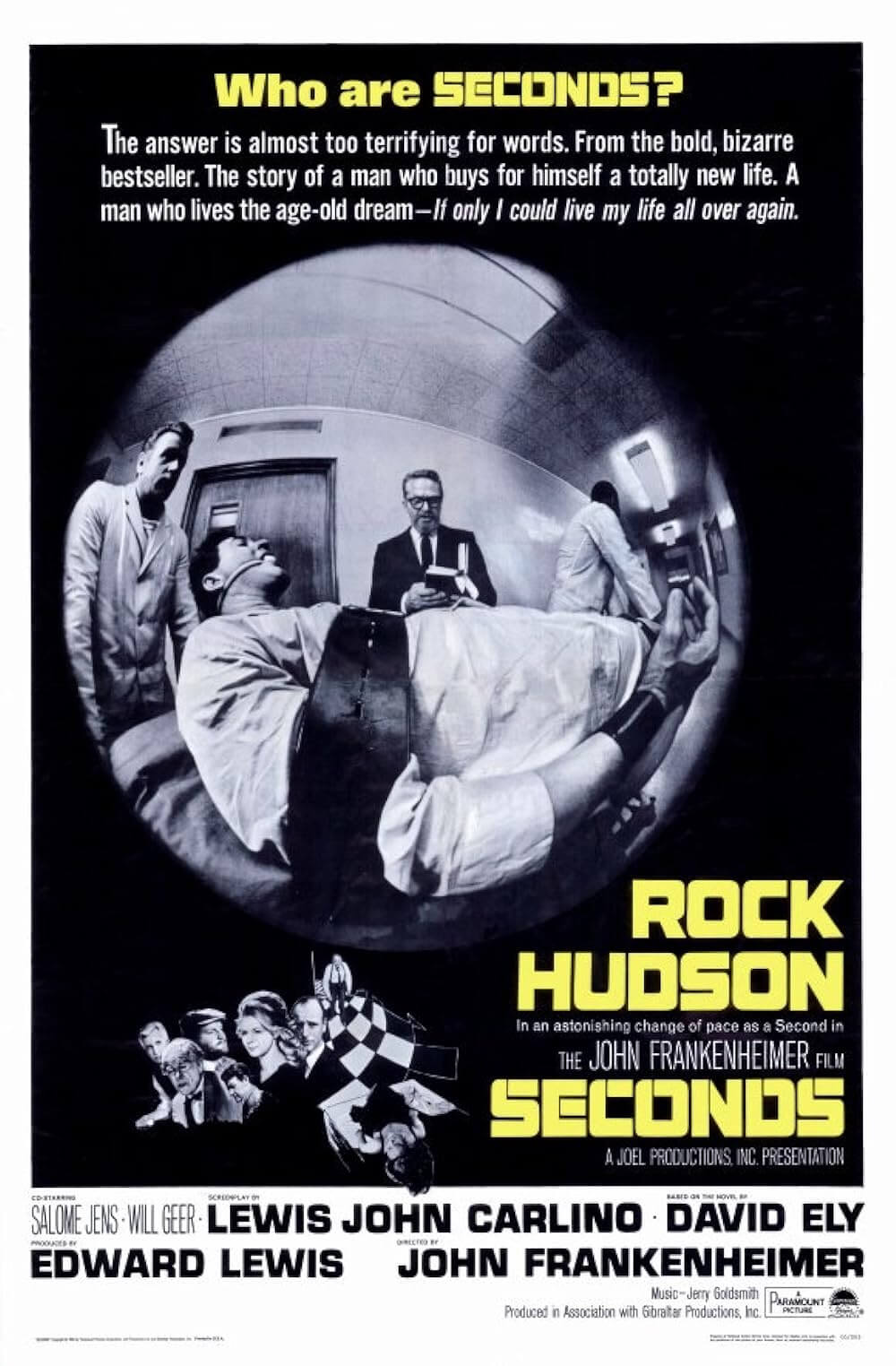

Seconds

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Arthur Hamilton has everything he’s been told he should want. A successful gray flannel suit banker, he owns a nice house in Scarsdale, a comfortable New York suburb. His loving wife has given him a now grown daughter, who herself has married well, to a doctor. He lives the American Dream, and surely those with less envy his life. Nevertheless, Arthur is bored, internalized, and restless in a midlife crisis. A second chance presents itself when his old friend Charlie, someone he thought was long dead, approaches him with a proposition: For a considerable sum of money, Arthur can have a different life and start afresh with a new face and identity. “All new, all different, the way you always wanted it,” a salesman tells him. Pressured, if not blackmailed into a Faustian pact with a surreptitious, unnamed company, Arthur gives up his former life and, following a transformative plastic surgery and months of conditioning, receives a new persona as “Tony Wilson”. Now with the face of a younger and more handsome Wilson, he’s relocated to a California house overlooking the Pacific and given a new career as a professional artist, the Company carefully monitoring his acclimation. But even with a new face and métier, the doldrums of his ordinary existence have drained the former Arthur Hamilton of his ability to experience happiness to almost hedonistic extremes. Faced with his discomfited self, he slowly uncovers the nightmarish ways in which those who engineered his new life now control it.

Cynical and emotionally dystopian, John Frankenheimer’s Seconds was released in 1966 to almost unanimous aversion. While other filmmakers explored the freedoms associated with the 1960s, Frankenheimer released a film in which the aftereffects of McCarthyism were still apparent, and the American Dream was a lie. Despite the draw of popular Hollywood star Rock Hudson appearing as Arthur Hamilton’s “reborn” self Tony Wilson, the subject matter isolated and even attacked its audience, leaving the film unappreciated for decades. Based on the bestselling 1963 novel by David Ely, the picture considers the horrific outcome of one common man’s desire to live his life over again, and in the process shows an incredible disdain for the common fantasy to escape ordinary, stifling working class mores. Underneath the surface of Seconds reside several parallels between the lives of its actors and the film’s central theme of denying one’s identity, not only with Rock Hudson’s depiction of Wilson as it relates to Hudson’s sexuality, but also with the elder Hamilton, played by the blacklisted John Randolph. The most fascinating throughline in the picture, however, is its raw contempt for self-negation through assigned lifestyles, be they bourgeois or bohemian. Frankenheimer’s film suggests a person’s contentment lies within, that you cannot adopt a lifestyle to find happiness, just as you can’t start over by rubbing out your history. A person is nothing if not an accumulation of time and memory; without them, we are shells, fractured and incomplete.

Although the casting of Randolph as Hamilton and Hudson as Hamilton’s new identity Wilson suggests a diptych structure to Seconds, this is an illusion, and seeing beyond the actors is key to perceiving the film’s thematic power. The narrative’s protagonist remains the same throughout, as we see when the same languid quality that filled Hamilton’s life soon fills Wilson’s. Hudson’s performance is astonishing; he adopts Randolph’s inner emptiness in his gestures and expressions to make the transition between actors seamless. Though Hamilton has everything he wanted in his new body and life, he drinks more and lies awake in bed, staring at the ceiling. He tries to paint but cannot. Like Frankenstein’s monster, he’s a curiosity—an abomination from a radical surgery left to feel isolated from everyone around him. He resigns himself to long, searching walks on the beach. There he meets Nora (Salome Jens), a divorcée who helps him feel alive by taking him to an orgiastic bacchanalia wine festival where, for a short time, he’s able to shed a part of his former self. He and Nora promptly fall in love until he realizes she’s been planted by the Company to help him adjust to his new identity. In fact, all of his new friends are “reborns” like himself, none of them genuine. Fleeing California, he returns to New York to see his former wife (Frances Reid) and poses as one of Hamilton’s friends. He asks her about her marriage to Arthur Hamilton, and she explains their marriage had failed because Hamilton so vigorously pursued things he was told he should want, but he never really understood what he wanted.

Although the casting of Randolph as Hamilton and Hudson as Hamilton’s new identity Wilson suggests a diptych structure to Seconds, this is an illusion, and seeing beyond the actors is key to perceiving the film’s thematic power. The narrative’s protagonist remains the same throughout, as we see when the same languid quality that filled Hamilton’s life soon fills Wilson’s. Hudson’s performance is astonishing; he adopts Randolph’s inner emptiness in his gestures and expressions to make the transition between actors seamless. Though Hamilton has everything he wanted in his new body and life, he drinks more and lies awake in bed, staring at the ceiling. He tries to paint but cannot. Like Frankenstein’s monster, he’s a curiosity—an abomination from a radical surgery left to feel isolated from everyone around him. He resigns himself to long, searching walks on the beach. There he meets Nora (Salome Jens), a divorcée who helps him feel alive by taking him to an orgiastic bacchanalia wine festival where, for a short time, he’s able to shed a part of his former self. He and Nora promptly fall in love until he realizes she’s been planted by the Company to help him adjust to his new identity. In fact, all of his new friends are “reborns” like himself, none of them genuine. Fleeing California, he returns to New York to see his former wife (Frances Reid) and poses as one of Hamilton’s friends. He asks her about her marriage to Arthur Hamilton, and she explains their marriage had failed because Hamilton so vigorously pursued things he was told he should want, but he never really understood what he wanted.

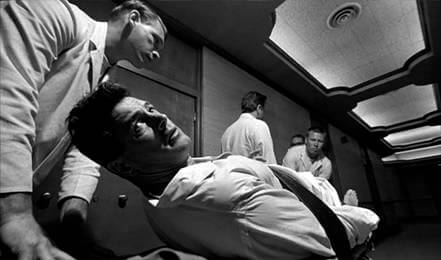

Determined to start over once more, he returns to the Company and asks for yet another identity. While there, he meets up with Charlie (Murray Hamilton), to whom he bewails “The years I’ve spent trying to get all the things I was told were very important, that I was supposed to want. Things! Not people or meaning. Just things.” This time, he thinks, it will be different. Charlie, too, admits he has grown dissatisfied with his new identity; however, the Company’s policy on acquiring thirds demanded Charlie recruit a new client—and he recruited Hamilton. In turn, Mr. Ruby (Jeff Corey), the executive who finally convinced Hamilton to participate, and the Old Man (Will Geer), the Company’s founder and the film’s resident Mephistopheles, explain that Hamilton must recruit someone else into the program if he wants a new identity. But rather than consign someone else to the suffering he’s endured, Hamilton decides to act unselfishly and refuses to submit anyone else, having realized his dissatisfaction derived from his lifelong pattern of allowing others to tell him what’s important. All at once, the Company prepares him for another surgery. As Hamilton is tied down to a gurney, he’s wheeled to an operating room and a priest follows, reading him his last rites. The nightmare is complete. The Company’s policy is to send uncooperative clients like Hamilton to the Cadaver Procurement Section, where the subject is killed and their body used to fake the death for a new client.

Born in 1930, John Frankenheimer began making films in 1951 for the United States Air Force and went on to become one of the most radical filmmakers of the 1960s. After growing up in a prosperous family in New York City during the Great Depression, he graduated as valedictorian from his high school military academy and later earned a bachelors degree in English. To avoid the Korean War draft, he joined his school’s ROTC program and volunteered for the Motion Picture Squadron to make short subject documentaries and informational pieces. In time, his experience behind the camera led to a lucrative career in the early years of television, where he directed well over 150 shows, teleplays, commercials, and TV movies before making his first feature length film, The Young Stranger, in 1957.

After his rise to Hollywood, Frankenheimer reached his peak in the Sixties through motion pictures that struck the era’s very core with their themes of paranoia, humanism, liberalism, and dynamic technical craftsmanship. A string of highly acclaimed and artistically celebrated films such as All Fall Down (1962), Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Seven Days in May (1964), The Train (1965), and Grand Prix (1966) were followed by two decades of commercial failures and the director’s own fight with alcoholism. Not until the 1990s with a series of four Emmy-winning TV movies (Against the Wall and The Burning Season (1994), Andersonville (1996), and George Wallace (1997)) did Frankenheimer make a comeback in Hollywood, eventually releasing the celebrated spy-actioner Ronin (1998) to enthusiastic praise before his death in 2002.

Seconds is pure Frankenheimer, untamed by the filmmaker’s potent desire to frighten his audience out of their social apathy. It’s a film made out of passion, not commercialism, and because of its disastrous performance at the American box-office, it forced the director to make a series of commercial-minded decisions, leading to less creative films and his long, mid-career lull. Doused in the same paranoia that drove his two pictures The Manchurian Candidate and Seven Days in May, Seconds completes what is sometimes called his “Paranoia Trilogy”. The film was made by Frankenheimer for Joel Productions, a company owned by Kirk Douglas, who, after securing the rights, opted not to star. Frankenheimer coproduced it along with Edward Lewis, his collaborator on Seven Days in May, and enjoyed a great amount of freedom of control over its development. In addition to assisting screenwriter Lewis Carlino with the adaptation, Frankenheimer worked closely with art director Ted Haworth and his cinematographer James Wong Howe (The Thin Man, Sweet Smell of Success) on the look of the film.

Visually, the look of Seconds is unforgettable, from Howe’s disorienting camerawork to Saul Bass’ opening titles where human facial features are stretched and contorted into one another. The renowned Howe was nominated for an Oscar, his eighth, for his black-and-white photography on Seconds, which demonstrates a filmmaker allowing his cinematographer incredible freedom of invention. Already a master of high contrasts and deep focus, Howe incorporates fisheye lenses, body-mounted cameras, and handheld techniques in Seconds to give the picture an off-kilter worldview. Howe and Frankenheimer make the picture feel like a documentary recorded in someone’s nightmare. For the surgery scenes, Howe shot an actual rhinoplasty and the director was forced to operate a second camera for a squeamish cameraman. Frankenheimer’s own compositions were enhanced by Howe’s fondness for unique angles and lighting. Scenes where Frankenheimer places an immobile character close in the foreground, while others in the far backdrop are enhanced by Howe’s dramatic wide-angle lensing, as is the film’s visual theme of fragmented images. Again and again we see Hamilton looking in the mirror after his surgery, the reflection bouncing from one mirror image to another to represent the character’s disjointed identity.

Frankenheimer may have had creative freedom, but the financiers at Paramount insisted on a bankable star. Originally, the director wanted Laurence Olivier to play both Hamilton and Wilson, but the studio believed the British thespian would not attract the appropriate crowds. Marlon Brando turned down the role(s), but Rock Hudson agreed, and even suggested that Frankenheimer find a second actor to play the elder Hamilton. Blacklisted actor John Randolph was cast and would star as Hamilton in the first forty minutes of the picture; Hudson would finally appear halfway through as Wilson. Enthusiastic about his finished film, Frankenheimer persuaded Paramount to screen it at the Cannes Film Festival in 1966, where it was greeted with such acidity from the customarily impassioned Cannes critics that the director refused to attend the festival’s subsequent press events. Frankenheimer was devastated. For its stateside release, Paramount, reeling from the poor reception at Cannes, abbreviated the original cut to lessen the liberated display of sexuality in the bacchanalia sequence; the studio also barely marketed the picture, and it ultimately failed to draw audiences or impress critics of the time, flopping miserably. As a result, Frankenheimer reassessed how he would select his future projects and became perhaps overly conscious of a film’s commercial appeal. Although his new approach led to the commercial triumph Grand Prix, it also led to creative duds such as French Connection II (1975) and Prophecy (1979). Today, Seconds has developed a following and become something of a cult masterpiece. Frankenheimer himself noted how the film “went from failure to classic without ever being a success”.

In a turn of tragic irony, Frankenheimer pursued his financially successful career in filmmaking by resisting the kind of projects, like Seconds, that inspired him most. Here, he set out to produce a “horrifying portrait of big business”, just as he had critiqued other major institutions with his previous films: McCarthy-era politics in The Manchurian Candidate and the U.S. government and military’s Cold War extremism in Seven Days in May. In Seconds, t he Company, headed by Geer’s Old Man, began with the best intentions. “I wasn’t aiming to make a lot of money,” the Old Man remarks soothingly. “I was waging a battle against human misery.” But as he continues to explain to Wilson, who’s about to be tied down and prepared for termination, the Company’s survival and profits took precedence over his customers’ desire for a second chance at life. Worse still, the sheer quantity of reborns unable to acclimatize to their new identities meant the Company could save on sales force costs and use them when they returned, employing them to convince others to join the program. If that failed, there was always the need for raw materials in Cadaver Procurement. The cold logic of the Old Man and his company reflects not only the capitalistic momentum of American commerce but also, sadly, the artistic pathway of Frankenheimer’s career and his willingness to sacrifice his certain artistic ideals just to keep working, no matter the project.

For Rock Hudson, Seconds must have had personal significance beyond housing what he later called one of his own favorite performances. Born Roy Harold Scherer, Jr., the famously homosexual actor adopted his stage name for Hollywood and later agreed to a false marriage to conceal his sexuality, all part of a persona manufactured by his agent Henry Wilson. After getting noticed in the Anthony Mann Westerns Winchester ‘73 (1950) and Bend of the River (1952), Hudson starred in a series of fantastic Douglas Sirk melodramas (including Written on the Wind, 1956) and earned an Oscar nomination for George Stevens’ Giant (1955), though his biggest successes were three romantic comedies alongside Doris Day. Having been voted Hollywood’s most popular actor by American moviegoers in the Fifties, by 1966 Hudson’s career was nonetheless on the downswing. Now he actively sought the lead role in Seconds, although afterward, he confessed that he knew he wouldn’t be able to supply performances for both Arthur Hamilton and Tony Wilson. To get the part, he even agreed to a screen test (something proven actors rarely do) for the uncertain Frankenheimer, and to keep it he convinced the director to split the part for two actors. Further dedicating himself to the role, Hudson played a scene actually drunk and remained that way for the 3 days it took to film the party sequence at Wilson’s California home.

For Rock Hudson, Seconds must have had personal significance beyond housing what he later called one of his own favorite performances. Born Roy Harold Scherer, Jr., the famously homosexual actor adopted his stage name for Hollywood and later agreed to a false marriage to conceal his sexuality, all part of a persona manufactured by his agent Henry Wilson. After getting noticed in the Anthony Mann Westerns Winchester ‘73 (1950) and Bend of the River (1952), Hudson starred in a series of fantastic Douglas Sirk melodramas (including Written on the Wind, 1956) and earned an Oscar nomination for George Stevens’ Giant (1955), though his biggest successes were three romantic comedies alongside Doris Day. Having been voted Hollywood’s most popular actor by American moviegoers in the Fifties, by 1966 Hudson’s career was nonetheless on the downswing. Now he actively sought the lead role in Seconds, although afterward, he confessed that he knew he wouldn’t be able to supply performances for both Arthur Hamilton and Tony Wilson. To get the part, he even agreed to a screen test (something proven actors rarely do) for the uncertain Frankenheimer, and to keep it he convinced the director to split the part for two actors. Further dedicating himself to the role, Hudson played a scene actually drunk and remained that way for the 3 days it took to film the party sequence at Wilson’s California home.

Repressed sexuality is a major undercurrent in Seconds, signaling the sexual revolution movement among middle-class Americans in the 1960s. And so it’s easy to see why Hudson, whose double life was a constant throughout his career despite its widespread knowledge throughout the industry, was drawn to a picture about the manipulation of appearances and the denial of one’s inner self. Before Hamilton opts into the program, there’s a bedroom scene where his wife makes her way onto her husband’s separate bed. She offers herself up to him, but he remains cold and unwilling, the moment as unsexy a depiction of middle-aged sexuality as ever to appear in cinema. Later, after his transformation into Wilson, Hamilton attends the bacchanalia festival with Nora and finds himself uncomfortable in his surroundings. Free spirits disrobe to their nethers and gaily dance about, the frantic cutting of the sequence reflecting Hamilton’s discomfort with his own desire to join them. He stands on the margins, watching, enticed and ashamed for it, until Nora strips and leaps into a grape crushing vat along with countless nude others. Finally the crowd gathers him and, though he protests, forces off his clothes; he’s plunged into the vat and covered in grape must. Clinging to Nora, he at last lets go and begins to shout with ecstasy and joy. Hamilton’s sexual repression seems cured, a hopeful idea for Hudson, whose secret could not be so easily or publically freed from its constraints at the time.

Whether or not Frankenheimer was aware of the offscreen parallel for Hudson remains uncertain, although he was no doubt sensitive to the parallels inherent to John Randolph’s casting, as well as those related to Will Geer, Jeff Corey, and a walk-on role held by Ned Young, the screenwriter of Frankenheimer’s The Train. Randolph and the others mentioned had all been blacklisted in the previous decade when they were called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and refused to name any known Communists in Hollywood. Although McCarthyism had subsided since then, Randolph had not yet been accepted back into the fold; Seconds would be his first screen role since his blacklisting. By including these blacklisted actors in the film, Frankenheimer constructs a metaphor for Hamilton’s refusal to recruit someone else for the Company, demonstrating how those unwilling to cooperate with HUAC were punished by being blacklisted and, in some cases, forced to take on new identities during their exile. In the case of blacklisted director Jules Dassin (Brute Force), he went to France while banished and made foreign-language films like Rififi (1955). Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, the blacklisted screenwriters of The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), were forced to sign screen credit over to non-English speaking French author Pierre Boulle. To further emphasize the symbolism, Howe’s camerawork suggests the film’s characters are being watched and the technique echoes the paranoia of communist witch hunts of the Fifties.

Regardless of these rather subversive subtextual themes, the metaphors present in Seconds never overflow into outright political commentary, leaving the film to absorb the viewer into its compelling, frightening human drama. Temped by the Company’s promised escape from himself, Hamilton joins the program and the story plays out like, as often observed, an episode of The Twilight Zone. As if conceived by Rod Serling himself, the film follows the show’s familiar structure where everyday characters enter a Kafkaesque world in which nothing is as it seems, all leading to a terrifying twist where reality is turned upside-down. Seconds has far more complex motivations and substance propelling it, but the comparison is appropriate. In many ways, it reformats a similar dramatic strain from The Manchurian Candidate by proposing that the central character’s psychological dilemma is resolved only through an embrace of his memories. Frank Sinatra’s brainwashed American soldier must make sense of the fragmented images in his head by remembering what happened to him in Korea, whereas Arthur Hamilton must finally accept his choices and realize that he cannot relive his past. Frankenheimer even cast The Manchurian Candidate’s brainwasher (played by Khigh Dhiegh) as the Company’s resident psychiatrist in Seconds, emphasizing a parallel between enforced conditioning and the pursuit of happiness as defined by the American Dream. Whether you deny yourself by force or by force of will, the result is the same. Frankenheimer commented, “You are the result of your experiences, the result of your past… If you take away your past, you don’t exist as a person.”

With Seconds, Frankenheimer created a deceptively downbeat identity crisis, where the final shocking moment of Arthur Hamilton’s death arrives in an atmosphere of paranoia, the imagery lurid and dreamlike, Hudson’s panicked realization of his character’s fate so extraordinarily unsettling. The post-World War II American Dream to build a family, home, and career prove to be often unsatisfying illusions conceived by society, just as the charms of bohemia are temporary, and when Hamilton realizes how meaningless such assigned desires are, the Company can no longer control him and therefore cannot use him, alive. Although Hamilton’s cruel fate is horrific, in his epiphany he transforms, albeit just for the few moments of his life that remain to him, with his refusal to accept an assigned material existence, and his desire to find himself and pursue some kind of genuine happiness. If Seconds contains a message, it’s a subversive and admirable one that rejects escapism and conformity in all their forms, and further delineates a failure on the part of the individual to recognize what he wants and how to achieve it, or accept personal responsibility when he fails. Perhaps the director’s most personal film, Seconds holds a deeply human message and marvelous cautionary tale, ever hopeful to viewers who heed its warning.

Bibliography:

Armstrong, Stephen B. Pictures About Extremes: The Films of John Frankenheimer. London: McFarland & Company, Inc: 2008.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review