The Definitives

The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus

Essay by Brian Eggert |

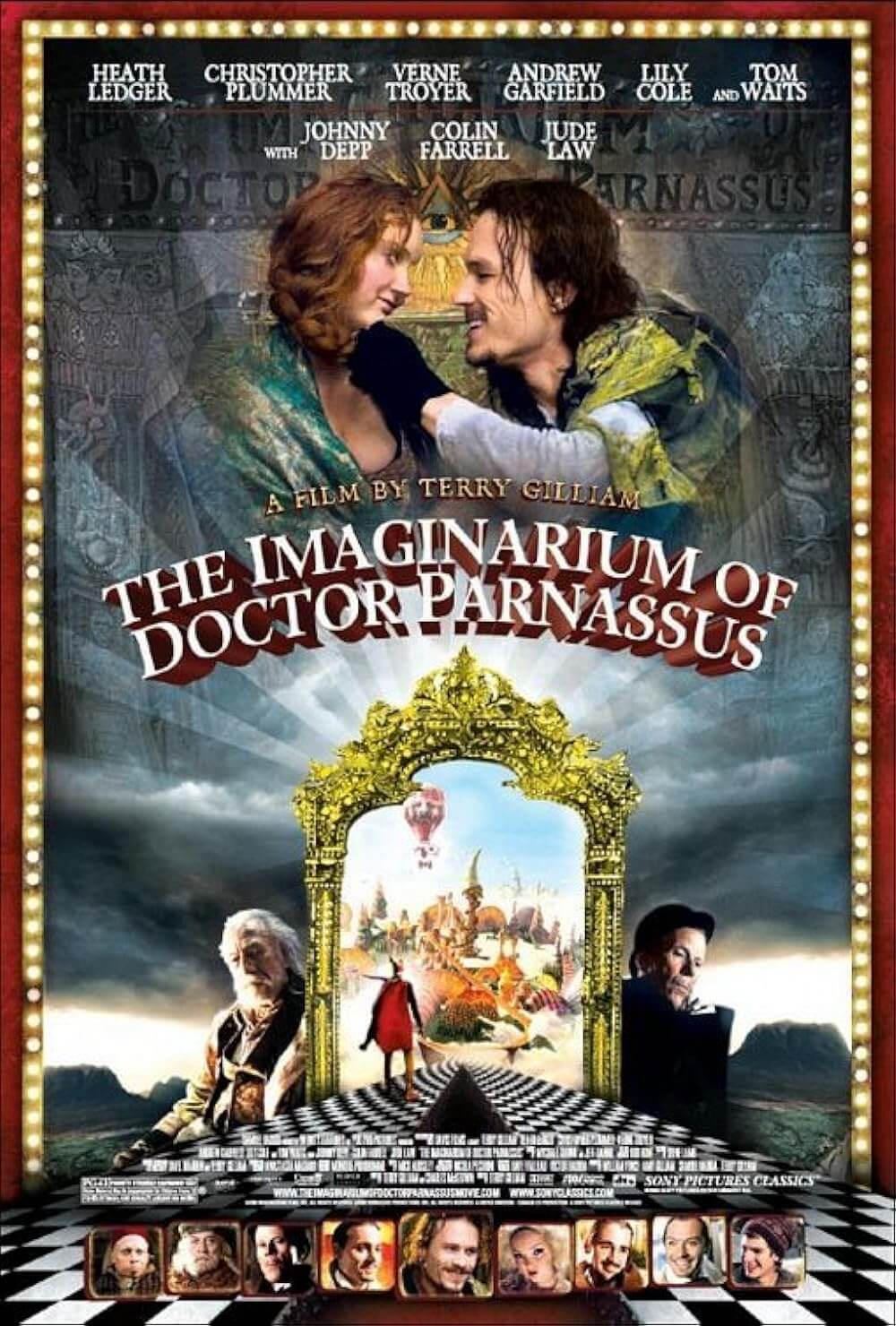

A three-ring circus of his own cinematic tropes, Terry Gilliam’s The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus reclaims and redefines the director’s reputation in the modern age, using a carnival of imagery rooted in the conflict between dreams and reality. Made with autobiographical flourishes, the film acknowledges through wild visual and narrative symbolism the monumentality of Gilliam’s filmmaking travails, how he has been all but crushed by those in power. But the completion of this film after the death of his star Heath Ledger represents a remarkable victory for Gilliam, when so often his productions have not survived such misfortunes. Through the story, Gilliam looks back upon his glory days and accepts the director he has become. While expressing his revulsion with the state of today’s film industry, he determines to continue putting his unreserved imagination into motion pictures, no matter the hardships, all through the guise of his narrative.

The narrative structure of The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus is one recognizably conceived by Gilliam and co-writer Charles McKeown, as the film strongly resembles their last collaboration from 1988, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. Both films leap back and forth between the humdrum complication of the real world and the effortless delight of an imaginary world, and both use the ramblings of a deteriorating, mystical old man as the vessel between the two. Through the narrative, a youthful character reinvigorates the old man otherwise forgotten by time, and in turn, validates his archaic attachment to storytelling and the fantastical. Both films resolve that storytelling and imagination breathe life into the world, and without them, the world becomes a bureaucratic nightmare.

This theme exists in Gilliam’s best films, namely those in his unofficial “Dream Trilogy”—three thematically linked pictures, each involving the relationship between fantasy and reality. Time Bandits reveled in the pure imagination of children; Brazil explored the necessity for escapism in a world wrapped in red tape; The Adventures of Baron Munchausen suggested that imagination was ageless. But every Gilliam film engages the dynamic of fantasy versus reality in some way: The Fisher King saw the world through the eyes of a damaged psyche and found things clearer, whereas the viewer was forced to sift through images in a deranged, time-traveling mind in 12 Monkeys. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas tried to grasp reality through the filter of heavy drug use, and Tideland through the skewed perspective of an uneven child. Gilliam’s directorial signature, though frenzied, has always been that of a spinner of dreams, a maestro of the enchanting and the majestic, while remaining ever the harsh critic of reality.

This theme exists in Gilliam’s best films, namely those in his unofficial “Dream Trilogy”—three thematically linked pictures, each involving the relationship between fantasy and reality. Time Bandits reveled in the pure imagination of children; Brazil explored the necessity for escapism in a world wrapped in red tape; The Adventures of Baron Munchausen suggested that imagination was ageless. But every Gilliam film engages the dynamic of fantasy versus reality in some way: The Fisher King saw the world through the eyes of a damaged psyche and found things clearer, whereas the viewer was forced to sift through images in a deranged, time-traveling mind in 12 Monkeys. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas tried to grasp reality through the filter of heavy drug use, and Tideland through the skewed perspective of an uneven child. Gilliam’s directorial signature, though frenzied, has always been that of a spinner of dreams, a maestro of the enchanting and the majestic, while remaining ever the harsh critic of reality.

In modern-day London, a ragtag troupe of performers, lead by 1,000-year-old immortal Dr. Parnassus (Christopher Plummer), opens their stage to all onlookers and participants of The Imaginarium. Those who enter through a magic mirror journey into the expansive imagination of the show’s eponymous Doctor; they face impossible imagery from both Parnassus’ unconscious, meditative mind, and their own imaginations. But ultimately their presence in The Imaginarium becomes a test to discover if participants can ignite their own imagination. Long ago, Parnassus made a deal with the Devil, named Mr. Nick (Tom Waits), for eternal life and access to the magic mirror. Partakers either embrace their imagination and emerge from the mirror reborn, or they lose their soul to Old Scratch, who tempts with a familiar, undemanding, and all-too-common escape. As the outside world becomes less and less the wondrous place it used to be, Parnassus watches as he loses more unimaginative souls to his opponent.

Weighing heavy on Parnassus’ shoulders, his daughter Valentina (Lily Cole) approaches the age of sixteen. Decades ago, Parnassus made a second deal with the Devil for a youthful appearance, so that he might court a beautiful lady; in return, on his firstborn daughter’s sixteenth birthday, she would belong to Mr. Nick. The conflicted Parnassus lives in a drunken stupor, barely able to perform in their road show, unable to tell Valentina about her inevitable fate. Meanwhile, the show’s sleight-of-hand expert Anton (Andrew Garfield) has fallen for Valentina, unaware that she was promised to Satan. Only Parnassus’ performer and confidante, Percy (Verne Troyer), knows of the looming contractual obligation. The show’s company, moving by carriage through the damp city, finds a stranger hanging by his neck from Blackfriars Bridge. They rescue him, finding a flute lodged in his throat to keep him breathing. When the man, played by Heath Ledger, awakens, he claims to have amnesia, though he sees a picture of himself on a newspaper and knows enough to conceal it from his rescuers. Parnassus learns the outsider’s name is Tony, and though the stranger offers to stay with the troupe and help modernize the show, the Doctor remains suspicious, believing him in the employ of the Devil. To be sure, ever the schemer, Mr. Nick insists Tony is not on his payroll. He even appeals to Parnassus’ sense of trepidation, offering him another wager to help Valentina escape her fate: If Parnassus can free five souls in The Imaginarium before Mr. Nick can corrupt five, then Valentina will go free.

Much to the chagrin of Anton, Valentia seems to be falling for Tony as he refurbishes the show, redesigning the façade in a contemporary form and changing its location to a better part of town. She dreams of what she believes is normality: an unexciting middle-class home in the suburbs, described by an advertisement in her trendy style magazine, the image complete with a dreamy husband and children. Such an existence is the antithesis of the troupe’s lifestyle, and it pains Anton to see her wish for something so synthetic. When the new show debuts, London’s elite is welcomed inside The Imaginarium, where Tony (now played by Johnny Depp) escorts one haughty woman on the correct path. She emerges renewed. Following her are three more women who enter and come out invigorated by the experience.

Much to the chagrin of Anton, Valentia seems to be falling for Tony as he refurbishes the show, redesigning the façade in a contemporary form and changing its location to a better part of town. She dreams of what she believes is normality: an unexciting middle-class home in the suburbs, described by an advertisement in her trendy style magazine, the image complete with a dreamy husband and children. Such an existence is the antithesis of the troupe’s lifestyle, and it pains Anton to see her wish for something so synthetic. When the new show debuts, London’s elite is welcomed inside The Imaginarium, where Tony (now played by Johnny Depp) escorts one haughty woman on the correct path. She emerges renewed. Following her are three more women who enter and come out invigorated by the experience.

The wager tilts in Parnassus’ favor until, all at once, four Russian gangsters spot Tony on stage. Recognizing them, Tony escapes inside The Imaginarium, where, now played by Jude Law, he sees himself as the successful entrepreneur he could have been, an innocent fleeing bad men. Of course, the Russians all fall sway to Mr. Nick’s temptations, leaving one soul left to determine the winner. Valentina opts to enter as the deciding soul, and Tony pursues after to stop her, as does Anton. The Imaginarium, always subject to the strongest imagination of those who enter, transforms into the horrible side of Tony (now played by Colin Farrell), the version of him wanted by authorities. Tony flees to save himself when his sordid past is uncovered, while Valentina decides to run away from her father finally, and in doing so, she loses her soul to The Devil.

In the final scenes, the unmasked Tony has been hanging once more, and Parnassus conceals his flute to assure the swindler will not survive another hanging. Mr. Nick mourns losing Valentina by gaining her soul, as he can hardly reap the benefits of her flesh in this condition. Time passes, and Parnassus’ traveling company has disbanded. One day, Parnassus, reduced to selling miniature puppet theaters, sees Valentina in a restaurant. Dressed so commonly with her apparent husband Anton and offspring, she is lost to The Devil, to a routine ordinariness void of imagination. And while Parnassus has lost touch with her, he continues to ignite the imaginations of his customers, however reduced from The Imaginarium his puppet theaters may be.

Gilliam admits that the story for The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus was conceived autobiographically, with the wildly inspired Parnassus serving as a reflection of the aging, increasingly obsolete, still dream-obsessed director. Just as Parnassus’ brand of traveling theater no longer appeals to modern audiences, Gilliam’s output has faced a progression of highly publicized trials. The director’s ongoing battle with Hollywood has led to a progression of troubled productions, climaxing with The Man Who Killed Don Quixote in 2003, a film that was plagued with problems until finally the production was altogether shut down. Since then, Gilliam has remained in directorial gloom, as demonstrated by the almost unwatchable, uncomfortable nature of his previous film, Tideland, arguably a picture that takes revenge of the very idea of Hollywood filmmaking. Curiously, the story of The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus acts as a mirror for Gilliam’s career, because just as Parnassus endures dangling on the brink, he ultimately comes out victorious in the end, if humbled. Similarly, while Gilliam has seen no end to his bad luck, he has fortuitously directed a film that reestablishes him as one of the most creative, original auteurs now working.

Gilliam admits that the story for The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus was conceived autobiographically, with the wildly inspired Parnassus serving as a reflection of the aging, increasingly obsolete, still dream-obsessed director. Just as Parnassus’ brand of traveling theater no longer appeals to modern audiences, Gilliam’s output has faced a progression of highly publicized trials. The director’s ongoing battle with Hollywood has led to a progression of troubled productions, climaxing with The Man Who Killed Don Quixote in 2003, a film that was plagued with problems until finally the production was altogether shut down. Since then, Gilliam has remained in directorial gloom, as demonstrated by the almost unwatchable, uncomfortable nature of his previous film, Tideland, arguably a picture that takes revenge of the very idea of Hollywood filmmaking. Curiously, the story of The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus acts as a mirror for Gilliam’s career, because just as Parnassus endures dangling on the brink, he ultimately comes out victorious in the end, if humbled. Similarly, while Gilliam has seen no end to his bad luck, he has fortuitously directed a film that reestablishes him as one of the most creative, original auteurs now working.

Production on The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus began in 2007 in London, where Gilliam had $30 million and a wonderful cast to play with. For the starring role, the director reteamed with Ledger, his lead actor from The Brothers Grimm. Ledger’s presence made the film possible, his Oscar-nominated status from Brokeback Mountain and the increasing buzz from his then-upcoming role as The Joker in The Dark Knight validating the considerable price tag on an otherwise small independent production. As shooting commenced over the next month, Gilliam captured the atmosphere of the city without dwelling on landmarks, using wide-angle lenses and his haphazard visual style. Almost all of Ledger’s scenes outside The Imaginarium were completed. Then, on a weekend reprieve in New York City, January 22, 2008, Ledger tragically died from an accidental prescription drug overdose. With the production in dire straits and investors threatening to withdraw, Gilliam’s worst nightmare, a repeat of what happened to The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, seemed likely. But Gilliam was determined to salvage the film, if for nothing else, to give audiences one last chance to see Ledger onscreen. Once Gilliam and McKeown retooled the script for Tony to become different versions of himself (represented by three actors) within Parnassus’ imagination, the whole production came together. Financial concerns disappeared when Ledger’s actor friends—Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell and Jude Law—offered to complete Ledger’s performance for no fee (or rather, the trio of stars donated their paychecks to Ledger’s daughter, Matilda, who was not yet in the late actor’s will). Still, just before post-production, the film’s producer William Vince died of cancer. And then Gilliam himself cracked a vertebra when he was hit by a car. But despite this string of extraordinarily bad luck, the film wrapped production. Gilliam rightly attributes its completion to mystic forces from beyond.

Given the low budget and parade of disastrous events to besiege the production, the easiest aspect of the film to trample upon are the special computer FX, which are limited to the ventures inside The Imaginarium—roughly one-fourth of the entire film. The animations cannot compare to those in tentpole franchises from major studios, but as they are reserved for ventures inside Parnassus’ mind, their unreal quality works within the story. Perhaps this was intentional, to render the dreamscape of Parnassus with a universal make-believe look; it would make logical sense, as those who enter Parnassus’ mind are aware that their surroundings are false—the dreams of a dreamer. Still, the film would have been a superior product had Gilliam rendered this world using the elaborate sets and tangible production design displayed on his earlier films.

Some critics have claimed that Gilliam altered his original script to include lines about a young talent expiring sooner than it should, making allusions to Ledger’s demise. Depp’s version of Tony says, “Nothing is permanent, not even death”—and this could be connected to the doubtless endurance of Ledger’s acting legend. The mistake that the film’s detractors have made, however, is confusing this Terry Gilliam film with a Heath Ledger film. Gilliam wrote the story to reflect his own life, even if the final product does end with “A Film by Heath Ledger and Friends.” Tony’s multiple personalities in the Imaginarium say nothing about Ledger; rather, they represent the two- or in this case the three-faced quality of Hollywood executives, for whom Gilliam has a strong disdain. Gilliam has said that Ledger’s character Tony represents a fictionalized version of Tony Blair, ever the politician trying to manipulate all sides to his advantage. After all, Tony bests not only Parnassus but The Devil too.

Some critics have claimed that Gilliam altered his original script to include lines about a young talent expiring sooner than it should, making allusions to Ledger’s demise. Depp’s version of Tony says, “Nothing is permanent, not even death”—and this could be connected to the doubtless endurance of Ledger’s acting legend. The mistake that the film’s detractors have made, however, is confusing this Terry Gilliam film with a Heath Ledger film. Gilliam wrote the story to reflect his own life, even if the final product does end with “A Film by Heath Ledger and Friends.” Tony’s multiple personalities in the Imaginarium say nothing about Ledger; rather, they represent the two- or in this case the three-faced quality of Hollywood executives, for whom Gilliam has a strong disdain. Gilliam has said that Ledger’s character Tony represents a fictionalized version of Tony Blair, ever the politician trying to manipulate all sides to his advantage. After all, Tony bests not only Parnassus but The Devil too.

With Gilliam being anti-authoritarian, he wrote the Tony role as a scathing look at someone whose wheeling and dealing has caught up with him. Inside The Imaginarium, Parnassus helps expose the various personalities behind such a character: the charming showman (Depp); the ambitious entrepreneur (Law); the manipulative swindler (Farrell). In Parnassus’ mind, Tony’s corruption is shown through Farrell’s role; he has borrowed funds from the Russian mafia to fund a charity for children and profited from it. When an adolescent boy, albeit with the face of Anton, threatens to expose him, Tony begins beating the child and reveals his true nature. Through Farrell’s interpretation of the character, Gilliam displays how he despises Tony—why else would Farrell’s face appear as the dreamy husband in Valentina’s modish magazine, if not to show the face of artificiality and illusion? Even the mysterious flute in Tony’s throat becomes a disturbing, Pied Piper-like symbol, as Tony hypnotizes those around him to follow his illusory song. Exposed as a selfish, duplicitous con artist, Tony is Gilliam’s enduring nemesis on and offscreen, and so the director’s sympathies unmistakably exist within Parnassus.

As much as The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus proves monumental for bringing audiences the last great performance of the late Heath Ledger, it does better to show the state of its director. Being a filmmaker who struggles to complete every film, Gilliam renders Parnassus in the same dilapidated state. Both preside over rickety productions that begin with something rundown and broken, but slowly blossom into beautiful works of magic, seemingly helter-skelter though they may be. Their presentations challenge their audiences, testing their resolve and their capacity to participate, but their audiences come out better for it. Still, after years of being spit upon or altogether defeated by The System, both Gilliam and Parnassus carry on.

Terry Gilliam is not the same director that he was twenty years ago. He has been unappreciated and all but forgotten by Hollywood, when at one time, specifically after his box-office success with Time Bandits, he was offered A-List projects and stood on the cusp of superstardom. But Gilliam has never sought mainstream approval, just the chance to tell the stories that he wants to tell. Consider the parallel of Gilliam’s now meager-budgeted films to Parnassus in the film’s final scenes, hunched over a puppet theater, exuding but a mere fraction of the glory he once had. There remains a look of satisfaction on Parnassus’ face, and we can imagine Gilliam quite satisfied with this film, a deeply personal work. Indeed, Gilliam is Parnassus.

Terry Gilliam is not the same director that he was twenty years ago. He has been unappreciated and all but forgotten by Hollywood, when at one time, specifically after his box-office success with Time Bandits, he was offered A-List projects and stood on the cusp of superstardom. But Gilliam has never sought mainstream approval, just the chance to tell the stories that he wants to tell. Consider the parallel of Gilliam’s now meager-budgeted films to Parnassus in the film’s final scenes, hunched over a puppet theater, exuding but a mere fraction of the glory he once had. There remains a look of satisfaction on Parnassus’ face, and we can imagine Gilliam quite satisfied with this film, a deeply personal work. Indeed, Gilliam is Parnassus.

Just as those who enter The Imaginarium may enter and miss its purpose entirely, losing themselves to Old Scratch, Gilliam’s audience runs the risk of being repelled by his overwhelmingly detailed design. His films require multiple viewings; the first time often results in sensory overload. It takes time and consideration to grasp the intended metaphors and small details piled into his narrative subtext and visuals. For some audiences, his films require too much participation to decode the controlled anarchy onscreen. Gilliam’s films are not effortless, but his work is that of a true original, an artist whose common narrative themes and brand of cinematic expression speak with deep resonance to an audience that “gets” his work more than a general one. With The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, Gilliam tells his audience that he has found peace with this truism about his films and his place in cinema, and through the story he declares, no matter what difficulties may arise, to keep mesmerizing us in the way only he can.

Bibliography:

Gilliam, Terry. Edited by Ian Christie. Gilliam on Gilliam. London; New York: Faber and Faber, c1999.

Mathews, Jack. The Battle of Brazil: The Nightmare Fantasy Making of the Movie. New York: Applause; Milwaukee, WI: Distributed by Hal Leonard Corp., 1998.

Yule, Andrew. Losing the Light: Terry Gilliam and the Munchausen Saga. New York, NY: Applause Books, c1991.

Support Deep Focus Review

Help keep independent film criticism alive by supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon. Since 2007, I’ve aimed to deliver critical analysis and in-depth reviews, free from outside influence. Your contribution not only gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, but it also helps me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong. If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways. Thank you for your readership!