The Definitives

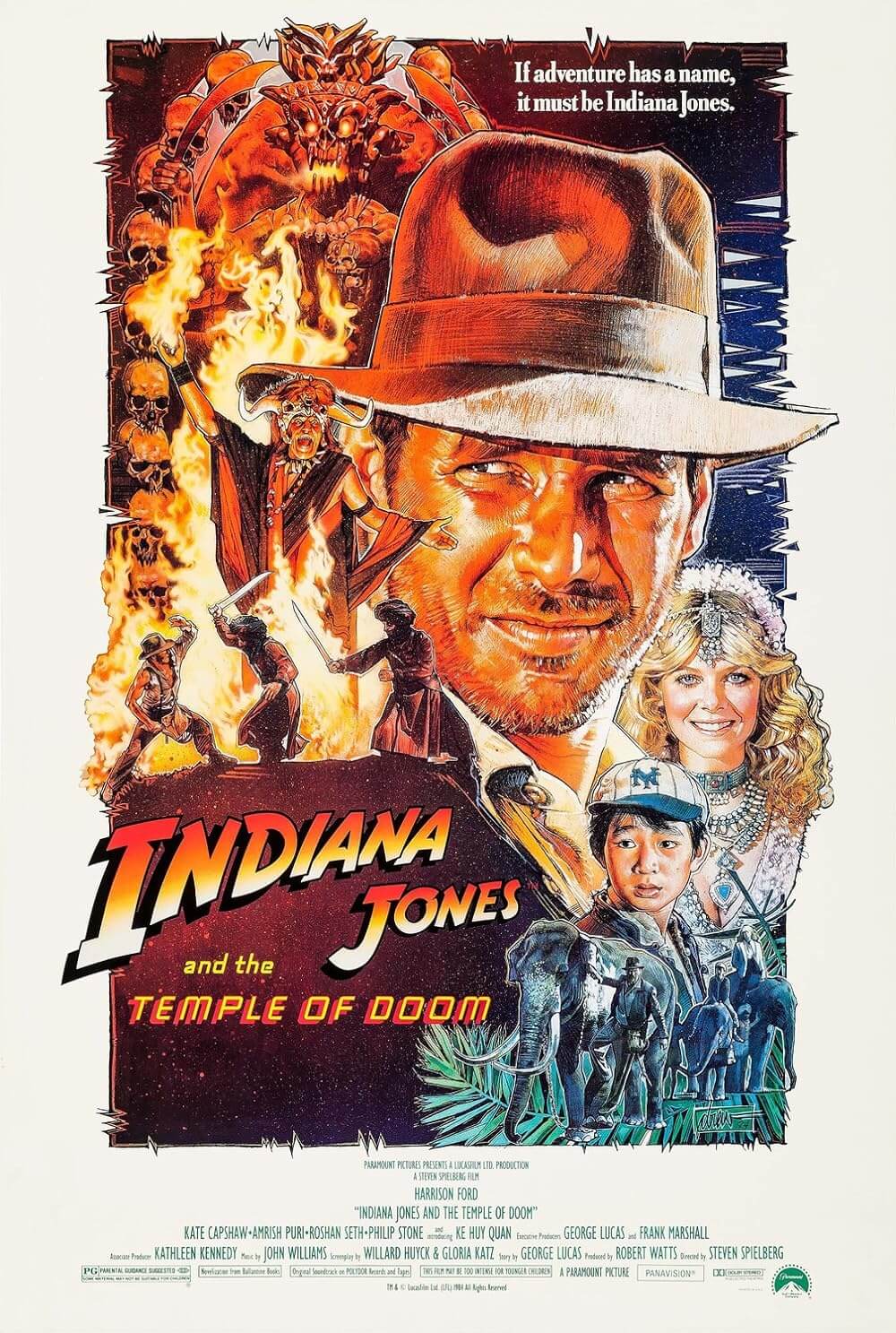

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom moves beyond simply replicating the adventure formula of its predecessor, Raiders of the Lost Ark. Instead, it takes Harrison Ford’s archeologist-adventurer hero Indiana Jones into another genre altogether, where the dangers are grim and the locales exotic. Whereas the 1981 original is comparably light and very often humorous, director Steven Spielberg and producer George Lucas deliver a sequel notoriously dark and violent, earning censures from both critics and audiences expecting a carbon copy of the first. They set aside Nazi villains and golden treasure common to classic Saturday adventure serials and incise their picture with a horror edge and chilling moments of suspense. The stakes feel higher, more foreboding. And these thrills offer less assurance that all will be well. Because of these dire changes in tone, the film would become something all involved felt they must apologize for. But no apology is required for an adventure tale that avoids the all-too-common Hollywood sequel mistake of repeating the same setups and stunts for an assured box office hit. The risks taken on Temple of Doom, though initially disparaged, delivered an incomparable escapist yarn nonetheless.

Narrative omissions notwithstanding, Spielberg polishes his 1984 production with his magic touch, bringing his audience to the edge of their seats and pulling them back to safety at the last possible moment. Again inspired by Saturday matinee serials and pulp magazines, the plot involves blood-drinking, zombie slaves, human sacrifice, and child slavery—certainly not themes contingent with family viewing. Spielberg captains us into the more frightening aspects of the franchise’s Golden Age origins, into a Heart of Darkness explored in glossies like Weird Tales and Oriental Stories. He surveys a world dripping with horror-based Orientalism and stereotypes not adhering to political correctness as much as a thematic exercise in kinetic and atmospheric aesthetics. But then, Indiana Jones’ world is one of pure adventure, fiction, escape, and, from a cinematic perspective anyway, not historical fact. For every frightening image and every suggestive depiction of Eastern culture, the film’s humor and energy integrate into an amalgamation of genre-spanning entertainment. Indeed, as Indiana Jones’ new love interest Willie Scott (Kate Capshaw) sings in the film’s opening scene (a Busby Berkeley-inspired song and dance number), “Anything goes!”

Consider Spielberg’s familiar uses of classic serial imagery, all enhanced through his blockbuster production: A room slowly grows smaller and smaller as the ceiling lowers and metal spikes emerge from above and below, the skeletons of past victims clinging to the metal points. A dizzying mine car chase sequence, complete with lava bubbling beneath the ramshackle rails, is possibly the only time in film history where the proverbial cinematic rollercoaster ride becomes as gripping as the real thing. An airplane escape piloted by the bad guys forces Indy to jump out with only a raft to soften the landing; he gently falls hundreds of feet to a cushioned landing, sleds down a snowy mountainside only to ride off the edge of a cliff, from which lands in white water rapids. A number of these sequences originated back during the pre-Raiders of the Lost Ark brainstorming sessions between Spielberg, producer George Lucas, and writer Lawrence Kasdan. Since the mostly desert and jungle locations of the first film barred the possibility of a life raft escape down a snowy mountainside, this stunt and others were set aside until the sequel—or prequel rather, since Temple of Doom takes place one year before the events in the original.

Consider Spielberg’s familiar uses of classic serial imagery, all enhanced through his blockbuster production: A room slowly grows smaller and smaller as the ceiling lowers and metal spikes emerge from above and below, the skeletons of past victims clinging to the metal points. A dizzying mine car chase sequence, complete with lava bubbling beneath the ramshackle rails, is possibly the only time in film history where the proverbial cinematic rollercoaster ride becomes as gripping as the real thing. An airplane escape piloted by the bad guys forces Indy to jump out with only a raft to soften the landing; he gently falls hundreds of feet to a cushioned landing, sleds down a snowy mountainside only to ride off the edge of a cliff, from which lands in white water rapids. A number of these sequences originated back during the pre-Raiders of the Lost Ark brainstorming sessions between Spielberg, producer George Lucas, and writer Lawrence Kasdan. Since the mostly desert and jungle locations of the first film barred the possibility of a life raft escape down a snowy mountainside, this stunt and others were set aside until the sequel—or prequel rather, since Temple of Doom takes place one year before the events in the original.

Temple of Doom is the most purely entertaining entry in the series because, as opposed to the first, the impenetrable nature of our hero Indiana Jones is questioned. At one point, Indiana is brainwashed by the film’s villains, making his otherwise assured victory questionable as he loses control of himself, striking his twelve-year-old sidekick Short Round (Ke Huy Quan). This is, of course, just another device in a succession of suspense devices, but it brings the audience closer to the brink than Indiana Jones has yet and will ever bring them. It becomes the only scene where we truly question our hero, and we’re all the more thrilled for it. More than any other film in this franchise, Temple of Doom plays with our moviegoer sense of safety, and perhaps this is why some audiences remain adverse to its particular brand of suspense—suspense requiring popcorn by the bucketload to appease these unrelenting cliffhangers, the oohs and ahhs of the production.

Lucas himself has suggested that because of his 1983 divorce, his temperament demanded a more sinister tone for this Indy prequel, matching the pointedly dark, artistically winning mood of the second entry in his Star Wars franchise. With The Empire Strikes Back, Lucas reached the series’ pinnacle by leaving his audience in limbo, displacing characters, and ending in tragedy; nevertheless, the picture struck gold with audiences and critics. In maintaining the breakneck Indiana Jones actioner speed, Lucas sought to interweave thematic darkness into this franchise, placing his MacGuffin (Sankara stones) into the hands of human-sacrificing Kali worshippers. Spielberg, too, had just ended his marriage, and though he voiced his concerns for the ominous departure (this coming from the same director who melted Nazi faces at the end of Raiders), in a way, the story appealed to him. Although his own signature style often capitalizes on happy endings and pointed optimism, Spielberg has on occasion explored intermittent departures like Schindler’s List, Minority Report, and Munich. But having previously explored a dour dystopian future in his debut feature THX 1138, Lucas found such territory artistically appealing and, at least given his turbulent personal life, familiar.

Having worked on both Raiders of the Lost Ark and The Empire Strikes Back, Kasdan was originally approached but refused to participate, finding the proposed storyline “mean-spirited” in its tone treatment of children. As an alternative, Lucas asked husband-and-wife writers Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz to tackle the script, given their mutual interest in Indian culture and mysticism from, among other sources, Kipling’s Gunga Din. Their story follows Harrison Ford’s Indiana Jones from Shanghai, where he barely escapes gangsters at Club Obi Wan, down a Himalayan mountain into India, and there commissioned by locals to retrieve a magical stone believed to sustain their village’s prosperity. Without it, their fields dry up, and people starve. Joined by Short Round (Ke Huy Quan) and the aforementioned, perpetually screaming nightclub damsel Willie Scott, Indiana ventures into the critter-filled jungle, finding a great terror awaiting his convoy at the home of the new adolescent Maharajah (Raj Singh). Inside Pankot Palace, remnants of an evil cult worshipping the goddess Kali revere her construction as a force drunk on the blood of her enemies, and they follow her example.

Having worked on both Raiders of the Lost Ark and The Empire Strikes Back, Kasdan was originally approached but refused to participate, finding the proposed storyline “mean-spirited” in its tone treatment of children. As an alternative, Lucas asked husband-and-wife writers Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz to tackle the script, given their mutual interest in Indian culture and mysticism from, among other sources, Kipling’s Gunga Din. Their story follows Harrison Ford’s Indiana Jones from Shanghai, where he barely escapes gangsters at Club Obi Wan, down a Himalayan mountain into India, and there commissioned by locals to retrieve a magical stone believed to sustain their village’s prosperity. Without it, their fields dry up, and people starve. Joined by Short Round (Ke Huy Quan) and the aforementioned, perpetually screaming nightclub damsel Willie Scott, Indiana ventures into the critter-filled jungle, finding a great terror awaiting his convoy at the home of the new adolescent Maharajah (Raj Singh). Inside Pankot Palace, remnants of an evil cult worshipping the goddess Kali revere her construction as a force drunk on the blood of her enemies, and they follow her example.

Within moments of arriving at Pankot Palace, Indiana’s troupe and indeed the audience are subject to some eyebrow-raising cultural representations, which, amid other factors, has earned Temple of Doom a divisive reputation. Consider the tongue-in-cheek dinner scene where throughout discussions of bleak Kali rumors surrounding the palace, Indy and other guests are served a smorgasbord of impossible foods: unborn baby pythons sucked down like spaghetti, beetle meat slurped from the shell-like an oyster, bloody eyeball soup, and for dessert—chilled monkey brains served still in the head. Certainly, audiences are not expected to believe all Hindus partake in such bizarre foods. And yet, scenes like this one are damned as blatant stereotypes. To be sure, it’s doubtful that Huyck and Katz, or any of the filmmakers, sought to represent India as a backward land filled with savages devouring inedible foods and soullessly forcing children into whip-driven labor; rather, these are Kali worshippers. Golden Age serials and adventure magazines used such gross exaggerations and misrepresentations to fuel their adventure appeal; Lucas and Spielberg simply follow that cue. This is fiction, after all, and escapist fiction to boot. Those who expect a history lesson be damned.

It would be too easy to condemn the production for describing one evil force, in whatever form it might take, as representing an entire ethnicity. That the filmmakers chose India reflects no cultural finger-pointing, simply an exotic backdrop for Indiana Jones to explore. Saturday matinee serials commonly found their hero penetrating some distant land, where foreign villains engage in absurd activities rarely based on fact. These accused images remain characterizations of evil, not an entire culture—or the barren Indian village our hero seeks to defend would not remain so pleasant, understanding, and peaceful. Nevertheless, after demanding to preview the script before shooting, the Indian government denied the production permission to shoot in their country, citing such problematic examples within the script. Spielberg moved his crew to Sri Lanka for exteriors laden with fruit bat skies and jungle landscapes. All interiors were flawlessly constructed in-studio with fiery lighting by cinematographer Douglas Slocombe and eye-popping production design by Elliot Scott. As a result of India’s concerns with the material, the film was banned temporarily upon its release—a ban lifted shortly thereafter, time healing any offended parties.

Critics pinned their disapprovals onto Temple of Doom’s lapel, balking at the overt violence permitted under an inappropriate PG rating. Spielberg initially defended the film, emphasizing “the picture is not called Temple of Roses, it is called Temple of Doom.” To be sure, the swastika symbolized inherent evil in Raiders of the Lost Ark, but evil could not be so effortlessly suggested with the largely conceptual Kali cult. No emblem would encapsulate them so singularly, and so, their atrocities must be shown. Indeed, with Nazis, our cultural awareness of their evil did not require a venture into Auschwitz to prove Indy was justified in fighting these bad guys. How else are we to understand the Kali cult’s strange brand of evil? We witness priest Mola Ram (Amrish Puri) reach into a victim’s chest cavity and remove the beating heart. The still-conscious human sacrifice is lowered into a lava pit where he burns alive; up above, the heart bursts into flames. Hyuck would later comment, “The audience must see evil, any kind of evil. You must show some of what that evil is in order to have a convincing fable. If anything, I feel it’s a problem with the ratings system, not with the movie.” Harrison Ford, too, initially defended the Indy prequel as an example of heroism, not evil, therefore acceptable for children. But all involved soon stopped defending their work, twisted their views to match the media’s, and began apologizing for the perceived problems with Temple of Doom.

Critics pinned their disapprovals onto Temple of Doom’s lapel, balking at the overt violence permitted under an inappropriate PG rating. Spielberg initially defended the film, emphasizing “the picture is not called Temple of Roses, it is called Temple of Doom.” To be sure, the swastika symbolized inherent evil in Raiders of the Lost Ark, but evil could not be so effortlessly suggested with the largely conceptual Kali cult. No emblem would encapsulate them so singularly, and so, their atrocities must be shown. Indeed, with Nazis, our cultural awareness of their evil did not require a venture into Auschwitz to prove Indy was justified in fighting these bad guys. How else are we to understand the Kali cult’s strange brand of evil? We witness priest Mola Ram (Amrish Puri) reach into a victim’s chest cavity and remove the beating heart. The still-conscious human sacrifice is lowered into a lava pit where he burns alive; up above, the heart bursts into flames. Hyuck would later comment, “The audience must see evil, any kind of evil. You must show some of what that evil is in order to have a convincing fable. If anything, I feel it’s a problem with the ratings system, not with the movie.” Harrison Ford, too, initially defended the Indy prequel as an example of heroism, not evil, therefore acceptable for children. But all involved soon stopped defending their work, twisted their views to match the media’s, and began apologizing for the perceived problems with Temple of Doom.

During the 1980s, a series of violent and scary PG-rated films, many of them produced by Spielberg, received scorn for being rated too leniently. For example, in 1982, Poltergeist, a film written and produced (and some say directed) by Spielberg and helmed by Tobe Hooper, the man behind The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, received a PG rating despite the presence of corpses and ghosts and children in peril. Gremlins, another film Spielberg produced with Joe Dante directing this time, was released a month after Temple of Doom and received positive reactions amid a sprinkling of harsh criticism from ratings hounds for the ineffective PG label, arguing children under pre-teen ages will find the material overly violent and too scary, and parents should have ample warning. Spielberg himself appealed to Motion Picture Association of America president Jack Valenti for a new category to circumvent disapproval of his future pictures, ushering in the PG-13 rating. By the end of 1984’s summer, Spielberg’s proposed new teen rating was already in force on John Milius’ Cold War paranoia effort Red Dawn.

Given the stigma surrounding the indisputable bloody content of this Indiana Jones prequel, we must reflect upon Raiders of the Lost Ark and ask: Was the original any different? Three years later, audiences seemed to forget about the thug chopped to bits by a propeller blade, a poisoned monkey, arrow-riddled bodies, a head with a spike run clear through, and a shockingly gory finale punctuated with melting Nazi faces and a Vichy Frenchman’s head exploding. This series comes riddled with violence furthering the danger involved in Indy’s eventual escape; without upping the ante, there is no risk, thus nothing to involve audiences. Scenes like the heart removal in Temple of Doom build suspense in the later sequence when Indy and Mola Ram struggle on the downed suspension bridge: We see the evil priests’ hand reach for our hero’s chest, causing us to wriggle in our seats, that graphic image of the removed heart branded on the brain. It’s among the most suspenseful, teeth-grinding scenes in the franchise.

Adventure stories are not intended to evoke feelings of comfort and safety but expel any such notion and dangle the audience over the proverbial pit. Indiana Jones’ exploits appeal to our Inner Child capable of suspending disbelief to ridiculous extremes, involving us in fantastical comic-book escapades. The inclusion of Short Round into the film’s hero base and enslaved children requiring rescue directly associates the viewer, as Spielberg’s narratives often do (see E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial or A.I. Artificial Intelligence), with children, who look up to and are eventually rescued by our savior Indiana Jones. The experience remains sharpened to a savage edge, perhaps too intense for young children, but wildly enjoyable blockbuster escapism nonetheless. Certainly, the MPAA rating of PG was far too moderate, but this is not an argument about the quality of the filmmaking, only the arbitrary third-party rating system. Spielberg’s production is one of his best, most thrilling, grandiose adventure epics. The film traps viewers inside the Temple of Doom, spending more than half the picture exploring the horrors within, shaking awake our slumbering Inner Child and scaring the hell out of it—all meant in good fun, of course.

Adventure stories are not intended to evoke feelings of comfort and safety but expel any such notion and dangle the audience over the proverbial pit. Indiana Jones’ exploits appeal to our Inner Child capable of suspending disbelief to ridiculous extremes, involving us in fantastical comic-book escapades. The inclusion of Short Round into the film’s hero base and enslaved children requiring rescue directly associates the viewer, as Spielberg’s narratives often do (see E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial or A.I. Artificial Intelligence), with children, who look up to and are eventually rescued by our savior Indiana Jones. The experience remains sharpened to a savage edge, perhaps too intense for young children, but wildly enjoyable blockbuster escapism nonetheless. Certainly, the MPAA rating of PG was far too moderate, but this is not an argument about the quality of the filmmaking, only the arbitrary third-party rating system. Spielberg’s production is one of his best, most thrilling, grandiose adventure epics. The film traps viewers inside the Temple of Doom, spending more than half the picture exploring the horrors within, shaking awake our slumbering Inner Child and scaring the hell out of it—all meant in good fun, of course.

In an interview with Premier magazine, Spielberg claimed he was eager to complete The Last Crusade to “apologize for the second one.” What is there to apologize for, one must ask? Or is it merely because a broken rating system failed to label this picture accurately, resulting in frightened children? The MPAA should have apologized, not Spielberg, who did nothing except make a wonderfully entertaining adventure. Or perhaps he apologized for trying something new with this darker tone than the first? Is it more believable that archeologist Dr. Jones engage in the same set of analogous circumstances over and over, or that he explores various cultures the world over? Whenever filmmakers follow a hugely successful property with a sequel or prequel, expectation becomes the film’s greatest enemy. Here, heavily publicized criticisms immediately following its release reside within the audience’s expectations and comparisons to the first and have little bearing on the quality of the production, superb special effects, or triumphant entertainment value. The film would earn nearly $180 million at the U.S. box office and earn an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects.

With the unfortunate poor reception of Temple of Doom, we must recognize that all adventures exist under the shadow of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Exceeding or even matching the original is an impossibility, except that Spielberg and Lucas intended to do neither, only to bring another kind of thrilling blockbuster to the screen, which they did to marvelous effect. A true wonder of Hollywood invention, unlike so many of its kind, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom is both great entertainment and great filmmaking. Often we can only expect one or the other. Despite recurrent criticisms for its innovations on the Indiana Jones tropes, we must look beyond and reflect upon the simplistic, uncomplicated joy of the action, the comic chemistry among the performers, and the unrelentingly feral activity represented onscreen. Never forget the Indiana Jones films’ theoretical foundation in diversionary amusement, and perhaps view this entry as the most dangerous and suspenseful of the lot. It is a film incapable of allowing its audience to be uninvolved, exposing us to consummate thrills and perils unequaled in the series, but with the same mastery of the adventure genre that only Spielberg can accomplish.

Bibliography:

Friedman, Lester D. Citizen Spielberg. University of Illinois Press, 2006.

McBride, Joseph. Steven Spielberg (Third Edition). Faber and Faber, 2012.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review