The Definitives

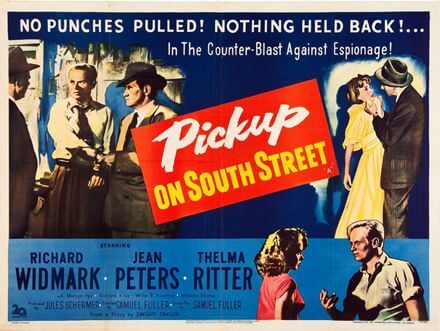

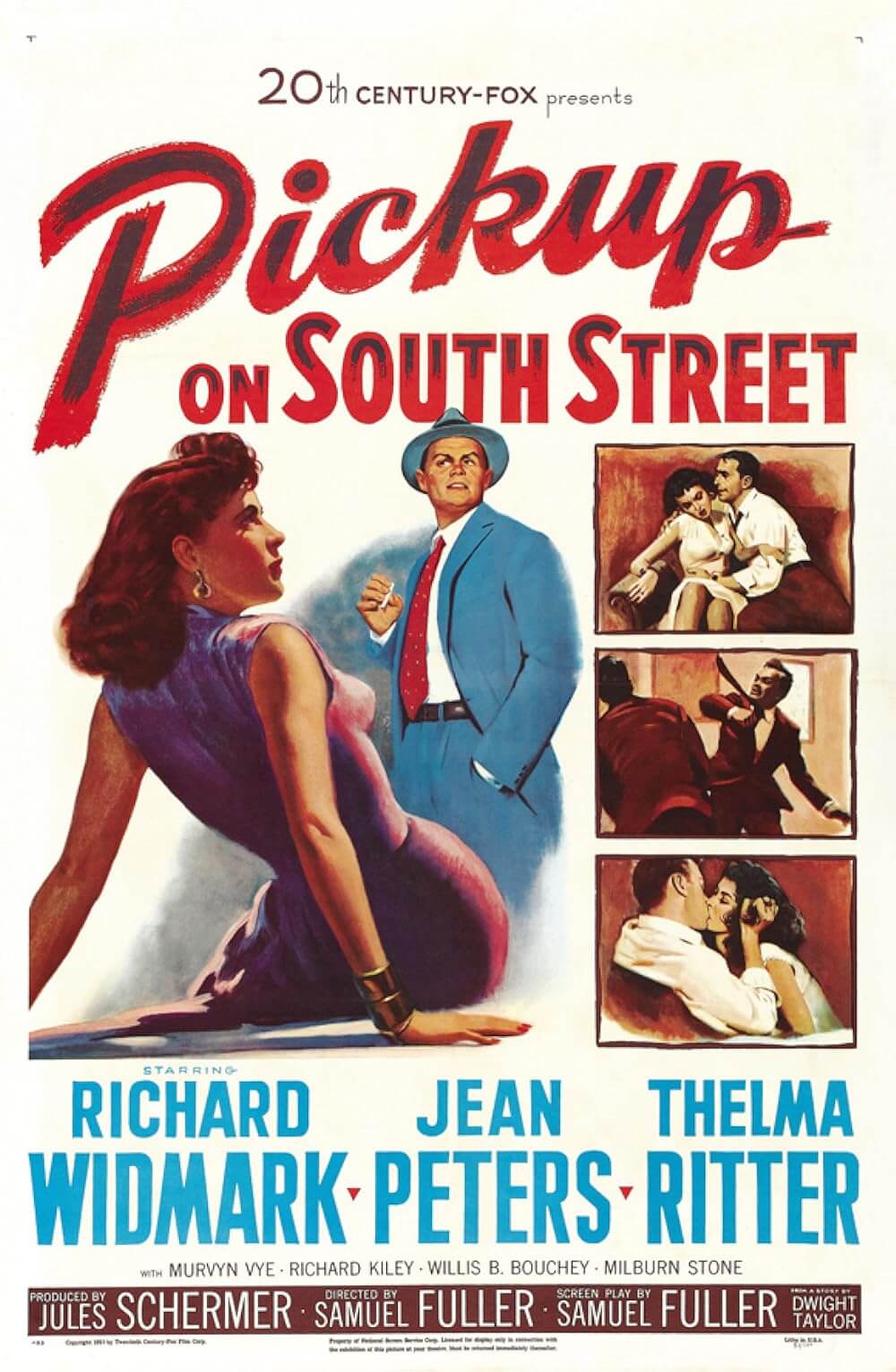

Pickup on South Street

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Samuel Fuller made films about survivors. Whether they tromped through the perils of war and came out alive or faced up against one of society’s more menacing social problems, his brand of hard-boiled characters and roughneck scenarios operate on instinct and pure emotion. Having seen it all, from blood-soaked battlefields to the likewise drenched urban sprawl, Fuller writes experience into his screenplays and directs them with authenticity and visual dynamism. His yarns are designed to disquiet his viewers, to “grab audiences by the balls” and not let go. Such is the case with Pickup on South Street, a film that spits in the face of patriotism in favor of human survival. Backed by his longtime supporter Daryl F. Zanuck at Twentieth Century Fox, Fuller was hired to rewrite Harry Brown’s script based on Dwight Taylor’s original story Blaze of Glory. Zanuck wanted a picture defined by “guts and realism,” a platform against formula noir pictures that were all too common by the early 1950s. Brown’s treatment was entirely too orthodox for Zanuck, who, according to early conference notes about the film, craved a “hard-hitting Richard Widmark kind of thing.” Who better to communicate that than Samuel Fuller? Having greatly admired Fuller’s intense and genuine war movies like Steel Helmet and Fixed Bayonets, Zanuck entrusted Fuller to create a visceral, truth-telling portrayal of the criminal underworld.

What Fuller might call a “pisscutter-of-a-movie,” Pickup on South Street contains a lurid realism in respect to his cold-blooded, amoral, yet oddly noble central characters, all of whom are criminals. In Fuller’s crackerjack script, a pickpocket named Skip McCoy (Richard Widmark, much to Zanuck’s pleasure) lifts the wallet of an unwitting Communist courier on a subway, a dame called Candy (Jean Peters) being trailed by two FBI agents. Unbeknownst to Skip, her wallet contains microfilm holding a top-secret formula meant for an undisclosed nefarious plot. When Candy tells her handler Joey (Richard Kiley) what happened, he tells her to find the pickpocket, and so she follows a trail of names until she reaches Moe (Thelma Ritter), a lowly necktie saleswoman who also gives up information to cops or anyone paying. However, Moe has already given Skip’s name to the police. Skip finds himself downtown, police Captain Dan Tiger (Murvyn Vye) and FBI men appealing to his patriotism to hand over the microfilm. Skip laughs off their pleas, “Are you waving the flag at me?” A three-time loser, Skip plays it cool under pressure, knowing life imprisonment awaits him if they convict him of theft once more. Unable to prove anything, they let Skip go but keep an eye on his movements. Candy later arrives to hunt for the microfilm at Skip’s home, an abandoned bait shack on the Hudson River. She does her best to seduce it out of Skip in a series of visits, and even begins to fall for him in the process, but he sees right through her game and sends her back to Joey for a bigger payoff. It makes no difference to him what secrets the microfilm holds, even after he learns it belongs to Communist spies.

Knowing the cops are watching him and wanting to keep Skip out of jail, Candy eventually bludgeons him over the head and takes the microfilm to Joey, completely unaware that Skip had kept a frame for insurance. Joey beats Candy to a pulp when he discovers this, but she refuses to relinquish the location of Skip’s hideout. Joey then proceeds to Moe and murders her when she too refuses to divulge information to a Red. And so Skip, forced to recognize Candy’s loving sacrifice and enraged by Moe’s murder, gives up on his pursuit of a high-buck payoff and goes after Joey for revenge, slugs him up and down a busy subway station, recovers the microfilm, and catches the Communist agent under the nose of the authorities. In the final scene, Skip and Candy leave the police station free, though Captain Tiger predicts Skip will find himself in trouble again. Candy replies, “You wanna bet?”

Knowing the cops are watching him and wanting to keep Skip out of jail, Candy eventually bludgeons him over the head and takes the microfilm to Joey, completely unaware that Skip had kept a frame for insurance. Joey beats Candy to a pulp when he discovers this, but she refuses to relinquish the location of Skip’s hideout. Joey then proceeds to Moe and murders her when she too refuses to divulge information to a Red. And so Skip, forced to recognize Candy’s loving sacrifice and enraged by Moe’s murder, gives up on his pursuit of a high-buck payoff and goes after Joey for revenge, slugs him up and down a busy subway station, recovers the microfilm, and catches the Communist agent under the nose of the authorities. In the final scene, Skip and Candy leave the police station free, though Captain Tiger predicts Skip will find himself in trouble again. Candy replies, “You wanna bet?”

Fuller wrote in his autobiography, “All over the world, you’ll find small-time crooks like Skip, Candy, and Moe living on the underbelly of society, struggling to survive with their scams, abiding by their own unwritten code of ethics.” Throughout the picture, it is impossible not to observe that the only characters with ties of any kind are the authorities. Fuller’s protagonists do what they must to get by. Skip lifts wallets on subway trains, Moe sells names along with her men’s accent-wear, and Candy does whatever she can to earn cash for dresses. Fuller resolves that Candy is “too dumb to be a hooker, too dumb to be a mistress.” Though her criminal station remains somewhat undefined, Candy presents the frank obscurity by which these people survive. Unskilled though she may be, her good looks and knowledge of the street are enough to keep her going. Fuller’s underworld inhabitants all subsist according to an unwritten code that frees them of any personal responsibility for their actions, with the understanding that each does their part for themselves and no one else. Moe, for example, sells Skip’s whereabouts to the police; however, Skip does not hold it against her. “She’s gotta eat,” he explains. In a tender moment when Candy asks Skip how he came to be a pickpocket, another director might have exploited Skip’s backstory, softening the tone with a melodramatic response. But Fuller knows that a character like Skip would never unnaturally ruminate about his painful past; he instead writes it that Skip shoves Candy away and shouts furiously, “Don’t ask stupid questions!” And Fuller’s rabble accepts that others like them earn their dollar in their own way, politics notwithstanding. When Candy returns to Skip’s shack for the second time to recover the microfilm, he figures she works for the Reds, even if she remains unaware of it herself. “So you’re a Red, who cares? Your money’s as good as anybody else’s.”

Much was made of Skip McCoy and his politically indefinite dialogue in the screenwriting process thanks to the suspicious eyes of both J. Edgar Hoover and the Production Code Administration (PCA), who called for numerous script revisions. In an anecdote told by Fuller himself, during a lunch between Hoover, Zanuck, and Fuller the FBI director wanted the original line “Don’t wave that goddamn flag at me” removed. Though Zanuck and Fuller conceded to remove the profanity, Zanuck defended the purpose of the line, arguing that it had nothing to do with any projected undercurrents of patriotism in the film or lack thereof, rather it had everything to do with the nature of the character, which Hoover could not control even with his authority—he had no jurisdiction over story. Fuller made most of his PCA concessions on the violence depicted in Pickup on South Street, which despite the director’s artistic compromises still represents some of the most shockingly brutal displays from this era of cinema. Take the scene where Joey throws Candy around—she emerges from a bath wrapped up in a zipped robe, but Joey shakes her about the room, smacking her face and slamming her into furniture, and when she tries to escape, he shoots her. Most impressive is that this takes place all in one shot; it is actually Peters and Kiley, not stunt actors. Originally Fuller wanted to suggest that her robe comes off during the struggle, except even if nothing was shown the implication was too much for the PCA. Later, when Skip confronts Joey in the subway station, the sequence, shot from a high angle to capture the fight in all its rowdy glory, blazes with natural-looking but meticulously choreographed violence. Or when Skip first finds Candy rummaging through his shack in the dark, he socks her in the jaw, and when the light come on, that he punched a woman makes no difference to him; he pours beer on her face to wake her up and cackles about it.

Much was made of Skip McCoy and his politically indefinite dialogue in the screenwriting process thanks to the suspicious eyes of both J. Edgar Hoover and the Production Code Administration (PCA), who called for numerous script revisions. In an anecdote told by Fuller himself, during a lunch between Hoover, Zanuck, and Fuller the FBI director wanted the original line “Don’t wave that goddamn flag at me” removed. Though Zanuck and Fuller conceded to remove the profanity, Zanuck defended the purpose of the line, arguing that it had nothing to do with any projected undercurrents of patriotism in the film or lack thereof, rather it had everything to do with the nature of the character, which Hoover could not control even with his authority—he had no jurisdiction over story. Fuller made most of his PCA concessions on the violence depicted in Pickup on South Street, which despite the director’s artistic compromises still represents some of the most shockingly brutal displays from this era of cinema. Take the scene where Joey throws Candy around—she emerges from a bath wrapped up in a zipped robe, but Joey shakes her about the room, smacking her face and slamming her into furniture, and when she tries to escape, he shoots her. Most impressive is that this takes place all in one shot; it is actually Peters and Kiley, not stunt actors. Originally Fuller wanted to suggest that her robe comes off during the struggle, except even if nothing was shown the implication was too much for the PCA. Later, when Skip confronts Joey in the subway station, the sequence, shot from a high angle to capture the fight in all its rowdy glory, blazes with natural-looking but meticulously choreographed violence. Or when Skip first finds Candy rummaging through his shack in the dark, he socks her in the jaw, and when the light come on, that he punched a woman makes no difference to him; he pours beer on her face to wake her up and cackles about it.

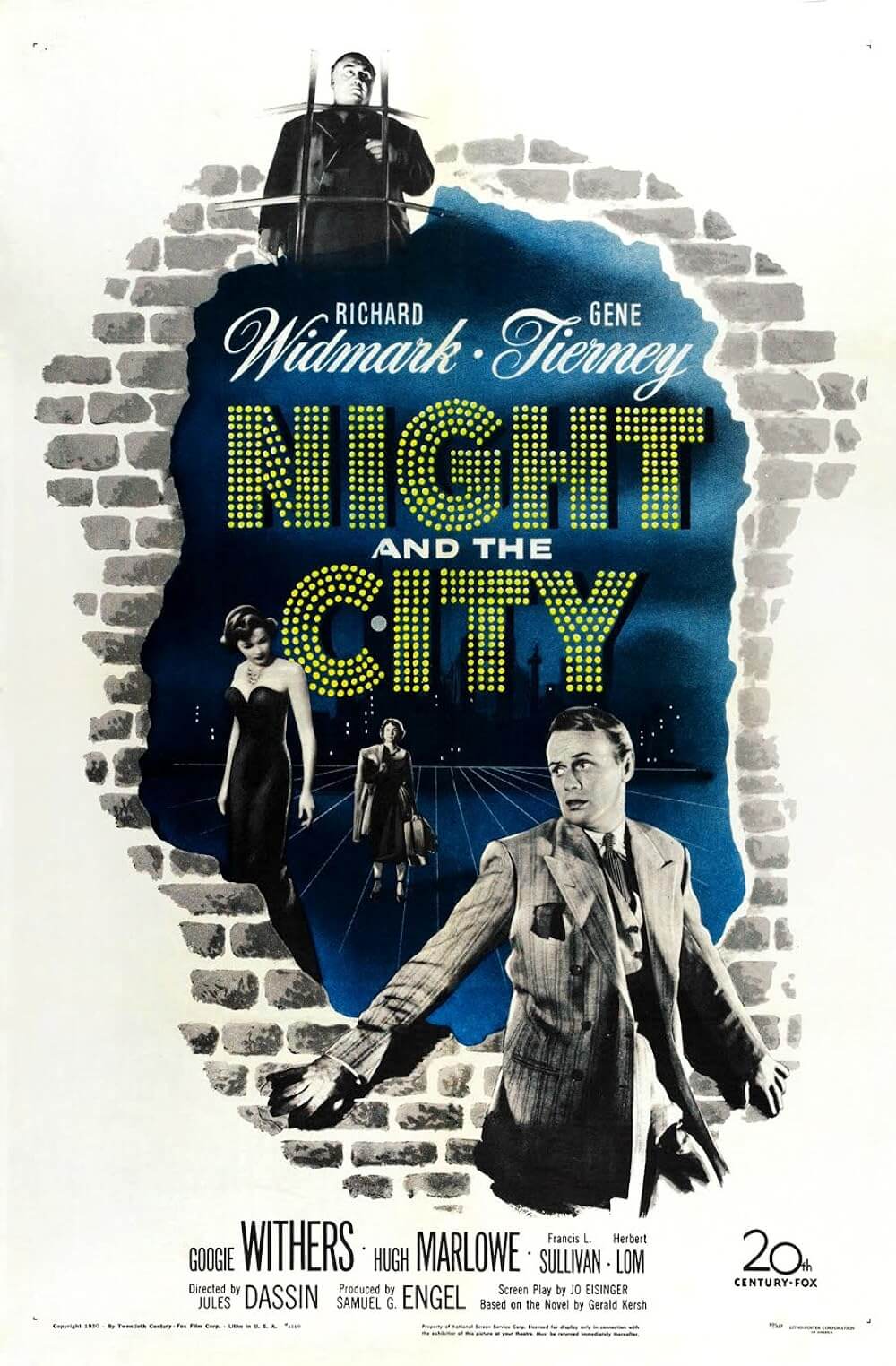

Skip’s coarseness comes easily for Richard Widmark, whose onscreen persona resides beneath the beady eyes and cocky grin of a hard case. Widmark embodies Skip completely, imbuing that same roguish impetuousness he maintains in film noirs like Kiss of Death and Night and the City. A manner of violence booms all around Skip, communicated through Widmark’s body language, the arrogance in the actor’s walk, the way his lips curl when he flashes that seedy smile. Though these expressions resist being warm and welcoming, Fuller’s audience knows the character from their first glimpse—a scoundrel who demands our empathy by admiration of his singular roguish mannerisms. That Widmark’s very presence exudes unnerving tumult helps further the description of Fuller’s setting as a criminal world wrought by violence and urban survivalists.

No character better demonstrates Fuller’s understanding for the need to survive than Moe, as told through Thelma Ritter’s heartfelt, Oscar-nominated performance. Taking cash for neckties and names, she saves to feed her “kitty”—code for a cemetery plot on Long Island. “I have to go on making a livin’ so I can die,” says Moe, afraid of being another nameless corpse dumped onto Potter’s Field, as she does not yet have enough money to reserve her burial plot. When Joey pays her a visit to extract information, resignedly, she becomes aware that her lifetime’s worth of scraping by was in vain. “You’d be doin’ me a big favor if you’d blow my head off,” Moe tells Joey. And he does. After Skip learns of her murder, Fuller shows him stopping the ferry carrying numbered coffins to Potter’s Field and taking Moe’s body to be buried with dignity, and in that reveals the character’s compassion. Fuller’s means to point out the travesty of a world that demands people spend their lives saving for death. But this world is where Fuller grew up. In a physical sense, his descriptions of New York City, although filmed on a Hollywood studio, bear staggering verisimilitude. Cinematographer Joe MacDonald (My Darling Clementine) uses noirish lighting and finds impressive detail embedded into the film’s few sets, creating a sense of haphazard “realism” like that employed by early Italian Neorealists such as Vittorio De Sica, Roberto Rossellini, and Luchino Visconti. Embedded into this cityscape are ripe characters taken from real life, each given an unmatched power developed from the director’s personal experience on the streets of New York.

No character better demonstrates Fuller’s understanding for the need to survive than Moe, as told through Thelma Ritter’s heartfelt, Oscar-nominated performance. Taking cash for neckties and names, she saves to feed her “kitty”—code for a cemetery plot on Long Island. “I have to go on making a livin’ so I can die,” says Moe, afraid of being another nameless corpse dumped onto Potter’s Field, as she does not yet have enough money to reserve her burial plot. When Joey pays her a visit to extract information, resignedly, she becomes aware that her lifetime’s worth of scraping by was in vain. “You’d be doin’ me a big favor if you’d blow my head off,” Moe tells Joey. And he does. After Skip learns of her murder, Fuller shows him stopping the ferry carrying numbered coffins to Potter’s Field and taking Moe’s body to be buried with dignity, and in that reveals the character’s compassion. Fuller’s means to point out the travesty of a world that demands people spend their lives saving for death. But this world is where Fuller grew up. In a physical sense, his descriptions of New York City, although filmed on a Hollywood studio, bear staggering verisimilitude. Cinematographer Joe MacDonald (My Darling Clementine) uses noirish lighting and finds impressive detail embedded into the film’s few sets, creating a sense of haphazard “realism” like that employed by early Italian Neorealists such as Vittorio De Sica, Roberto Rossellini, and Luchino Visconti. Embedded into this cityscape are ripe characters taken from real life, each given an unmatched power developed from the director’s personal experience on the streets of New York.

In his early teens, Fuller became a copy boy and found his kinship with ink and words. By seventeen he was reporting crimes from the underworld to readers of a prickly tabloid, the New York Evening Graphic. At this young age he played witness to bloody murder scenes, all manner of crimes, scandal, and corruption amid officialdom, all of which would serve as inspiration later on. Once his paper shut down, he reformatted what he had seen into pulpy yarns, selling short novels and the occasional (sometimes ghostwritten) script to Hollywood. His first script sold in 1936 when he was just 24. When he returned from his duties as an infantryman in WWII, where he helped liberate the German concentration camp at Falkenau, Fuller began working for Hollywood full-time. And in 1949 he directed his debut feature, a vital Western called I Shot Jesse James.

Over the next several decades, Fuller’s filmmaking style earned him a reputation for confronting the viewer with energetic camerawork and emotionally wrenching storylines. Strangely and often miraculously, Fuller’s films found balance between their barefaced audacity and their dramatic resonance. Consider The Naked Kiss, his colorful humanization of prostitution, which begins with a shaved-headed Constance Towers attacking a first-person perspective camera angle doubling as her pimp. Forty Guns features Barbara Stanwyck as a rancher protected by a small army of hired guns; she rides on horseback around her expanse of land, an army of male soldiers, thin metaphors for phalluses, following behind her. Or take White Dog, his 1982 film that was blacklisted by Paramount Pictures and labeled racist. In it, a dog trained to attack black people serves as an allegory for the inhumanity of racism—the film’s critics clearly missed the point, as they often do with Fuller’s work. Though many of his films were unfortunately labeled B-movies—as if budgets and big-name stars could ever determine the quality of a motion picture—Fuller’s output has its admirers among scholars and directors. Martin Scorsese and Wim Wenders have done their part to help stimulate awareness about Fuller’s career through written appreciations or references to Fuller in their films visually, thematically, or just placing him in the cast. Jean-Luc Godard asked Fuller to appear in his 1965 film Pierrot le fou—Fuller appears in sunglasses, standing against a wall, playing a beatnik version of himself. As the tale goes, Godard asked Fuller to improvise a definition for film with the camera. Fuller responded, “Film is like a battleground. Love. Hate. Action. Violence. Death. In one word . . . emotion.” This adlib is often used to describe Fuller’s aesthetic approach.

Over the next several decades, Fuller’s filmmaking style earned him a reputation for confronting the viewer with energetic camerawork and emotionally wrenching storylines. Strangely and often miraculously, Fuller’s films found balance between their barefaced audacity and their dramatic resonance. Consider The Naked Kiss, his colorful humanization of prostitution, which begins with a shaved-headed Constance Towers attacking a first-person perspective camera angle doubling as her pimp. Forty Guns features Barbara Stanwyck as a rancher protected by a small army of hired guns; she rides on horseback around her expanse of land, an army of male soldiers, thin metaphors for phalluses, following behind her. Or take White Dog, his 1982 film that was blacklisted by Paramount Pictures and labeled racist. In it, a dog trained to attack black people serves as an allegory for the inhumanity of racism—the film’s critics clearly missed the point, as they often do with Fuller’s work. Though many of his films were unfortunately labeled B-movies—as if budgets and big-name stars could ever determine the quality of a motion picture—Fuller’s output has its admirers among scholars and directors. Martin Scorsese and Wim Wenders have done their part to help stimulate awareness about Fuller’s career through written appreciations or references to Fuller in their films visually, thematically, or just placing him in the cast. Jean-Luc Godard asked Fuller to appear in his 1965 film Pierrot le fou—Fuller appears in sunglasses, standing against a wall, playing a beatnik version of himself. As the tale goes, Godard asked Fuller to improvise a definition for film with the camera. Fuller responded, “Film is like a battleground. Love. Hate. Action. Violence. Death. In one word . . . emotion.” This adlib is often used to describe Fuller’s aesthetic approach.

Fuller sought to wake his audience up with blows to the gut and harsh slaps to the face. To call his work blunt would be an understatement, but he never resorts to superficial shocks. His films are at once honest and daring, ballsy and genuine, and always filled with characters contradictory by design. With scripts pulled tight as a hanging rope, his objective is truth. If that means he has to communicate through amplification or sacrifice good taste, so be it—humanity rarely behaves in good taste, which Fuller had witnessed more than most, so his films illustrate that trend with unflinching candor. Perhaps this is why Fuller remains best known for his authentic war pictures. Having seen how soldiers behave first hand, he knew those John Wayne actioners about the glories of battle were hogwash romanticized for the American viewer. Battle was brutal and unromantic. Fuller’s war pictures, most significantly The Big Red One and Steel Helmet, show how wartime has very little to do with heroes, rather just unfortunate people who endure a turbulent landscape and somehow survive. Pickup on South Street is the same. Take a Fuller war picture, diminish the scope to a cold war setting, point the camera into back alleys and sordid parts of the urban backdrop, and the films carry identical themes about desperation and survival at any cost.

When Pickup on South Street was released in 1953 during an era where the cold war climate put an eerie chill over the United States, Fuller’s film jabbed at this absurd paranoia by representing characters whose motivations were more basic, more insignificant than politics or borders or top-secret formulas. Critics, however, interpreted the picture according to their own views. That the film refused to make an oblique, outspoken political commentary and yet concerned itself with an otherwise hot cold war topic earned it diverse readings. Some believed it a pro-communist, anti-American assessment. Others called it a welcomed anti-communist critique. Fuller insisted his film was just a story and only that: “My yarn is a noir thriller about marginal people, nothing more, nothing less.” By avoiding political statements in Pickup on South Street and releasing a film about people without labels, Fuller sends a powerful message to those driving cold war obsessions or overtly political moviemaking. The director’s intentional lack of perceptible biased offers an individualist alternative to the grand stakes of a traditional studio film, thus he rebels against an era desperate to propagate its jealous Americanism. Standing on unpatriotic and certainly criminal grounds, the film sustains grit, intelligence, sincerity, yet still entertains in a way that challenges the viewer with ideas of humanism. Through this narrative about hoods just trying to survive, the picture permeates raw, volatile emotion onto the screen, fully characterizing the elemental energy of Samuel Fuller’s cinema.

When Pickup on South Street was released in 1953 during an era where the cold war climate put an eerie chill over the United States, Fuller’s film jabbed at this absurd paranoia by representing characters whose motivations were more basic, more insignificant than politics or borders or top-secret formulas. Critics, however, interpreted the picture according to their own views. That the film refused to make an oblique, outspoken political commentary and yet concerned itself with an otherwise hot cold war topic earned it diverse readings. Some believed it a pro-communist, anti-American assessment. Others called it a welcomed anti-communist critique. Fuller insisted his film was just a story and only that: “My yarn is a noir thriller about marginal people, nothing more, nothing less.” By avoiding political statements in Pickup on South Street and releasing a film about people without labels, Fuller sends a powerful message to those driving cold war obsessions or overtly political moviemaking. The director’s intentional lack of perceptible biased offers an individualist alternative to the grand stakes of a traditional studio film, thus he rebels against an era desperate to propagate its jealous Americanism. Standing on unpatriotic and certainly criminal grounds, the film sustains grit, intelligence, sincerity, yet still entertains in a way that challenges the viewer with ideas of humanism. Through this narrative about hoods just trying to survive, the picture permeates raw, volatile emotion onto the screen, fully characterizing the elemental energy of Samuel Fuller’s cinema.

Bibliography:

Dombrowski, Lisa. The Films of Samuel Fuller: If You Die, I’ll Kill You! Wesleyan University Press, 2008.

Fuller, Samuel; Fuller, Christa Lang; Rudes, Jerome Henry. A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting and Filmmaking.New York: Knopf, 2002.

Mosley, Leonard. Zanuck: The Rise and Fall of Hollywood’s Last Tycoon. Boston: Little, Brown, c1984.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. New York: Pantheon, 1988.

Scorsese, Martin; Henry, Michael. A Personal Journey Through American Movies. New York: Hyperion, 1997.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review