Reader's Choice

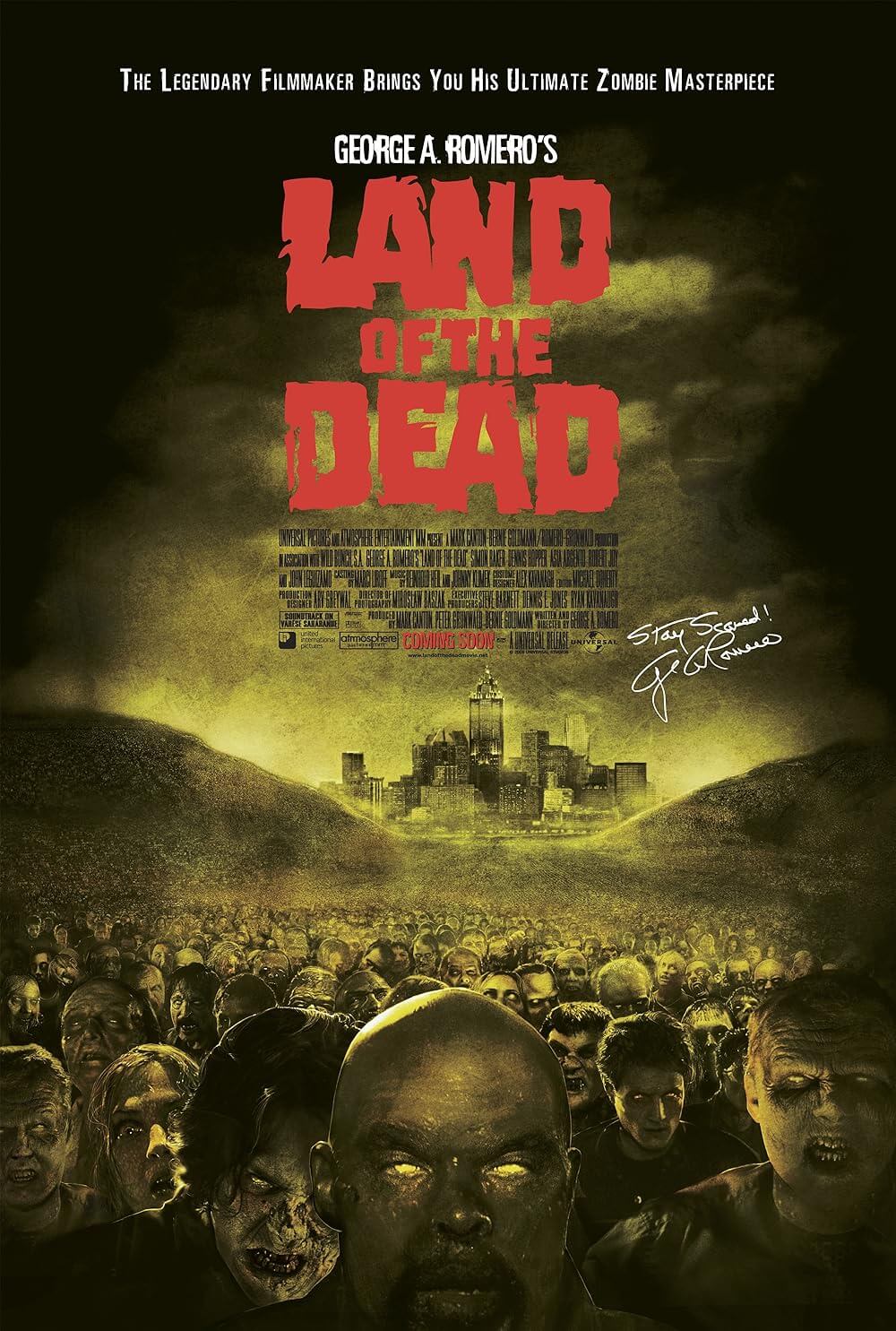

Land of the Dead

By Brian Eggert |

“When the people shall have nothing more to eat, they will eat the rich.”

– Jean Jacques Rousseau

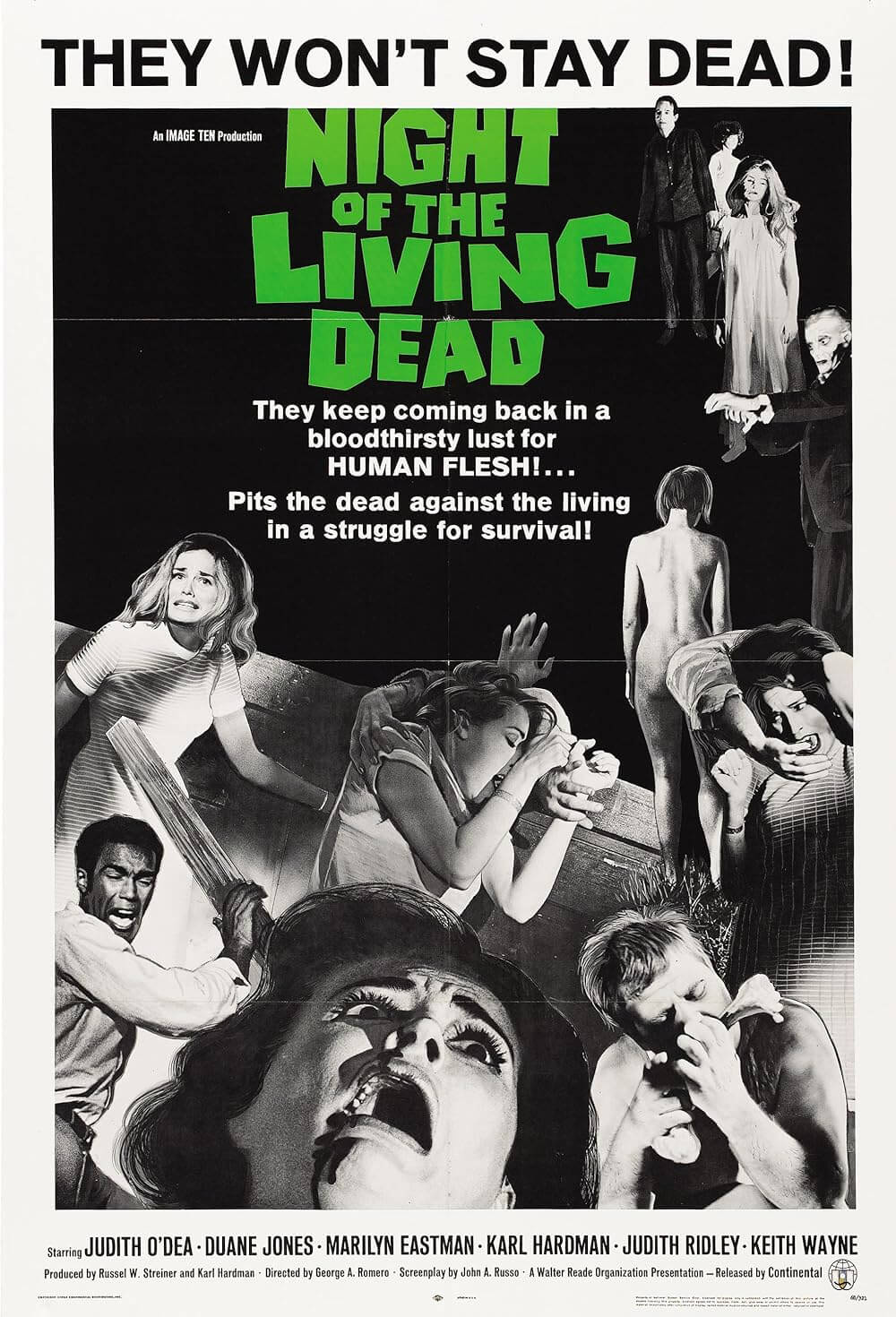

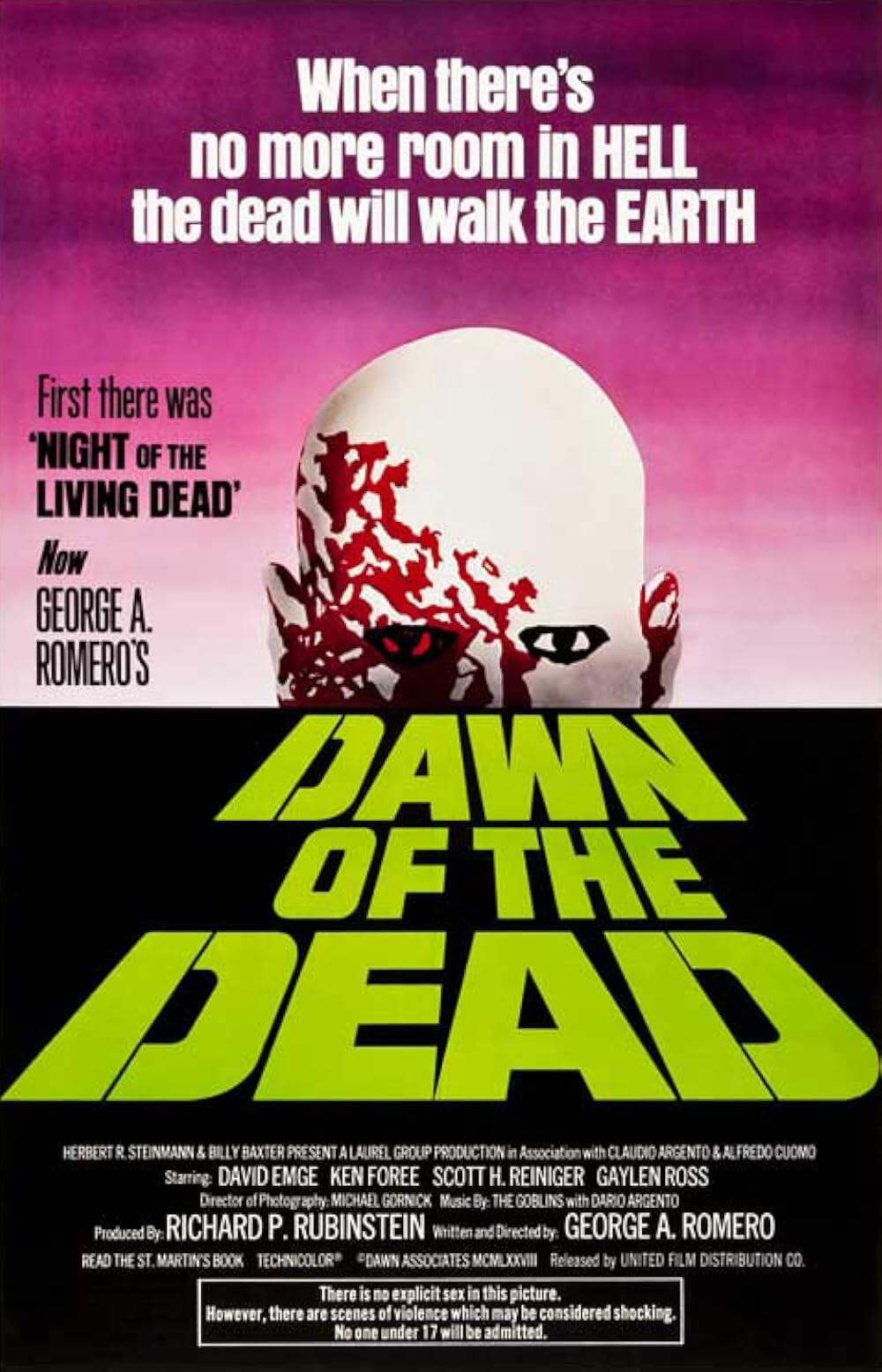

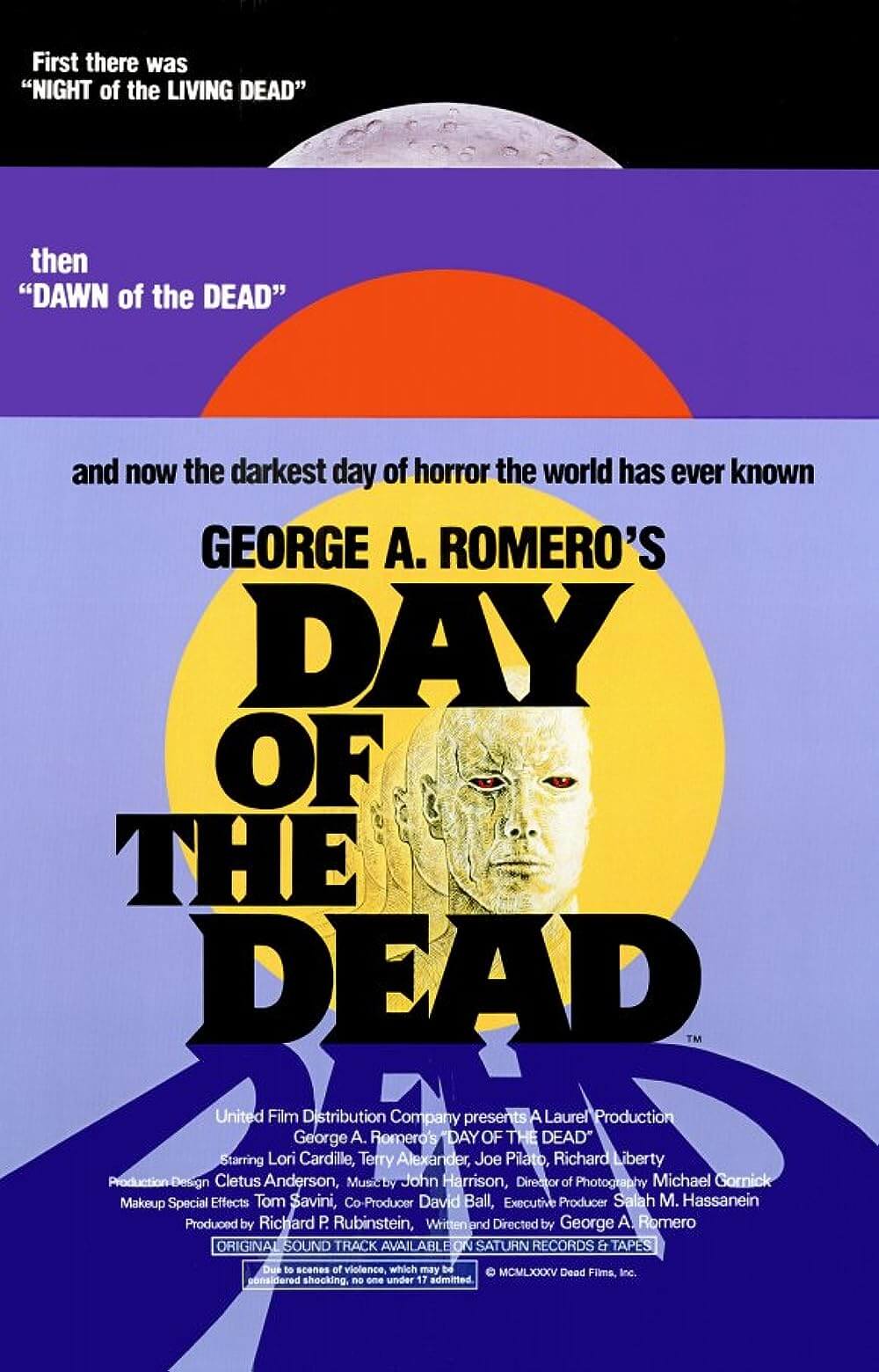

In the opening shots of George A. Romero’s Land of the Dead, we see three former members of a brass band, now zombified. They stand in a gazebo, clinging to their trombone, tuba, and tambourine, pathetically trying to make music. Doubtlessly, these three flesh-eaters didn’t meet their demise in this exact spot. We can presume that, at some point early in the apocalypse, they died and became zombies. Eventually, they collected their instruments and returned here, clinging to some vague memory of what and who they used to be. The motif of zombie consciousness permeates Romero’s zombie films; however, when Land of the Dead was released in 2005, the world hadn’t seen a new entry in his of the Dead series for twenty years. Of course, Romero originated zombie horror and mastered its socio-allegorical potential back in 1968 with Night of the Living Dead; he furthered its potential in 1978 with the consumer satire Dawn of the Dead; and again in 1985 with Day of the Dead, his takedown of governmental institutions. Land of the Dead takes a bite out of class disparity, capitalism, and George W. Bush’s presidential administration, framing the zombie as an underclass that finally snaps out of its complacency and forms a rebellious collective power.

Romero’s return followed the re-popularization of zombies after Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002) from Fox, the Resident Evil series from Sony, but most of all Zack Snyder’s remake of Dawn of the Dead and Edgar Wright’s zom-rom-com Shaun of the Dead—both distributed by Universal within a month of each other in 2004. Universal quickly turned to the auteur behind zombie cinema to re-establish himself as the Master of the Living Dead, giving him his largest budget to date, around $18 million, about $15 million more than Day, his last of the Dead film at that point. Romero’s new film became the equivalent of James Cameron’s Aliens (1985) to that franchise: a bigger, more expensive, more lavish production filled with machine guns, impressive effects, and sweeping ideas. Whereas Romero’s previous zombie films contained confining settings (a farmhouse, a mall, an underground bunker), Land of the Dead too limits space, but on a grander scope—within an entire sectioned-off city, albeit a microcosm of American class hierarchies, veiled under seemingly perpetual night.

The story begins well after Romero’s previous zombie films, when the apocalypse has long since dominated the planet. Hundreds of survivors pack into a few square city blocks, a spot at the center of Romero’s own Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where high-rise buildings look down at the surrounding squalor. Fenced-off or protected by water on all sides, the survivors endure by clinging to their former lives. The underprivileged survive on the street, distracted by vices ranging from gambling to prostitution. A fortunate few live in Fiddler’s Green, the Trump-like tower at the hub of their new civilization, where leaders still hold board meetings and bank vaults still serve their intended purpose. All behave as if society will someday return to normal, as if the world hasn’t already ended. As a result, the zombies almost feel like an afterthought until they’re smashing down walls and eating the living. “The story is happening around [the zombies] and nobody is paying attention,” Romero told interviewer Giulia D’Agnolo-Vallan. “The way nobody today is paying attention to global warming, or the reason why we Americans are so disliked everywhere else. In my mind, this film was always about ignoring the problem.” Jim Jarmusch would echo Romero’s sentiments and themes with his own zombie film in 2019, The Dead Don’t Die.

The story begins well after Romero’s previous zombie films, when the apocalypse has long since dominated the planet. Hundreds of survivors pack into a few square city blocks, a spot at the center of Romero’s own Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where high-rise buildings look down at the surrounding squalor. Fenced-off or protected by water on all sides, the survivors endure by clinging to their former lives. The underprivileged survive on the street, distracted by vices ranging from gambling to prostitution. A fortunate few live in Fiddler’s Green, the Trump-like tower at the hub of their new civilization, where leaders still hold board meetings and bank vaults still serve their intended purpose. All behave as if society will someday return to normal, as if the world hasn’t already ended. As a result, the zombies almost feel like an afterthought until they’re smashing down walls and eating the living. “The story is happening around [the zombies] and nobody is paying attention,” Romero told interviewer Giulia D’Agnolo-Vallan. “The way nobody today is paying attention to global warming, or the reason why we Americans are so disliked everywhere else. In my mind, this film was always about ignoring the problem.” Jim Jarmusch would echo Romero’s sentiments and themes with his own zombie film in 2019, The Dead Don’t Die.

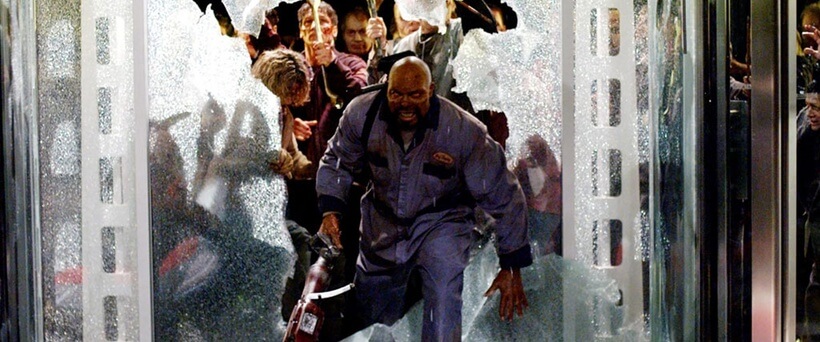

In Land of the Dead, only our resourceful hero Riley (Simon Baker) and his facially scarred sharpshooter friend Charlie (Robert Joy) know better than to ignore zombies. They see the worst of their situation on scavenging missions for their city’s leader, Kaufman (Dennis Hopper), the one-percenter who runs everything. During their latest supply run in a nearby town crawling with what are usually mindless living dead, Riley observes one of the “stenches” demonstrate problem-solving skills. He’s frightened and worries about the zombies getting more intelligent, so he plans to leave. But Kaufman arranges an arrest to keep Riley around. Elsewhere, Kaufman’s top dog, Cholo (John Leguizamo), dreams of a place in Fiddler’s Green but has no real chance at upward mobility because he’s “the wrong kind,” as Riley observes. When Kaufman confirms as much, Cholo retaliates, stealing Dead Reckoning—an elaborate, well-armed war machine that can withstand any zombie threat—and holds the city for ransom. Kaufman offers Riley, Charlie, and their new compatriot Slack (Asia Argento) freedom if they recover his vehicle.

But then Romero plays a devilish trick on the viewer with Land of the Dead. He invests us in the class conflict between Kaufman, Cholo, and Riley’s crew to emphasize the meaninglessness of their squabbling over money and property. Kaufman presides over a society dependent on collecting old supplies and canned food—there’s no attempt at agriculture or sustainability. Kaufman has recreated a short-sighted and decidedly American capitalist system that cannot last on its existing resources. And while they’re fighting amongst themselves for a scrap of power or taste of the good life, the zombies enter the picture and reveal the illusory nature of their world—the self-deception that will mean their demise. When Riley spies a problem-solving zombie, he sees Big Daddy (Eugene Clark), a thinking flesh-eater who teaches others to ignore the “sky flowers,” the name for the fireworks Riley’s team shoots into the sky to distract the undead. Big Daddy snaps zombies out of their daze and becomes their leader. Suddenly, zombies no longer saunter about without purpose; rather, though still hobbling, they trail behind Big Daddy toward a light in the distance, toward Fiddler’s Green.

Romero’s zombies evolve with each new film, proving there’s more going on in their rotting skulls than the mindless hunger to consume human flesh demonstrated in Night. In Dawn, the undead have latent memories, an attraction toward the shopping mall where survivors hole-up—as one of them says, “They’re after the place. They don’t know why. They just remember. Remember that they want to be in here.” The mad doctor Logan in Day hypothesizes that the undead could be taught manners and thus civilized; his living example was “Bub,” a zombie that salutes soldiers and would prefer to shoot someone than turn them into lunch. In Land, Big Daddy incites a revolution. He grunts orders, shows his fellow zombies how to use tools, and dispels Day’s island-getaway fantasy when he leads the throng into the water and emerges on the haven side. Big Daddy even shows pangs of emotion when the living shoot down his kind, leading to a mercy killing that puts one disembodied zombie head out of its misery. Our zombie leader’s pain is visible, and his eventual taking of Fiddler’s Green and killing of Kaufman are victories. Romero never plays Big Daddy as a villain, either. Instead, he’s every bit an underdog as Riley or Cholo—just trying to usurp The Man.

Romero’s zombies evolve with each new film, proving there’s more going on in their rotting skulls than the mindless hunger to consume human flesh demonstrated in Night. In Dawn, the undead have latent memories, an attraction toward the shopping mall where survivors hole-up—as one of them says, “They’re after the place. They don’t know why. They just remember. Remember that they want to be in here.” The mad doctor Logan in Day hypothesizes that the undead could be taught manners and thus civilized; his living example was “Bub,” a zombie that salutes soldiers and would prefer to shoot someone than turn them into lunch. In Land, Big Daddy incites a revolution. He grunts orders, shows his fellow zombies how to use tools, and dispels Day’s island-getaway fantasy when he leads the throng into the water and emerges on the haven side. Big Daddy even shows pangs of emotion when the living shoot down his kind, leading to a mercy killing that puts one disembodied zombie head out of its misery. Our zombie leader’s pain is visible, and his eventual taking of Fiddler’s Green and killing of Kaufman are victories. Romero never plays Big Daddy as a villain, either. Instead, he’s every bit an underdog as Riley or Cholo—just trying to usurp The Man.

How ironic, then, that Romero cast Hopper, the counterculture icon of the sixties, as Kaufman. Hopper plays him coolly methodical like Donald Rumsfeld, with a touch of absurdity worthy of Dub-Yah (Kaufman picks his nose at one point and reflects, “Zombies, man. They creep me out.”). It’s fitting that Land of the Dead portrays zombies as the disenfranchised and marginalized, led by a powerful Black man in Big Daddy. Eventually, and all-too-appropriately, Cholo, the Latin-American killer who dreamed of living in Kaufman’s ivory tower, joins the ranks of the dead. Romero’s casting calls out American sociopolitical hierarchies for their racist and classist roots, creating an allegory for the growing divide between the ultra-rich and the people, vastly people of color, working to support them. With this in mind, zombies become a strangely liberated entity, rising out of their complacency against The Powers That Be to strike them down from their tower and, well, eat the rich. The film might conversely, and ironically, be called Land of the Free, as the undead consciously reclaim their city. Riley and his company arrive in the aftermath with nothing to do except escape the city onto the open road. As a horror movie, this ending proves somewhat anticlimactic; but it’s a bold statement.

However, not every aspect of Land of the Dead is so carefully considered as its allegory. Along with the bigger budget come the unfortunate trappings of a major studio release, including a generic score credited to Reinhold Heil and Johnny Klimek. The few random topless women and a scene of two lesbians making out feel like cheap bits of exploitation for a director who rarely uses sex appeal for thrills. Worse, his screenplay’s treatment of Charlie leads to a few cringe-worthy scenes of corny dialogue. Early on, the dim-witted sharpshooter looks at the “sky flowers” for what must be the hundredth time and yet observes, “These here ain’t the kind of flowers you lay on the ground, these here are sky flowers, way up in heaven.” Helpful though he may be when it comes to saving lives with precise shooting, he’s the kind of clichéd magical idiot that plays insultingly, if not for his occasional amusing quip. “Just look at me,” he says, referring to his half-burned face, “you can tell I have terrible dreams.” The Lennie and George dynamic aside, Land of the Dead doesn’t feel like Romero’s other films. It’s not something he scraped together with a shoestring budget, calling in favors among friends to fill out his cast. Romero has studio money and resources behind him, and that seems to limit his necessity for formal experimentation—which is to say, the film looks a bit too much like other studio films.

The studio not only tamed Romero’s edgy aesthetic but softened his depiction of blood and guts. The theatrical version, annoyingly wrought with zombies passing over the frame during particularly nasty scenes—like the digitally inserted orgy spectators in Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999)—reflects a time before AMC’s The Walking Dead. Now, basic cable viewers can see Land of the Dead’s same special make-up effects company KNB EFX Group out-gross the previous week’s episode with monumentally grotesque sights. In the past, Romero’s low-budget work has been deemed too graphic and released Unrated, which meant his films appeared on fewer screens but had Romero’s complete vision. Universal required Romero to deliver an R-rated product to ensure wide distribution, leaving his “Unrated Director’s Cut” to live on home video platforms—complete with the conveniently placed gore-blockers removed. But even in its censored form, Land of the Dead managed to spark controversy, as Romero’s films have always been the subject of debates, protests, and bans. Ukrainian representatives, for example, banned the film on these grounds: “The memory of the Holodomor [a famine in the country that killed millions and induced cannibalism in some areas] of 1933 is still fresh in our society. A movie with scenes of people being eaten alive should not be given the go-ahead.” Indeed, Romero’s film contains those horrible scenes of bloody cannibalism we’ve come to expect from his work, rendered even more potent by the film’s impressive effects. However, after umpteen seasons of The Walking Dead and its spinoffs, the violence might seem like white noise.

The studio not only tamed Romero’s edgy aesthetic but softened his depiction of blood and guts. The theatrical version, annoyingly wrought with zombies passing over the frame during particularly nasty scenes—like the digitally inserted orgy spectators in Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999)—reflects a time before AMC’s The Walking Dead. Now, basic cable viewers can see Land of the Dead’s same special make-up effects company KNB EFX Group out-gross the previous week’s episode with monumentally grotesque sights. In the past, Romero’s low-budget work has been deemed too graphic and released Unrated, which meant his films appeared on fewer screens but had Romero’s complete vision. Universal required Romero to deliver an R-rated product to ensure wide distribution, leaving his “Unrated Director’s Cut” to live on home video platforms—complete with the conveniently placed gore-blockers removed. But even in its censored form, Land of the Dead managed to spark controversy, as Romero’s films have always been the subject of debates, protests, and bans. Ukrainian representatives, for example, banned the film on these grounds: “The memory of the Holodomor [a famine in the country that killed millions and induced cannibalism in some areas] of 1933 is still fresh in our society. A movie with scenes of people being eaten alive should not be given the go-ahead.” Indeed, Romero’s film contains those horrible scenes of bloody cannibalism we’ve come to expect from his work, rendered even more potent by the film’s impressive effects. However, after umpteen seasons of The Walking Dead and its spinoffs, the violence might seem like white noise.

Neither Romero’s gory spectacle nor his larger-than-average budget distracts too much from Land of the Dead’s thematic power, which still feels relevant in the wake of Trumpism and the continued hardening of cultural dividing lines. Following his minor but profitable box-office achievement with Land of the Dead, Romero’s career should have been revived; instead, it petered out with his last two features, Diary of the Dead (2007) and Survival of the Dead (2009), before his death in 2017. So many disposable zombie movies have attempted little more than cheap thrills in his shadow, but Romero outclasses them with his last great social commentary. And while the twenty-first century’s fast-moving zombies may have revised Romero’s original vision into occasionally fun, commercially successful products like Zombieland (2009) and World War Z (2013), they feel empty by comparison. Nothing quite punctuates his themes or suggests complacency and disenfranchisement than the deliberate lurch of Romero’s living dead. If Land of the Dead doesn’t have Romero’s usual edge, as its critics often note, then it’s at least a damn good zombie film that surpasses his imitators.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted on Patreon.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review