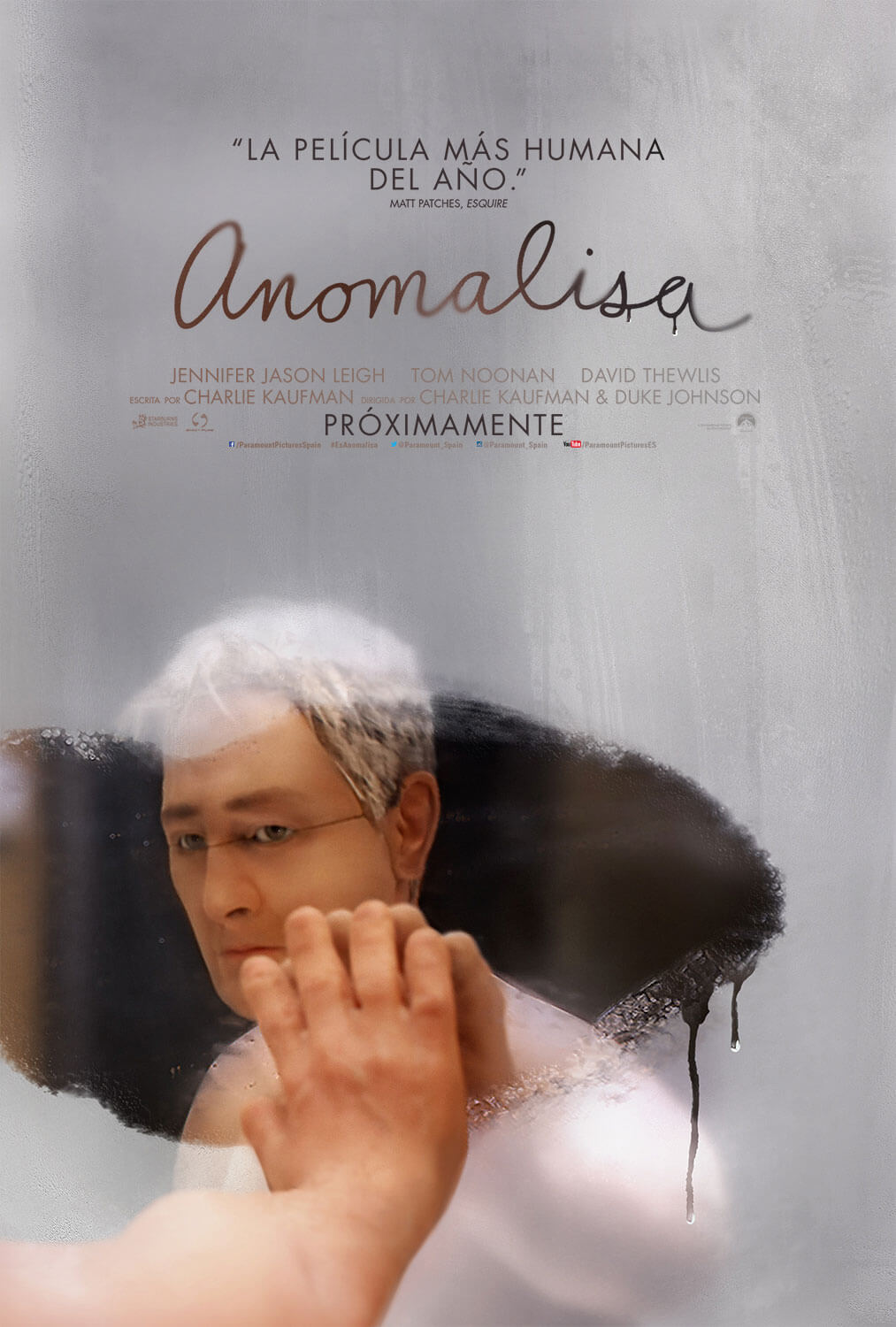

Anomalisa

By Brian Eggert |

Ever feel like you’re having the same conversation again and again but with different people? That identical conversation about the weather, the current cost of gasoline, or the performance of this or that sports team couldn’t be any less interesting. Or maybe it’s gotten so bad that these people don’t even seem different anymore. They’re all the same degree of dreary and uninteresting, homogenized by the same media and social blueprint. They even look the same now, their faces all but identical aside from some flourish in the hair or clothing. But then, all at once, an anomaly comes along, someone who doesn’t fit into the widespread normalization. There’s something indescribably different about them. Maybe it’s love at first sight; maybe it’s instant captivation. And as you’re impelled to get to know them better, it’s all very exciting and new. Until, of course, the experience fades gradually, and the new person in your life begins to sound and behave like everyone else.

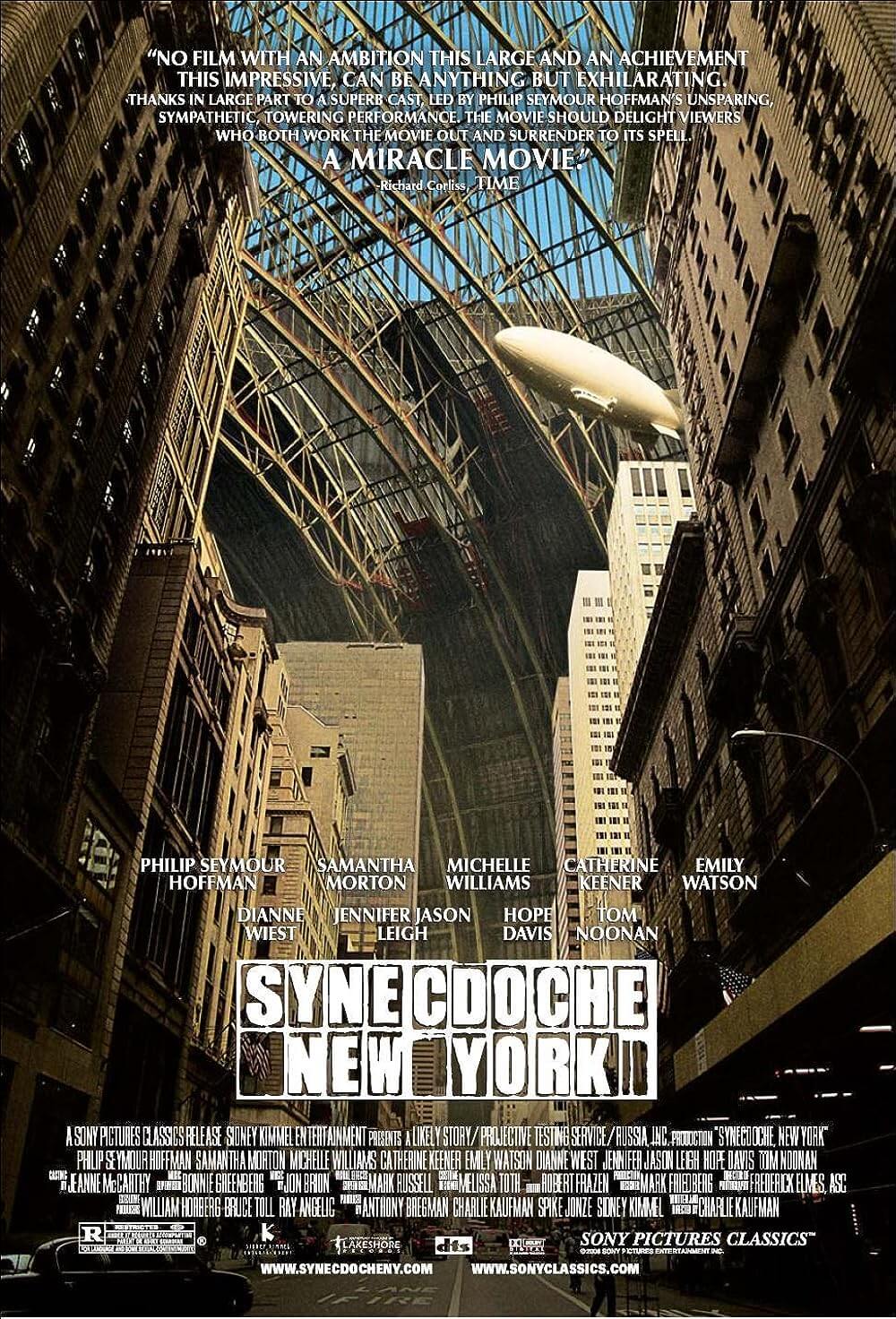

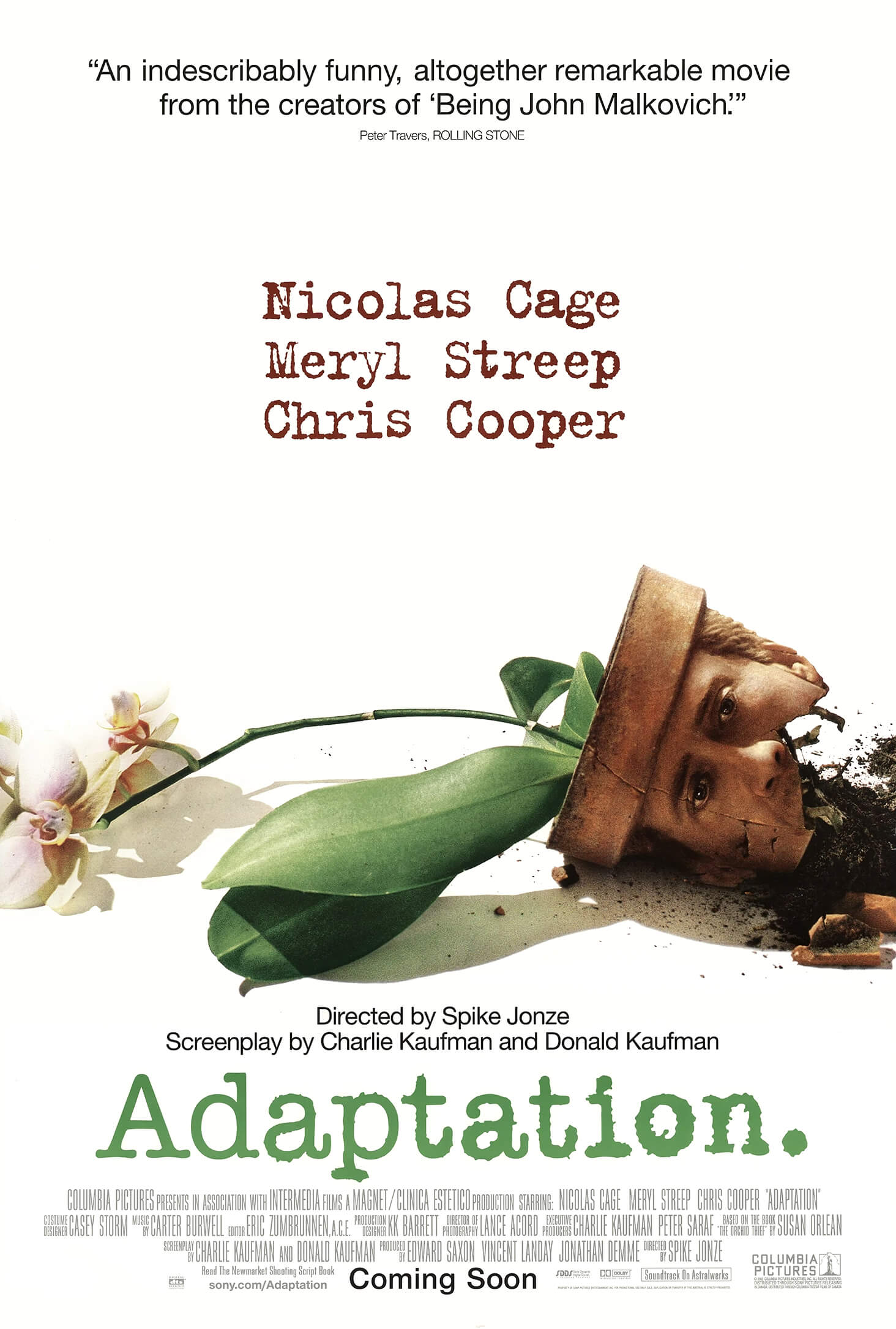

A story not unlike this one befalls the protagonist in Charlie Kaufman’s Anomalisa, only to the surreal and cerebral extreme audiences have come to expect from the screenwriter of Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, or his feature directing debut on Synecdoche, New York. By the time the protagonist of Anomalisa checks into a hotel called the Al Fregoli, it’s clear he may suffer from an extreme form of a disorder called “the Fregoli delusion”, in which a person believes that the people around them are all the same person in disguise. It’s just the kind of paranoid ailment we often see in a Kaufman character, whose deeply interior protagonists often have their inner fixations pouring out into reality. More often than not, his protagonists are artists yearning to be understood and loved, yet doomed to their own preoccupations and stubbornness—an evident reflection of Kaufman himself. In this, his second film, the protagonist is an average man, a champion of the mundane.

Kaufman originally wrote the story under the pseudonym Franco Fregoli, back when Anomalisa was performed as a stage play for composer Carter Burwell’s “Theater of the New Ear”. That experimental project was performed just twice in New York and Los Angeles. A successful Kickstarter campaign meant for a short film adaptation gave the production company the motivation required to finance Anomalisa into a full-length feature—a two-year endeavor, due to the unique process of stop-motion animation employed by Kaufman and Duke Johnson, the co-director. Johnson’s experience as an animator on Adult Swim’s claymation shows Moral Orel and Mary Shelley’s Frankenhole prepared him for the never-before-attempted challenge of animating Anomalisa with 3D-printed dolls. The result is strangely real, not unlike the marionettes from Being John Malkovich, except without the strings.

These figures appear with doleful human detail, including physical flaws and imperfections. And yet, Kaufman and Johnson made an intentional choice not to erase (with CGI) the visible seams on the characters’ faces, which are split across the eyes and nose between two plates: an upper plate for the eyes and forehead, and a lower plate for the nose, mouth, and jaw. Michael, the protagonist voiced by David Thewlis, has dark circles under his eyes and peppered grey hair. When the film opens, he’s on a plane to Cincinnati to speak at a conference about How May I Help You Help Them?—his book on customer service. A British man based in L.A., Michael is married with a young son. He’s also woefully unhappy, as we witness in his interactions with a fellow passenger on the flight, his cab driver, the hotel clerk, and bellhop. Each shares a conversation with Michael that is fascinatingly dull and immersed in oddly captivating minutiae, if only because the exchanges are slyly observed through Kaufman’s strange, off-kilter perspective.

These figures appear with doleful human detail, including physical flaws and imperfections. And yet, Kaufman and Johnson made an intentional choice not to erase (with CGI) the visible seams on the characters’ faces, which are split across the eyes and nose between two plates: an upper plate for the eyes and forehead, and a lower plate for the nose, mouth, and jaw. Michael, the protagonist voiced by David Thewlis, has dark circles under his eyes and peppered grey hair. When the film opens, he’s on a plane to Cincinnati to speak at a conference about How May I Help You Help Them?—his book on customer service. A British man based in L.A., Michael is married with a young son. He’s also woefully unhappy, as we witness in his interactions with a fellow passenger on the flight, his cab driver, the hotel clerk, and bellhop. Each shares a conversation with Michael that is fascinatingly dull and immersed in oddly captivating minutiae, if only because the exchanges are slyly observed through Kaufman’s strange, off-kilter perspective.

Another unique trait in a film that seems to overflow with them: The film’s voice work is limited to three performers, even though there are dozens of characters. Along with Thewlis and later Jennifer Jason Leigh, Tom Noonan supplies the voice of every other character: every background voice, every supporting character (including Michael’s wife and child), every insignificant role, even the vocals in the elevator music. By the time Michael arrives in his familiar, upscale hotel room, we’ve heard Noonan’s voice maybe thirty characters; moreover, we’ve seen an almost identical lower faceplate on each of these characters. As Michael settles in, he uses the toilet, orders room service, makes an obligatory call home, practices his speech, and watches a scene from My Man Godfrey (also animated) on television. All the while, he’s been thinking about Bella (Noonan once more), an old flame he left without explanation some 10 years ago. She lives in Cincinnati, so he calls her and invites her to his hotel lounge for a drink. As you might expect, Michael’s reunion does not go well. He’s left to go back to his room.

Clearly searching for something—answers, closure, or a tryst—Michael doesn’t know what he wants. But then he meets two women from a Midwest baking goods company; Lisa (voiced by Leigh) and her friend Emily (Noonan again) are in Cincinnati to attend Michael’s conference, and they consider him a celebrity. What’s strange is how Lisa’s voice cuts through the banality of normal conversation. She’s different and Michael isn’t sure why—he can hear the difference but cannot understand it. She’s an anomaly. Somewhat frumpy and with a scar on her right eye, Lisa is awkward and has low self-esteem. “Don’t you mean Emily?” she asks when, after the three share some drinks in the lounge, Michael invites her back to his room. He confirms that it’s Lisa he’s inviting, and to his room they go. They talk, have a drink, and break the ice when she sings Cindy Lauper’s “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” in a heartrending performance. And then they share the most realistic sex scene you may ever see in a film, performed by puppets or otherwise.

Plagued by a haunting nightmare that justifies the co-directors’ choice to leave the faceplate edge visible on their figures, Michael wakes up the next morning ready to abandon his life for Lisa, all because she sounds different than everyone else. But sure enough, because you should expect no less from a Kaufman film, as his introspective characters seem doomed to never find any measure of true happiness, something about Lisa changes for the worse. At a bittersweet breakfast the next morning, Michael begins to notice Lisa’s quirks and, all at once, she begins to sound like everyone else, like Noonan again. It’s a sad realization for both Michael and the viewer when this happens. Lisa remains sweet but oblivious, somehow ordinary. The dismal end to the brief reprieve that was Lisa also leads to Michael’s troubling, breakdown-of-a-speech at the customer service conference that’s almost shameful to watch. Burwell, a frequent collaborator with the Coen Brothers (who also took part the “Theater of the New Ear”), delivers a score for Anomalisa that is among his best, most wounded compositions.

Plagued by a haunting nightmare that justifies the co-directors’ choice to leave the faceplate edge visible on their figures, Michael wakes up the next morning ready to abandon his life for Lisa, all because she sounds different than everyone else. But sure enough, because you should expect no less from a Kaufman film, as his introspective characters seem doomed to never find any measure of true happiness, something about Lisa changes for the worse. At a bittersweet breakfast the next morning, Michael begins to notice Lisa’s quirks and, all at once, she begins to sound like everyone else, like Noonan again. It’s a sad realization for both Michael and the viewer when this happens. Lisa remains sweet but oblivious, somehow ordinary. The dismal end to the brief reprieve that was Lisa also leads to Michael’s troubling, breakdown-of-a-speech at the customer service conference that’s almost shameful to watch. Burwell, a frequent collaborator with the Coen Brothers (who also took part the “Theater of the New Ear”), delivers a score for Anomalisa that is among his best, most wounded compositions.

Watching and listening to the performances in Anomalisa is just as important as in a live-action film. Leigh’s lively, scratchy voice perfectly captures a sensitive, charming, but ultimately predictable personality. Thewlis is appropriately downtrodden, while Noonan’s various turns, from children to ex-girlfriends to the ever-present din in public spaces, contain his quiet intensity. It should be noted that Noonan played the actor who shadowed the director (Phillip Seymour Hoffmann) in Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York. Since Noonan usually plays weirdos and psychopaths, imagining a process where he voices such a wide range of characters adds a layer of intentional humor. Also by design, we must watch the careful animation, the body language, and expressive faces (at least, those of Michael and Lisa). Formally, this is unlike anything anyone has ever seen; it’s far beyond the reach of typical stop-motion animation studios like Aardman or Laika. But still, the animation has a shaky effect, like the adorable imperfection of Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox.

Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York was a film about a director who stages a production about his own life, complete with full city blocks and buildings to scale, with actors playing people he knows, sometimes playing themselves. Has Kaufman created a smaller-scale version of his own life? Perhaps. Set within a few simple yet perfectly detailed interiors, Kaufman’s eccentric little film is boundless in its weight, especially for those who share the writer’s melancholy, creativity, and yearning for something uncertain, but real. Anomalisa reminds those who can relate that life is more often than not a process of searching and disappointment. An aching lesson to be sure. It also shows us that a modest independent effort, budgeted at a mere $8 million and distributed in limited release by Paramount Pictures, can nonetheless achieve a perfect film through its creator’s clarity of vision. But Kaufman is less concerned about appealing to audiences than completing an intensely personal work of art. One suspects that the exact meaning of every detail, such as an antique Japanese doll Michael purchases at a “toy store” for his son, is known to Kaufman alone. All the same, those who give themselves over to Anomalisa will find a brilliant and profound look through Kaufman’s eyes, always a rare and exceptional experience.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review