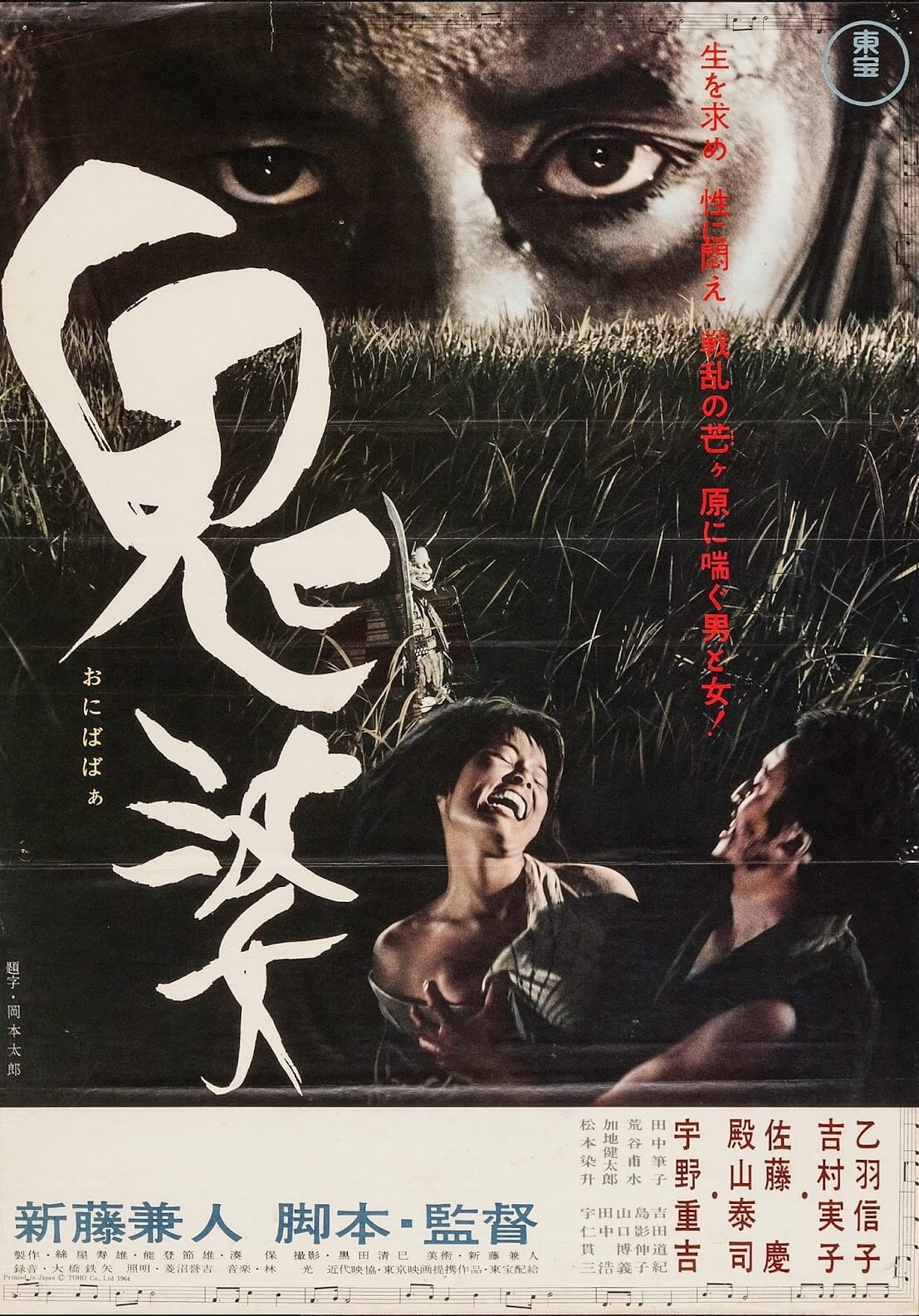

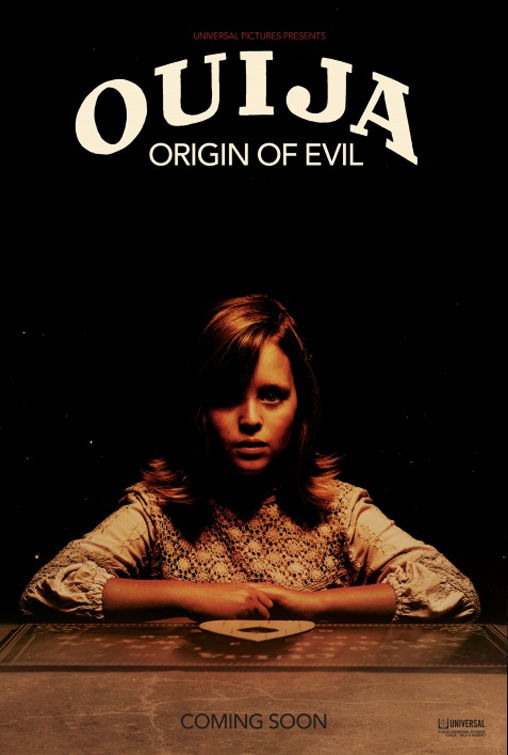

Ouija: Origin of Evil

By Brian Eggert |

Ouija: Origin of Evil exists because of its predecessor, Universal’s Ouija, which earned over $100 million in worldwide receipts on a next-to-nothing budget. The prequel, made for a meager $9 million, opens in wide release around Halloween and will likely earn a hefty profit as well. Except, this time the earnings will be justified, because the result is a far superior horror movie, regardless of being based on a board game. Then again, after my zero-star review of Ouija, it wouldn’t take much to outperform the original disaster-of-a-movie. But director Mike Flanagan crafts an effective and stylish experience whose primary downfall remains its association with the abortive original. Set aside that correlation, and audiences enjoy a skillfully made supernatural yarn best taken on its own terms.

Obliged to expand upon established mythology, Flanagan and his writing partner Jeff Howard set their story in 1965, in the same maligned house as the original. Widow Alice Zander (Elizabeth Reaser) runs a séance scam out of her parlor using trick candles and dramatics—all with the help of her two young daughters, high-schooler Paulina (Annalise Basso) and 9-year-old Doris (Lulu Wilson). When Alice picks up a Ouija board to incorporate into her act using magnets under the table to move the planchette, Doris finds she can use her newly discovered sixth sense to speak to the dead for real. The girl’s first contact with the spirit world is seemingly her late father, who Alice is desperate to speak with again. Paulina remains unconvinced and feels something unnatural is going on, and rightly so: One night, a malignant, oil-slicked spirit (Doug Jones) appears and crawls down Doris’ throat, turning her into a kind of possessed demon seed.

While Flanagan delivers creepy child antics and spooky images that may seem common to fans of franchises like The Conjuring or Insidious, the director heightens the scares with his close attention to character development. There’s a lingering sense of grief beneath these characters, particularly Alice and Paulina, but also the resident priest, Father Tom (Henry Thomas, excellent), a widower who questions his devotion to the priesthood against a potential romance with Alice. Even Paulina’s boyfriend (Parker Mack) seems to have more dimension than your typical horny teen boy role. Indeed, accomplished actors deliver strong performances by imbuing substance into their roles. However, given the movie’s prequel status, the viewer should prepare themselves for its unrelenting treatment of these well-established characters once the tense climax launches in the final twenty minutes.

With a couple of solid genre efforts on his filmography (Absentia, Oculus), Flanagan has an eye for craft beyond what Ouija: Origin of Evil’s teenaged target audience is likely to appreciate. Nevertheless, the production’s visual touches and technical details elevate the otherwise predictable proceedings. For instance, the opening titles have a retro feel that reflects the 1960s setting. And even though cinematographer Michael Fimognari shoots on digital, his lensing looks like grainy film stock of the era, complete with digitally added cigarette burns where the reels would have been switched on an old-fashioned projector. Moreover, using a split-diopter lens effect, Flanagan delivers effective chills in compositions that juxtapose close-ups with unsettling activity in the distant background. Elsewhere, he employs silly looking, wide-mouthed CGI to represent the monstrous version of Doris.

Best of all, Ouija: Origin of Evil makes the most of its PG-13 rating and without an overreliance on empty jump scares and characters who go investigating creaky sounds in the dark. Instead, there’s a disturbing backstory about a Nazi doctor and a performance by Wilson that curdles the blood—most notably in a scene where she describes for Pauline’s boyfriend, in horrifying detail, what it feels like to be strangled to death. Flanagan and Howard construct a tight story driven by their characters’ fears and well-developed emotional history, while the Ouija component, a necessary intellectual property device, remains the weakest element of the movie. In the end, the movie should stand as a shining example to studios that a director with vision and a solid script can turn a nonsensical franchise entry in something worthy of attention.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review