The Definitives

PlayTime

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In the 1960s, French president Charles de Gaulle made a vow to develop his country’s economy and reform Paris into a modern city. Knocking down older houses in urban Right Bank districts, developers rebuilt parts of the city and its suburbs and put up modernized blocks of glass and steel in their place. High-rise structures were allowed within Paris for the first time, and their anonymous façades soured the City of Lights’ historical atmosphere and represented an unsightly contrast to her famous monuments. The city of the future was on its way, and its expansion was modeled according to dull, functional, pointedly Americanized specifications. During this time, filmmaker Jacques Tati, who had grown up in the earthy quarters of Paris and lived there most of his life, decided to make a film about the ache of losing his old Paris to a more contemporary cityscape. To accomplish this, Tati conceived a most ingenious and maniacal idea: he would build a city of his own design, on which he could shoot freely and have absolute control. His crew called it Tativille. And while his eventual film, named PlayTime, would become Tati’s most ambitious and impressive motion picture of his career, it was not merely a satire or comic censure of the modern metropolis. Through the film, his appreciation for the imposing splendor of such architecture and its absolute size and beauty would become evident, just as his audience feels at once lost and rapt in a sense of wonderment at his production’s sheer scope and artistic genius.

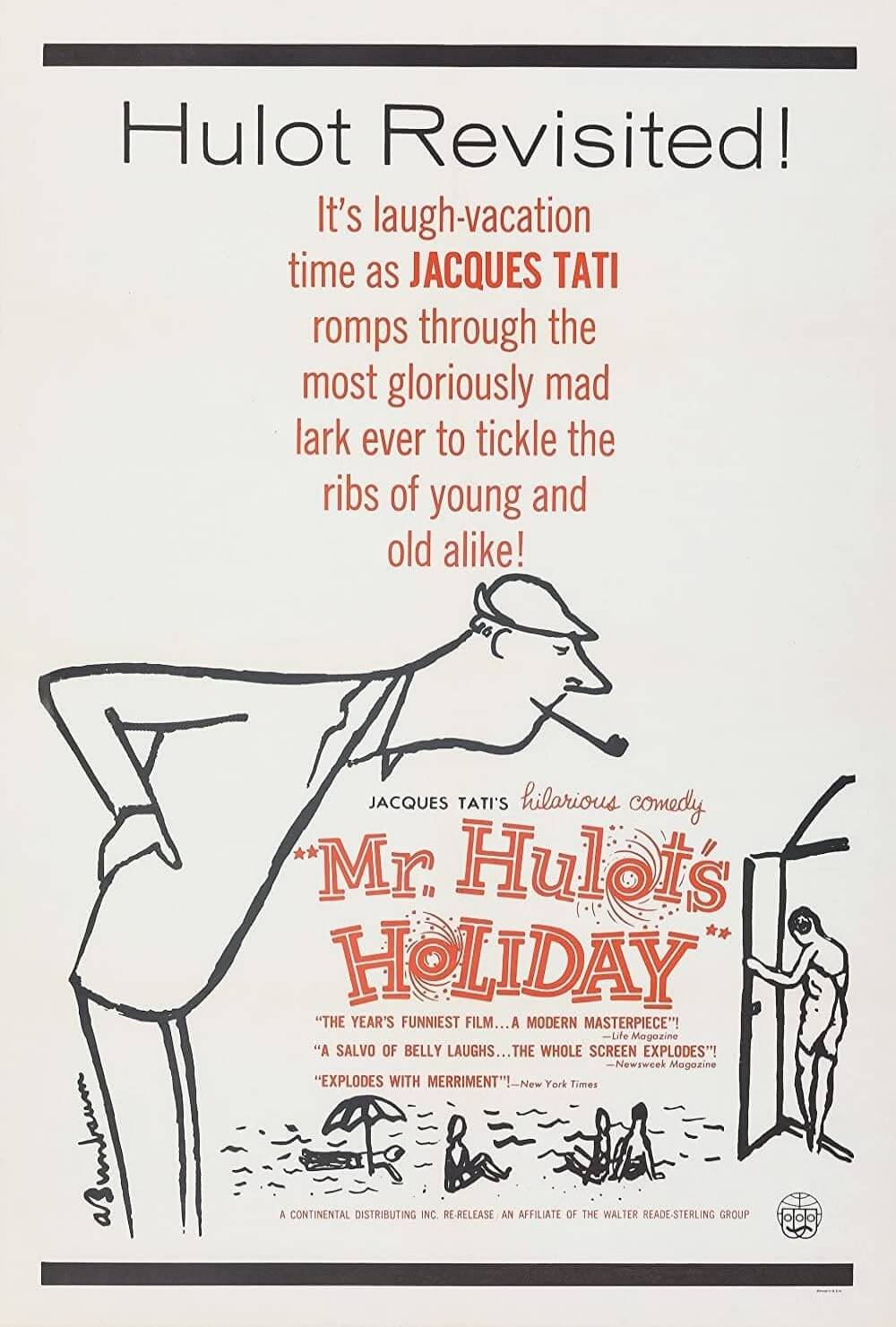

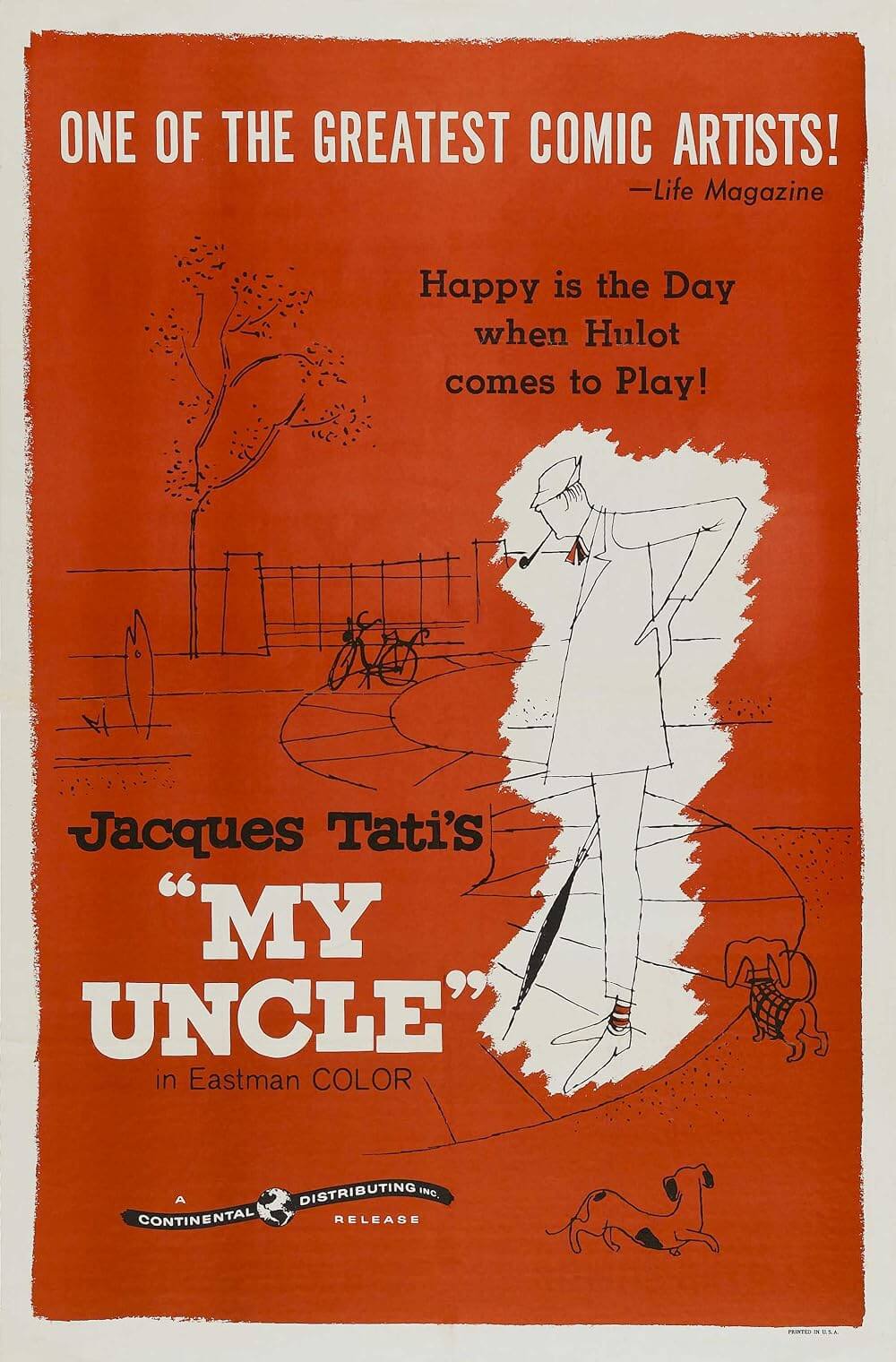

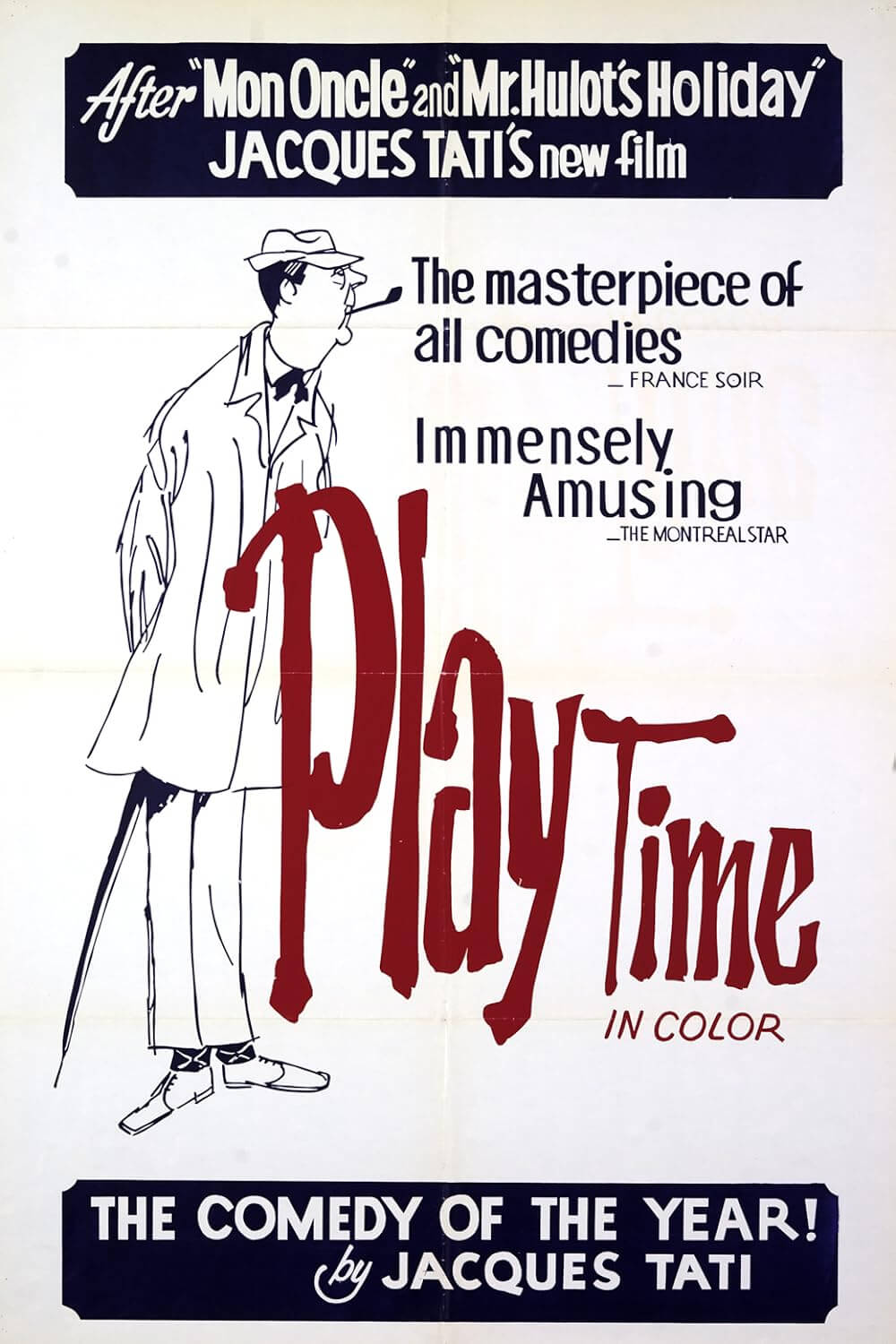

Upon its release in 1967, PlayTime was the most expensive film ever made in France. And yet, it contains almost no story and its dialogue is mostly inconsequential. Like Tati’s other pictures, the dialogue has been post-synchronized and its volume turned down to direct our attention to forms of behavior and visual gags in the impractical spaces he’s chosen to depict. Fore, middle, and backgrounds are all in crisp focus and ready for our eyes to explore, occupied at times by, among a whole population of others, Tati’s famous alter ego Monsieur Hulot, who first appeared in M. Hulot’s Holiday (1953) and then Mon oncle (1958). With his long-stemmed pipe, raincoat and hat, and his pants often too short, Hulot moves about somewhat lost outside of his “old quarter” of Paris, bemused and confounded by urbanization and modern gadgetry. An iconic figure as connected to Tati as the Little Tramp was to Charles Chaplin, Hulot also represented an artistic hindrance for Tati, who by the early sixties wanted to move beyond his beloved character and explore whole environments more than a Hulot-centric narrative and gags. Nevertheless, without Hulot’s popularity, any commercial prospects for PlayTime would have been nonexistent, and so Hulot, although present in the film, has a minimal role. Like all characters and spaces within the frame, Hulot becomes part of the scenery; he disappears for long patches of screentime, seemingly lost in the bustle of the modernized world. But then, this seems to be Tati’s purpose for the picture, for his audience to observe the world we live in and find the simultaneous beauty, humor, and sad sort of absurdity in what we’ve built and keep building upon.

When Tati first embarked on the production, his fourth picture was originally titled Récréation, as in leisure or amusement, and much like his unified critique and embrace of the modern getaway in M. Hulot’s Holiday or modern living spaces in Mon oncle, Tati sought to transform metropolitan Paris into a source of irrationality and playful recreation. For his new project, he set out to micrify M. Hulot amid a stifling cityscape of modern airport corridors, mazelike cubicles, tradeshows boasting the latest conveniences, confined living spaces, and busy restaurants—all of steel and glass and in varied shades of gray. Hulot was more of an obligatory figure in this setting, intentionally lost amid the cityscape’s active population to allow the director to orchestrate the wide range of activity in a public space. His enormous presentation would be shot in high-resolution 70mm, allowing the expansive real-world exteriors to dominate the frame. Just as Hulot was lost in the Hôtel de la Plage resort in M. Hulot’s Holiday and the modernized suburbs in Mon oncle that contrast his home in the earthy “old quarter” neighborhoods of Saint-Maur, he would be an almost insignificant detail on the Tativille set, captured in a larger-than-life frame. Tati remarked “PlayTime is the big leap, the big screen. I’m putting myself on the line. Either it comes off, or it doesn’t. There’s no safety net.” Tati’s previous films were shot on actual locations, however. For PlayTime, surely Tati couldn’t afford what it would cost to take over whole segments of a real-life city or airport, and no city or airport would shut itself down and submit to Tati’s obsessive and exacting directorial style, wherein every detail was observed and labored-over to meticulous effect.

When Tati first embarked on the production, his fourth picture was originally titled Récréation, as in leisure or amusement, and much like his unified critique and embrace of the modern getaway in M. Hulot’s Holiday or modern living spaces in Mon oncle, Tati sought to transform metropolitan Paris into a source of irrationality and playful recreation. For his new project, he set out to micrify M. Hulot amid a stifling cityscape of modern airport corridors, mazelike cubicles, tradeshows boasting the latest conveniences, confined living spaces, and busy restaurants—all of steel and glass and in varied shades of gray. Hulot was more of an obligatory figure in this setting, intentionally lost amid the cityscape’s active population to allow the director to orchestrate the wide range of activity in a public space. His enormous presentation would be shot in high-resolution 70mm, allowing the expansive real-world exteriors to dominate the frame. Just as Hulot was lost in the Hôtel de la Plage resort in M. Hulot’s Holiday and the modernized suburbs in Mon oncle that contrast his home in the earthy “old quarter” neighborhoods of Saint-Maur, he would be an almost insignificant detail on the Tativille set, captured in a larger-than-life frame. Tati remarked “PlayTime is the big leap, the big screen. I’m putting myself on the line. Either it comes off, or it doesn’t. There’s no safety net.” Tati’s previous films were shot on actual locations, however. For PlayTime, surely Tati couldn’t afford what it would cost to take over whole segments of a real-life city or airport, and no city or airport would shut itself down and submit to Tati’s obsessive and exacting directorial style, wherein every detail was observed and labored-over to meticulous effect.

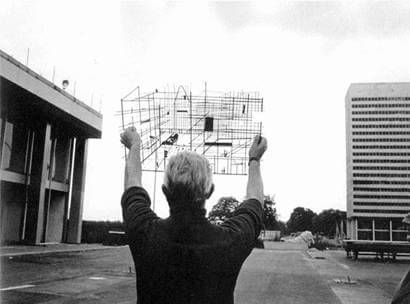

Though his cameraman Jean Badal had proposed that Tati erect a building for the production and then sell it afterward, Tati had something more blindly idealistic in mind. His newly developed company Specta-Films would create massive buildings and offices, roads and streetlights, and even an airport. But rather than make these structures functional spaces that could be resold afterward, Tati intended its use for the French film industry. His studio-set, famously dubbed “Tativille” by the crew, would be build on the southeast corner of Paris, on a wasteland at Saint-Maurice. Construction began in September 1964 and met with almost immediate delays and budgetary problems, and would not be finished until March 1965. Shooting began in April 1965 with a planned 178-day shoot, but lasted until October 1966. During the astonishingly protracted 365 days of actual shooting, minus vacations and stoppages, filming halted sometimes for weeks or months at a time for any number of reasons: bad weather, non-prime lighting conditions, or more commonly because Tati’s money had run out. Tati borrowed funds from government financiers, banks, against Specta-Films’ assets, and eventually his personal fortune. Soon he turned to friends and family. Public figures and admirers contributed too, but it wasn’t enough. In the end, Tati even signed away the rights to his three previous pictures. The final budget for PlayTime was reportedly anywhere between five and twelve million francs; though many bills went unpaid by the time production had wrapped. Famously, Tati quipped that for the cost of building Tativille he could have hired Sophia Loren or Elizabeth Taylor to star in his film.

As mentioned above, no real story exists in PlayTime. The events take place over a 24-hour period, a single day and evening, followed by a brief coda the next morning. A group of American tourists arrive in the Paris airport as part of their European vacation. Chief among them, Barbara Dennek plays the central tourist, also named Barbara, and was Tati’s neighbor and later his mistress. Barbara serves almost no purpose to the film except, like Hulot, to represent a familiar face onscreen for the audience to follow. Almost no comic gags revolve around her, and her presence is merely to be pretty and distracting. As a result, it’s easy to overlook Hulot’s entrance in the middle ground; Tati even tries to distract us when a Hulot look-alike drops his umbrella and the sound draws our attention. Hulot arrives in Paris by plane, having accepted a job as a car salesman as arranged by his brother-in-law from Mon oncle, a detail barely acknowledged in PlayTime. We first see him getting on a bus. And once Barbara’s group exits the antiseptic airport, the film expands into the larger world of Tativille, transitioning from one gag to another in a series of city streets, offices, a tradeshow exhibition, a modern apartment complex, a chic restaurant, and finally congested traffic as Barbara’s party departs the city. Even the thinly drawn narratives, if they can be called such a thing, from M. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon oncle seem pregnant with content in comparison to the plot developments, or lack thereof, in PlayTime. During the proceedings, Tati’s camera is placed at a distance in only master shots, allowing the viewer to find the story within the frame. He challenges us to find the gag and examine what’s going on, because the unobservant viewer may miss it.

As mentioned above, no real story exists in PlayTime. The events take place over a 24-hour period, a single day and evening, followed by a brief coda the next morning. A group of American tourists arrive in the Paris airport as part of their European vacation. Chief among them, Barbara Dennek plays the central tourist, also named Barbara, and was Tati’s neighbor and later his mistress. Barbara serves almost no purpose to the film except, like Hulot, to represent a familiar face onscreen for the audience to follow. Almost no comic gags revolve around her, and her presence is merely to be pretty and distracting. As a result, it’s easy to overlook Hulot’s entrance in the middle ground; Tati even tries to distract us when a Hulot look-alike drops his umbrella and the sound draws our attention. Hulot arrives in Paris by plane, having accepted a job as a car salesman as arranged by his brother-in-law from Mon oncle, a detail barely acknowledged in PlayTime. We first see him getting on a bus. And once Barbara’s group exits the antiseptic airport, the film expands into the larger world of Tativille, transitioning from one gag to another in a series of city streets, offices, a tradeshow exhibition, a modern apartment complex, a chic restaurant, and finally congested traffic as Barbara’s party departs the city. Even the thinly drawn narratives, if they can be called such a thing, from M. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon oncle seem pregnant with content in comparison to the plot developments, or lack thereof, in PlayTime. During the proceedings, Tati’s camera is placed at a distance in only master shots, allowing the viewer to find the story within the frame. He challenges us to find the gag and examine what’s going on, because the unobservant viewer may miss it.

To shoot the film, Tati’s choice to use 70mm panoramic stock could not have been more appropriate, more so than any other Tati picture, which were all shot in a box-like aspect ratio of 1:1.33. While the wider strip of film allowed for a greater sense of detail within the frame, the director’s choice was impelled by a desire to implement a rectangular widescreen format, since his other films has all been presented in the square 35mm standard of the era. Larger format film stock, especially 70mm, was usually reserved for larger-than-life box-office spectacles filled with grandiose imagery and crowd-pleasing adventure, such as Ben-Hur (1959) or Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Today, finding a movie theater with a 70mm projector capable of capturing its full visual bounty is rarer still. However, Tati described his implementation as follows: “What I find extraordinary is that the device allows the viewer to have a fuller appreciation of a mere pin dropping in a large empty room.” And so, Tati’s use of the frame does not direct the viewer toward the action as Hollywood spectacles do; rather, he carefully avoids close-ups, which he dreaded, and presents a whole environment onscreen in which the purpose of the scene is not emphasized or visually underlined. Our eyes are meant to explore, to regard the frame’s inhabitants and take note of the countless little scenarios and gags that Tati has dreamed up for us. Such a methodology remains unique in cinema and a testament to Tati’s art, and his ongoing pursuit to help his audiences identify the comic delights of everyday life.

In a sense, Tati’s film would most closely resemble Charles Chaplin’s Modern Times (1938), in that both films present modern industrial and technological amenities through satire. Chaplin poked fun at conveyor belts and invented absurd feeding machines, and his stance on the dehumanization of industrialism is unmistakable. But Tati explores architecture, transportation, and modern social behavior from a distance and allows his audience to note how problematic and illogical some modern apparatuses and conveniences may be, while he also approaches his subject with a sense of admiration. Indeed, much like Fritz Lang was purportedly inspired by the skyline of New York City before he made Metropolis (1927), Tati suggested that he was so fascinated by a trip to New York that he incorporated his feelings of captivation into PlayTime. At times, he engages in what Tati’s biographer David Bellos called “a critique of the inauthenticity and alienation of modern life.” Note that the presence of nature, specifically the absence of dogs (who are frequent players in Tati’s other films, specifically Mon oncle), are conspicuously absent in PlayTime—a solemn and understated reminder of what’s missing in the film’s world. The one and only instance of earthiness or nature is represented by a solitary flower stall, a frequent old Parisian association, which also happens to represent the brightest point of color in the entire picture. Colors of gray, black and white dominate the frame with rare appearances by other colors that seem to be muted anyway. At other times, he arranges a characteristically Tati-brand kind of magnificence in his gags formed around everyday life.

In a sense, Tati’s film would most closely resemble Charles Chaplin’s Modern Times (1938), in that both films present modern industrial and technological amenities through satire. Chaplin poked fun at conveyor belts and invented absurd feeding machines, and his stance on the dehumanization of industrialism is unmistakable. But Tati explores architecture, transportation, and modern social behavior from a distance and allows his audience to note how problematic and illogical some modern apparatuses and conveniences may be, while he also approaches his subject with a sense of admiration. Indeed, much like Fritz Lang was purportedly inspired by the skyline of New York City before he made Metropolis (1927), Tati suggested that he was so fascinated by a trip to New York that he incorporated his feelings of captivation into PlayTime. At times, he engages in what Tati’s biographer David Bellos called “a critique of the inauthenticity and alienation of modern life.” Note that the presence of nature, specifically the absence of dogs (who are frequent players in Tati’s other films, specifically Mon oncle), are conspicuously absent in PlayTime—a solemn and understated reminder of what’s missing in the film’s world. The one and only instance of earthiness or nature is represented by a solitary flower stall, a frequent old Parisian association, which also happens to represent the brightest point of color in the entire picture. Colors of gray, black and white dominate the frame with rare appearances by other colors that seem to be muted anyway. At other times, he arranges a characteristically Tati-brand kind of magnificence in his gags formed around everyday life.

Though it would be impossible and pointless to cover every gag or notable moment of humor in PlayTime, let’s consider just one ongoing theme—how a number of gags revolve around the city’s glass surfaces, their transparency and reflectivity. One man chases after an Hulot look-alike and slams his face into a glass door with a reverberating thud. Another brief moment has a doorman trying to light a cigarette, but when a passerby offers a light, he fails to realize that a glass window rests between them; he’s forced to walk around to the front door to lend his flame. Tati only shows us recognizable Paris monuments in reflections, such as the Eiffel Tower in a window, but all are illusions created artificially for the film. Another sequence features five workers holding a huge glass pane several stories up on a building under construction, and below a crowd gathers to watch a careful balancing act. As if dancing in an elaborate choreographed dance, the workers move back and forth, stepping in unison to install the glass, which, thanks to a complex back-lighting effect, was projected—in fact, the workers danced with nothing in their hands at all, the sequence designed to call our attention to the fanciful quality of the everyday movements all around us. Perhaps the finest, most whimsical use of glass in the picture belongs to a sequence near the end, where a window cleaner on a stepladder pivots a glass window as he wipes away, while outside a bus full of tourists ooh and aah at various unrelated sights. From outside, the reflection of the bus in the pivoting window appears to sway the passengers into the sky to a reflection of the clouds, and combined with jubilant sounds of the tourists, gives the impression of a rollercoaster ride that exists only as an optical illusion. Even more gags revolve around glass still, but who can list them all?

This is the meticulous genius of Jacques Tati, who could find beauty and amazement in combining something as simple as window cleaning and a banal bus tour. Throughout such sequences, Tati aligns us with other spectators onscreen. Take the men who play a circus high-wire tune on kazoos to score the dancing workers as they install the pane of glass. Tati frequently uses onlookers and silent observers to make us feel as though we are part of the crowd, looking-on at something commonplace but so quietly amusing that we might overlook its simple beauty. And yet, Tati does not reconstruct real-life events and present them in a documentary style. As much as he wants us to find the humor in everyday life, he’s not recreating it for us. His brand of comedy carefully assembles, piece by staged piece, an elaborate gag through seemingly effortless, but demanding constructions of visual and aural cues. Curious then that Hulot is not central to these gags; whereas, had Chaplin made the picture, his Little Tramp would be the progenitor of every laugh. Tati’s method throughout his work, and in PlayTime more than most, was to dispense the laughs among everyone onscreen as opposed to a central comic source. In M. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon oncle, several funny sequences exclude Hulot, but in PlayTime more gags occur without Hulot than with him. Tati employs false Hulots, loses Hulot in the crowd, sets Hulot behind other people, and allows him to disappear from the frame for several screen minutes at a time. Of course, Hulot’s awkward manner in the physical world of the city leads to a number of hilarious moments owed to the character, perhaps none funnier than Hulot trying to track down his business rendezvous in a maze of office cubicles and stairways.

This is the meticulous genius of Jacques Tati, who could find beauty and amazement in combining something as simple as window cleaning and a banal bus tour. Throughout such sequences, Tati aligns us with other spectators onscreen. Take the men who play a circus high-wire tune on kazoos to score the dancing workers as they install the pane of glass. Tati frequently uses onlookers and silent observers to make us feel as though we are part of the crowd, looking-on at something commonplace but so quietly amusing that we might overlook its simple beauty. And yet, Tati does not reconstruct real-life events and present them in a documentary style. As much as he wants us to find the humor in everyday life, he’s not recreating it for us. His brand of comedy carefully assembles, piece by staged piece, an elaborate gag through seemingly effortless, but demanding constructions of visual and aural cues. Curious then that Hulot is not central to these gags; whereas, had Chaplin made the picture, his Little Tramp would be the progenitor of every laugh. Tati’s method throughout his work, and in PlayTime more than most, was to dispense the laughs among everyone onscreen as opposed to a central comic source. In M. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon oncle, several funny sequences exclude Hulot, but in PlayTime more gags occur without Hulot than with him. Tati employs false Hulots, loses Hulot in the crowd, sets Hulot behind other people, and allows him to disappear from the frame for several screen minutes at a time. Of course, Hulot’s awkward manner in the physical world of the city leads to a number of hilarious moments owed to the character, perhaps none funnier than Hulot trying to track down his business rendezvous in a maze of office cubicles and stairways.

Tati’s genius for gags culminates in the last half of the film, which takes place in the posh Royal Garden restaurant, a pompous would-be hotspot nervously celebrating its opening night. Hulot gets drawn inside by the doorman, an old army buddy (Tony Andall), and witnesses, and certainly takes part in, a series of situations that accumulate to a disastrous opening, but a joyous evening nonetheless. Servers and diners both roam about in confusion. The bustle causes one table to watch as their order of the house special, the “Tubot à la Royale”, is wheeled over on a portable grill, warmed up, peppered, and basted on three separate occasions, and ultimately it’s never consumed; all while hungry patrons move about from table to table, everyone confused about where they should be seated and who’s serving who. As the evening goes on, the building all but falls apart: we see a freshly glued floor tile sticking to a server’s shoe, servers struggling to fit trays through the narrow kitchen entrance, wet paint on the chairs leaving faux pinstripes on the patrons’ backs, and the pronged crown-like backs of the chairs marking impressions on various diners. Throughout the evening, servers with torn or soiled clothes go outside on the balcony to hide from customers, and over the course of the evening each of them end up out there in a long procession of intervals, each giving their ruined item of clothing to a server whose remains outside, exchanging his clothes for ruined ones; by the end of the night, he’s in tatters. Outside, the spiraling neon light under the restaurant’s canopy, which is meant to direct pedestrians inside, directs drunkards leaving the Royal Garden to follow the light back in through its doors. And yet, bemused by everything falling apart around them, Hulot, Barbara, a bombastic American, and indeed all the patrons make a party of the restaurant’s increasingly disintegrating ambiance—Tati’s testament to the French spirit.

Tati’s money problems improved naught after PlayTime‘s first showings. Complaints that the film was too long resulted in Tati, who could nary afford to hire an editor, cutting down individual copies of the film from the original runtime of 140 minutes to under 120 minutes for general release. Tati assured the film community that the original 70mm negative remained in his possession, but after various re-releases in the decades to come, the longest cut yet released runs 124 minutes. At the time, Tati’s artistic integrity toward the project was both inspiring and debilitating. He intended PlayTime to be something new, a “spectacle cinématographique” featuring an exclusive first-run showing with reservable seats, something more along the lines of live theater. He refused to provide some cinemas unequipped with 70mm projectors an altered 35mm version, and audiences further confounded by the lacking presence of the beloved M. Hulot added to the lukewarm responses. After all, Hulot barely utters a word in the film; although Tati’s character says little in earlier incarnations, he at least spoke. And, in fact, the film’s only dialogue consists of background chatter that amounts to ambient noise. Moreover, Tati had become worn down not only by the production itself, but by the negative press surrounding its ostentatiousness. That he refused interviews or to allow journalists on his set worsened matters. Negative press both before and after its release soured audience reactions, and Tati’s financial troubles led to bankruptcy when he failed to secure a full U.S. distribution. Worse, shortly after its release, France was struck with the student revolts of May 1968 and everything else seemed unimportant. Not until years later, often after the required multiple viewings of PlayTime, did audiences and film scholars realize the film’s true mastery. In their 2012 poll of critics and directors, Sight & Sound, published by the British Film Institute, put PlayTime on their prestigious “Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time” list.

Tati’s money problems improved naught after PlayTime‘s first showings. Complaints that the film was too long resulted in Tati, who could nary afford to hire an editor, cutting down individual copies of the film from the original runtime of 140 minutes to under 120 minutes for general release. Tati assured the film community that the original 70mm negative remained in his possession, but after various re-releases in the decades to come, the longest cut yet released runs 124 minutes. At the time, Tati’s artistic integrity toward the project was both inspiring and debilitating. He intended PlayTime to be something new, a “spectacle cinématographique” featuring an exclusive first-run showing with reservable seats, something more along the lines of live theater. He refused to provide some cinemas unequipped with 70mm projectors an altered 35mm version, and audiences further confounded by the lacking presence of the beloved M. Hulot added to the lukewarm responses. After all, Hulot barely utters a word in the film; although Tati’s character says little in earlier incarnations, he at least spoke. And, in fact, the film’s only dialogue consists of background chatter that amounts to ambient noise. Moreover, Tati had become worn down not only by the production itself, but by the negative press surrounding its ostentatiousness. That he refused interviews or to allow journalists on his set worsened matters. Negative press both before and after its release soured audience reactions, and Tati’s financial troubles led to bankruptcy when he failed to secure a full U.S. distribution. Worse, shortly after its release, France was struck with the student revolts of May 1968 and everything else seemed unimportant. Not until years later, often after the required multiple viewings of PlayTime, did audiences and film scholars realize the film’s true mastery. In their 2012 poll of critics and directors, Sight & Sound, published by the British Film Institute, put PlayTime on their prestigious “Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time” list.

As with any film by Jacques Tati, the experience of PlayTime amounts to a series of moments and gags realized over a leisurely runtime. Some gags remain unresolved; consider how the table who ordered the Tubot à la Royale never tastes their over-seasoned fish. Tati does not always deliver the punch line; sometimes, the anticipation of the punch line is enough. He leaves it to his audience to find these moments within the film, and so active participation is required. Take the sequence where Hulot visits a friend’s apartment. Tati shoots from outside the building looking in at four boxy apartments à la Rear Window through the building’s huge windows. In one apartment, Hulot’s friend sits him down to watch television, looking right; on the other side of the wall, facing left, another family watches their television. But as both parties are separated by a wall, it looks as though they’re interacting—Tati’s sly commentary on the distance TV creates between people is poetic and hilarious. In one of the film’s rare uses of non-grayscale color, Hulot looks over a food selection in a cheap convenience store; above, a green neon pharmacy sign illuminates Hulot and the store’s food selections, the image remarking on the dull quality of such fast food and its sickening effect. And PlayTime‘s last grandiose sequence crams the tourists on a bus in a roundabout; cars, vans, and buses go round and around, caught in the circular traffic and unable to escape. All at once, music from a circus merry-go-round fills the soundtrack, and life becomes a carousel where the disagreeable reality of traffic congestion suddenly becomes an extraordinary event, a visual notion that perfectly summarizes the film’s themes.

Since his earliest work on Jour de fête (1949), Tati had considered himself a cinematic artist of the highest order, likening his approach to that of a fine artist more than a filmmaker. In an interview with French film critics in Cahier du cinéma, Tati said “I am in the position of a painter painting a canvas.” In particular, he described PlayTime as “abstract art,” and in terms of how his aesthetic approach innovates on the traditional methods of cinema, his remarks precisely illustrate how the film resists narrative in favor of a methodical and mannered formal technique. By placing his audience at a distance and allowing wonderfully choreographed moments to unfold before us—at once right in front of us yet hidden in plain sight so that we must find them within his generous frame—Tati transforms his spectators into participants of his absurdist and often purposeless spaces, which in turn are home to a procession of incredibly conceived gags, one after another. That Tati could not top PlayTime‘s massive scope or ambitious range in his subsequent films, Trafic (1971) and Parade (1974), goes without saying. This kind of film exists on a level all its own, like an art installation projected onto a screen by a 70mm projector, as it was meant to be seen or, for a lesser experience, on the largest possible screen at home. Through his film we smile and chuckle, fascinated by a fully realized world of details rich with Tati’s quizzical observations. And through his eyes and thus our own, everyday life becomes a recreational activity through which everyone is a spectator and participant, but only if we allow ourselves a moment to take notice.

Since his earliest work on Jour de fête (1949), Tati had considered himself a cinematic artist of the highest order, likening his approach to that of a fine artist more than a filmmaker. In an interview with French film critics in Cahier du cinéma, Tati said “I am in the position of a painter painting a canvas.” In particular, he described PlayTime as “abstract art,” and in terms of how his aesthetic approach innovates on the traditional methods of cinema, his remarks precisely illustrate how the film resists narrative in favor of a methodical and mannered formal technique. By placing his audience at a distance and allowing wonderfully choreographed moments to unfold before us—at once right in front of us yet hidden in plain sight so that we must find them within his generous frame—Tati transforms his spectators into participants of his absurdist and often purposeless spaces, which in turn are home to a procession of incredibly conceived gags, one after another. That Tati could not top PlayTime‘s massive scope or ambitious range in his subsequent films, Trafic (1971) and Parade (1974), goes without saying. This kind of film exists on a level all its own, like an art installation projected onto a screen by a 70mm projector, as it was meant to be seen or, for a lesser experience, on the largest possible screen at home. Through his film we smile and chuckle, fascinated by a fully realized world of details rich with Tati’s quizzical observations. And through his eyes and thus our own, everyday life becomes a recreational activity through which everyone is a spectator and participant, but only if we allow ourselves a moment to take notice.

Bibliography:

Bellos, David. Jacques Tati: His Life and Art. London: Harvill, 1999.

Chion, Michel. The Films of Jacques Tati. Toronto: Guernica, 1997.

Dondey, Marc. Jacques Tati. Paris: Ramsay, 1987.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review