Silence

By Brian Eggert |

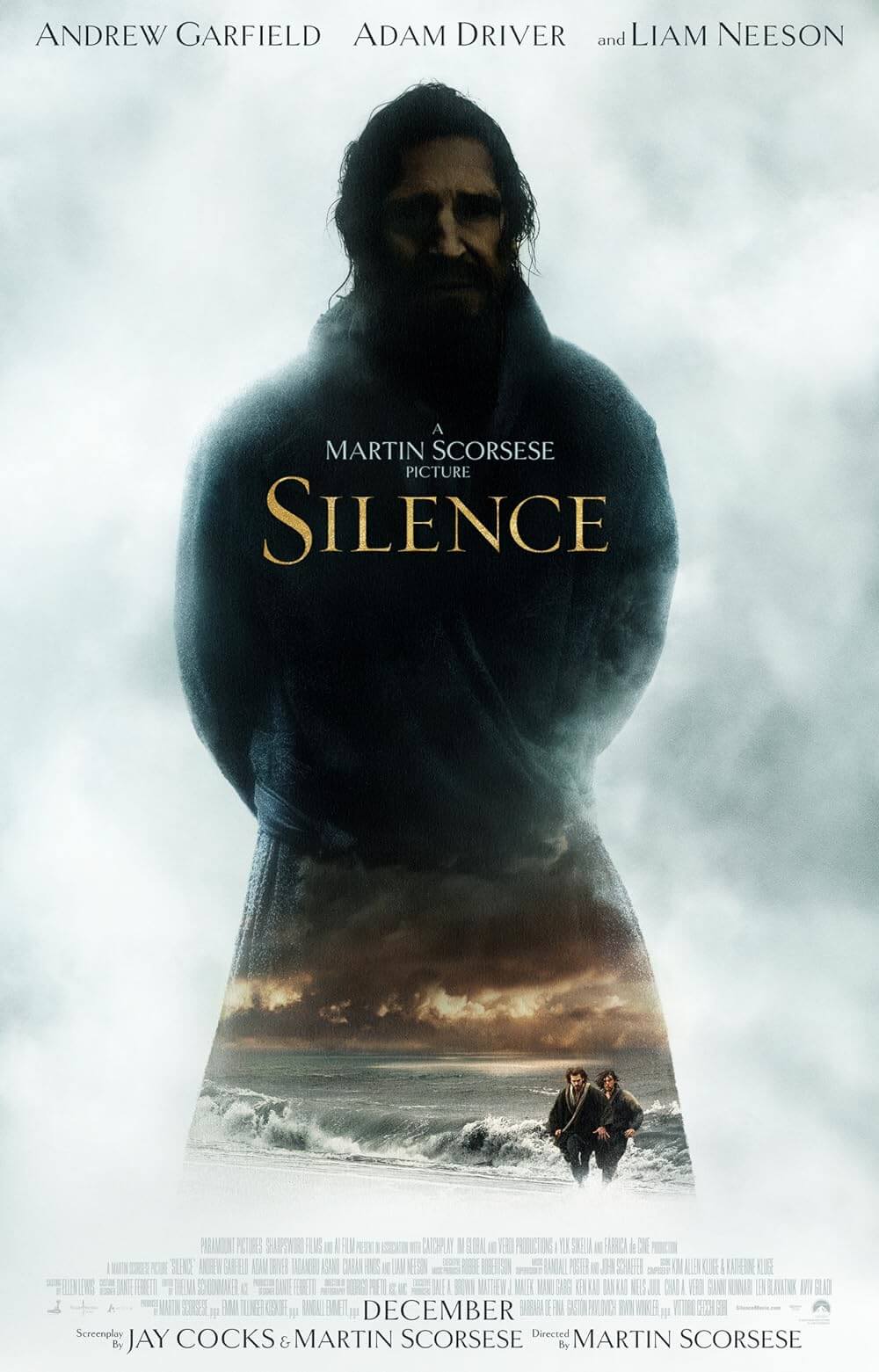

Martin Scorsese meditates on questions of Catholic belief and apostasy in Silence, an adaptation of Japanese author Shusaku Endo’s 1966 novel of the same name. Scorsese’s long-in-development passion project engages religious subject matter without artistic compromise or consideration of the film’s commercial prospects, asking questions about the contradictions of faith within a punishing historical environment. The picture recalls the work of Ingmar Bergman, most notably The Seventh Seal (1957), in which God remains mute in the face of desperate appeals from the protagonist, a Medieval knight. However, the outcome settles on a far less pleasant note, resolving, as one might expect from Scorsese, that suffering breeds understanding. There’s no question that Silence is a profoundly personal film for Scorsese, completing the director’s spiritual trilogy, after The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) and his underappreciated Kundun (1997). And like those films, many will find his latest to be uncommonly restrained, ruminative, and perhaps even impenetrable.

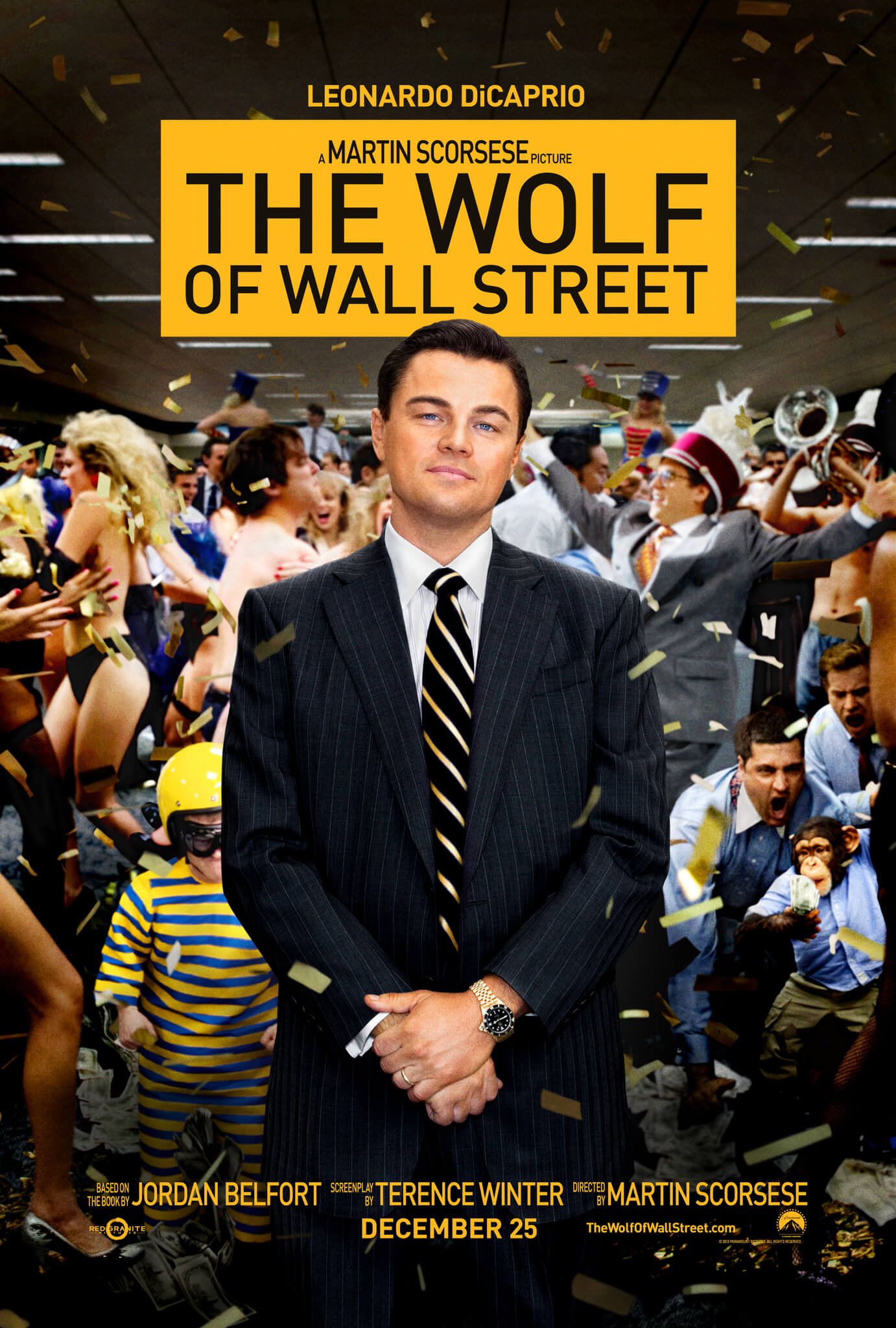

When Scorsese visited Japan to shoot scenes as Vincent Van Gogh in Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams (1990), he had the idea to adapt Endo’s novel, which had been adapted in 1971 by Japanese director Masahiro Shinoda. Scorsese had just released his controversial The Last Temptation of Christ, and the Roman Catholic author’s text must have seemed very familiar, containing many pointedly Catholic themes, which the director had explored in previous features from Mean Streets (1973) onward. After the idea to adapt Silence was born, Scorsese worked alongside scripter Jay Cocks, his writing partner on The Age of Innocence (1993) and Gangs of New York (2002), to realize his version on the screen. It comes as a somewhat ironic revelation that Scorsese finally began production after his last release, the bacchanal dark comedy The Wolf of Wall Street.

Silence takes place in seventeenth-century Japan where signs of Christianity remain after Japanese officials have suddenly banned the religion, despite decades of acceptance. After a religious cleansing in which thousands of Catholics die, so-called Kirishtans linger in rural villages and huts across the Japanese countryside, suffering interrogation and persecution from a local inquisitor named Inoue (Issey Ogata). Among those hunted, Jesuit priests willingly embrace torture by boiling water and crucifixion so they might better identify with Christ. Among them is Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), who goes missing and, according to rumor, has apostatized (renounced Christianity in a public forum by stepping on an image of Jesus or the Madonna) to live a quiet life as a Japanese citizen. When word of Ferreira’s fate reaches the Portuguese colony of Macau, Ferreira’s students Father Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Father Garrpe (Adam Driver) venture into Japan to locate their mentor.

Early on, the priests approach fog-laden shores, and Scorsese seems to evoke Apocalypse Now (1979). Clouds of mist and fog shroud the landscape, where Rodrigues and Garrpe are greeted by farmers who see the Jesuits as living proof that God is listening. Rodrigues insists on pushing forward after Ferreira, the film’s resident Col. Kurtz, and soon welcomes the idea of martyrdom—if only because it might mean that God speaks to him. Indeed, Rodrigues and Garrpe endure no end of desperate living on the Catholic underground, witnessing the hellish interrogation and death of several devoted followers. The worse it gets, the more Rodrigues sees mirage-like visions of Christ before him, painterly images that he seems to draw from his memory. And despite the extreme degree of suffering the Jesuits experience, God remains hushed. Elsewhere, Rodrigues falls prey to his pride and links himself to Christ, complete with his very own Judas in Kichijiro (Yosuke Kubozuka), a peasant who betrays Rodrigues to officials several times over, only to beg for forgiveness. At the same time, Inoue becomes equivalent to Pontius Pilate, an unbending, frustrated official who subjects a willing and prideful Rodrigues to horrific, albeit indirect tortures.

Throughout the proceedings, Scorsese adopts a very Malickian approach by using ponderous voiceovers, mostly read from Rodrigues’ letter correspondences and journals—as opposed to the nonstructural poetic verse in, say, Malick’s The Thin Red Line (1998). The voiceovers convey Rodrigues’ inward thoughts, and he remains troublingly distanced from his Japanese followers, seeing them almost exclusively as Others. And because Scorsese tells the film through Rodrigues’ eyes, Silence treats the Japanese characters much the same; Catholic peasants are like sheep, whereas Inoue is downright monstrous. Eventually, in the final third of the film, the voiceover places the viewer at a distance. Rodrigues’ writings stop with his capture, replaced by those of a Dutch trader, who is barely a character in the screen story, and who documents his observations of Rodrigues’ behavior. With the story no longer being told from Rodrigues’ perspective, the audience struggles to know what he’s thinking. Then again, Scorsese’s artistic gambit is that his character has been established well enough at this point, leaving the audience to make assumptions about Rodrigues’ state of mind.

Throughout the proceedings, Scorsese adopts a very Malickian approach by using ponderous voiceovers, mostly read from Rodrigues’ letter correspondences and journals—as opposed to the nonstructural poetic verse in, say, Malick’s The Thin Red Line (1998). The voiceovers convey Rodrigues’ inward thoughts, and he remains troublingly distanced from his Japanese followers, seeing them almost exclusively as Others. And because Scorsese tells the film through Rodrigues’ eyes, Silence treats the Japanese characters much the same; Catholic peasants are like sheep, whereas Inoue is downright monstrous. Eventually, in the final third of the film, the voiceover places the viewer at a distance. Rodrigues’ writings stop with his capture, replaced by those of a Dutch trader, who is barely a character in the screen story, and who documents his observations of Rodrigues’ behavior. With the story no longer being told from Rodrigues’ perspective, the audience struggles to know what he’s thinking. Then again, Scorsese’s artistic gambit is that his character has been established well enough at this point, leaving the audience to make assumptions about Rodrigues’ state of mind.

From a purely aesthetic perspective, Scorsese’s treatment echoes Kurosawa and Bergman, in that the director’s longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker probably had far fewer cuts to make than any other Scorsese film in a decade. His camera work, captured by cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto in a rare rural Taiwan shoot, sprawls across the landscape in long, pensive takes. Along with the film’s scarcity of non-diegetic music, Silence contains a sobering, searching tone. It’s an elegant and relentlessly severe approach, coupled with impressive performances from Driver and Neeson, both of whom, at their worst, appear stripped-down and downright skeletal in their roles. Garfield, however, carries too modern a personality and mannerism; he’s decidedly ill-suited for a film set in the 1670s. (Example: His hair somehow remains voluminous and picture-ready, whereas Driver and Neeson seem to have the appropriate level of greasiness and filth).

With a two-hour-and-forty-minute runtime, Silence may feel like an intellectual chore, especially for those unversed in deliberately paced, faith-questioning cinema by filmmakers like Bergman, Malick, or Robert Bresson. For viewers who have faith or even question their beliefs, as Scorsese often does, the film has the potential to be a profound, deeply thoughtful, and resonating experience. Rodrigues’ desire to connect with Christ by subjecting himself to undue suffering brings about several compelling paradoxes. Why continue to force his own misery without some sort of answer to his pleas? “I pray but I’m lost. Am I just praying to silence?” he asks. For those without faith, the film may be difficult to connect with—and Ferreira’s later remarks about the earthly realm may seem appealingly logical next to Rodrigues’ often extreme, dogged faith in the first two-thirds. No matter what you believe, Scorsese’s film tests its audience with a picture that maintains an uncompromising austerity toward its purpose, yet it proves easier to appreciate than enjoy.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review