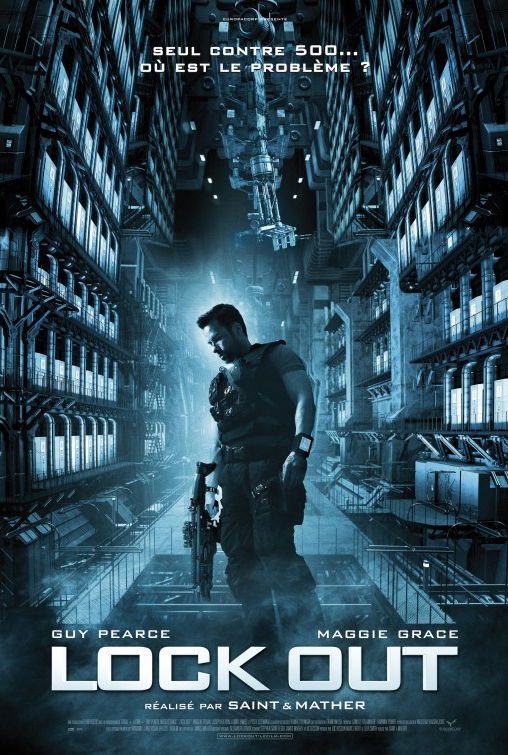

Lockout

By Brian Eggert |

Producer and co-writer Luc Besson describes Lockout as “Taken in space.” It’s the kind of movie that’s best described by comparing it to other movies. Responsible for everything from The Transporter to From Paris with Love to Liam Neeson’s recent status as an action hero, Besson’s action movie factory delivers very often dumb but occasionally entertaining action movies, none of which are as effective as Besson’s own projects as writer-director (see The Professional or The Fifth Element). Instead, this French producer hires young and very often incompetent directors to compose his cookie-cutter movies. Filmmakers like Olivier Megaton (Colombiana) and Louis Leterrier (Transporter 2) have no particular style beyond loud and impenetrable; they make Michael Bay seem watchable by comparison. The same can be said for Lockout’s directors and co-writers, first-timers James Mather and Stephen St. Leger.

Working from what’s credited as Besson’s “original idea,” the filmmaking duo borrows heavily from too many sources to ignore. Here you’ll find evidence of Die Hard, Escape from New York, and even Star Wars. Almost every scene or story element feels familiar in one way or another, so much so that enjoying the movie on its own terms becomes impossible. Besson’s idea follows a roguish hero tasked with breaking the U.S. President’s daughter, Emilie (Maggie Grace, hence the Taken similarity), out of MS-1, a maximum-security prison orbiting Earth that houses its prisoners in deep-freeze stasis. Guy Pearce plays the central badass named Snow, a character spliced together from bits of John McClane and Snake Plissken. Snow must fly by space shuttle and be covertly delivered to the prison, where he must get by 500-plus escaped prisoners, rescue the President’s daughter, and return her safely to Earth. All of this must happen in a very short span of time. Since modern shuttle launches take endless months of planning and space flights are staggeringly slow, we can assume there will be many advances in space technology between now and 2079, when the movie takes place.

Filled with snappy comebacks and annoying one-liners, the wrongly accused Snow, an ex-CIA operative, must clear his tarnished name by taking on this impossible task, which, of course, can only be accomplished by one man. Convenient he was around. And isn’t it convenient that the sole witness who can prove Snow’s innocence, Mace (Tim Plester), is also aboard MS-1? Do you think Snow might swing by and help Mace escape after he rescues Emilie? Probably. Trouble is, Emilie originally visited the station on a humanitarian mission to investigate reports of prisoners with neurological side effects to their stasis. And wouldn’tcha knowit, Mace just-so-happens to be one of them; his sudden dementia and stuttering, half-finished sentences don’t help Snow get that crucial piece of information he needs to clear his name. An unfortunate coincidence, to be sure. This is a movie filled with unfortunate coincidences and conveniences. For example, when the sole means of escape is launched into space with no one aboard, all hope seems lost. Except, everyone forgot to mention that there’s a second way to escape MS-1. Convenient, no?

Each scene looks abridged and hastily assembled, and it feels like we’re missing crucial information thanks to the sloppy cutting. Editors Eamonn Power and Camille Delamarre may have been frozen and then thawed from stasis themselves, as their efforts are just as jumbled and incoherent as Mace’s Rain Man routine. Mather and St. Leger spend no time dwelling on their own production’s sometimes neat special FX. Expensive CGI was no doubt used to render MS-1, but I couldn’t tell you what the space station looks like. There isn’t a steady master shot in this whole movie. The cuts are so frantic, the shots so limiting that the audience has no hope of understanding the movie’s sense of time and space or how characters get from Point A to Point B. In the opening, there’s a motorcycle chase sequence in a futuristic city, but the scene looks like it was shot through a Vaseline filter—but it might’ve just been a trailer for a videogame. The filmmakers are rushing to cram in as much plot as they can within a typical Besson runtime of 95 minutes while also cutting away during potentially bloody scenes to assure the ideal PG-13 rating, that the result feels like an edited-for-television version of itself.

Lockout doesn’t take itself seriously, and it doesn’t have to, but it’s not a parody either. With this level of B-movie generics, no one expects high art. What audiences should be able to expect is some degree of visual or story cohesiveness, which this movie completely lacks. The directors take a promising idea and mishandle every element, delivering a disorganized mess and, ultimately, a missed opportunity. However appealing a Guy Pearce anti-hero may be, his onscreen presence isn’t enough to make his hammy dialogue or the movie’s silly plot worth enduring. By the end, after our protagonists fall to Earth from space in a safe parachute landing, the movie wraps up its random conspiracy threads in an inelegant sequence bound by more of those conveniences I mentioned earlier, and the audience has long since given up on the nonsensicality of it all. After the first few scenes, the whole thing proves too stupid to tolerate, even during the laziest of moviegoing moods.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review