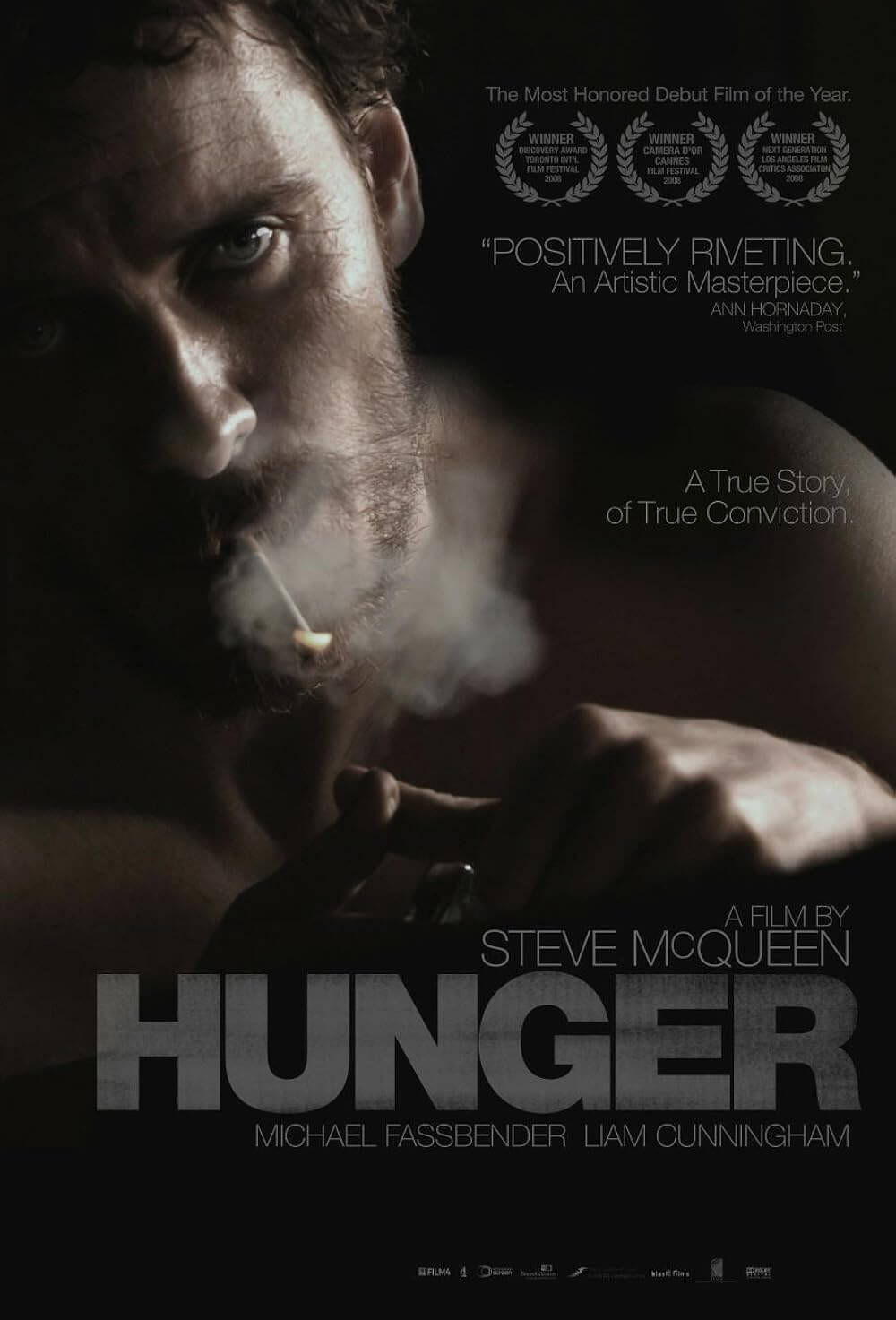

Hunger

By Brian Eggert |

Does self-sacrifice through protest make a martyr? Are figures like Christ and Gandhi considered great for their self-reliance under overpowering duress? And what of modern terrorists, who sacrifice themselves for a cause? Are they, too, worthy of celebration and idealization for dying for what they believe? Or does the specific reason matter? How far does martyrdom extend before the subject becomes no longer a hero but a victim of their own delusion and skewed beliefs? Hunger examines these questions by considering the death of Bobby Sands, the Provisional Irish Republican Army disciple arrested in 1977 for possession of a firearm, who in Long Kesh prison died after a 66-day hunger strike. Sands is played by Michael Fassbender, whose presence grows throughout the film, rendering an incredible if haunting physical transformation as his character dwindles away from self-imposed starvation. The performance is a small sensation, if only for the singular conviction portrayed therein.

During the days of ‘the Troubles’ between England and Northern Ireland, where the latter party fought for acknowledgment of their constitutional status, IRA members whose political agendas were ignored were labeled “criminals” and imprisoned. Hundreds found themselves damned to the H-Blocks, the British government ignoring their requests for Special Category Status—which would brand them not mere criminals but rather prisoners of war, thus granting them special rights under the Geneva Convention. And so, Sands leads a “dirty protest,” organizing his fellow inmates to reject the prison’s attempts at spiritual containment and fight back with the only means at their disposal. Excrement is spread over walls, covering them in a frantic array of smatterings like a base Pollack painting. Food is built like a dam on the inside of the cell door, so when the prisoners dump their urine within, it spills into the hallway. Maggots seem to crawl everywhere, infesting every scene, giving the viewer a necessary sense of isolation and uncleanness that will last long after the film is over.

Guards distribute their beatings, failing to regain order or feel retribution in the face of their immovable ideological enemy; however, the film suggests both sides are tired of the struggle but unwilling to back down. We see the drained prison guard Lohan (Stuart Graham), his bloodied knuckles and weary brow, and along with the frightened-yet-determined rookie prisoners like Gerry (Liam McMahon), humanity finds an exhausted home on all of their faces. The horrifying degrees to which these men go to support their cause is equally commendable and deplorable; how far the scale tips to one side or the other is up to you.

First-time director Steve McQueen creates a sparse sequence of events that ultimately boils down to a few key scenes. His picture is comprised of pensive takes looming over the prison’s horrid conditions. The long stationary shot down the cell hallway, where an attendant in a sanitation suit disinfects and wipes away the many puddles of urine, presents a harsh reality. The dialogue remains unimportant next to absorbing the setting and its circumstances, though when McQueen chooses to show conversation, every line bears significance. Consider the film’s unbroken 17-minute shot of the face-to-face between Sands and Father Moran (Liam Cunningham), where Sands attempts to justify his decision to ultimately starve to death for his cause. McQueen leaves his camera unmoved for a record amount of time, concentrating on the two throughout their weighty debate. Such a simplistic take speaks to the focused and determined direction, which cares more about the audience’s ideas than its own.

Like The Escapist, another import from the United Kingdom by IFC Films, Hunger makes incredible use of a prison setting for a powerful drama. Every prison movie has its own ideas of detention and freedom, but here McQueen, who also co-wrote the film along with Edna Walsh, leaves the viewer in a neutral state open for later rumination. And in differentiating itself by involving the viewer on a profound level, the film forces reflection and appreciation. Sands may be seen as a hero or a madman for his actions, but your inevitable heated discussions on the matter are what this film hopes to ignite.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review