American Ultra

By Brian Eggert |

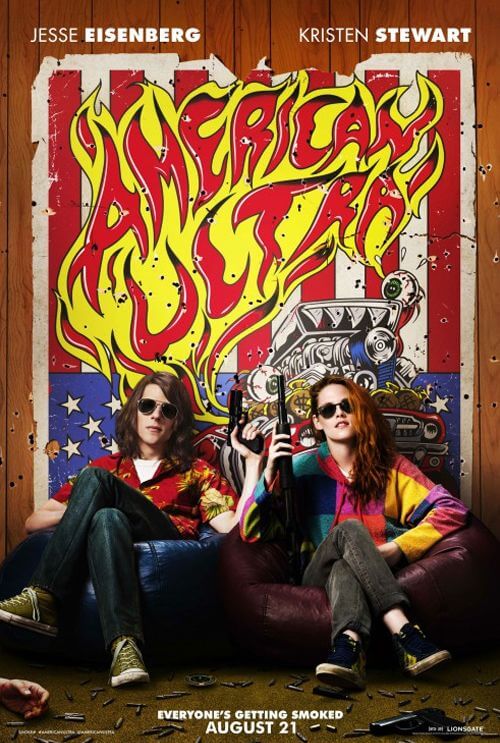

Never mind Jesse Eisenberg, Kristen Stewart, Topher Grace, and Walton Goggins. The real star of American Ultra is screenwriter Max Landis, son of John Landis (An American Werewolf in London). Landis achieves a rare kind of genre mash-up with American Ultra, similar to his work on Chronicle, the 2012 found-footage yarn about teenagers who find an alien rock and develop superpowers. Combining elements of a stoner comedy with a spy-themed actioner, the film was advertised all wrong, from drug-centric trailers to the hippy-dippy poster, placing emphasis on marijuana paraphernalia rather than the film’s similarities to the Jason Bourne franchise or The Manchurian Candidate. Once again, Landis has achieved something very familiar, yet very unique in its method of innovation.

Set in a forgotten Nowheresville, West Virginia, the story follows a pair of slackers-in-love. Mike (Eisenberg) copes with heavy anxiety and OCD issues, while also working at a convenience store and sketching out ideas for a graphic novel about a space ape. His girlfriend Phoebe (Stewart) helps him along and likewise copes with his issues. Unbeknownst to Mike, he’s actually the only working model of a failed CIA project, codenamed “Ultra”, to brainwash third-strike offenders into super-soldiers. When smarmy CIA jerk Yates (Grace) decides to take his own initiative and wipe out Mike, the only remaining evidence of the Ultra project, the project’s former administrator, the motherly Victoria (Connie Britton), resolves to activate Mike, so he’ll at least have a chance. What follows is a series of encounters where Eisenberg’s gangly and awkward physical stature becomes an unlikely source of badassery, as Mike takes down no end of CIA goons with moves that seem more reflex-based than logical.

Indeed, after each encounter, Mike nearly breaks down, unable to reconcile how he’s accomplished such bloody violence (the film earns its R-rating), while Phoebe, who knows more than she lets on, tries to keep him calm. Whether it’s the drugs or the anxiety, Mike’s not-all-there sensibilities lend plenty of humor along the way. For one, he begins to believe he’s a robot and, like a replicant out of Blade Runner, suddenly realizes he can’t remember his childhood. He also doesn’t behave as a super-spy might and doesn’t yet think like a trained killer. When an assassin chasing him yells “Hey,” Mike stops and turns as if to say, “Yes, what is it?” Then the assassin throws a grenade. Of course, Mike catches it and tosses it back. Boom.

Though the plot doesn’t offer many surprises and everything onscreen has happened in other films in some form or another, American Ultra excels at its treatment of its protagonists. Eisenberg and Stewart have a believable chemistry and romantic bond that drives the story. When Mike learns that Phoebe knew about his secret past and even played a part, his devastated reaction and her regret are heartbreaking. All at once, our concern shifts from Mike beating up government goons to hoping Mike and Phoebe can somehow repair their love. The supporting players, however, are handled with broader strokes. Grace’s over-the-top CIA villain sets the plot into motion for no reason whatsoever, except that he’s a monstrous a-hole. Yates’ top hitman, Laugher (Goggins), a former mental patient, has a tragic side too, but ultimately he’s just a psychotic baddie. John Leguizamo shows up as the paranoid drug-dealer Rose, and Tony Hale appears as Victoria’s devoted agent friend.

Do yourself a favor and ignore that the film’s director, Nima Nourizadeh, made only one other feature, Project X, a gross-out comedy populated by horny drunken dudes. Along with his talented, familiar-faced cast, Nourizadeh brings Landis’ screenplay to vivid life. There’s a wild intensity to Mike’s action scenes (director of photography Michael Bonvillain’s occasional shaky-cam notwithstanding), lending a tactile quality so every blow and gunshot are felt right in the gut. Several moments are visually inspired too, such as the sequence in Rose’s basement lit with black lights, fluorescent paintings, and mirrors. This scene could have been played for stoner laughs, but Landis understands that drugs and psychedelics aren’t what propel the story; and so, the scene becomes an existential moment leading into one of the film’s bigger revelations.

Despite mediocre reviews, a lousy box-office performance, and a poor marketing plan, American Ultra will probably become a cult-classic given time. Landis recently aired his frustration with moviegoers and Hollywood in general on social media. He suggested that an original story—that wasn’t a sequel, prequel, or otherwise part of an established franchise—had no chance at the box-office. Though his feelings on the subject are not without merit, the commercial failure of American Ultra probably has more to do with the distributors at Lionsgate not knowing how to effectively market the mash-up film. Once viewers realize the trippy posters are just the setup for a rather exciting, downright visceral, very often romantic, and unexpectedly fun experience, appreciation of the film will catch on. Hopefully.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review