Me and Orson Welles

By Brian Eggert |

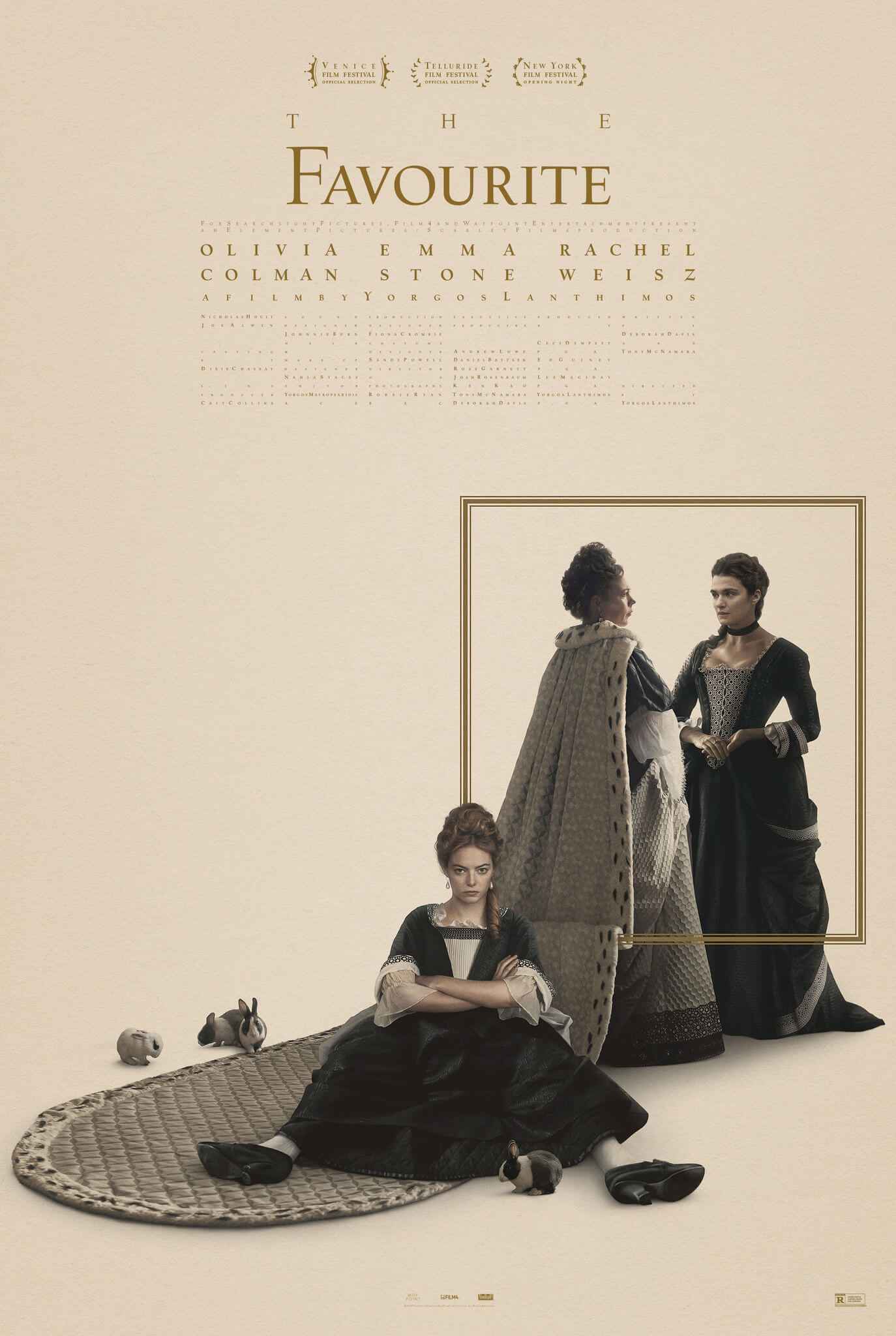

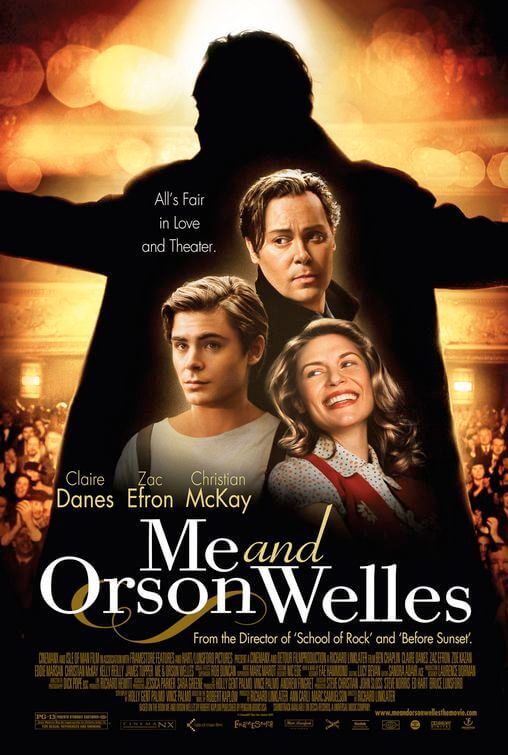

Me and Orson Welles might be about youthful bewilderment with all things art—be it great music, stirring cinema, fine paintings, or a dynamic stage production. The film seems to relish in the idea that art inspires, whereas the creation of art is toiling. For some, the appreciation of art develops into a desire to create. That desire, in rare cases, results in the discovery of exceptional and employable talent. In other, more common cases, artistic aspirations prove futile, so it becomes enough to sit back and enjoy art as a spectator. But instead of radiating such themes in the foreground, this film is content with losing its purpose behind the great performance of Christian McKay, a little-known British actor who embodies Orson Welles completely.

Director Richard Linklater’s film version of Robert Kaplow’s novel, adapted by Holly Gent Palmo and Vince Palmo, has more working against its purpose than for it. The story begins in the rich visual setting of 1937, where restless New Jersey student Richard (Zak Efron) skips school for a trip to New York City and winds up on Broadway, talking himself into a minor role in Julius Ceasar for the Mercury Theater, the troupe run by wunderkind Orson Welles. Richard is the audience’s entry point into the madness backstage, where Welles, in his brilliance, controls every detail of the famously contemporary production, wherein fascist Italy becomes a parallel to ancient Rome. Welles barks orders and directs in scenes of chaos. He insults his cast and crew, and then he whispers empty nothings into their ear to keep them from quitting. Somehow, he brings it all together just in time for opening night.

At this point in his career, Welles stood at the cusp of a breakthrough, not only by revolutionizing Broadway with his virtuoso production of Julius Ceasar but by standing before an oncoming, history-making career on stage and in motion pictures. After releasing Citizen Kane in 1941, Welles fought the moviemaking system and, in every instance, from The Magnificent Ambersons to Touch of Evil, he lost the battle. When he died, Welles’ genius was all but forgotten, waiting to be discovered again by film historians and cinephiles. Linklater’s film shows Welles before his downfall when he was still a rising star with all the potential in the world. Undoubtedly, this point in Welles’ career is meant to reflect that of the youthful Richard, a symbol of all youthful types, who has everything ahead of him. Except, Richard doesn’t have any of that necessary genius.

The star of the show is Welles, without question, though the uninteresting Richard is the film’s protagonist. Across from personalities like Welles, producer John Houseman (Eddie Marsan), and actor Joseph Cotten (James Tupper), what character wouldn’t seem bland? It’s not Efron’s fault that his role is dull in comparison to these giants, but a better actor may have been able to draw out our interest. As is, Efron feels too safe—the pretty and popular face brought in to sell Linklater’s modest drama. Efron’s Richard embarks on a sleepy journey of self-discovery, finding love in the theater secretary (Claire Danes) and friends among the Mercury’s employees, while through it all, the audience waits for McKay to reappear onscreen.

McKay goes beyond mere performance and comes close to channeling Welles’ spirit out of its slumber for one final go-round. There are moments when the lighting is angled just right and, for a brief second, McKay is the spitting image of Charles Foster Kane or Harry Lime, and the voice is the same that brought us “The War of the Worlds” radio hoax. McKay emanates Welles the actor, the director, the magician, the con man, the overconfident bastard, and, in a single important scene, the blustering front Welles erected to hide an enigmatic and sensitive persona underneath.

It’s almost painful to think about how much more fascinating Me and Orson Welles would have been had Welles himself been the focus, as opposed to just a supporting player in Richard’s story. After all, it’s a Citizen Kane-esque tale, portraying a brash mastermind who slowly reveals himself to have a soft center after all. But that’s not the film that Linklater is directing; he’s directing a much less remarkable one containing one of the great performances of 2009, and one of the great impersonations in all of cinema. It’s a small tragedy that the movie surrounding it wasn’t better, but the performance makes the film worth seeking out.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review