The Definitives

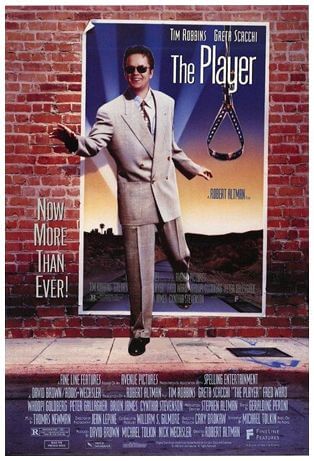

The Player

Essay by Brian Eggert |

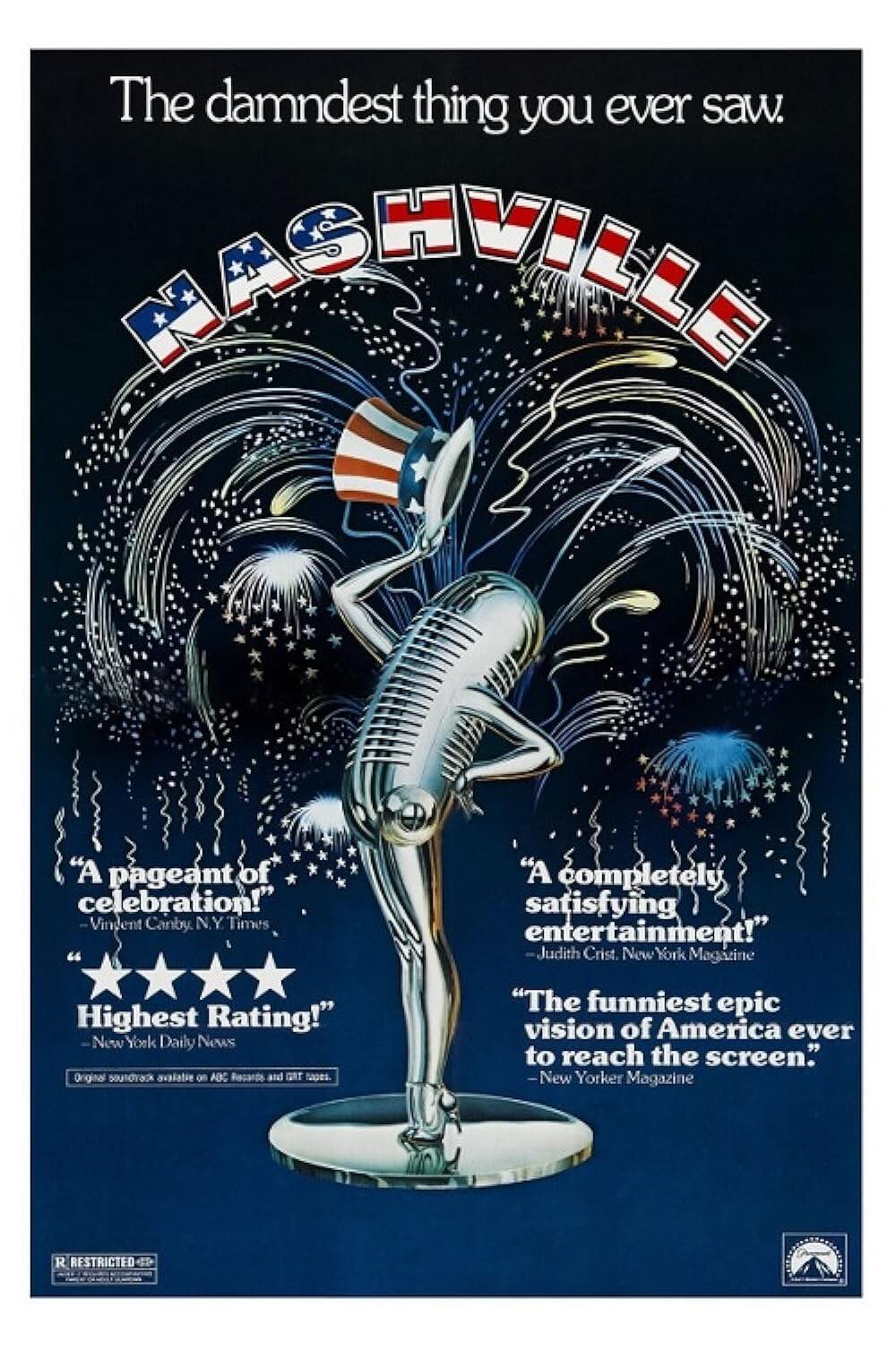

The Player opens with a crane shot that lasts over seven minutes, all filmed as one long take, much of it improvised, during which each moment sets up the film’s many plotlines and characters. The shot follows producers, screenwriters, actors, and executives on a studio lot. They discuss production snafus, potential projects, and even a death threat. The scene perfectly illustrates how the whole of Robert Altman’s film shifts from Hollywood satire to film noir, from comic farce to an almost dystopian portrait of tinsel town. In his masterful 1992 release, Altman investigates another curious subculture—just as he did in M*A*S*H (1970) and Nashville (1975)—by depicting Hollywood in the late 1980s and early 1990s: a place of excess, endless pitch sessions, power breakfasts, business lunches, ambitious execs, secluded spas, and vacuous celebrities, many of whom make cameo appearances as themselves. It’s also a story of murder and manipulation, and often a hilarious one. Altman once called it, “A very, very soft indictment of Hollywood.” However, even the most blackly comic murder has implications that could hardly be described as soft. What he meant was simple: Hollywood was much worse than he was representing in his film. After all, there was only one thing in Hollywood that could be considered worse than murder: releasing a flop. Through Altman’s incomparable perspective, The Player would become the ultimate post-modern insider’s film, whose deconstructive approach dishes on Hollywood culture in all its insidious glory.

Altman was the perfect choice to direct this material; his experiences with studios had been largely unpleasant. Flashback to 1979, after he directed several small, highly praised, financially lukewarm pictures (3 Women, A Wedding, Quintet, etc.). Altman wanted to prove he could draw box-office numbers and helmed Popeye. Although the film cost $20 million and earned back three times that, its performance was less than distributors at Paramount and Disney expected. Along with mixed critical assessments, the studios labeled Popeye as a bomb. For the remainder of the decade, Altman worked on several stage-to-screen adaptations and television projects far removed from his artistic and nonconformist work from the decade before, which included McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) and The Long Goodbye (1973). With something rare like his six-hour HBO miniseries Tanner ’88, a deft political satire far ahead of its time, he showed a glint of his former talents. But even the sharp material of Streamers (1983) and Secret Honor (1984) couldn’t rescue Altman or return him to Hollywood. To be sure, the wound of Popeye had stuck with him, and he literally moved away from Hollywood filmmaking when he began living in France. Lesser productions like the raunchy National Lampoon’s comedy O.C. and Stiggs (shot in 1984, shelved by MGM until 1987), the dry drama Fool for Love (1985), and the unfunny comedy Beyond Therapy (1987) flopped. However, Altman wanted to shoot in Hollywood again. He attempted to develop a sequel to Nashville with producer Jerry Weintraub in 1987, but all plans fell through when they could not reach an agreement on the script.

Cut to 1990, when Altman’s British miniseries Vincent & Theo was recut for theatrical release and brought him renewed attention. After the director moved back to the U.S. and established offices in Los Angeles, he began to develop several stories by Raymond Carver into something he called “L.A. Shortcuts” (eventually Short Cuts, 1993), but he couldn’t acquire financing—although he had several actors, such as Tim Robbins, lined-up to star. Instead, Fine Line Features, an offshoot of New Line Cinema, offered Altman the chance to direct a screenplay by Michael Tolkin called The Player, based on his 1988 novel—which was to be in the vein of other showbiz films like All About Eve (1950) or The Bad and the Beautiful (1952). Negotiations with their first choice of filmmaker, Sidney Lumet, fell through because of Lumet’s salary demands. Altman, who hadn’t had a hit in years and was left veritably ostracized from Hollywood, took one-fourth of Lumet’s proposed paycheck of $2 million. Altman didn’t care much for Tolkin’s script but loved the subject matter. His producer David Brown told him, “You were born to direct this.” Altman worked on the script, hiring some dialogue writers and working with Tolkin on the story’s structure. Altman continued with rewrites well into production, gradually turning Tolkin’s story into a film-about-film into a scathing Hollywood portrait. Although, reducing the film to just one of its many forms is a mistake; it’s also a romance, a thriller, a comedy, “but with a heart”—as one of its characters might say.

Cut to 1990, when Altman’s British miniseries Vincent & Theo was recut for theatrical release and brought him renewed attention. After the director moved back to the U.S. and established offices in Los Angeles, he began to develop several stories by Raymond Carver into something he called “L.A. Shortcuts” (eventually Short Cuts, 1993), but he couldn’t acquire financing—although he had several actors, such as Tim Robbins, lined-up to star. Instead, Fine Line Features, an offshoot of New Line Cinema, offered Altman the chance to direct a screenplay by Michael Tolkin called The Player, based on his 1988 novel—which was to be in the vein of other showbiz films like All About Eve (1950) or The Bad and the Beautiful (1952). Negotiations with their first choice of filmmaker, Sidney Lumet, fell through because of Lumet’s salary demands. Altman, who hadn’t had a hit in years and was left veritably ostracized from Hollywood, took one-fourth of Lumet’s proposed paycheck of $2 million. Altman didn’t care much for Tolkin’s script but loved the subject matter. His producer David Brown told him, “You were born to direct this.” Altman worked on the script, hiring some dialogue writers and working with Tolkin on the story’s structure. Altman continued with rewrites well into production, gradually turning Tolkin’s story into a film-about-film into a scathing Hollywood portrait. Although, reducing the film to just one of its many forms is a mistake; it’s also a romance, a thriller, a comedy, “but with a heart”—as one of its characters might say.

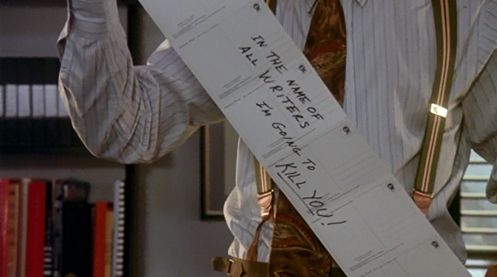

When Altman describes the film as a “very soft indictment of Hollywood,” he wants the viewer to be caught off guard by how much worse it is, and then force us to consider: If this is “soft”, then what must Hollywood really be like? At the center, Tim Robbins stars as the studio’s yuppie vice president Griffin Mill. He’s introduced during the opening tracking shot, which, as mentioned, lasts over seven minutes, much like the opener of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958). Knowingly, Altman’s characters talk about long takes, specifically referencing Welles’ film. Elsewhere, Griffin hears pitches from various writers. Buck Henry suggests “The Graduate, Part 2” about Ben and Elaine, who eloped in the original, but twenty-five years later, they are living with Mrs. Robinson. She’s “had a stroke… so can’t talk… It’ll be funny. Dark, weird, and funny. And with a stroke.” Distant, Griffin listens and nods, “I like it, I like it.” Griffin has good reason to feel detached. He’s received another in a series of poison pen messages, each delivered on a postcard. “On behalf of all writers, I am going to kill you!” one of them reads. Griffin’s job involves determining which pitches his studio will produce; he listens to thousands every year and can only choose twelve. Evidently, Griffin listened to a screenwriter’s pitch, made promises to follow-up, but then ignored the writer, and now the writer is sending him death threats.

Once a major cog at his studio, Griffin feels pressure on all fronts. Cocksure executive Larry Levy (Peter Gallagher) has just transferred from Fox, and there’s rumor that Levy is poised to replace Griffin. His romantic relationship to story editor Bonnie Sherow (Cynthia Stevenson) feels strained. And the postcards keep coming. After some investigating, Griffin believes the aggrieved writer might be David Kahane (Vincent D’Onofrio) and calls to talk things over, but instead speaks to the writer’s significant other, June Gudmundsdottir (Greta Scacchi), an intriguing painter uninterested in Hollywood. Griffin learns from June that Kahane has gone to see a movie in Pasadena, and so Griffin drives out to confront him. Over drinks, he tries to give Kahane a deal if the threats stop, but the writer throws the offer in Griffin’s face. Around the corner in a parking lot, their confrontation becomes physical. Griffin goes too far and kills the writer. In a panic, he stages the scene to look like a mugging-gone-wrong. The next morning in a meeting of studio executives, Griffin arrives late and must nervously endure Levy’s idea to get rid of writers and instead conceive stories from the headlines—one of which is a report of Kahane’s murder. Still, Griffin maintains his calm: “If we can just get rid of these actors and directors, I think we’ve got something here.”

Once a major cog at his studio, Griffin feels pressure on all fronts. Cocksure executive Larry Levy (Peter Gallagher) has just transferred from Fox, and there’s rumor that Levy is poised to replace Griffin. His romantic relationship to story editor Bonnie Sherow (Cynthia Stevenson) feels strained. And the postcards keep coming. After some investigating, Griffin believes the aggrieved writer might be David Kahane (Vincent D’Onofrio) and calls to talk things over, but instead speaks to the writer’s significant other, June Gudmundsdottir (Greta Scacchi), an intriguing painter uninterested in Hollywood. Griffin learns from June that Kahane has gone to see a movie in Pasadena, and so Griffin drives out to confront him. Over drinks, he tries to give Kahane a deal if the threats stop, but the writer throws the offer in Griffin’s face. Around the corner in a parking lot, their confrontation becomes physical. Griffin goes too far and kills the writer. In a panic, he stages the scene to look like a mugging-gone-wrong. The next morning in a meeting of studio executives, Griffin arrives late and must nervously endure Levy’s idea to get rid of writers and instead conceive stories from the headlines—one of which is a report of Kahane’s murder. Still, Griffin maintains his calm: “If we can just get rid of these actors and directors, I think we’ve got something here.”

Meanwhile, the studio’s security chief (Fred Ward) and Pasadena detectives question Griffin about what happened the night before with Kahane, but he denies any culpability and suggests they departed from their meeting peacefully. Even while maintaining his composure, he cannot help but seek out June, an unremorseful sort who quickly allows herself to become romantically involved with Griffin, and takes his mind away from the mounting pressure. At the same time, a strange man (Lyle Lovett) has been following Griffin, and what’s worse, the poison pen letters continue—which means Kahane wasn’t the writer after all. As for his problems at the studio, Griffin sees a way out when he hears a pitch for a socially conscious picture called “Habeas Corpus” and sets Levy up to develop it, eventually leading to his takeover of the studio. His love affair with June takes off, though Griffin’s betrayal crushes Bonnie. And fortunately, the sole eyewitness to Kahane’s murder proves unreliable; she picks Lovett’s character, an oddball detective, from a lineup, and forces investigators to clear Griffin of any suspicion. Griffin has gotten away with murder.

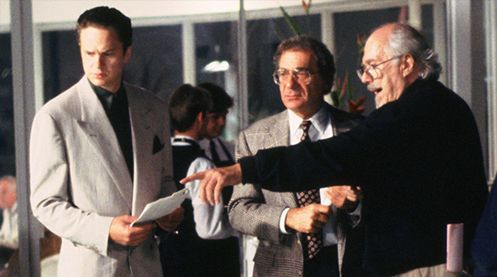

Altman wanted Robbins to play Griffin after seeing Bull Durham (1988) and almost walked away from the production when Robbins wasn’t on the studio’s approved list of actors for the lead—a risky move, considering Altman needed the work. Nevertheless, the studio wanted Altman, and they gave him his actor. “Eighty percent of my creative function or work is finished the moment I get the film cast,” Altman once said. With a cast capable of improvisation, Altman guided his ensemble through a creative shooting method. And while The Player at times seems meticulously scripted, Altman demanded his cast bring the material to life through their own flourishes. “I try to make the film knowing that I have the script as a platform, something to fall back on,” said Altman. “It’s a working process, not a fixed text.” Everyone on Altman’s sets knows their general mark and what they’re supposed to do for a given scene; they know the script, but they’re also expected to improvise. Altman wants his film to live and breathe. Robbins observed, “It’s a live organism making a film, and in Bob’s world it couldn’t remain static, it couldn’t remain the same, it had to keep evolving daily. The basic situations were there, the basic scene structure was there, but I think he thought a lot of it just sounded like written dialogue and it wasn’t organic enough, and so we had to figure out how to get there.” Altman’s style earns common comparisons to a jazz composer, since both use variations and improvisations on a theme. Altman considers himself “a liar”. As he explains, “When they say, ‘Are you going to do this picture the way the script is?’ Then I say, ‘You’re goddamn right I am.’ …And I mean that, sort of… but I know it’s going to get better [than the script].”

Altman wanted Robbins to play Griffin after seeing Bull Durham (1988) and almost walked away from the production when Robbins wasn’t on the studio’s approved list of actors for the lead—a risky move, considering Altman needed the work. Nevertheless, the studio wanted Altman, and they gave him his actor. “Eighty percent of my creative function or work is finished the moment I get the film cast,” Altman once said. With a cast capable of improvisation, Altman guided his ensemble through a creative shooting method. And while The Player at times seems meticulously scripted, Altman demanded his cast bring the material to life through their own flourishes. “I try to make the film knowing that I have the script as a platform, something to fall back on,” said Altman. “It’s a working process, not a fixed text.” Everyone on Altman’s sets knows their general mark and what they’re supposed to do for a given scene; they know the script, but they’re also expected to improvise. Altman wants his film to live and breathe. Robbins observed, “It’s a live organism making a film, and in Bob’s world it couldn’t remain static, it couldn’t remain the same, it had to keep evolving daily. The basic situations were there, the basic scene structure was there, but I think he thought a lot of it just sounded like written dialogue and it wasn’t organic enough, and so we had to figure out how to get there.” Altman’s style earns common comparisons to a jazz composer, since both use variations and improvisations on a theme. Altman considers himself “a liar”. As he explains, “When they say, ‘Are you going to do this picture the way the script is?’ Then I say, ‘You’re goddamn right I am.’ …And I mean that, sort of… but I know it’s going to get better [than the script].”

Sure enough, Tolkin complained that the dailies didn’t resemble his script; producer David Brown was also very concerned. Finally, Altman admitted he had no intention of shooting the script page-to-screen. Altman reminded Brown that he did the same thing on M*A*S*H, and that Ring Lardner didn’t complain when he won the Academy Award for Best Screenplay. Indeed, Altman and his cast were making things up as they went along, which lends the film an incredible sense of on-set camaraderie, as though everyone’s in on the same joke. Further, given the subject matter and Hollywood’s affinity for films about film, Altman was able to secure himself celebrity cameos in which stars played themselves. When word got out around Hollywood about the energy and magic in the dailies, actors who wanted to appear in a cameo started calling. Altman thought it was absurd for the story’s characters to name actors who weren’t real, so he arranged sixty cameos in all, each performer improvising their own lines and scenes. The list of cameos goes on and on, extending from Altman’s once and future stock company to those who simply agreed to play themselves onscreen: Lily Tomlin, Jeff Goldblum, Cher, John Cusack, Peter Falk, Angelica Huston, Jack Lemmon, Malcolm McDowell, Nick Nolte, Marlee Matlin, and Harry Belafonte, among dozens of others. The only actor Altman wanted but who refused to appear in the film was Arnold Schwarzenegger. All other cameos appeared for cost; he even convinced several actors to donate their salaries. He could generate an unbelievable amount of goodwill through loyalty and making the work enjoyable. In many cases, such as the final sequence from “Habeas Corpus”, he shot without teamsters and built a set without a Hollywood lot to save on costs.

Altman noted: “It’s the doing that’s the important thing. I equate film-making with sandcastles. You get a bunch of mates together and go down to the beach and build a great sandcastle. You sit back and have a beer, the tide comes in, and in twenty minutes it’s just smooth sand. That structure you made is in everybody’s memories, and that’s it. You all start walking home, and someone says ‘Are you going to come back next Saturday and build another one?’ And another guy says, ‘Well, OK, but I’ll do moats this time, not turrets!’ But that, for me, is the real joy of it all, that it’s just fun, and nothing else… If I look back at all my work, it all seems like yesterday. I can’t imagine how all this time got away. All of it is basically the same; none of it comes from any brilliance. It comes from enthusiasm, a little bit of ego and tenacity.” No wonder he named his production company Sandcastle 5 Production. He goes on to compare watching a film to listening to a piece of music. “You don’t remember a piece of music from hearing it once.” Indeed, The Player contains a million fascinating touches, Altman’s actors and cameos filling the frame, his signature overlapping dialogue, the conspicuously subtle mise-en-scène that makes the Hollywood backdrop so believable. His camera roams around a large canvas, zooming quite unceremoniously onto a subject or significant detail to make often enlightening associations. Amid all the detail and life onscreen, Altman’s themes remain somewhat elusive, even more so because he often refused to discuss his work in any analytical way.

Altman noted: “It’s the doing that’s the important thing. I equate film-making with sandcastles. You get a bunch of mates together and go down to the beach and build a great sandcastle. You sit back and have a beer, the tide comes in, and in twenty minutes it’s just smooth sand. That structure you made is in everybody’s memories, and that’s it. You all start walking home, and someone says ‘Are you going to come back next Saturday and build another one?’ And another guy says, ‘Well, OK, but I’ll do moats this time, not turrets!’ But that, for me, is the real joy of it all, that it’s just fun, and nothing else… If I look back at all my work, it all seems like yesterday. I can’t imagine how all this time got away. All of it is basically the same; none of it comes from any brilliance. It comes from enthusiasm, a little bit of ego and tenacity.” No wonder he named his production company Sandcastle 5 Production. He goes on to compare watching a film to listening to a piece of music. “You don’t remember a piece of music from hearing it once.” Indeed, The Player contains a million fascinating touches, Altman’s actors and cameos filling the frame, his signature overlapping dialogue, the conspicuously subtle mise-en-scène that makes the Hollywood backdrop so believable. His camera roams around a large canvas, zooming quite unceremoniously onto a subject or significant detail to make often enlightening associations. Amid all the detail and life onscreen, Altman’s themes remain somewhat elusive, even more so because he often refused to discuss his work in any analytical way.

Viewers must see Altman’s films twice, at least. As Altman once explained, during the first viewing “you’re going through the film and finding out how all these suppositions are wrong.” But the second time, “you’re not faked out by the plot, you’re able to deal with corners of the frame, with the nuances—which is what I feel the film is really about.” Audiences rarely embrace his films upon their initial release; appreciation grows over time after multiple viewings, after the audience has had time to consider more of the living world Altman has orchestrated and captured on film. “It’s a dilemma,” Altman remarked. “Do I worry that people are only going to see it once? Or do I go my way and think about the twenty-five people who might see it again and say, ‘Hey, that was good!’” Altman’s solution to this dilemma has always been to go his way. More often than not, critics respond well to his films. The Player was highly celebrated upon its release and in recent years named one of the finest films of the 1990s by several sources. At its Cannes Film Festival debut, Altman won Best Director and Robbins won Best Actor. Everyone in attendance declared “Altman’s back” and, as a result, the director sold concepts for Short Cuts and Kansas City. But he took exception to the notion of a comeback (“A comeback? I haven’t been anywhere. I’ve been working.”). For Altman, the work is important, not the recognition. At the 1993 Oscar ceremony, he and his wife, Kathryn Reed Altman, knew he wasn’t likely to win against the year’s favorite, Clint Eastwood for Unforgiven. And so, Kathryn baked them pot brownies, and they enjoyed their edibles during the show. By the end, they were enthusiastically cheering when Eastwood won Best Director.

Though Altman would never admit it nor discuss the film in much detail, The Player’s satire is acidic without being vulgar, sharp without being ugly. There’s a wit in its casting and a wry, but angry commentary lingering beneath the surface of each scene. As Griffin tries to find a great screen story, Altman shows us how Hollywood tries to discover a diamond-encrusted formula by looking at what was successful before and trying to repeat that formula. “It’s who you put in it and what the ad’s going to be,” said Altman. “They’re not going to read the script. They’re incapable of it.” The pitches are equally insubstantial, delivered in the form of this-meets-that comparisons to winning examples that came before, or just description of who should star: “We should get Lilly, Dolly, Goldie… Or Julia.” Knowing what was expected of him with a film like The Player, Altman worked against expectations, sometimes by embracing happy accidents, sometimes by design; having a written script meant a series of preconceived ideas that Altman wanted to subvert, leading to a wealth of on-set improvisation.

For example, Greta Scacchi was a sex symbol, widely known for appearing in many nude scenes, especially in European productions. But when it came to shooting a love scene between Griffin and June, Altman famously shot them from the neck up in a tight, sweaty close-up. Scacchi was pregnant at the time and refused to appear nude. Instead, he asked Cynthia Stevenson to appear topless, because her very neighborly appearance wasn’t what Hollywood was accustomed to seeing, and The Player isn’t about giving the viewer what they expect. Elsewhere, the director intentionally went out of his way to cast against type, such as hiring Whoopi Goldberg as the cop who investigates Griffin’s case or country singer Lyle Lovett, who had never acted before, as her partner. Their scenes in the police station with the nervous Griffin remain hilariously off-kilter, as Lovett swats flies and likens himself to Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), while Goldberg searches for a tampon and, after finding one, begins twirling it on the string. Another example of Altman toying with expectations: he knowingly cast Brion James as the studio president, realizing audiences would recognize him as the shoot-em-up villain from Red Heat (1988) and Tango & Cash (1989)—the director also found humor in casting a replicant from Blade Runner (1982) as a studio head. In this case, the casting is the extratextual commentary.

For example, Greta Scacchi was a sex symbol, widely known for appearing in many nude scenes, especially in European productions. But when it came to shooting a love scene between Griffin and June, Altman famously shot them from the neck up in a tight, sweaty close-up. Scacchi was pregnant at the time and refused to appear nude. Instead, he asked Cynthia Stevenson to appear topless, because her very neighborly appearance wasn’t what Hollywood was accustomed to seeing, and The Player isn’t about giving the viewer what they expect. Elsewhere, the director intentionally went out of his way to cast against type, such as hiring Whoopi Goldberg as the cop who investigates Griffin’s case or country singer Lyle Lovett, who had never acted before, as her partner. Their scenes in the police station with the nervous Griffin remain hilariously off-kilter, as Lovett swats flies and likens himself to Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), while Goldberg searches for a tampon and, after finding one, begins twirling it on the string. Another example of Altman toying with expectations: he knowingly cast Brion James as the studio president, realizing audiences would recognize him as the shoot-em-up villain from Red Heat (1988) and Tango & Cash (1989)—the director also found humor in casting a replicant from Blade Runner (1982) as a studio head. In this case, the casting is the extratextual commentary.

Richard E. Grant plays a writer-director named Tom Oakley, the sort who talks about specific scenes from Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood as if everyone was so familiar. Oakley represented how Altman felt about most Hollywood types: “That’s what all directors say! ‘I want this to be new’, ‘Everything for art’, and then in the end we sell out.” Consider how a running joke in the film revolves around every male lead role is “perfect for” Bruce Willis, while every female lead role is ideal for Julia Roberts, both of whom were at their height of popularity in 1992. But Oakley insists no celebrities should appear in “Habeas Corpus” to preserve the integrity of its social message. Of course, Roberts and Willis nab the key roles in scenes from “Habeas Corpus”—Altman’s satiric film-within-a-film. Roberts is escorted from her death row cell to the gas chamber as witnesses Susan Sarandon and Peter Falk watch. Guards Rene Auberjonois and Louise Fletcher ensure she’s strapped down and sealed inside. Gas begins to fill the chamber. All at once, district attorney Bruce Willis rushes into the scene, grabs a shotgun and shoots the glass, and then rescues Roberts. “Took you long enough,” she says. “Traffic was a bitch,” he replies. They kiss. The End. The last scene of “Habeas Corpus” is everything people like Griffin and Oakley initially feared, but because the film will undoubtedly be a hit, the studio is happy, and so the filmmakers are happy. Griffin and Oakley have sold out. Only Bonnie protests, and she’s summarily fired.

And yet, The Player’s brilliant ending is not without hope (thanks to a finale Altman and Robbins conceived over a joint). But it’s a sardonic kind of hope. A year later, the seemingly forgotten poison pen writer calls Griffin and pitches the concept for the film we just watched, about a Hollywood executive who kills the wrong writer. Griffin is intrigued, but only if the voice on the other end can “guarantee a happy ending.” The writer says he can, meaning Griffin will finally get away with his murder. Griffin makes the deal, and then he pulls into his driveway, where he’s greeted by June, now pregnant. “What took you so long?” she asks. “Traffic was a bitch,” he replies, mirroring the finale of “Habeas Corpus”. The Player’s final moment is both cynical and, knowingly, a required happy ending. Earlier, Griffin explained that Hollywood has a long history of gangster films, but that gangsters were always punished for their crimes, which is the expected, pseudo-happy ending for a Hollywood gangster film. Because Griffin has committed a murder, we might expect The Player to end with Griffin receiving his comeuppance. But the happy ending here features Griffin, the criminal, getting away with it. Though not the typical ending for a Hollywood production, it’s a happy ending nonetheless, being both a Hollywood crowd-pleaser and subversive at the same time.

And yet, The Player’s brilliant ending is not without hope (thanks to a finale Altman and Robbins conceived over a joint). But it’s a sardonic kind of hope. A year later, the seemingly forgotten poison pen writer calls Griffin and pitches the concept for the film we just watched, about a Hollywood executive who kills the wrong writer. Griffin is intrigued, but only if the voice on the other end can “guarantee a happy ending.” The writer says he can, meaning Griffin will finally get away with his murder. Griffin makes the deal, and then he pulls into his driveway, where he’s greeted by June, now pregnant. “What took you so long?” she asks. “Traffic was a bitch,” he replies, mirroring the finale of “Habeas Corpus”. The Player’s final moment is both cynical and, knowingly, a required happy ending. Earlier, Griffin explained that Hollywood has a long history of gangster films, but that gangsters were always punished for their crimes, which is the expected, pseudo-happy ending for a Hollywood gangster film. Because Griffin has committed a murder, we might expect The Player to end with Griffin receiving his comeuppance. But the happy ending here features Griffin, the criminal, getting away with it. Though not the typical ending for a Hollywood production, it’s a happy ending nonetheless, being both a Hollywood crowd-pleaser and subversive at the same time.

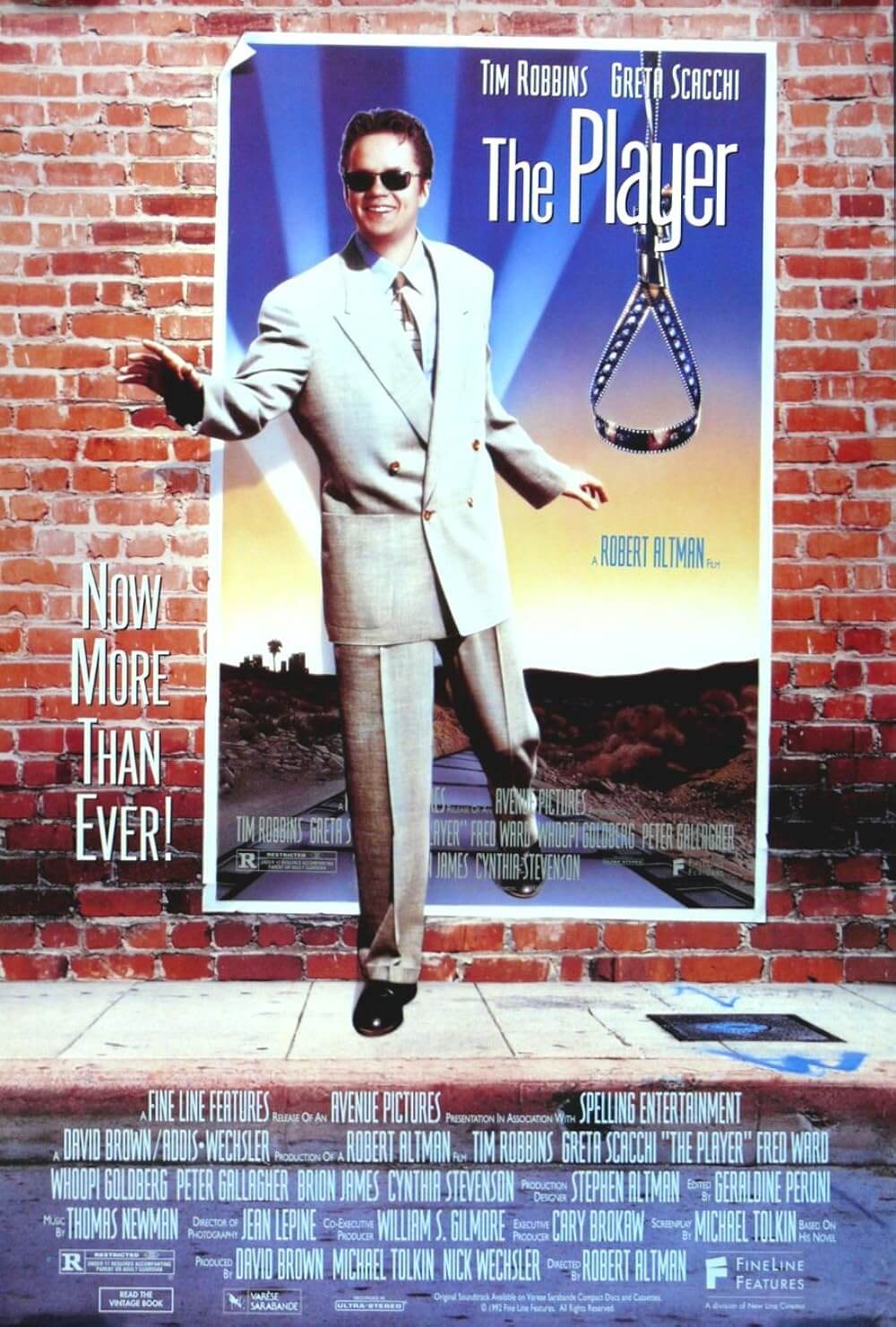

Had The Player been a standard Hollywood film, or the director a more conventional kind of filmmaker, the conclusion would have found Griffin paying for his crimes. Instead, the ending is both reality and fantasy, because Hollywood, in reality, continues to commit artistic crimes and rarely must answer for them, whereas Griffin’s dreamy situation in the last moments is pure fantasy. At one point, he tells June there are “certain elements that we need to market a film successfully… suspense, laughter, violence. Hope, heart. Nudity, sex. Happy endings… Mainly happy endings.” Griffin remains split down the middle. A romantic part of him believes in the artistic integrity of films, and yet he recognizes they are products manufactured by the studio. At an event he arranges for the preservation of film, he delivers a speech about artistic integrity (“Movies are art… Now more than ever”) and making socially responsible pictures. Regardless, Griffin will sell out without much difficulty. “Hollywood is much crueler and uglier and more calculating than you see in the film,” Altman once said. “It’s all about greed, really, the biggest malady of our civilization, and it was Hollywood as a metaphor for our society.” Altman believed Hollywood had a shameless ability to self-aggrandize. Just look at the false motto of Griffin’s studio: “Movies—now more than ever.”

This ugly, cruel streak running through The Player gives way to its darker aspects—it’s more noirish, suspenseful, and paranoid moments. Before he’s revealed to be a cop, the scenes with Lovett’s character shadowing Griffin contain an uneasy quality, in part because Lovett is an odd-looking man (his part in Short Cuts underscores that notion), and in part because Griffin builds up these moments as something more. Altman accelerates our paranoia when his frame stops on posters for classic crime thrillers like Murder in the Big House (1942) or merely a photo of Alfred Hitchcock to create an unconscious, rampant suspense. Altman also uses familiar noir visual devices to emphasize this feeling, such as shining light through the blinds in Griffin’s dark office, calling back to Double Indemnity (1944). At one point, the frame stops on a poster of Fritz Lang’s M (1931), a film whose title refers to a murderer, played by Peter Lorre, who is pursued in a manhunt for the film’s duration. A few scenes later, Griffin is referred to as “Mr. M” by employees at a secluded spa. Of course, through the Hollywood hullabaloo, the viewer almost forgets Griffin spends the entire film trying to get away with killing a man. But The Player’s thriller qualities service the notion of Hollywood’s role as a villain in the artist’s world—the great corruptor of a corrupt society, as Altman sees it.

This ugly, cruel streak running through The Player gives way to its darker aspects—it’s more noirish, suspenseful, and paranoid moments. Before he’s revealed to be a cop, the scenes with Lovett’s character shadowing Griffin contain an uneasy quality, in part because Lovett is an odd-looking man (his part in Short Cuts underscores that notion), and in part because Griffin builds up these moments as something more. Altman accelerates our paranoia when his frame stops on posters for classic crime thrillers like Murder in the Big House (1942) or merely a photo of Alfred Hitchcock to create an unconscious, rampant suspense. Altman also uses familiar noir visual devices to emphasize this feeling, such as shining light through the blinds in Griffin’s dark office, calling back to Double Indemnity (1944). At one point, the frame stops on a poster of Fritz Lang’s M (1931), a film whose title refers to a murderer, played by Peter Lorre, who is pursued in a manhunt for the film’s duration. A few scenes later, Griffin is referred to as “Mr. M” by employees at a secluded spa. Of course, through the Hollywood hullabaloo, the viewer almost forgets Griffin spends the entire film trying to get away with killing a man. But The Player’s thriller qualities service the notion of Hollywood’s role as a villain in the artist’s world—the great corruptor of a corrupt society, as Altman sees it.

In the years since The Player’s release, some of its allusions to Hollywood have worn out, such as the notion that the right celebrity can carry any film. With countless flops attributed to ‘90s mega-stars like Will Smith, Tom Cruise, and especially Julia Roberts and Bruce Willis (the latter has become a major direct-to-video star as of late), Hollywood now knows celebrities aren’t immune to flops. But franchises usually are, which is why superhero movies and YA books-to-film reign supreme at the box-office, even critically panned examples. At the same time, Hollywood’s emphasis on franchises has turned everything into a niche market. Dramas with gravitas, dark comedies, character studies, and anything outside of the obviously bankable may receive a limited theatrical release paired with a simultaneous debut on various video-on-demand services. Now more than ever, Hollywood scrambles to find the right blockbuster franchise formula, the next Star Wars or Harry Potter title that will carry on for a half-dozen or more sequels and generate hundreds of millions in worldwide receipts. Along with remakes, a call for happier endings, and generally blander material, Hollywood today plays it safe, even safer than the satiric Hollywood of The Player. Consider how Griffin makes a flippant remark about remaking Bicycle Thieves (1948), but then in 2011, A Better Life ostensibly remade Vittorio De Sica’s Italian neorealist classic by setting the story in Los Angeles. Nothing is sacred in Hollywood.

Before The Player’s title card appears onscreen in the first scene, the audience hears rumbling behind the camera, and then finally a film slate comes into frame, and the director’s voice announces, “Action!” The slate clap marks the time, and the film begins. Robert Altman wants his audience to engage with his picture on two concurrent levels: First, through Griffin’s noirish, nasty comic experiences getting away with murder, falling in love, and conquering his Hollywood studio; and second, he wants us to remember that every scene has been engineered in the filmmaking process, thus underscoring the film’s darkly satiric nature. From this first moment onward, Altman turns film conventions on their head; he consistently breaks the rules in provocative ways, using bravura technical trickery and inspired, often hilarious narrative turns. Through his impressionistic technique, the director demonstrates his rare ability to employ a spontaneous approach, and yet he produces a picture that feels meticulously staged and preplanned for a singular mission. In the end, Altman’s most genius trick is his use of Hollywood itself to declare the ugliness of the film industry’s greed and corruption of art. Fortunately, then and even today, there are rare pictures like The Player to give hope that artistic cinema is not dead.

Before The Player’s title card appears onscreen in the first scene, the audience hears rumbling behind the camera, and then finally a film slate comes into frame, and the director’s voice announces, “Action!” The slate clap marks the time, and the film begins. Robert Altman wants his audience to engage with his picture on two concurrent levels: First, through Griffin’s noirish, nasty comic experiences getting away with murder, falling in love, and conquering his Hollywood studio; and second, he wants us to remember that every scene has been engineered in the filmmaking process, thus underscoring the film’s darkly satiric nature. From this first moment onward, Altman turns film conventions on their head; he consistently breaks the rules in provocative ways, using bravura technical trickery and inspired, often hilarious narrative turns. Through his impressionistic technique, the director demonstrates his rare ability to employ a spontaneous approach, and yet he produces a picture that feels meticulously staged and preplanned for a singular mission. In the end, Altman’s most genius trick is his use of Hollywood itself to declare the ugliness of the film industry’s greed and corruption of art. Fortunately, then and even today, there are rare pictures like The Player to give hope that artistic cinema is not dead.

Bibliography:

McGilligan, Patrick. Robert Altman: Jumping Off the Cliff. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1989.

Thompson, David (edited by). Altman on Altman. London: Faber and Faber, 2006.

Zuckoff, Mitchell. Robert Altman: The Oral Biography. New York: Random House, 2009.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review