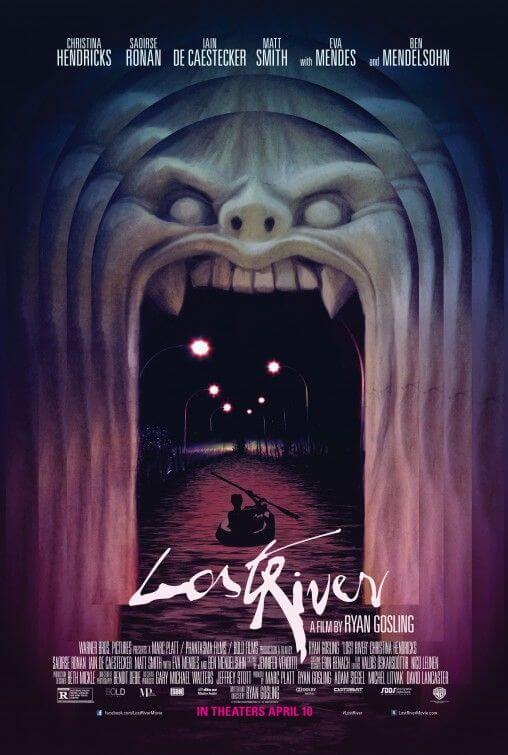

Lost River

By Brian Eggert |

In his search to represent America’s dreamy and decaying soul, writer-director Ryan Gosling fills his debut Lost River with clear evidence of his influences, from the ponderousness of Terrence Malick to David Lynch’s surrealism. Gosling’s emotionally empty but evocative picture also draws from the actor’s two-time collaborator Nicolas Winding Refn (Drive, Only God Forgives), whose own nostalgia-inflected efforts represent another evident inspiration for this gothic fairy tale set in a fictional American wasteland. Indeed, every frame of this derivative oddity piece seems to have a counterpart borrowed from another filmmaker, specifically, works like Badlands and Twin Peaks. And while Gosling cannot be faulted for using such inspired works to influence his own film, his screenplay lacks the dramatic legs to give his grandiose and often stunning imagery any significant meaning.

Stirred by miles if dilapidated Detroit neighborhoods while shooting A Place Beyond the Pines for Derek Cianfrance, Gosling decided to return there to shoot this lurid, nightmarish poem. The denizens of Lost River inhabit a few ramshackle homes leftover after their town was flooded to become host to a reservoir. Anyone who might be described as normal left long ago. Clinging to her rickety abode in a neighborhood where construction crews are tearing down the surrounding houses, jobless single-mother Billy (Christina Hendricks) lives with her two sons, teenaged son Bones (Ian De Caestrecker, from Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.) and adorable youngling Franky (Landyn Stewart). Billy talks to the bank because she’s three months behind on the mortgage, and the new seedy bank manager Dave (Ben Mendelsohn, ever typecast as slimeballs) suggests she work for his eerie underground nightclub.

The twisted sister of the Slow Club from Lynch’s Blue Velvet, Billy would be lucky if all she had to do was sing like Dorothy Vallens. Instead, she joins club regular Cat (Eva Mendes) in the hotspot’s signature acy: performances staged to look like bloody killings and other gory displays. Billy soon concocts her own performance piece: she slices her face off to reveal a crimson musculature. Meanwhile, Bones scours the city for copper to sell, avoiding the local menace Bully (Matt Smith), who rides around in a Cadillac on top of which he’s mounted a recliner, and there he sits, spouting random threats to anyone who will listen. There’s also Bones’ neighbor girl Rat (Saoirse Ronan), a would-be love interest who lives with her cracked grandma (Barbara Steele) and watches old videos for a little vintage video creepiness. Although these absurdly named characters might be interesting in other circumstances, Gosling doesn’t give them much to do, nor does he deliver a narrative that goes anywhere. The film’s original title, “How to Catch a Monster,” offers little further insight.

Instead, the director relies on hugely symbolic and overwrought visual metaphors (fire, water, destruction, creation, self-mutilation, self-recreation, and so on) to imbue the film with pseudo-significance, most of which is oversimplified and arbitrary. In the process, Gosling achieves undeniably beautiful imagery captured by Gaspar Noe’s regular cinematographer Benoit Debie: peeking out from the surface of the water over the submerged town are street lamps, which suddenly turn on one night; a house burns in the pitch of night, the structure illuminated by fire alone; the now-crumbling neighborhoods look like they were formerly those in Malick’s The Tree of Life. This is gorgeous stuff. Production designer Beth Mickle’s work deserves recognition as well for the striking club scenes, which employ neon lights and tall stages that recall similar spaces in Refn’s Only God Forgives.

And like Refn’s thin narratives, Gosling relies on powerful symbolism to carry Lost River, but he applies it too heavily, and without enough purpose to back it up. When the film debuted at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival, the characteristically impassioned audiences there reportedly booed and cheered, but mostly booed. As a result, Warner Bros. has limited the film’s theatrical release and pushed its VOD debut, knowing only a few curious cinéfiles will seek out Lost River, and fewer still will truly and unabashedly enjoy it. While trying to capture the unique styles and intentions of his betters, Gosling seems preoccupied with the look of his film more than its substance. His vague ideas about moral and existential decomposition inhabit a cumbersome viewing experience that remains admirable at times, but never engaging.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review