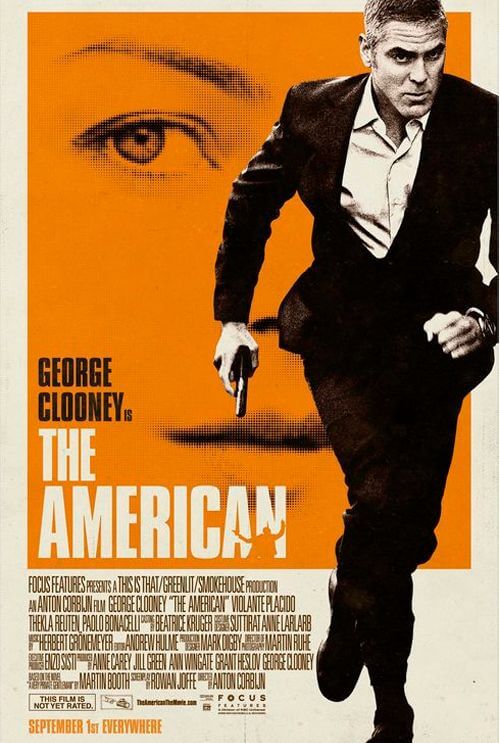

The American

By Brian Eggert |

Within the first moments of The American, it becomes apparent that its director, Dutch filmmaker Anton Corbijn, has versed himself in the cinema of French great Jean-Pierre Melville. The master of cool gangsters and narrative minimalism, Melville reformatted trenchcoat-laden criminals from Hollywood like those played by James Cagney and Paul Muni, giving them a poetic resonance and seriousness that helped define the artistic peak of European cinema of the 1960s. Attempting the same spare, methodically paced approach as Melville, Corbijn makes a fatal error by mistaking style for substance.

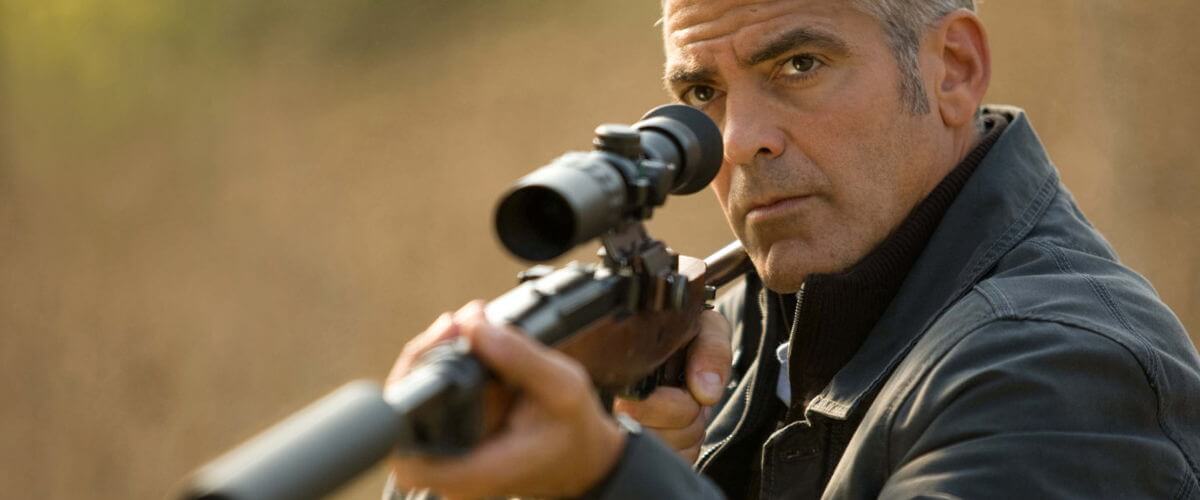

George Clooney plays Jack, a secreted man whose history, it seems, involves being a gun-for-hire. In the first scenes, his wintry getaway is interrupted by some Swedish assassins out to settle a score for who-knows-what. The film never explains why Swedish men are after him; it’s enough to know that his complicated past is catching up with him. When he arrives in Rome to shake his tail, he reports to his employer, Pavel (Johan Leysen), who tells him to lay low in a small Italian village. Of course, Pavel has a job for Jack to complete in the meantime. You see, Jack also specializes in constructing made-to-order weaponry from scratch for assassins, and Mathilde (Thekla Reuten) is such an assassin.

In the village, Jack meets a local priest, Father Benedetto (Paolo Bonacelli), who pesters him with questions of faith to which Jack has only cynical answers. But unlike the great character played by Alain Delon in Melville’s Le Samouraї—a comparable character study to be sure—Jack has no personal code that’s communicated within the film, therefore he has no real responses to the priest’s questioning. And if Jack does have a code, he must be breaking it by returning to Benedetto for company. He also visits a local whorehouse to meet Clara (Violante Placido), who instantly falls in love with Jack, despite his opaque disposition. Jack sees Clara as a possible companion with whom he can escape his solitary lifestyle. But no film forcing its fatalistic undercurrents as heavily as this one would dare allow for such a happy ending.

Clooney commands the screen, though his performance consists of largely grave expressions and brooding. Indeed, don’t expect the actor’s charming magnetism from the Ocean’s series, but rather a stripped-down version of his title role in Michael Clayton, except without the satisfying outbursts of emotion. The character Jack does little else than labor over building Mathilde’s weapon, keep fit, drink coffee, and visit his whore. However, there must be more to him. For example, on his back, there’s a butterfly tattoo and he admires butterflies in nature—this fact later is employed for a silly visual metaphor in the last shot. And regardless if there’s hardly a scene that doesn’t revolve around Clooney, the film fails to evoke much of anything in the viewer. The entire picture relies on Clooney’s characterization, but the script by Rowan Joffe, based on the novel A Very Private Gentleman by Martin Booth, offers nothing but atmosphere without feeling.

The staid mood is created via gorgeously framed photography by Martin Ruhe; each scene consists of a thousand beautiful stills. Filmed on location in Italy, the result also benefits from picturesque scenery. But clever compositions and an admirable look do not make up for the lifeless, unhurried quality of the story. Dialogue is sparse and to the point. Obligatory chase scenes and shootouts occur yet lack the thrills that would justify the high-octane marketing for this film. The finale is predictable, particularly for Melville aficionados. And overall, the film gives little sense as to who these characters are and why we should care.

Corbijn shows evident talent behind the camera in terms of visual style. He’s a former music video director for Depeche Mode and U2 and took iconic still photographs of musicians like David Bowie and Tom Waits. Yet this says nothing of his qualifications as a storyteller. He has almost no effect when it comes to involving his audience in The American, a story that amounts to a series of tired genre tropes strung together with the hope that their disposition will hide the film’s inability to make even a microscopic connection. Behind it all is the disservice to Jean-Pierre Melville, who deserves to have better films inspired by his work than this.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review