The Definitives

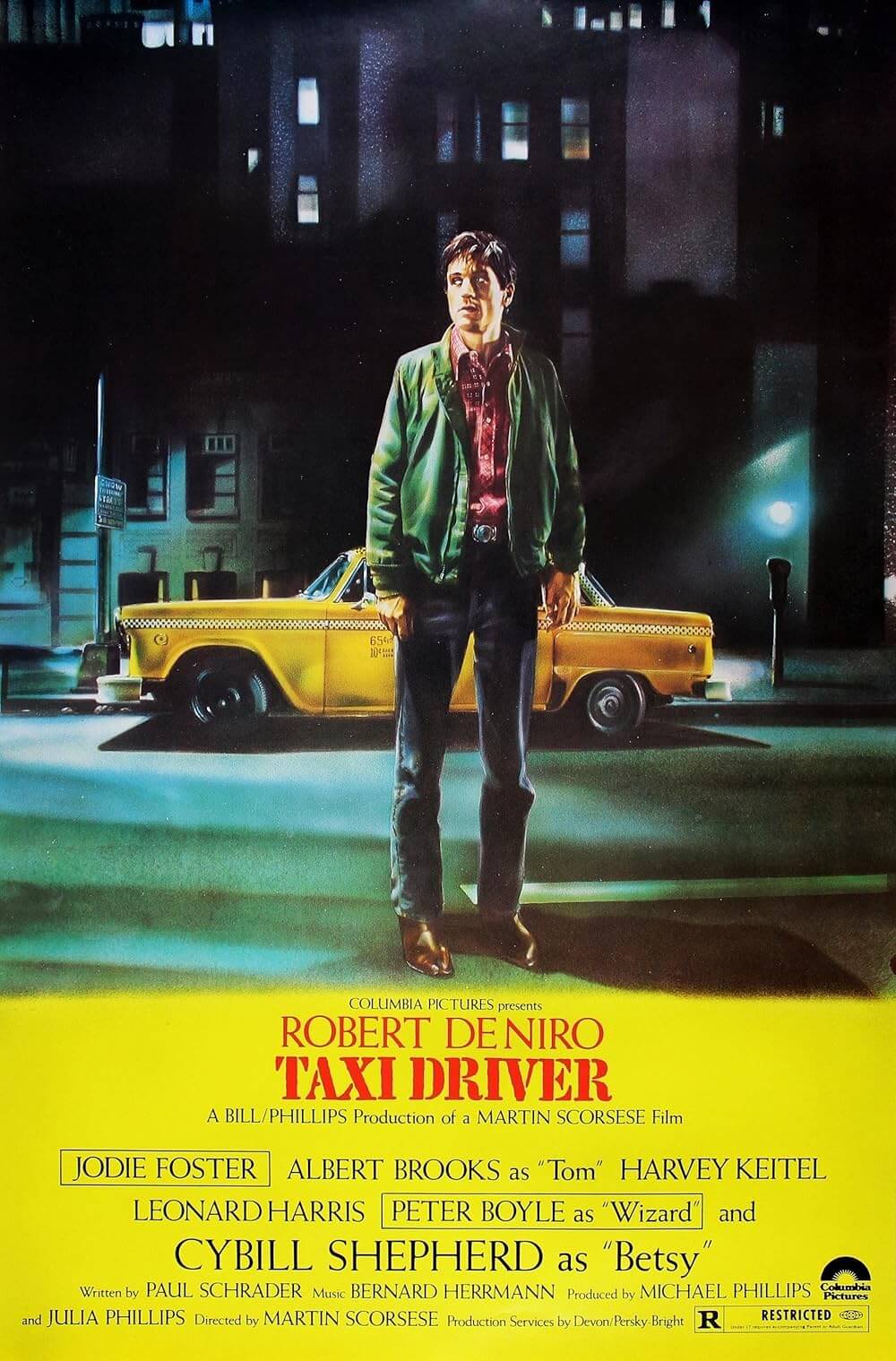

Taxi Driver

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Much has been put forward about Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and its meaning. Travis Bickle, Robert De Niro’s loner New York City cabbie, has been called an attack on the failed deliverance promised by the 1960s, as boiled down into one man’s troubled psyche. Others see the film as a warning to society at large personified by Bickle, who was inspired by Alabama Governor George Wallace’s would-be assassin Arthur Bremer, to not cast away those who might be psychopaths less it becomes too late. Bickle has been seen as a religious avenger singularly compelled by his sexual repression and violent impulses. Freudian theorists interpret the film’s gun fetishism and the way Bickle fawns over firearms as a response to his castration anxiety. While the film has rarely been misread as a product of racism, Bickle’s apparent hatred toward African-Americans has been described as his desire to reclaim the urban sprawl for the white male. But then again, he might just be a flaneur, wandering a city that drives him to madness.

As theories about the film diverge, each of these readings has its merits, which is certainly why the film endures as a permanent classic. Travis Bickle and thus Scorsese’s film is a blank slate onto which we project our own meaning, making the film strangely and uniquely universal, in spite of the artful treatment and shocking subject matter. People seem to identify with Travis’ status as an outsider, yet within the film, his precise psychopathy remains elusive because Scorsese does not judge or examine his case study with overt detail. We watch aghast as Travis attempts to take a woman to a porno theater on their first date or as he slowly deteriorates into a mohawked political assassin, but then he also seems to display moments of goodness in his desire to rescue a preteen streetwalker. Bickle and the film are as much enigmas as they are overexposed notions in the mind of cinephiles, referenced and replayed enough so that we have their scenes memorized. The film has become so iconic that it’s almost a cliché, but so significant that its enduring power cannot be denied.

Just as Taxi Driver arouses uncertain interpretations, the film itself opens in a haze. Sewer steam billows from below as, in the first shot, a taxicab emerges from out of the fog. This eerie title sequence gives way to Travis, who enters a Checkered Cab dispatch office looking for a job with a mist following behind him, as though he has materialized from nothingness. Most of what we learn about Travis comes forth during his subsequent job interview: he is 26-years-old, he served in the Vietnam War and was honorably discharged in 1973, and his education is sketchy at best. He stands at a distance from the dispatch interviewer who, as most characters do throughout, senses something is wrong. But Travis is willing to drive a cab in the worst neighborhoods, and at any hour, so he gets the job. The scene is from Travis’ perspective, looking down at the dispatcher, as is the majority of the film. As a result, we must watch Travis closely; he is an unreliable narrator lost deep in his own syndrome of paranoia.

Just as Taxi Driver arouses uncertain interpretations, the film itself opens in a haze. Sewer steam billows from below as, in the first shot, a taxicab emerges from out of the fog. This eerie title sequence gives way to Travis, who enters a Checkered Cab dispatch office looking for a job with a mist following behind him, as though he has materialized from nothingness. Most of what we learn about Travis comes forth during his subsequent job interview: he is 26-years-old, he served in the Vietnam War and was honorably discharged in 1973, and his education is sketchy at best. He stands at a distance from the dispatch interviewer who, as most characters do throughout, senses something is wrong. But Travis is willing to drive a cab in the worst neighborhoods, and at any hour, so he gets the job. The scene is from Travis’ perspective, looking down at the dispatcher, as is the majority of the film. As a result, we must watch Travis closely; he is an unreliable narrator lost deep in his own syndrome of paranoia.

The script was born from an ultimate low period in screenwriter Paul Schrader’s life; he had hit rock bottom, was drinking heavily, and he lived in his car in a bout of self-imposed loneliness after relationships with both his wife and girlfriend collapsed. It was during this deprived interlude where Schrader read media coverage on and the diaries of Arthur Bremer, who shot presidential candidate Wallace in 1972 only to leave him paralyzed from the waist down. Schrader found himself understanding, to a degree, how someone in his own state of terminal loneliness could decline into someone like Bremer. From these roots, the script was completed in 10 days, channeling his detached, frustrated, angry mental state into the Bremer-like figure that would be Travis Bickle. While borrowing ideas directly from Bremer for Travis’ construction, he also used filmic sources: John Ford’s The Searchers provided a loose structure in which Travis is akin to John Wayne’s troubled hero Ethan, a war veteran character bearing heavy demons and desperate to rescue a girl who has been violated by a villain. Film noir lent Schrader further insight—just as WWII informed characters in film noir from the 1940s with their cynical worldview, America’s identity-crushing loss in Vietnam would inform Travis, whose seeming postwar shell-shock left him in a state of psychosis.

But, as with much about Travis, we have to question if he ever actually went to Vietnam. His generic army coat could be picked up at any army surplus store, his knowledge of guns is perhaps the result of his extremism, and anyone who watches too many Bruce Lee movies could suddenly jump into his martial arts stance. That we cannot be certain of Travis Bickle or his origins makes him all the more fascinating, and frightening, as what little we learn about him is dissolved by what we see, his personality typical of a narcissistic personality disorder. His interactions with others have strange results; he is all but incapable of making small talk with his fellow cabbies—they know something is wrong him, call him ironic nicknames like “ladies man” and “killer” and laugh, while they also keep a safe distance. Travis is someone to tiptoe around, others realize, as he is borderline: meaning, the wrong conditions (all present in the film) could push him over the edge. And so, when his narration, read staidly from the Bremer-esque diary he keeps, admits “All my life what I needed was a sense of someplace to go,” it becomes a chilly affirmation that Travis is headed toward the film’s inevitable violent outburst.

But, as with much about Travis, we have to question if he ever actually went to Vietnam. His generic army coat could be picked up at any army surplus store, his knowledge of guns is perhaps the result of his extremism, and anyone who watches too many Bruce Lee movies could suddenly jump into his martial arts stance. That we cannot be certain of Travis Bickle or his origins makes him all the more fascinating, and frightening, as what little we learn about him is dissolved by what we see, his personality typical of a narcissistic personality disorder. His interactions with others have strange results; he is all but incapable of making small talk with his fellow cabbies—they know something is wrong him, call him ironic nicknames like “ladies man” and “killer” and laugh, while they also keep a safe distance. Travis is someone to tiptoe around, others realize, as he is borderline: meaning, the wrong conditions (all present in the film) could push him over the edge. And so, when his narration, read staidly from the Bremer-esque diary he keeps, admits “All my life what I needed was a sense of someplace to go,” it becomes a chilly affirmation that Travis is headed toward the film’s inevitable violent outburst.

Schrader’s script was initially given to Brian De Palma to direct, but producers Michael and Julia Phillips chose Scorsese after seeing his stylistic breakthrough Mean Streets (1973). Their decision with Scorsese was hesitant until the director’s next picture, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Any More (1974), which resulted in an Oscar for that film’s star, Ellen Burstyn. Add to this De Niro’s Oscar win on The Godfather Part II and the producers finally convinced Columbia president David Begelman to finance the picture for $1.3 million (it would eventually cost $1.9 million to complete), with its star and director working for next to nothing. Begelman loathed the script for its use of violence, although the prospect of Oscar prestige changed his mind. The production filmed over the summer of 1975, an unusually hot summer where New York’s unemployment and crime rates were at their highest. Locations around Time’s Square were then a haven for hookers, pimps, and sex shops, the perfect breeding ground for Travis’ degree of sexually repressed psychosis that turns violent. In post-production, Scorsese and his editors Tom Rolf and Melvin Shapiro employed jump cuts and abrupt transitions, along with Michael Chapman’s fluid but deceptively sedate camerawork to evoke Travis’ frame of mind, which builds his tension into something horrible that the audience feels coming from the first scenes, even if it remains vague. Days seem to pass in-between cuts, as Travis recounts in his diary the effects of working as a New York cabbie. “All the animals come out at night: whores, skunk pussies, buggers, queens, fairies, dopers, junkies, sick, venal. Someday a real rain will come and wash all this scum off the streets.” The film unfolds with an other-worldly atmosphere as if proceeding from within Travis’ deranged viewpoint.

This tone is interrupted by intentionally “normal” scenes of banal jabber between Tom (Albert Brooks) and Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), two campaign hands employed by presidential candidate Charles Palantine (Leonard Harris). Travis has noticed Betsy and believes her to be an “angel” sitting high above all the scum of the city. After watching her for days—at one point she catches him looking, and he speeds away in his cab—he uses his strange energy to convince her to meet him for coffee and pie. They meet again for a movie, but because of Travis’ lack of basic social understanding, a porno movie is all there is, and Betsy storms out, rejects him and refuses to return his calls. Travis’ sexual identity teems with desire but without any understanding or true intention of following through; he is a sexual powder keg waiting to explode. Perhaps this is what attracts him to guns, and why Freudian theorists argue that Travis’ violence is a response to his castration anxiety, to prove his masculinity through the phallic firearm. Such notions become articulated by the maddened characters in Travis’ world, such as the passenger who is played by Scorsese himself (because the original actor reportedly became ill). A coked-up jealous husband, whose wife is cheating on him with a Black man (he uses the N-word), goes on and on about what a .44 Magnum could do to a woman’s head, or her “pussy.” Scorsese’s passenger repeats “That you should see.”

This tone is interrupted by intentionally “normal” scenes of banal jabber between Tom (Albert Brooks) and Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), two campaign hands employed by presidential candidate Charles Palantine (Leonard Harris). Travis has noticed Betsy and believes her to be an “angel” sitting high above all the scum of the city. After watching her for days—at one point she catches him looking, and he speeds away in his cab—he uses his strange energy to convince her to meet him for coffee and pie. They meet again for a movie, but because of Travis’ lack of basic social understanding, a porno movie is all there is, and Betsy storms out, rejects him and refuses to return his calls. Travis’ sexual identity teems with desire but without any understanding or true intention of following through; he is a sexual powder keg waiting to explode. Perhaps this is what attracts him to guns, and why Freudian theorists argue that Travis’ violence is a response to his castration anxiety, to prove his masculinity through the phallic firearm. Such notions become articulated by the maddened characters in Travis’ world, such as the passenger who is played by Scorsese himself (because the original actor reportedly became ill). A coked-up jealous husband, whose wife is cheating on him with a Black man (he uses the N-word), goes on and on about what a .44 Magnum could do to a woman’s head, or her “pussy.” Scorsese’s passenger repeats “That you should see.”

Later, after Travis buys his own .44 Magnum, it becomes clear that Scorsese’s mad passenger was merely a concentrated version of our protagonist, who harbors deep-seated prejudices. As Travis makes his way down the street or takes breaks with his fellow drivers, the camera looms on Black people. Travis’s racism—held in his long, almost catatonic stares of suspicion—comes through in Scorsese’s lingering camera. However, to avoid being judged as a racist film, Scorsese made concessions, such as casting Harvey Keitel as a pimp, although Scorsese and Schrader searched but found only Black pimps in the area where they were filming. Moreover, Scorsese’s endeavors to develop the mise-en-scène as though the entire film takes place through Travis’ eyes, which in turn conveys that the filmmakers themselves were not racist, only their character. Watch the scene where Travis shoots down a Black man robbing a grocery store; the camera looks down on the victim dead on the floor from Travis’ point of view, as Travis steps on the man’s arm and regards him with disgust.

The idea to purchase a gun arises when a fellow cabbie asks him “Do you carry a gun?” He does not, but now that the idea is planted, maybe he should. He buys a stack of weapons from a shady dealer, after which De Niro showcases one of the most recognizable scenes in all of cinema. Schrader famously wrote only “Travis talks to himself in the mirror” in the script, and De Niro even more famously improvised the “You talkin’ to me?” sequence that followed, borrowing the routine from local stand-up comic’s act. Scorsese shoots the scene with heavy symbolism, evoking how Travis has indeed split between the image he has of himself in the mirror—what Scorsese calls, an “avenging angel”—and his real Self that has lost touch. After the grocery store shooting, we are alerted to the fact that Travis’ mirror posturing is backed up by his willingness to shoot someone down, and with his sudden attention to Palantine, the audience grows alarmed. He begins preparing, exercising because “every muscle must be tight” for some yet-unknown mission. Avoiding a streamlined digression, the editing embeds scenes where Travis shows evidence that his existence is not merely sheer lunacy, that when he is around others, he can be almost “normal.” He tells the cabbie Wizard (Peter Boyle) that he has bad ideas in his head and just wants to really do something. Wizard, who senses something is really wrong, tells him “You’re all right killer. Just relax.” But it is Travis’ self-imposed loneliness that fuels his impulses, and in a city like New York, Travis will likely never feel anything but alone.

The idea to purchase a gun arises when a fellow cabbie asks him “Do you carry a gun?” He does not, but now that the idea is planted, maybe he should. He buys a stack of weapons from a shady dealer, after which De Niro showcases one of the most recognizable scenes in all of cinema. Schrader famously wrote only “Travis talks to himself in the mirror” in the script, and De Niro even more famously improvised the “You talkin’ to me?” sequence that followed, borrowing the routine from local stand-up comic’s act. Scorsese shoots the scene with heavy symbolism, evoking how Travis has indeed split between the image he has of himself in the mirror—what Scorsese calls, an “avenging angel”—and his real Self that has lost touch. After the grocery store shooting, we are alerted to the fact that Travis’ mirror posturing is backed up by his willingness to shoot someone down, and with his sudden attention to Palantine, the audience grows alarmed. He begins preparing, exercising because “every muscle must be tight” for some yet-unknown mission. Avoiding a streamlined digression, the editing embeds scenes where Travis shows evidence that his existence is not merely sheer lunacy, that when he is around others, he can be almost “normal.” He tells the cabbie Wizard (Peter Boyle) that he has bad ideas in his head and just wants to really do something. Wizard, who senses something is really wrong, tells him “You’re all right killer. Just relax.” But it is Travis’ self-imposed loneliness that fuels his impulses, and in a city like New York, Travis will likely never feel anything but alone.

What makes Travis compelling and more than just a psychopath is the allusion that part of him wants to do good. We see this in his obsession with Iris (Jodie Foster), a 12-year-old prostitute whom Travis has noticed walking the street. One night, she attempts to get into Travis’ cab to get away. “Just drive,” she tells him, but Travis is frozen, as he often becomes when at all confronted. Quickly, Iris’ pimp, Sport (Keitel), gathers her from the cab and drops a crumpled $20 bill on the cab’s front passenger seat to forget the incident. Travis refuses to even touch the bill; it is tainted by the scum of the city. Rescuing Iris becomes Travis’ noble, albeit selfish quest; he does this because he wants to view himself as a hero (an “avenging angel”). But this rescue attempt is an idea that Travis forces on Iris; after all, despite being degraded and used, Iris almost seems content in her “relationship” with Sport. She even waves off her escape attempt as a bad reaction to being high. When she and Travis meet, she realizes that Travis genuinely wants to help her, and she is thankful, but also she explains that she never asked to be rescued (at least not sober) and has run away from home. For Travis, he recognizes that Sport is a predator who has victimized Iris and brainwashed her, and since no one else will, Travis must rescue her. To an extent, Sport’s brainwashing of Iris is undoubtedly true, but when Travis asks Iris if she wants to be rescued, she inevitably turns him down. It is Travis who wants to rescue her, and he who projects his hatred for the city onto Sport.

Earlier in the film, Palantine and two aides find themselves without a limousine and make the mistake of stepping into Travis’ cab. Their driver engages in small talk about being an avid supporter of the politician but then loses himself in a tirade about cleaning up the city. Travis rants, “I think someone should just take this city and just… just flush it down the fucking toilet.” The passengers realize their cabbie is not well and remain polite; Palantine even shakes Travis’ hand. Travis smiles with the same false grin that he gives the Secret Service agent later at a Palantine rally, the same smile he gave the dispatcher in the first scene. It is Travis’ rather transparent false front. After Iris rejects his proposition of rescue, Travis begins to boil over. A sequence of incidents compiles into a frightening growth of rage: Travis sees Iris with a John; he sees Palantine on TV; he sees a man burst into an uncontrollable rage on the street, mirroring his own inner state. All at once, Travis has shaved his hair into a mohawk, as members of the Special Forces had done in Vietnam to get them into “killer mode.” He arrives at a Palantine rally, armed to the teeth, ready to unleash his mounting tensions into a single gunshot, but he is spotted by Secret Service men and chased into the crowd. Escaping, but still on the brink, Travis redirects his energies to saving Iris, whether she wants to be rescued or not.

Earlier in the film, Palantine and two aides find themselves without a limousine and make the mistake of stepping into Travis’ cab. Their driver engages in small talk about being an avid supporter of the politician but then loses himself in a tirade about cleaning up the city. Travis rants, “I think someone should just take this city and just… just flush it down the fucking toilet.” The passengers realize their cabbie is not well and remain polite; Palantine even shakes Travis’ hand. Travis smiles with the same false grin that he gives the Secret Service agent later at a Palantine rally, the same smile he gave the dispatcher in the first scene. It is Travis’ rather transparent false front. After Iris rejects his proposition of rescue, Travis begins to boil over. A sequence of incidents compiles into a frightening growth of rage: Travis sees Iris with a John; he sees Palantine on TV; he sees a man burst into an uncontrollable rage on the street, mirroring his own inner state. All at once, Travis has shaved his hair into a mohawk, as members of the Special Forces had done in Vietnam to get them into “killer mode.” He arrives at a Palantine rally, armed to the teeth, ready to unleash his mounting tensions into a single gunshot, but he is spotted by Secret Service men and chased into the crowd. Escaping, but still on the brink, Travis redirects his energies to saving Iris, whether she wants to be rescued or not.

Scorsese compares the climax to a wash in purifying blood, where Travis cleanses himself by shedding the blood of the city’s scum to achieve a glorious victory for himself. In a graphic display of violence uncommon in 1970s cinema at that point, Travis shoots down Sport and the other men using Iris, and then makes his way to rescue Iris in a bloody fray of bullets. After the gunfire has settled, Travis is out of ammunition; he puts his gun against his head and pulls the trigger multiple times, the hammer clicking empty. When the police arrive, he pantomimes a gun with his hand and places it again his head, making the sound of gunfire from deep in his throat. It is as though this gunshot has cleaned out Travis’ mind and exorcised, albeit temporarily, his extremism. In Bremer’s unpublished diary A Cretique [sic] of My Life, he expressed his desire to become more organized, something to which Travis also aspires. He mentions it to Besty on their first encounter, quipping “I should get one of those signs that says ‘One of these days I’m gonna get organezized.’” Getting his mind “organized” through a violent purification aligns with Scorsese’s insistence that Travis sees himself as a religiously justified figure who cleans up New York City’s streets, although the evidence for this interpretation in the film is lacking. Never does Travis attend church or convey any interest in religion. But not knowing what precisely drives him is what makes Travis and the film so compelling.

To avoid an X-rating because of the bloodshed in the shootout sequence, Scorsese printed the film in a way so the blood looks less red, rather grainy and artificial. As a result, the R-rated sequence plays like Travis’ reverie-come-true and seems to exist in an other-worldly dream state. Afterward, when a letter from Iris’ parents and images of newspaper clippings call Travis a vigilante hero, one must wonder if Travis is really purified or if this cycle will start all over again. The final scene shows Betsy getting into Travis’ cab. She clearly wants to reconnect—if there ever was a connection at all—with Travis after his fifteen minutes of fame, but he plays noble and resists her. As he pulls away, in the last moment Travis looks back at Besty in the rearview mirror with a paranoid gaze. Some have interpreted the final scene as a happy ending that suggests Travis’ head has finally been “organized”; this is the appraisal that Scorsese prefers. Still, one gets the inkling that the film’s climax has but provisionally cleansed Travis’ cluttered mind and that already his head is becoming entangled once more. Then again, others still believe everything that occurs after the shootout is a fantasy reeling in Travis’ head, his character either near death or finally lost in his own fantasy. The uncertainty of this sequence has haunted viewers since the film’s debut.

To avoid an X-rating because of the bloodshed in the shootout sequence, Scorsese printed the film in a way so the blood looks less red, rather grainy and artificial. As a result, the R-rated sequence plays like Travis’ reverie-come-true and seems to exist in an other-worldly dream state. Afterward, when a letter from Iris’ parents and images of newspaper clippings call Travis a vigilante hero, one must wonder if Travis is really purified or if this cycle will start all over again. The final scene shows Betsy getting into Travis’ cab. She clearly wants to reconnect—if there ever was a connection at all—with Travis after his fifteen minutes of fame, but he plays noble and resists her. As he pulls away, in the last moment Travis looks back at Besty in the rearview mirror with a paranoid gaze. Some have interpreted the final scene as a happy ending that suggests Travis’ head has finally been “organized”; this is the appraisal that Scorsese prefers. Still, one gets the inkling that the film’s climax has but provisionally cleansed Travis’ cluttered mind and that already his head is becoming entangled once more. Then again, others still believe everything that occurs after the shootout is a fantasy reeling in Travis’ head, his character either near death or finally lost in his own fantasy. The uncertainty of this sequence has haunted viewers since the film’s debut.

Upon its release, Taxi Driver opened to positive box-office numbers (earning roughly $29 million) and critical response, with only a handful of particularly heated assessments attacking the film for its violence and liberal stance on the post-Vietnam War downturn of America. Mainstream Hollywood also favored a less cynical film at the subsequent Academy Awards ceremony, where, despite being nominated for four Oscars (Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actress, and Bernard Herrmann for Best Score), Taxi Driver lost to the inspirational boxing movie Rocky. Note that Scorsese did not receive a nomination. The crowd at the Cannes Film Festival was more receptive to the film’s ambiguous nature, as they often are, and awarded it the Palme d’Or. The enduring careers of both Scorsese and De Niro would bring audiences back to the film over the years, and today it is considered among the most important films of the 1970s.

Events since the film’s release have tagged it with a regrettable, yet undeniable stigma and degree of fascination: just as Arthur Bremer’s attempt to kill George Wallace inspired Schrader to conceive of Travis Bickle, Taxi Driver, in turn, inspired John Hinkley to make his own attempt against Ronald Reagan in 1981. Hinkley blamed the film for his own psychosis, which included an obsession with Jodie Foster, whom he followed to Yale University and subsequently stalked until his assassination attempt—an act designed to impress Foster. His blame toward the film was enough a part of his defense’s argument that the jury in Hinkley’s case was asked to watch Taxi Driver, which Hinkley claimed to have seen 15 times and said drove him to madness. After the incident, Scorsese considered retiring as a director, but instead made The King of Comedy (1983), another picture in which De Niro plays a fanatical character obsessed with someone famous, but with decidedly less disturbing results.

Events since the film’s release have tagged it with a regrettable, yet undeniable stigma and degree of fascination: just as Arthur Bremer’s attempt to kill George Wallace inspired Schrader to conceive of Travis Bickle, Taxi Driver, in turn, inspired John Hinkley to make his own attempt against Ronald Reagan in 1981. Hinkley blamed the film for his own psychosis, which included an obsession with Jodie Foster, whom he followed to Yale University and subsequently stalked until his assassination attempt—an act designed to impress Foster. His blame toward the film was enough a part of his defense’s argument that the jury in Hinkley’s case was asked to watch Taxi Driver, which Hinkley claimed to have seen 15 times and said drove him to madness. After the incident, Scorsese considered retiring as a director, but instead made The King of Comedy (1983), another picture in which De Niro plays a fanatical character obsessed with someone famous, but with decidedly less disturbing results.

Hinkley is the perfect example of how Taxi Driver imposes an infectious relationship with its viewer, as the film’s elusive quality festers within us and creates a need to revisit the film again and again. When we come back to the film, we discover all new details that perhaps went unnoticed before, some of them intentionally embedded by the filmmakers, others not. That which we know about what occurs in the film is vast, but that which we do not know is even greater. Even Scorsese and Schrader cannot agree as to what their film is “about.” In turn, film scholars and cinephiles have continuously reevaluated the film only to diverge in their many varied interpretations. Watching it again and even recounting the story in relative depth, there is much about Scorsese’s picture that remains a mystery. But just enough about Taxi Driver is known and maintained within the consciousness of popular film culture that we keep returning to it in hopes of figuring it out, but more importantly figuring out what it means to us. It is that urgency to revisit the film which makes it an enduring and necessary piece of film history.

Bibliography:

Christie, Ian; Thompson, David (edited by). Scorsese on Scorsese. Revised Edition. Faber, 2003.

Scorsese, Martin; Henry, Michael. A Personal Journey Through American Movies. Hyperion, 1997.

Taubin, Amy. Taxi Driver. British Film Institute Modern Classics, BFI Publishing, 2000.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review