My Week With Marilyn

By Brian Eggert |

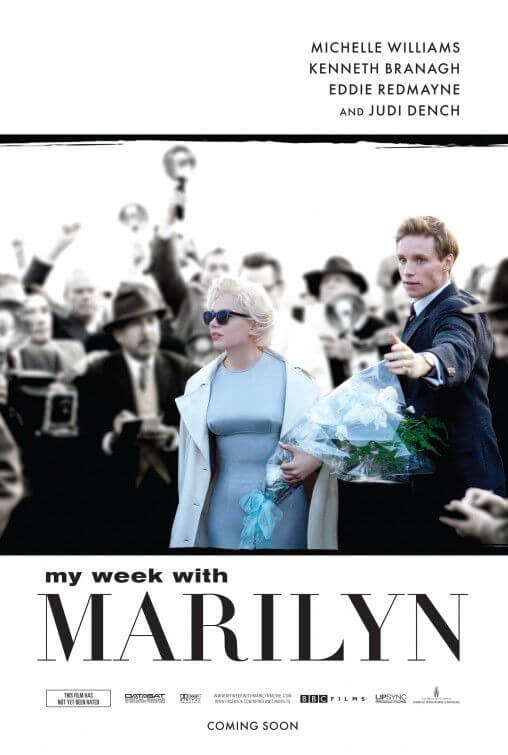

Before making her landmark turn in Billy Wilder’s Some Like it Hot, in 1956 Marilyn Monroe went to England’s Pinewood Studios to shoot The Prince and the Showgirl for director and star Laurence Olivier. She arrived with her new husband, Death of a Salesman playwright Arthur Miller, in tow, and was received by a small crowd, among them the production’s third assistant director, Colin Clark. From a prominent academic family and an Oxford graduate, the 23-year-old Clark was hired to his position, his first in show business, as a favor promised by family acquaintance Olivier. My Week with Marilyn is based on Clark’s real-life memoir of the film’s shoot, entitled The Prince, the Showgirl and Me, and details the young man’s fleeting relationship with the world’s most ogled actress.

Both opening titles and bookend narration remind us this is a coming-of-age story about Clark, here played by Eddie Redmayne (who looks like a skinless medical diagram of the human musculature, except with skin). But Clark’s inevitable growth from boy to man couldn’t be less remarkable, given his bland personality within the company of those far richer. On set, Olivier (Kenneth Branagh, wonderful), a consummate stage actor and professional, slowly loses his temper as Monroe (Michelle Williams, also wonderful) can’t seem to show up on time or remember her lines. When she does appear, Olivier’s shouting jags make her lose her focus. She’s preoccupied with working through her insecurities and building her role with “method” acting coach Paula Strasberg (Zoë Wanamaker) and “producer” Milton Greene (Dominic Cooper). At first, Clark finds himself falling for a costume girl (Emma Watson) his age, but he quickly falls for the idea of Monroe and even gathers her attention, leading to a mutual affection between the two.

TV movie veteran Simon Curtis makes his feature directorial debut and his roots are unmistakable. Curtis’ editor Adam Recht puts the film together with ungraceful cutting that can sometimes be unintentionally jarring. Though his production designer Donal Woods delivers some impressive 1950s details, Curtis does little to augment the setting cinematically. The reality of the film and that of the film-within-the-film, The Prince and the Showgirl, go undifferentiated. Another director might have used a visual style to separate the two realities, to show not only how Monroe looked offscreen, but how onscreen she became something else entirely. Beyond this, The Prince and the Showgirl is not a very good picture, or an interesting one to watch reenacted over and over. Curtis spends far too much of his 99-minute runtime laboring over Olivier’s attempts to squeeze out a stronger performance from Monroe and not enough elaborating on Clark’s story or exploring Monroe’s shattered personality.

When thinking of Marilyn Monroe, my thoughts immediately go to her appearance in Bruce Conner’s avant-garde piece, Marilyn Times Five (1973). The 14-minute experimental short features a stag video of Monroe in panties as she guides an apple over her otherwise naked body. There’s about one minute of footage in all, but Conner repeats it again and again; over the soundtrack, Conner repetitively plays Monroe’s version of “I’m Through With Love” as sung in Some Like it Hot. The consequence reminds us what a voyeuristic, reprocessed product Monroe had become by her prime—how celebrity transformed this damaged woman into a pinup, and how our culture ignored her evident problems in favor of her pretty face, peroxide-blonde hair, hour-glass figure, and large mammaries. Of course, there’s no doubt that the woman behind the Marilyn Monroe screen persona was a much more complicated and guarded figure, but so little of what makes her tick is explored within Adrian Hodges’ script.

Williams makes the most of her underwritten role by giving a performance that proves to be the film’s raison d’être. She may not be a dead ringer for Monroe, but Williams has Monroe’s mannerisms down perfectly, especially during her dance routines. There’s much Oscar talk about Williams and the film itself, thanks to The Weinstein Company’s usual end-of-year Oscar push. Harvey Weinstein will sell this thing until audiences are convinced it’s the best picture of the year, while its sloppy assembly, clumsy editing, and uninspired staging will go unnoticed because it’s almost impossible to take your eyes off Williams when she’s onscreen. The performance is rich, nuanced, and complicated in a way, even if the story itself is not. She’s helped along through the dull proceedings by her costars. Branagh creates an incredible impersonation of Olivier, while Cooper, Judi Dench, Toby Jones, and Julia Ormond keep the supporting roles interesting.

The film recognizes that Monroe has less refined skill (like Olivier’s) than instinctual presence. Whereas Olivier labored over his talents, Monroe’s ability came naturally, her command of the screen undeniable. The film calls her “the greatest actress the world has ever known,” but doesn’t question that claim by suggesting her popularity and commoditization were its origins. Her sexual objectification isn’t a problem here, and that’s a problem. Alas, the film would rather fawn over her and remember her fondly from Clark’s perspective—that of a smitten young man. Fair enough, but it doesn’t make for very compelling or challenging material. When My Week with Marilyn was over, I had no new insights or better understanding of Marilyn Monroe. What exactly was at the root of the relationship between Monroe and her acting coach? If tortured by show business, why does Monroe choose to remain in the spotlight? She loves it, of course, but why? Hints into her dual life remain mere allusions and the audience is left wanting more, no matter how good Williams may be.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review