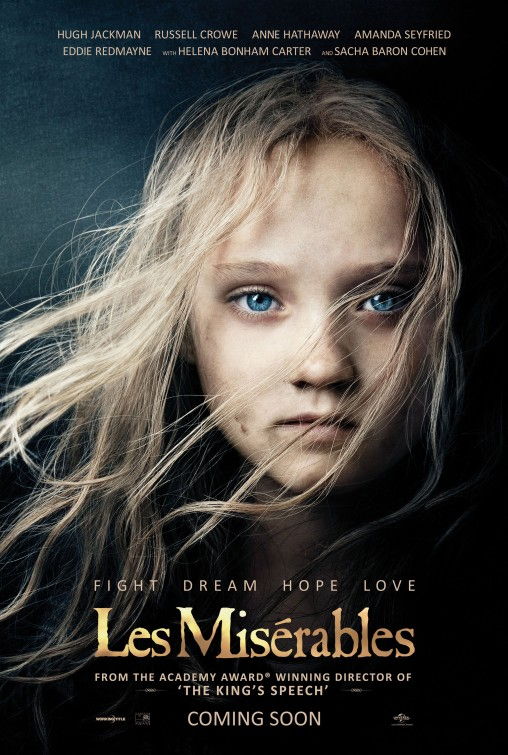

Les Misérables

By Brian Eggert |

Victor Hugo’s colossal, 1,200-page novel Les Misérables has been adapted to film dozens of times since its publication in 1862. Cinematograph pioneers the Lumière brothers made the first version in 1897 and other notable translations followed, including a Jean Gabin-starrer in 1958 and a 1998 version featuring Liam Neeson and Geoffrey Rush. The greatest adaptation remains Raymond Bernard’s more than 4-hour epic from 1934, a sweeping production that has yet to be matched in depth or breadth. Director Tom Hooper’s new film of Les Misérables is less a product of Victor Hugo and based more on Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg’s musical adaptation that debuted in 1980 and has been followed with renowned popularity ever since. Hooper brings an appropriate sense of grandness to the musical, using modern technologies to enhance the visual scope and a touch of authenticity behind his actors’ vocals, but overall, the creative choices call more attention to how it was made and distract from the powerful story.

Those unfamiliar with Hugo’s sprawling tale should become initiated elsewhere. Center is Jean Valjean (Hugh Jackman), a criminal imprisoned for 19 years for stealing a loaf of bread. Once paroled, he runs and eventually vows to make a better man of himself as a wealthy mayor and businessman, while a former prison guard turned police inspector named Javert (Russell Crowe) trails Valjean like a hound. When Valjean takes pity on a dying ex-employee, Fantine (Anne Hathaway), who, out of desperation, has become a prostitute, he declares that he will raise her daughter, Cosette (Isabelle Allen as a child; Amanda Seyfried as a young woman), as his own. When she grows older, Cosette falls for young revolutionary Marius (Eddie Redmayne), but her father Valjean wants only to keep her safe. Balancing his devotion to Cosette and his constant running from Javert, Valjean must prove to himself and Javert that a former criminal can change and redeem himself. Such themes are basic and universal, but they’re hardly resonant in Hooper’s hands.

For the film’s nearly fifty musical numbers, Hooper, an Oscar-winner for his freshman directorial effort on The King’s Speech, made the choice to record his actors singing live during filming, as opposed to being prerecorded—the standard for musicals. This method, last used to ill effect on Peter Bogdanovich’s At Long Last Love (1975), brings an immediacy to the vocals that a prerecording might not. However, viewers will find themselves drawn into the singing itself more perhaps than they normally would, more so even than what the characters are singing about. Hooper obviously found himself drawn in as well, since he frames every musical number in almost the exact same manner as the last, one after another to annoyingly repetitious consequence. After an early, beautifully sung and acted aria by Hathaway where her Fantine pours out her woes in an extended close-up, Hooper repeats this tight framing in nearly every subsequent sequence. Never has there been an adaptation of Les Misérables so devoted to its performers’ faces over the expansive setting of nineteenth-century Paris.

Granted, out of necessity, given his choice to record the actors “live,” close-ups allow Hooper to concentrate on one actor at a time, instead of having to orchestrate an entire ensemble of singers within a single composition. From a production standpoint, this is ideal, and no doubt made for a faster shoot; from a viewership perspective, the limited variation of shot types becomes redundant within the first half, and downright frustrating by the conclusion. What’s most criminal about Hooper’s choice is that he squandered the gorgeous interior and impressive exterior sets constructed under production designer Eve Stewart, in most cases augmented by believable CGI. The possibility for immense scope is further curtailed by cinematographer Danny Cohen’s inelegant handheld camera and prevalent wide-angle lenses (no one but Terry Gilliam should be using this many wide angles), while Melanie Ann Oliver and Chris Dickens edit the picture together and create the occasional confusion of time and space within a given scene.

The film’s saving grace, if one exists, resides in a handful of excellent performances, a number impressive more for their vocal talents than the character portrayed. Jackman, with his musical background, and Crowe, with his rocker history, both lend their considerable talents. Hathaway’s presence in the first act steals the show in terms of dramatic thrust; her performance of “I Dreamed a Dream” is something special, whereas Helena Bonham Carter and Sacha Baron Cohen provide some much-needed comic relief as two small-time crooks. Jackman and Hathaway lost upwards of thirty pounds each to look their most emaciated for their roles; they seem to be putting the most emotion into their performances as well. Just as in Mamma Mia!, Seyfried’s chirpy, high-pitched vibrato is grating on the ears, and Redmayne’s faux-operatic tenor is unexpected if unexciting.

With a few catchy tunes (“Lovely Ladies” and “Master of the House” come to mind) standing out among a seemingly endless slur of flattened notes in drearily sung conversations, one begins to ache for some straight dialogue between these fine actors. There’s a lot of emotion up there on the screen, and plenty of melodrama to go around, but the methods employed by Hooper to present such drama put us at a distance. An over-reliance on close-ups makes watching, as the film cuts from one giant face on the screen to the next, an uninvolving experience when the grand emotions of Hugo’s narrative should be anything but. Les Misérables is an ambitious production whose main roles were ideally cast, but Hooper’s creative risks failed to pay off in the ways he’d hoped, and instead, he took soaring material to surprising lows. Then again, devoted fans of the musical will probably enjoy and make apologies for the film. But rather than jumping on the critical and commercial bandwagon that surrounds this film and musical, you might try seeking out Bernard’s version and prepare yourself for something truly awe-inspiring.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review