The Definitives

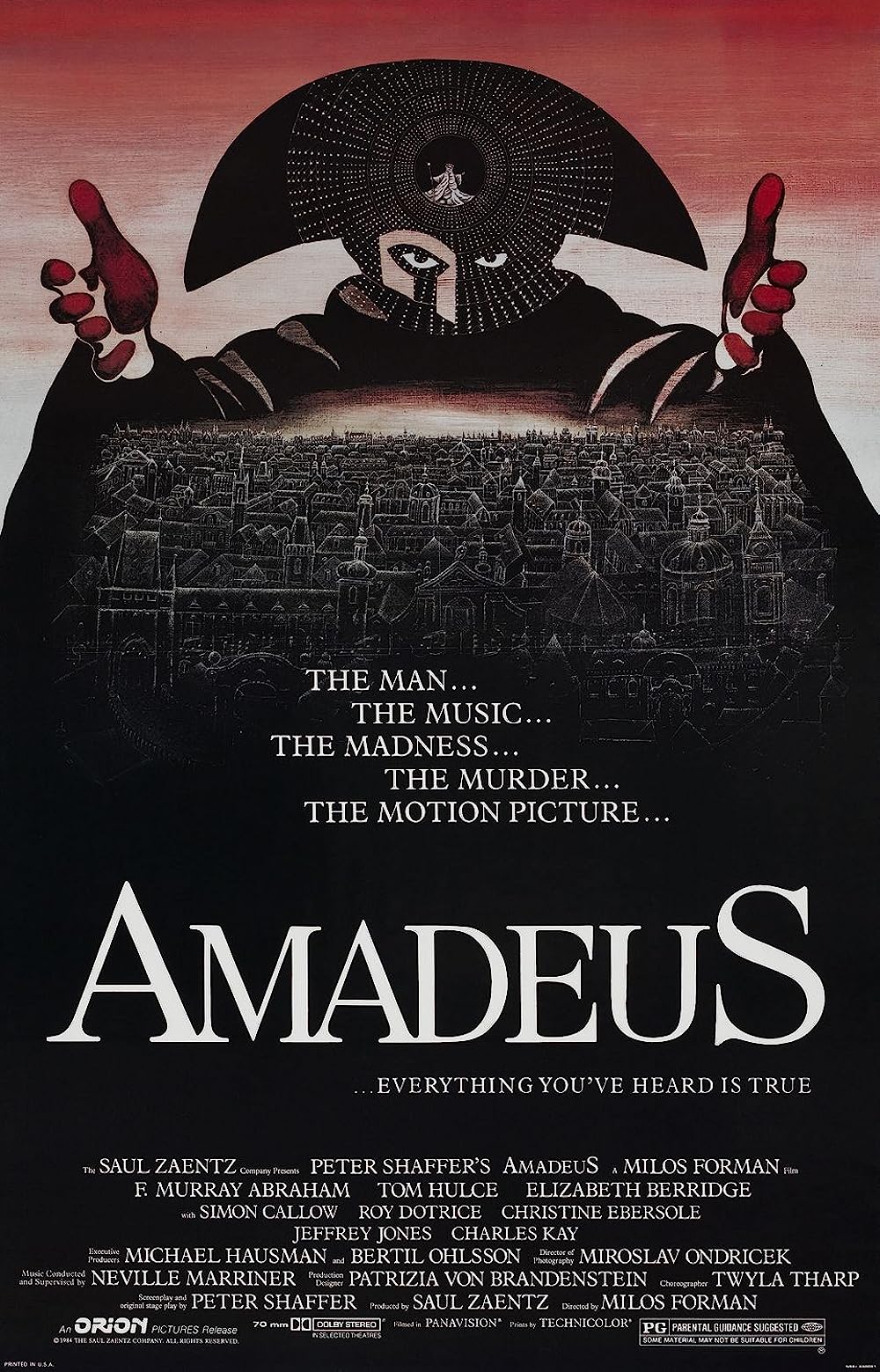

Amadeus

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In Latin, the name Amadeus means “love of God” or, in other words, the object of God’s adoration. How appropriate then that Peter Shaffer chose this name as the title of his 1979 stage play about Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, from which director Milos Forman and Shaffer elaborated into the 1984 film Amadeus. Told from the perspective of Antonio Salieri, the pious Venetian court composer who so desires God’s grace, the story comes from the vantage point of an unreliable narrator, a man so twisted by feelings of admiration and jealousy and betrayal that his perceptions distort history into a powerful, if subjective account. Despite the title, the film does not trace Mozart’s genius, rather the envy of Salieri, whose modest talent was such that he could not compete with his artistic rival, only appreciate the gift that God had chosen to bestow on someone else. As a historical biography, there are few motion pictures that take greater liberties with history; yet as a dramatic piece of cinema, there are few that match its splendors and delight.

Legendary independent producer Saul Zaentz, whose reputation for making “unfilmable” literary texts into award-winning films (such as Unbearable Lightness of Being and The English Patient), reteamed with his One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest director Forman on the production. Zaentz commissioned Shaffer to rewrite his play into a suitable script and, working closely with Forman, Shaffer developed his stage piece into a film that would require elaborate sets, staged productions of Mozart’s operas, and exclusive use of Mozart’s compositions almost as the film’s diegetic and non-diegetic music. From a film studio’s perspective, Zaentz and Forman’s period piece about an eighteenth-century classical composer did not arouse instant confidence, the subject being atypical box-office bait. And yet, something about Amadeus would draw considerable crowds and lead to it sweeping the 1985 Academy Awards with eight Oscars in all, including awards for Best Picture, Director, Adapted Screenplay, Costume Design, Art Direction, Makeup, Sound Mixing, and Actor (F. Murray Abraham). Perhaps audiences were and still are so struck by the film because it resolves not to attempt to understand the gift of incomparable talent, but rather to admire it from a distance with equal parts awe and resentment—a more relatable notion indeed.

Amadeus opens with a suicide attempt. In the 1820s, an aging Antonio Salieri (Abraham) slashes himself with a razor when his long-harbored guilt over causing the death of his idol, Mozart (Tom Hulce), becomes too much to bear. Restrained in an asylum, he offers his story as confession to a priest, setting his late, humble origins as a composer against Mozart’s emergence as a child prodigy. In 1781, Salieri, a Court Composer to Emperor Joseph II (Jeffrey Jones), followed Mozart’s career from a distance and stands in wonder of his gift—a gift so profound he deems that it could only be imparted by God. To this effect, Salieri has offered Him a life of chastity and abstinence so that, in exchange, he, too, might receive the talent to create music to appease the Almighty. Still, Salieri’s adequate skill and reputation is overshadowed, which is something Salieri seems inclined to accept until he first meets “The Creature”, as he later calls Mozart. A childish, philandering, scatologically obsessed jester with an absurd chortle, Mozart’s indecency in the face of his own God-given talent horrifies Salieri, who believes God has touched the wrong individual. At first, Salieri only questions God’s judgment, until Mozart’s moral deprivation—and Salieri’s resultant humiliation—becomes too much. Salieri decides to quiet God’s ill-chosen instrument by plotting Mozart’s ultimate ruin, even while he remains a devoted admirer.

Amadeus opens with a suicide attempt. In the 1820s, an aging Antonio Salieri (Abraham) slashes himself with a razor when his long-harbored guilt over causing the death of his idol, Mozart (Tom Hulce), becomes too much to bear. Restrained in an asylum, he offers his story as confession to a priest, setting his late, humble origins as a composer against Mozart’s emergence as a child prodigy. In 1781, Salieri, a Court Composer to Emperor Joseph II (Jeffrey Jones), followed Mozart’s career from a distance and stands in wonder of his gift—a gift so profound he deems that it could only be imparted by God. To this effect, Salieri has offered Him a life of chastity and abstinence so that, in exchange, he, too, might receive the talent to create music to appease the Almighty. Still, Salieri’s adequate skill and reputation is overshadowed, which is something Salieri seems inclined to accept until he first meets “The Creature”, as he later calls Mozart. A childish, philandering, scatologically obsessed jester with an absurd chortle, Mozart’s indecency in the face of his own God-given talent horrifies Salieri, who believes God has touched the wrong individual. At first, Salieri only questions God’s judgment, until Mozart’s moral deprivation—and Salieri’s resultant humiliation—becomes too much. Salieri decides to quiet God’s ill-chosen instrument by plotting Mozart’s ultimate ruin, even while he remains a devoted admirer.

Forman’s production relishes in extravagant details, enough to make the film a wonder of pure visual stimulation, even if that does not equate to historical accuracy. Larger-than-life powdered wigs and elaborate costume design by Theodor Pistek capture the ostentatious trends of the period, but also exaggerate styles present in eighteenth-century Vienna, while borrowing from French styles of the era perpetuated by Marie Antoinette, Joseph II’s sister. Cinematographer Miroslav Ondrícek shoots night scenes by candlelight, but with an amazing clarity and atmosphere. The production was filmed in Forman’s native Czechoslovakia, in Prague, where, unlike most now-modern European cities, the architecture retained the production’s desired centuries-old appearance. As a result, Forman’s crew was required to build few sets of their own (only one of Mozart’s opera houses, Mozart’s apartment, and a few other interiors), and location shooting was utilized for an unquestionable transportive quality. Prague’s Estates Theatre was used to film several opera scenes and was the actual location where Mozart premiered his operas Don Giovanni and La Clemenza di Tito in 1787 and 1791, respectively.

But from a historical standpoint, Shaffer’s script abandons strict detail to instead tell a compelling story with moments that may never have occurred but contain a pronounced drama. Biographical references to and characteristics of the film’s historical figures are exaggerated or altogether fabricated for their dramatic resonance, employing bits and pieces of historical fact or mystery as their source of inspiration. Consider how in the film Salieri uses his position to stop Mozart from acquiring a pupil—and thus a much-needed source of income for the talented but destitute composer—in the Princess of Württemberg. Historical record shows that Mozart applied for the position, but Salieri took the job instead, whereas the film puts forth that Salieri sat on the board that chose another composer entirely. In another subplot, it is suggested that singer Katerina Cavalieri (Christine Ebersole) has an affair with Mozart, though Salieri had long held affections for her but did not act upon them out of his chastity; historians have suggested that in all likelihood, Salieri, whose chastity was invented by Shaffer, no doubt bedded the singer. The greatest deviation comes from the detail which finds Salieri donning the black costume worn by Mozart’s disapproving father (Roy Dotrice) earlier in the film; Salieri appears at Mozart’s door and, terrifying Mozart with the notion of a ghostly reminiscence of his dead father, commissions a death mass. History suggests the obscure figure Count Franz von Walsegg, a minor composer, hired an anonymous garbed figure to commission Mozart’s Requiem Mass with the intention of passing it off as his own.

But from a historical standpoint, Shaffer’s script abandons strict detail to instead tell a compelling story with moments that may never have occurred but contain a pronounced drama. Biographical references to and characteristics of the film’s historical figures are exaggerated or altogether fabricated for their dramatic resonance, employing bits and pieces of historical fact or mystery as their source of inspiration. Consider how in the film Salieri uses his position to stop Mozart from acquiring a pupil—and thus a much-needed source of income for the talented but destitute composer—in the Princess of Württemberg. Historical record shows that Mozart applied for the position, but Salieri took the job instead, whereas the film puts forth that Salieri sat on the board that chose another composer entirely. In another subplot, it is suggested that singer Katerina Cavalieri (Christine Ebersole) has an affair with Mozart, though Salieri had long held affections for her but did not act upon them out of his chastity; historians have suggested that in all likelihood, Salieri, whose chastity was invented by Shaffer, no doubt bedded the singer. The greatest deviation comes from the detail which finds Salieri donning the black costume worn by Mozart’s disapproving father (Roy Dotrice) earlier in the film; Salieri appears at Mozart’s door and, terrifying Mozart with the notion of a ghostly reminiscence of his dead father, commissions a death mass. History suggests the obscure figure Count Franz von Walsegg, a minor composer, hired an anonymous garbed figure to commission Mozart’s Requiem Mass with the intention of passing it off as his own.

But these are just a few of the numerous, if negligible historical inconsistencies. Shaffer’s greatest deviations reside in his description of his titular character. Although evidence suggests Mozart’s sense of amusement was not above the scatological, surviving documents show nothing to determine that Mozart behaved as Hulce plays him—like a spoiled brat whose creative genius has been taken for granted, not because he is cruel or pitiless, but simply because it comes so easy to him. Contrary to the factually vague accounts which make reference to how “some woman” described Mozart’s laugh, there exists no concrete evidence that implies the composer actually laughed in the hilarious way performed—a staccato series of harsh, high-pitched bursts that begin like a clown riding a washboard and then ease off into a self-conscious sigh, a sound brilliantly developed by Hulce. Even a characteristic not so specific, such as how Mozart conducts his opera, is chosen for dramatic effect. Operas of the eighteenth century were not directed by a sole conductor standing front-and-center; rather, a concertmaster instructed the orchestra while a conductor was off to the side playing a fortepiano. Although toward the end of Amadeus, during a performance of The Magic Flute, Mozart is seen at a fortepiano, the majority of the film shows Mozart conducting the orchestra alone. Despite its inaccuracy, the film’s low-angle shot from the orchestra’s perspective, looking up at its conductor, has become an indelible one not only for this film, but to be repeated in any subsequent motion picture involving a classical or modern composer.

Pointing out these historical deviations is not to discredit Shaffer’s screenplay or Forman’s production, only enhance the viewer’s appreciation of how cleverly both men have manipulated history into a compelling story about the artistic process and its consequences. After all, Amadeus does not have an objective presentation told in the stodgy, timeline-following manner of most historical biopics. Instead, Shaffer chooses to create this melodrama through Salieri, who, by all accounts cannot be trusted to give us an accurate depiction of what really happened. In Salieri’s mind, perhaps Mozart laughs the way he does because Salieri finds the man absurd, an embarrassment to piety everywhere. Perhaps Mozart jumps up and down like an angry adolescent who wants a toy because Salieri sees him an ill-mannered whiz kid that never grew up. Mozart’s character has been so distorted by Salieri’s resentment that to bother with any kind of historical assessment of Amadeus equates to believing every word of an insane person, and in the final scene, Forman shows us how truly mad Salieri has become by placing him out among the lunatics. In the film’s last scene, Salieri is rolled out among them and he greets them with open arms, smiling, absolving them of their madness. And from this man we expect historical accuracy? Forman capture the chaos of Salieri’s nineteenth-century lunatic asylum recalls similar scenes of madness in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, scenes littered with naked, decrepit men running about, screaming obscenities and other nonsense, some shackled to the wall and others locked inside pens that in scale are smaller than a birdcage.

Pointing out these historical deviations is not to discredit Shaffer’s screenplay or Forman’s production, only enhance the viewer’s appreciation of how cleverly both men have manipulated history into a compelling story about the artistic process and its consequences. After all, Amadeus does not have an objective presentation told in the stodgy, timeline-following manner of most historical biopics. Instead, Shaffer chooses to create this melodrama through Salieri, who, by all accounts cannot be trusted to give us an accurate depiction of what really happened. In Salieri’s mind, perhaps Mozart laughs the way he does because Salieri finds the man absurd, an embarrassment to piety everywhere. Perhaps Mozart jumps up and down like an angry adolescent who wants a toy because Salieri sees him an ill-mannered whiz kid that never grew up. Mozart’s character has been so distorted by Salieri’s resentment that to bother with any kind of historical assessment of Amadeus equates to believing every word of an insane person, and in the final scene, Forman shows us how truly mad Salieri has become by placing him out among the lunatics. In the film’s last scene, Salieri is rolled out among them and he greets them with open arms, smiling, absolving them of their madness. And from this man we expect historical accuracy? Forman capture the chaos of Salieri’s nineteenth-century lunatic asylum recalls similar scenes of madness in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, scenes littered with naked, decrepit men running about, screaming obscenities and other nonsense, some shackled to the wall and others locked inside pens that in scale are smaller than a birdcage.

Abraham earns his Oscar by portraying Salieri as a man of painful inner conflict. Every smile has a double-meaning, a hidden hurt, as Salieri remains torn between his jealousy for Mozart and his wholehearted admiration of the genius’ music. But this character is torn in other ways as well. He prides himself for abstaining from women and drink, yet cannot help himself around sweets. Always at his desk or atop his instructing piano rests a dish of candy morsels. When Salieri first sees Mozart, he looks for someone who appears to have been venerated by God. While looking, he finds himself distracted by servants setting out a luxurious feast; he regards the spread and lets out a quiet moan of food ecstasy, and later sneaks into the room alone to steal a truffle. Salieri’s vice may not fall into gluttonous extremes, but in this single incidence he has given in to his own temptation. How duplicitous or simply self-unaware then that in his accounts to the priest, he portrays himself as an obedient servant of the Lord, completely oblivious to his own double standard and convenient condemnation of Mozart.

In 2002, Forman and Warner Bros. unveiled a “Director’s Cut” that restored 20 minutes to the original cut’s PG-rated runtime of 161 minutes. In the extended cut, we learn more about Salieri’s hypocrisy in the face of God in a reincorporated subplot. When Mozart’s wife, the equally unrefined yet comparably levelheaded Constanze (Elizabeth Berridge), appeals to Salieri to grant her irresponsible husband an instructing position for the Princess of Württemberg, Salieri responds by proposing that she secure Mozart’s position with a sexual encounter. Reluctantly, Constanze agrees and returns that evening to meet Salieri. She disrobes and stands before him topless; he regards her for a moment, and then calls on his servant to escort Constanze out. Such cruelty and humiliation underscores how perverse Salieri has become in seeking God’s approval, and later explains why she holds stern disapproval for Salieri when he helps Mozart on his deathbed, a point that was unclear in the original cut. (Incidentally, for this subplot, fuelled by shame and embarrassment rather than raw sexuality, Amadeus was unfortunately struck with an R-rating upon its re-release, reminding us why the MPAA earns their reputation as an inconsistent organization.)

In 2002, Forman and Warner Bros. unveiled a “Director’s Cut” that restored 20 minutes to the original cut’s PG-rated runtime of 161 minutes. In the extended cut, we learn more about Salieri’s hypocrisy in the face of God in a reincorporated subplot. When Mozart’s wife, the equally unrefined yet comparably levelheaded Constanze (Elizabeth Berridge), appeals to Salieri to grant her irresponsible husband an instructing position for the Princess of Württemberg, Salieri responds by proposing that she secure Mozart’s position with a sexual encounter. Reluctantly, Constanze agrees and returns that evening to meet Salieri. She disrobes and stands before him topless; he regards her for a moment, and then calls on his servant to escort Constanze out. Such cruelty and humiliation underscores how perverse Salieri has become in seeking God’s approval, and later explains why she holds stern disapproval for Salieri when he helps Mozart on his deathbed, a point that was unclear in the original cut. (Incidentally, for this subplot, fuelled by shame and embarrassment rather than raw sexuality, Amadeus was unfortunately struck with an R-rating upon its re-release, reminding us why the MPAA earns their reputation as an inconsistent organization.)

Just as Salieri’s view of himself is mutated, his reasoning of God’s desires range from tragic to disturbing, as shown on the young priest’s face. Played by Richard Frank, Father Vogler is Salieri’s sole audience member and listens as the raconteur weaves a sort of warped logic out of his misfortunes, all of which he blames on God. Mozart’s death gives way to the most powerful scene in Amadeus, which finds the composer suffering from exhaustion on his deathbed, and Salieri, who has tricked Mozart into writing a “death mass” so that he might steal it for himself and play it at Mozart’s funeral, offering to take dictation. As the story progresses, at times Vogler appears understanding and even enthralled by Salieri’s account; others, Salieri’s tale becomes unfortunate or tragic because, as Vogler’s face tells us, he believes so wholeheartedly that God controls all, that when his life goes awry, God becomes an unforgivable monster, cruel and mocking to such extremes that not even Vogler can defend. Vogler appears devastated and speechless in the final scenes, perhaps out of shock over Salieri’s murderous actions, perhaps from the misfortune that piety has brought forth. Faith has driven Salieri mad.

In one way or another, God’s influence equates to a form of internal madness, in which his presence results in something that occurs inside one’s head—be it the justification of a murder or artistic inspiration. Both Salieri and Mozart experience music in their mind, for example, and Forman plays that music for his audience so that we might understand the creative process. But consider how these scenes might look without the music. Early in the film, Father Vogler watches as Salieri demonstrates Mozart’s music on a piano, but then Salieri loses himself in the moment; his hands rise from the piano and begin orchestrating into the air, into nothingness, an expression of sheer elation on his face. Vogler looks on with what might be described as pity. But without the music to accompany this scene, the audience might be tempted to disregard Salieri’s testimony as that of a madman (or, at least, they would come to such a conclusion much earlier than they should). At the end of the film, when Mozart dictates lines of music for Requiem Mass in D Minor, Forman plays the composer’s progression of instruments and choir vocals as Mozart conceives them, Salieri struggling to keep up with his transcription as artistic inspiration unfolds before him. Hulce drifts in and out of his falsetto singing of the notes, his fingers twitching away to the tempo playing in his head. Mozart is driven by something, but is it the same authority that inspires Salieri to destroy the thing he admires most?

In one way or another, God’s influence equates to a form of internal madness, in which his presence results in something that occurs inside one’s head—be it the justification of a murder or artistic inspiration. Both Salieri and Mozart experience music in their mind, for example, and Forman plays that music for his audience so that we might understand the creative process. But consider how these scenes might look without the music. Early in the film, Father Vogler watches as Salieri demonstrates Mozart’s music on a piano, but then Salieri loses himself in the moment; his hands rise from the piano and begin orchestrating into the air, into nothingness, an expression of sheer elation on his face. Vogler looks on with what might be described as pity. But without the music to accompany this scene, the audience might be tempted to disregard Salieri’s testimony as that of a madman (or, at least, they would come to such a conclusion much earlier than they should). At the end of the film, when Mozart dictates lines of music for Requiem Mass in D Minor, Forman plays the composer’s progression of instruments and choir vocals as Mozart conceives them, Salieri struggling to keep up with his transcription as artistic inspiration unfolds before him. Hulce drifts in and out of his falsetto singing of the notes, his fingers twitching away to the tempo playing in his head. Mozart is driven by something, but is it the same authority that inspires Salieri to destroy the thing he admires most?

Of course, the music of Amadeus, nearly all Mozart’s and performed by England’s Academy of St. Martin in the Fields conducted by Sir Neville Marriner, raises the production, adding grandiosity to the drama and in turn enhancing the film into—in same cases literally—operatic realms. Several scenes are filled by on-stage performances in which diegetic music drives the moment. Most ingenious is how Forman and Shaffer carefully place Mozart’s music in non-diegetic ways to accompany scenes, selecting compositions to define not only a moment within the film’s dramatic structure but also to exhibit Mozart’s genius. When considering the alternative, such as an original motion picture score, there was no choice at all, really. The subject gives way to some of the best music ever written, and to not use that would be nothing short of foolish. At the 1985 Oscar ceremony, when Maurice Jarre won for A Passage to India, he quipped at how lucky he was that the music of Amadeus, not being an original score, could not be nominated.

Beyond the music, Amadeus transcends its narrative and even themes through its full embrace of pure filmmaking—sumptuous visual and aural pleasures, incredible performances, and grandly directed scenes over a haughty biographical analysis. Deeply cinematic flourishes in art design, magnificently ornamented sets and costumes, and the sheer dramatic profundity of what becomes a severe comic tragedy are marked by playful quirks in characters that live and breathe in spite of their sometimes ostentatious behavior. Mozart’s representation as an eighteenth-century rockstar transforms the material into something uniquely accessible and remarkably fun for a costume drama about a classical composer, as does Salieri’s destructive jealousy over Mozart’s brilliance. After all, have we not all wished that we could produce great art or perform a piece of inspired music as a true master? Like Salieri, we watch in bewilderment to grasp how unparalleled talent could come from such a buffoonish character. The film’s ongoing distinction between Mozart’s heavenly music and his juvenile behavior never ceases to charm or create a contrast that demands understanding for the creative process and the artist himself, lest we go mad.

Beyond the music, Amadeus transcends its narrative and even themes through its full embrace of pure filmmaking—sumptuous visual and aural pleasures, incredible performances, and grandly directed scenes over a haughty biographical analysis. Deeply cinematic flourishes in art design, magnificently ornamented sets and costumes, and the sheer dramatic profundity of what becomes a severe comic tragedy are marked by playful quirks in characters that live and breathe in spite of their sometimes ostentatious behavior. Mozart’s representation as an eighteenth-century rockstar transforms the material into something uniquely accessible and remarkably fun for a costume drama about a classical composer, as does Salieri’s destructive jealousy over Mozart’s brilliance. After all, have we not all wished that we could produce great art or perform a piece of inspired music as a true master? Like Salieri, we watch in bewilderment to grasp how unparalleled talent could come from such a buffoonish character. The film’s ongoing distinction between Mozart’s heavenly music and his juvenile behavior never ceases to charm or create a contrast that demands understanding for the creative process and the artist himself, lest we go mad.

Bibliography:

Abert, Hermann. W. A. Mozart. Cliff Eisen, Stewart Spencer (trans.). New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Holmes, Edward. The Life of Mozart. New York: Cosimo Classics, 2005.

Morton, Ray. Amadeus: Mozart on Film. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2001.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review