The Definitives

Mon oncle

Essay by Brian Eggert |

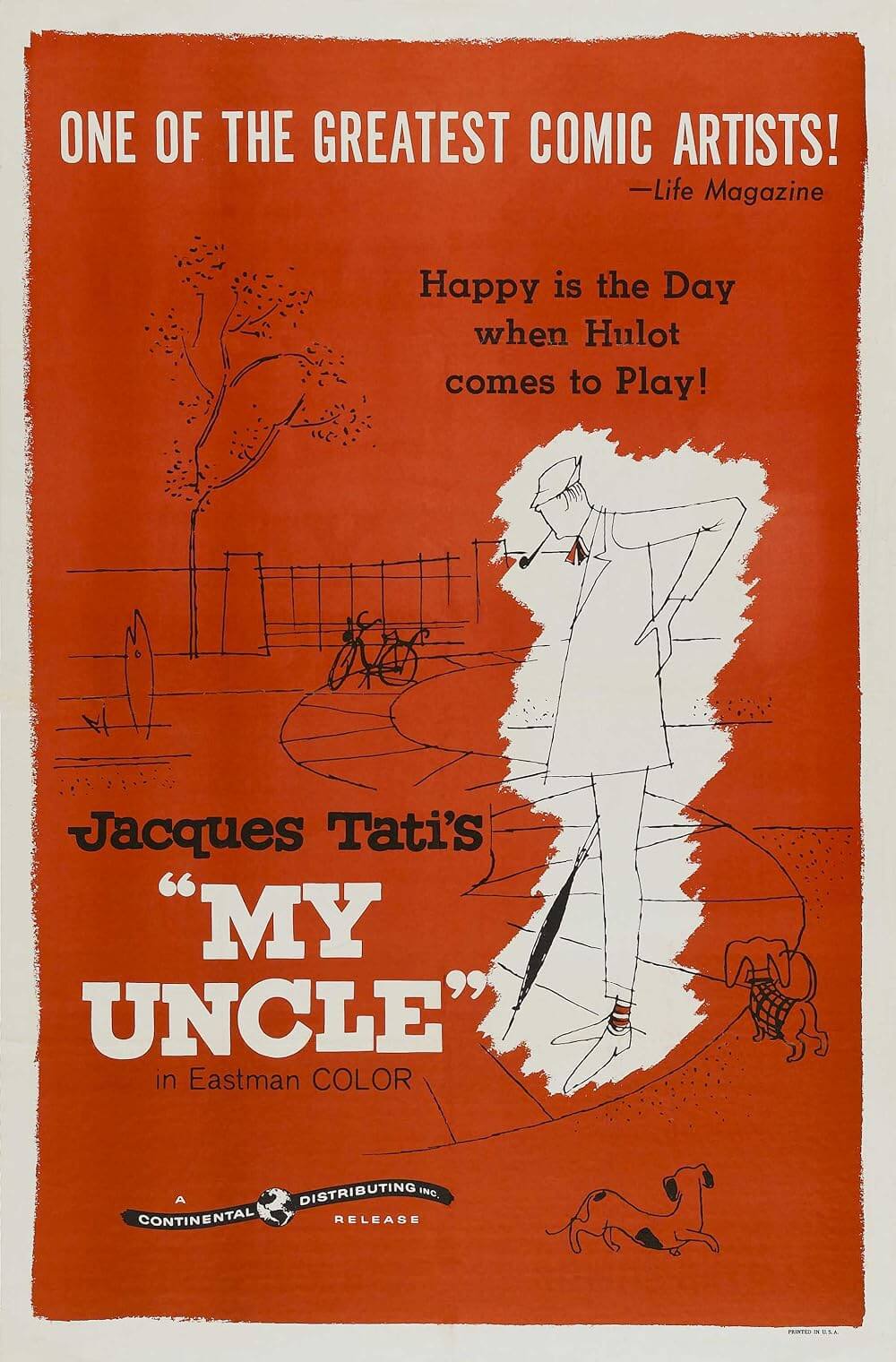

Monsieur Hulot lives in the “old quarter” of Paris. Out his top floor view from his modest flat are markets and bistros teeming with activity and fascinating characters. A band of dogs scuttles about, sniffing and scavenging and marking their territory; a chatty street-sweeper is too engrossed in his endless conversations to actually sweep; a merchant sells excessively priced produce because a flat tire on his truck causes the scale to tip. One morning, Hulot opens his window on this view and hears a bird chirping but for a brief moment. Curious, he observes the caged canary across the way and notices that his window, at just the right angle, reflects rays off a windowpane onto the bird, showering it in sunlight. Delighted, Hulot adjusts his window back and forth, and upon finding the correct angle, listens to the bird’s song, pleased by his discovery. Monsieur Hulot is always exploring how simple objects can be intriguing and beautiful, and so perhaps this is why he seems so befuddled by the unnecessary difficulty of the modern world. In Jacques Tati’s 1958 film Mon oncle, Hulot is the viewer’s entry point into two worlds that are investigated and contrasted: one world is obsessed with contemporary gadgetry and industry, the other is rooted in ways of the past.

But more than an apparent social commentary about the conflict between new and old, Mon oncle is Tati’s most touching and pleasant film, a masterpiece of physical comedy and meticulous planning, and a delicately heartrending story about family bonds. Tati’s gangly and single-minded alter-ego Monsieur Hulot appears in an ever-present fedora and tan trenchcoach; he has a long-stemmed pipe that only leaves his mouth when he taps it against the bottom of his shoe, wears pants that are too short and reveal his striped socks, and he always carries an umbrella though it never seems to rain. He walks as if bouncing on his tip-toes, his arms stretched out by his sides. His body tilts forward, since he towers over the world and must look downward to greet it. At times he looks graceful, and other times he appears composed even in his awkwardness, demonstrated through a series of precise, apologetic, curious, bewildered gestures. He tinkers with the world around him, puzzled though never disparaged by in his frequent inability to find the meaning behind objects and people; he accepts a thing or a person for what it is, and his acceptance of the world for what it is remains part of his charm.

In Mon oncle (“my uncle”), Hulot serves as the uncle of the title; his nephew, Gerard Arpel (Alain Becourt), is a young boy who prefers spending more time with his absentminded uncle than his ultra-modern parents. Gerard’s parents are both overweight and obsessed with their various doohickeys. His mother fills her days by maintaining their elaborately designed home of convenience, and his wealthy father runs an industrial factory downtown. Gerard’s école (school) looks no different from the outside than his father’s factory, but after school is reserved for uncle Hulot, who takes Gerard out on merry jaunts to the “old quarter”, where a vendor serves hotcakes in a field, and suckers distracted by the boy’s whistle walk onward into a lamppost. Bothered by Hulot and his kinship with his son, Mr. Arpel attempts to secure Hulot a job, albeit unsuccessfully, all the while regretting that his child favors his brother-in-law over him. Likewise, Mrs. Arpel attempts to play matchmaker for her hapless brother and their garish neighbor, but her efforts are also in vain. In the film’s last scene, Mr. Arpel, fed up, puts Hulot on a plane for the provinces, where he will learn how to sell cars—what Mr. Arpel has deemed a productive living. Hulot does not argue the matter, but there is some semblance of a happy ending regardless; Gerard seems to find an inkling of boyish adventure in his father, and the two form a long overdue connection.

In Mon oncle (“my uncle”), Hulot serves as the uncle of the title; his nephew, Gerard Arpel (Alain Becourt), is a young boy who prefers spending more time with his absentminded uncle than his ultra-modern parents. Gerard’s parents are both overweight and obsessed with their various doohickeys. His mother fills her days by maintaining their elaborately designed home of convenience, and his wealthy father runs an industrial factory downtown. Gerard’s école (school) looks no different from the outside than his father’s factory, but after school is reserved for uncle Hulot, who takes Gerard out on merry jaunts to the “old quarter”, where a vendor serves hotcakes in a field, and suckers distracted by the boy’s whistle walk onward into a lamppost. Bothered by Hulot and his kinship with his son, Mr. Arpel attempts to secure Hulot a job, albeit unsuccessfully, all the while regretting that his child favors his brother-in-law over him. Likewise, Mrs. Arpel attempts to play matchmaker for her hapless brother and their garish neighbor, but her efforts are also in vain. In the film’s last scene, Mr. Arpel, fed up, puts Hulot on a plane for the provinces, where he will learn how to sell cars—what Mr. Arpel has deemed a productive living. Hulot does not argue the matter, but there is some semblance of a happy ending regardless; Gerard seems to find an inkling of boyish adventure in his father, and the two form a long overdue connection.

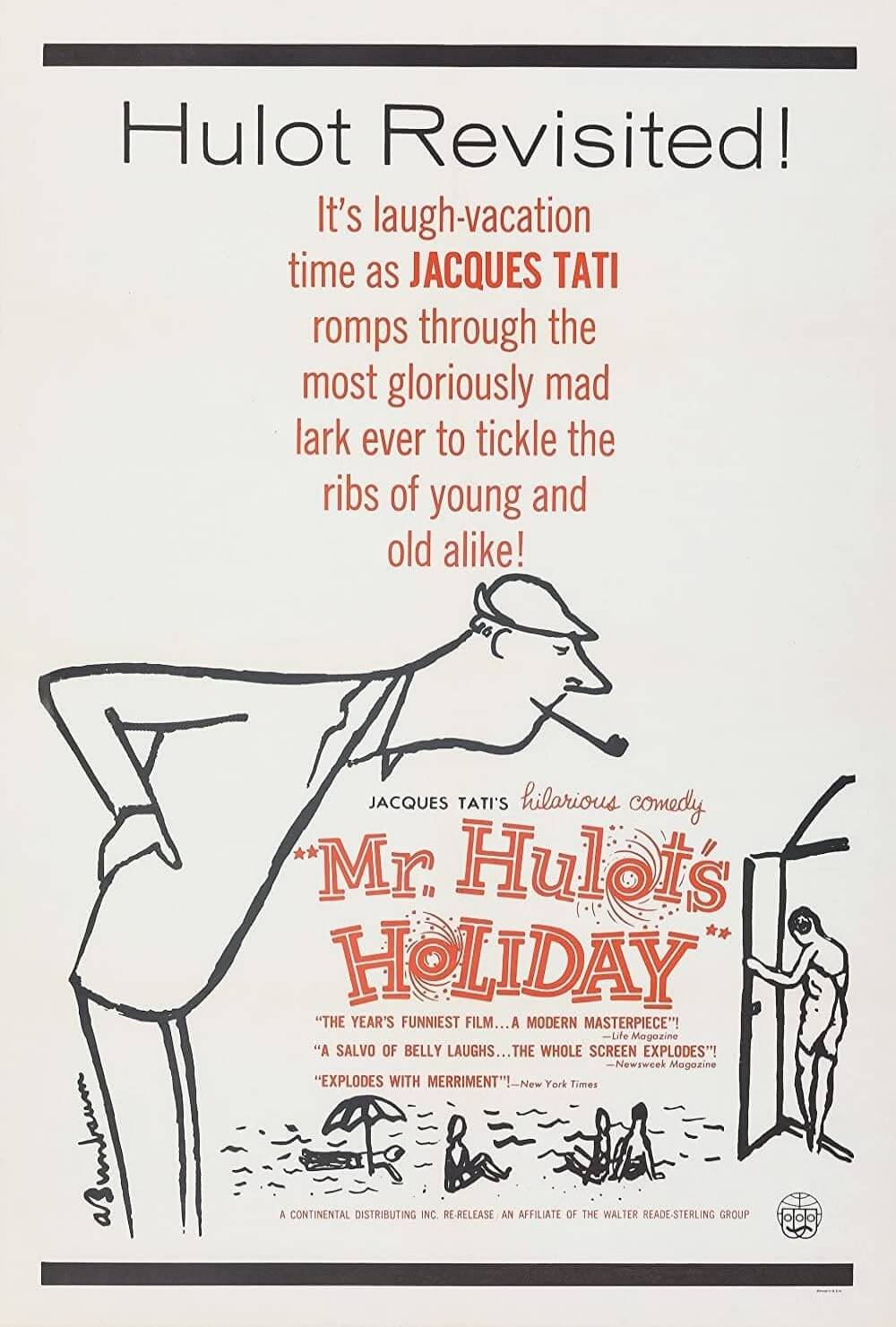

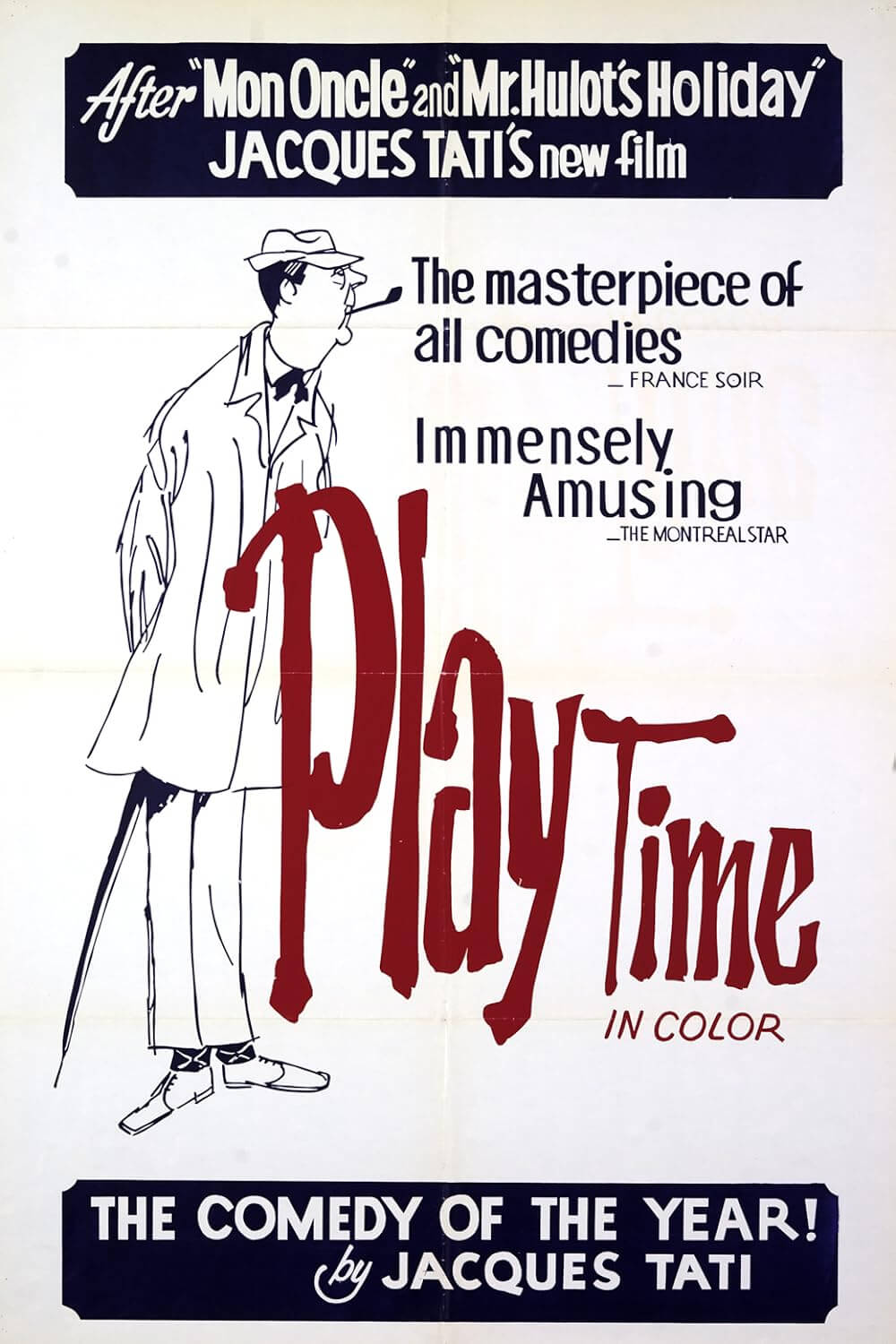

Hulot first appeared in Tati’s 1953 film M. Hulot’s Holiday, where, unintentionally, of course, Hulot enlivened a boring French resort through his bumbling; his accidental ignition of fireworks and love of jazz rumble the sleepy beachside getaway. Hulot has less direct impact in Mon oncle; he seems lost in the modern world around him, which in the last scene even absorbs and triumphs over him as he enters the airport. Although his presence has, in essence, healed the Arpel family, where does this leave Hulot? As Tati’s Hulot films evolved with PlayTime in 1967 and Trafic in 1971, the character would become progressively more eclipsed by the world of the film, while the films themselves resist narrative forms and resolve to be a series of comic observations. Gradually, Tati’s camera, already resistant to close-ups, would pull back further and further, to the extent where, at times, Hulot becomes just another detail on a screen populated by the absurdity of the modern world. Each film demonstrates how Tati is more interested in exploring broad character tropes as opposed to fleshed-out individuals and personalities, Hulot himself being the prime example.

Given his fascination with entire worlds, Tati acts as an observer and replicates what he sees through a hilarious, clever series of elaborate and yet subtle gags. In Mon oncle, consider Hulot’s first factory job, secured by Mr. Apel who pleaded with his boss for the favor. Hulot arrives at the back door of the factory and before entering unknowingly steps into some white plaster collected on the ground. With each step, he leaves a footprint behind him. He enters a secretary’s office and suddenly realizes what’s happened after trailing his own prints, so he tries to clean off his shoes before she returns, but sets them atop her desk to do so. When the secretary reenters, she sees the footprints leading from the door through her office and onto her desk, and she determines that Hulot had climbed up on her desk to look over the dividing wall to peek into the ladies’ room. She dismisses him as a Peeping Tom. Another gag is a shot from outside of Hulot’s building. We watch Rear Window-style through gaps in the façade as Hulot takes the stairs, at times disappearing and then reappearing on the opposite side of the building; at one point, a freshly showered woman wrapped in a towel heads back to her room, and we see only the good mannered Hulot’s feet as he turns to face a wall. Each gag is designed to materialize from a watching and understanding of basic actions; very often we laugh, but more often we smile at these sly morsels, so richly constructed for the patient and attentive viewer.

Given his fascination with entire worlds, Tati acts as an observer and replicates what he sees through a hilarious, clever series of elaborate and yet subtle gags. In Mon oncle, consider Hulot’s first factory job, secured by Mr. Apel who pleaded with his boss for the favor. Hulot arrives at the back door of the factory and before entering unknowingly steps into some white plaster collected on the ground. With each step, he leaves a footprint behind him. He enters a secretary’s office and suddenly realizes what’s happened after trailing his own prints, so he tries to clean off his shoes before she returns, but sets them atop her desk to do so. When the secretary reenters, she sees the footprints leading from the door through her office and onto her desk, and she determines that Hulot had climbed up on her desk to look over the dividing wall to peek into the ladies’ room. She dismisses him as a Peeping Tom. Another gag is a shot from outside of Hulot’s building. We watch Rear Window-style through gaps in the façade as Hulot takes the stairs, at times disappearing and then reappearing on the opposite side of the building; at one point, a freshly showered woman wrapped in a towel heads back to her room, and we see only the good mannered Hulot’s feet as he turns to face a wall. Each gag is designed to materialize from a watching and understanding of basic actions; very often we laugh, but more often we smile at these sly morsels, so richly constructed for the patient and attentive viewer.

Accordingly, Tati films are not what one would call chatty. Quite the opposite. By any other standards, these films would be considered borderline silent. Tati’s work has been aligned with silent masters such as Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd for a reason—because his emphasis is on physical comedy over verbalized exposition. Though all of Tati’s films contain little dialogue, Mon oncle has more than any of them. Still, his dialogue is almost superfluous within the context of the film; French audiences can ignore it, and non-French speakers can shut off their subtitles. Hulot himself almost never speaks except through his bemused expressions; other characters are so effortlessly described through their movements that we can understand each scene by body language alone. More important than dialogue are the sound effects, which, like the film’s score by Franck Barcellini and Alain Romans, rely on repetition to create a sense of ease and humor. The variance in footsteps, the squeaking of a gate, the buzz of a button, the honk of a car horn, the whistle children use to distract pedestrians—all aural cues that become more important than any single line of dialogue. Tati’s films rely on the viewer’s visual and aural observational skills. His films are demanding in that they appear to be about nothing at all, though they are complex and meticulously crafted by a perfectionist-filmmaker.

In 1955, writing for Cahiers du cinema, François Truffaut (The 400 Blows) published a long list of filmmakers whom he believed were contributing to the downturn of the French film industry; with it, he also published a much shorter list that included nine exceptions whom he believed supplied French cinemas with great artistry. Truffaut’s brief list of important French directors included Jean Renoir, Max Ophüls, Jacques Becker, Robert Bresson, Alexandre Astruc, Jean Cocteau, Abel Gance, Roger Leenhardt, and, of course, Jacques Tati. Unlike his contemporaries on Truffaut’s list, Tati was not a part of the “film community” in the active sense. He remained on the margins of this crowd, and, as offers poured in after his success with M. Hulot’s Holiday both from France’s budding television market and from Hollywood, he valued his independence even more. A famous anecdote told by Tati recounts how, after participating in interviews with the U.S. press for the release of his first Hulot picture, he was approached by a group of American film financiers. He attended a dinner at which the American businessmen each ordered obscenely large steaks. Tati watched them engorge themselves for upwards of an hour without a word until they finally wanted to talk business. “Not until you’ve finished what’s on your plate!” said Tati, effectively ending discussions—with what was perceived as degraded American money—in the name of French manners.

In 1955, writing for Cahiers du cinema, François Truffaut (The 400 Blows) published a long list of filmmakers whom he believed were contributing to the downturn of the French film industry; with it, he also published a much shorter list that included nine exceptions whom he believed supplied French cinemas with great artistry. Truffaut’s brief list of important French directors included Jean Renoir, Max Ophüls, Jacques Becker, Robert Bresson, Alexandre Astruc, Jean Cocteau, Abel Gance, Roger Leenhardt, and, of course, Jacques Tati. Unlike his contemporaries on Truffaut’s list, Tati was not a part of the “film community” in the active sense. He remained on the margins of this crowd, and, as offers poured in after his success with M. Hulot’s Holiday both from France’s budding television market and from Hollywood, he valued his independence even more. A famous anecdote told by Tati recounts how, after participating in interviews with the U.S. press for the release of his first Hulot picture, he was approached by a group of American film financiers. He attended a dinner at which the American businessmen each ordered obscenely large steaks. Tati watched them engorge themselves for upwards of an hour without a word until they finally wanted to talk business. “Not until you’ve finished what’s on your plate!” said Tati, effectively ending discussions—with what was perceived as degraded American money—in the name of French manners.

Yet, Truffaut’s validation of Tati as an artist-comedian brought about, to a degree, a self-consciousness in the actor-writer-choreographer-producer-director, in that he could not disappoint his intellectual or political audiences, while he could also not disappoint the French people. Just as Charlie Chaplin’s The Tramp was a universal figure “for the people”, Monsieur Hulot was an expressly French icon not to be sullied by Hollywood. In his rejection of Hollywood offers and resistance to television, Tati had managed to become a “pure artist” in France, both amid his fellow filmmakers and with audiences. As a result, Tati sought to infuse his future Hulot pictures with a social commentary, lending substance to the director’s arrangement of clever visual gags, elaborately conceived production design, minimalist presentation, and meticulous concentration of subtle details—all of which took precedence over the political “purpose” of the film. To be sure, Tati’s commentaries never take precedence over his stylish comedy, but they enhance the film’s sophistication simply by supplying the landscape. For Mon oncle, Tati’s social remarks are maintained in the contrast between the Arpel’s “suburban villa” and Hulot’s “old quarter” of Paris, and how ultimately modernism makes day-to-day life more complicated, despite its intentions to make life simpler.

Housing presented a major problem in postwar France; as the population increased, so did the need for living space. Most cities resolved to build upward with high-rise apartment buildings, which are seen under construction in the film’s opening title sequence. An upsurge of young architects filled needs by designing gaudy, needlessly geometric abodes similar to ones constructed a generation earlier after the First World War, with a pointed gracelessness that Mon oncle co-writer Jacques Lagrange introduced into his designs for the Arpel’s avant-garde home. Surrounded by rock gardens and twisting stone pathways, the impeccably clean and expressionless Villa Arpel is equipped with no end of electronic gizmos, buttons, and gadgets, none of which actually worked—they were operated manually offscreen by crewmembers to complete the illusion that such would-be labor-saving mechanisms actually functioned. Their garden houses an absurd fish fountain, which Mrs. Arpel is careful to turn on for her guests (all except Hulot), although visitors can see it suddenly begin to spout after they buzz at the Arpel gate, thus defeating its desired splendor with a stink of self-consciousness. Each detail was conceived to evoke a quality of needlessness and extravagance not for convenience’s sake, but for the sake of bourgeois self-satisfaction.

Housing presented a major problem in postwar France; as the population increased, so did the need for living space. Most cities resolved to build upward with high-rise apartment buildings, which are seen under construction in the film’s opening title sequence. An upsurge of young architects filled needs by designing gaudy, needlessly geometric abodes similar to ones constructed a generation earlier after the First World War, with a pointed gracelessness that Mon oncle co-writer Jacques Lagrange introduced into his designs for the Arpel’s avant-garde home. Surrounded by rock gardens and twisting stone pathways, the impeccably clean and expressionless Villa Arpel is equipped with no end of electronic gizmos, buttons, and gadgets, none of which actually worked—they were operated manually offscreen by crewmembers to complete the illusion that such would-be labor-saving mechanisms actually functioned. Their garden houses an absurd fish fountain, which Mrs. Arpel is careful to turn on for her guests (all except Hulot), although visitors can see it suddenly begin to spout after they buzz at the Arpel gate, thus defeating its desired splendor with a stink of self-consciousness. Each detail was conceived to evoke a quality of needlessness and extravagance not for convenience’s sake, but for the sake of bourgeois self-satisfaction.

The same notion applies to Tati’s representation of the modern workforce, which is defined through a series of obligatory rituals and movements. Mrs. Arpel carries out her housekeeping duties with exaggerated accents on her motions, as if acting out her role in the household though no one is there to watch her performance. Workers at Mr. Arpel’s factory, Plastac, from factory hands to the secretary pool, sit idle until Arpel himself comes around the corner to check on their progress. Even the aforementioned street sweeper cannot be bothered to sweep when a good conversation is to be had. Though Hulot does not have a job, his absence of employment is not unproductive. He provides another kind of necessity—a much more valuable commodity in Tati’s worldview. Hulot participates in the world around him, supplying a constructive form of community behavior with his polite, understanding, and very human interactions with people. Through this opposition of values, Tati argues that the most troublesome aspect about technology is how people lose touch with one another because of it. What remains ironic is how Tati toils over his production’s details, insisting on realism and painstakingly monitored consistency in a film that values cultural unity through loafing about.

Although many film historians and analyses of Mon oncle have called it a censure of modernism, Tati’s assessment seems more open-minded than some would describe it. Consider the progress of the relationship between Gerard and his father. It begins with the boy uninterested in his parents’ way of life, their fixation on conveniences making them content at home. Consequently, Gerard’s adventures with his uncle Hulot outside of the Arpel gates are instantly fascinating, but they leave his father jealous of Hulot’s rapport with the boy. Tati’s distance from his own estranged father, who died before the film was completed, inspired the story. And indeed there is a hope in the film to open a line of communication between the “old” and “new” France. As Hulot is sent away by his brother-in-law to train as a car salesman, Gerard and his father wave goodbye at the airport. To get Hulot’s attention, Mr. Arpel whistles. He fails to catch Hulot’s notice, but a man heading into the airport turns to look for the whistler and instead walks into a lamppost—an unintentional goof intentionally played by Gerard many times on his adventures with uncle Hulot. Gerard and his father duck behind their car, laughing. It is a happy ending for both, as Gerard no longer needs Hulot as a substitute father-friend, and Mr. Arpel can finally feel that his son looks up to him.

Although many film historians and analyses of Mon oncle have called it a censure of modernism, Tati’s assessment seems more open-minded than some would describe it. Consider the progress of the relationship between Gerard and his father. It begins with the boy uninterested in his parents’ way of life, their fixation on conveniences making them content at home. Consequently, Gerard’s adventures with his uncle Hulot outside of the Arpel gates are instantly fascinating, but they leave his father jealous of Hulot’s rapport with the boy. Tati’s distance from his own estranged father, who died before the film was completed, inspired the story. And indeed there is a hope in the film to open a line of communication between the “old” and “new” France. As Hulot is sent away by his brother-in-law to train as a car salesman, Gerard and his father wave goodbye at the airport. To get Hulot’s attention, Mr. Arpel whistles. He fails to catch Hulot’s notice, but a man heading into the airport turns to look for the whistler and instead walks into a lamppost—an unintentional goof intentionally played by Gerard many times on his adventures with uncle Hulot. Gerard and his father duck behind their car, laughing. It is a happy ending for both, as Gerard no longer needs Hulot as a substitute father-friend, and Mr. Arpel can finally feel that his son looks up to him.

The film illustrates a relationship between two worlds that, their differences notwithstanding, can easily coexist. This is most evident in Gerard, but more so in the gang of stray dogs who hurry about the screen, scampering between worlds in their cheerful, carefree way. We should all be so free, Tati implies. The Arpel family’s dachshund, Dacky, whose plaid sweater hilariously matches Mr. Arpel’s night jacket, sneaks out to join this band of canines on their cheerful outings. They appear in Hulot’s neighborhood scavenging through old produce, they sneak into the industrial building where Hulot applies for a job, and Dacky even joins his master at the office. Their presence may not have bearing on the plot, however they represent the film’s theme that a place is what you make of it. As for dogs, Tati often casts them in significant roles. For Mon oncle, one of the more endearing production stories details how Tati adopted the dogs from the SPA (Société Protectrice des Animaux) for the film, and after production wrapped he assured they would get a good home when he took out an ad in the paper Le Figaro announcing these “upcoming film stars” for adoption. All went to good homes.

Tati began filming in September 1956 and completed principal photography in February 1957. For a year he toiled in the editing room, mastering the dubbing process and sound effects that would become so important upon viewing the finished film. Because the dubbed English-language version of M. Hulot’s Holiday had been so successful in the U.S., Tati personally oversaw a version for his English-language audience, complete with alternate cuts, “My Uncle” written on the brick wall in the opening credits. In the English-language version, the Arpels speak in a British brogue while the peasants speak in unintelligible French jabber, suggesting English-speaking tourists could get along in France, as long as they stay out of the “old quarter” (a notion reinforced by PlayTime). Nevertheless, when Mon oncle was shown at the Cannes Film Festival in its original French, it won a Special Jury Prize (Prix Spécial du jury), having not competed for the Palme d’Or. The next year, Tati’s film took home the Academy Award for the Best Foreign Film of 1958. When he visited Hollywood for the ceremony, the Academy offered him any indulgence he could think of; Tati asked only that he be allowed to visit the nursing homes where silent film comedians Buster Keaton, Stan Laurel, and Mack Sennet then lived.

Tati began filming in September 1956 and completed principal photography in February 1957. For a year he toiled in the editing room, mastering the dubbing process and sound effects that would become so important upon viewing the finished film. Because the dubbed English-language version of M. Hulot’s Holiday had been so successful in the U.S., Tati personally oversaw a version for his English-language audience, complete with alternate cuts, “My Uncle” written on the brick wall in the opening credits. In the English-language version, the Arpels speak in a British brogue while the peasants speak in unintelligible French jabber, suggesting English-speaking tourists could get along in France, as long as they stay out of the “old quarter” (a notion reinforced by PlayTime). Nevertheless, when Mon oncle was shown at the Cannes Film Festival in its original French, it won a Special Jury Prize (Prix Spécial du jury), having not competed for the Palme d’Or. The next year, Tati’s film took home the Academy Award for the Best Foreign Film of 1958. When he visited Hollywood for the ceremony, the Academy offered him any indulgence he could think of; Tati asked only that he be allowed to visit the nursing homes where silent film comedians Buster Keaton, Stan Laurel, and Mack Sennet then lived.

What makes Mon oncle such an access point for international audiences is not only Tati’s reliance on image over sound, and on sound effects over the minimal (French) dialogue, but also the film’s subtle emotional drive which is more significant than any other in Tati’s oeuvre. M. Hulot’s Holiday presented a lovable character, but one with no backstory; Hulot was as much a mystery to the audience as he was to other vacationers in the first Hulot film—both watched his antics from afar and tried to understand this odd, yet entirely lovable character. In Mon oncle, the inclusion of Gerard and his family in relation to Hulot forms an emotional link that bonds us to him, a bond that endures through later Hulot films and even enhances them. Here we see Hulot in his natural habitat in the “old quarter”, which makes his earlier vacation and later jaunts to the city all the more distant and isolating. We see Hulot’s connection to his young nephew Gerard, how endearing that relationship is, and how strangely at peace he is with the child. Even if these scenes amount to but a few moments within the larger picture, they have a profound ability to touch our heart.

By the title, Mon oncle seems to be from the perspective of Hulot’s nephew, although the boy’s limited screentime suggests otherwise, that perhaps Hulot is a kind of universal uncle figure presented to us by Tati. If this is true, what a gift. How pleasant to think of Monsieur Hulot as Jacques Tati’s familial contribution to filmgoers—our cinematic relation who we watch in anticipation for what he will do will next, whose politeness knows no limit, and who makes us chuckle and smile endlessly. We need only to sit back and observe as he strolls about, studying little peculiarities with his inquisitive, accommodating expressions, and through his routine we feel a kinship with how interested he becomes in the commonplace, as Tati too is fascinated by everyday objects and behaviors. Tati’s film is a unique, strangely moving ramble from one amusing observation to the next; though he labors over complicated yet seemingly effortless visual gags, his final stroke of genius is how he makes it all so affecting.

Sources:

Bellos, David. Jacques Tati: His Life and Art. London: Harvill, 1999.

Chion, Michel. The Films of Jacques Tati. Toronto: Guernica, 1997.

Dondey, Marc. Jacques Tati. Paris: Ramsay, 1987.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review