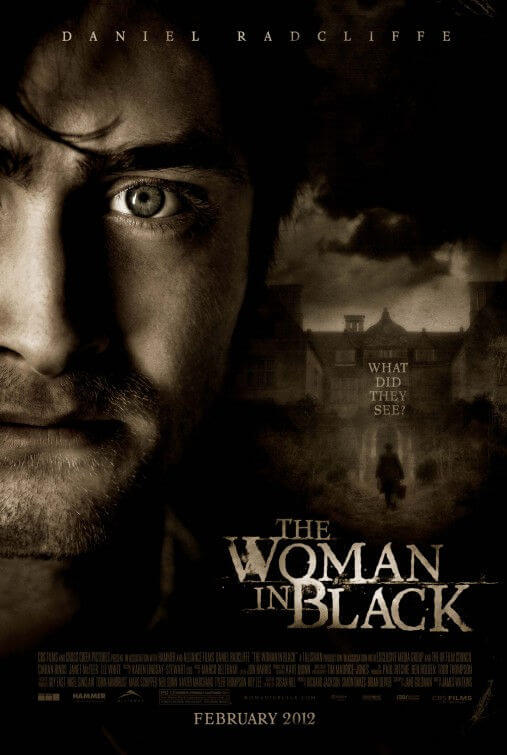

The Woman in Black

By Brian Eggert |

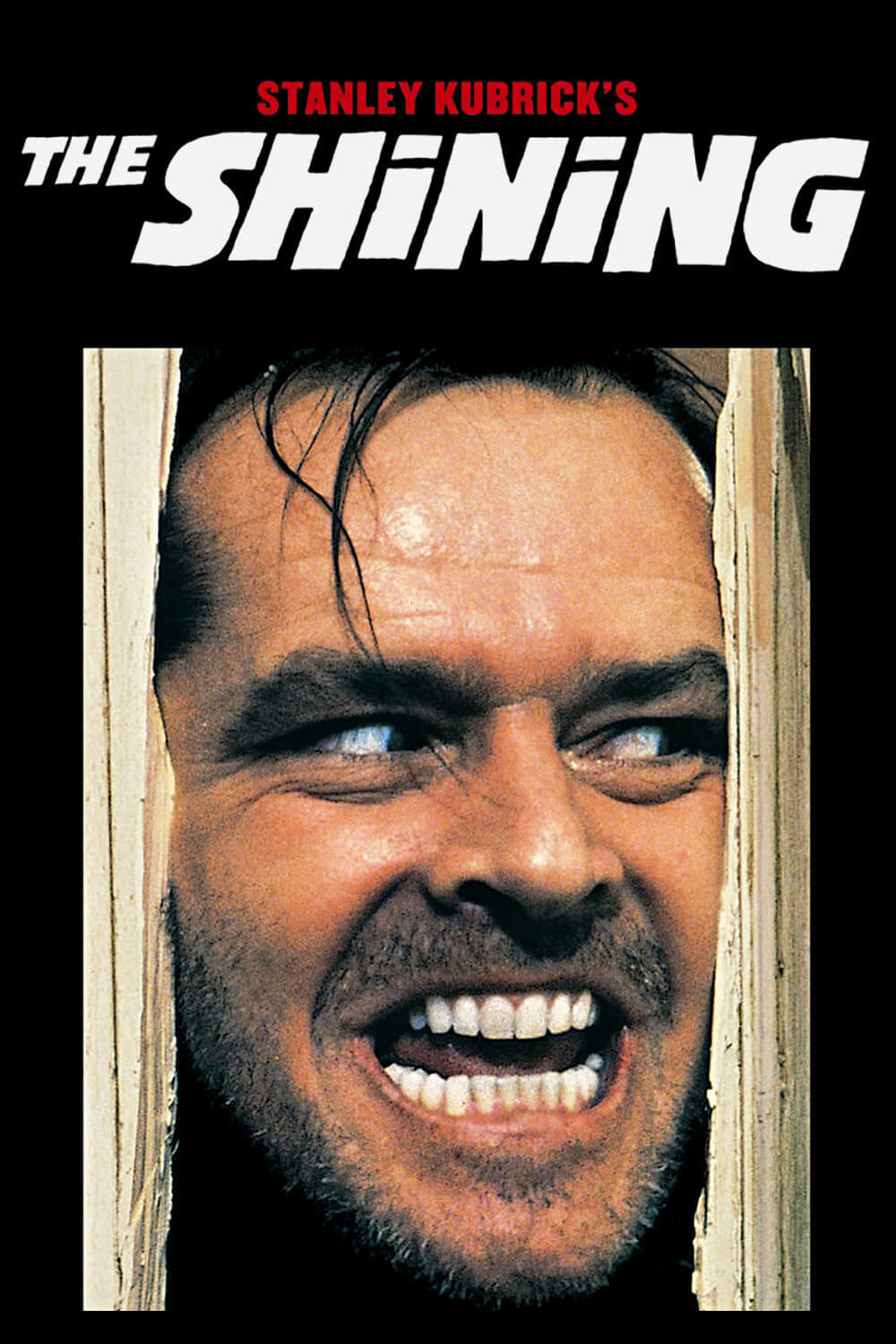

For horror aficionados, the prospect of a new Hammer Film Productions release is a major occasion. Hammer hasn’t distributed a film that was shot in England for about forty years, but in their heyday, they were responsible for bloody, pointedly British versions of classic tales of terror—such as The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), which habitually starred Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. In The Woman in Black, Hammer’s revision of Susan Hill’s oft-adapted gothic ghost story, the production contains an attractive Victorian backdrop and a chilly atmosphere that endeavor to give its audience the creeps. But the filmmakers rely far too much on common ghost story mechanics to propel the plot, leaving the audience to compare the result to better examples (such as Insidious or The Orphanage) from the same genre.

Daniel Radcliffe retires his wizard garb to play Arthur Kipps, a widower caught in a four-year bout of despair after his wife died during childbirth. In danger of losing his job at his law firm, he’s asked to redeem his recent detachment by setting out from London to a remote village where he’s to resolve the estate of a client who has just died. Once there, a foreboding mood sets in as Kipps receives suspicious looks from the townspeople, none of whom want him to stay or visit the Eel Marsh House, which rests on a plot of land cut off from the world at high tide. Everyone seems to be hiding a secret, and somehow it involves dead children and a phantom that no one will speak of. Only a wealthy realist named Daily (Ciarán Hinds) will talk to Kipps, but even Daily has his secrets, as alluded to by the deranged behavior of his wife (Janet McTeer). As the story progresses, Kipps finds himself rummaging through the oddly dilapidated house of the recently deceased, finding clues to a mystery that soon haunts him as well.

Screenwriter Jane Goldman (Stardust and X-Men: First Class) and director James Watkins (the uncomfortable Eden Lake) use every trick in the ghost storybook to elicit scares. A rickety rocking chair, an abundance of dust and cobwebs, shadows that appear and abruptly disappear, decrepit porcelain dolls, phantom silhouettes, shifty-eyed townspeople, a grave excavation, and creepy wind-up toys with murderous faces that play peculiar tunes—they’re all in attendance. These familiar horror objects and attributes are enhanced by the century-old setting, period costumes, and somber tone of the film. However clichéd, such details are effective until Watkins employs distracting CGI fog in an attempt to create ambiance. Alas, it’s an obviously animated trick that looks annoyingly out of place in this setting. I ask you, would it have been so much trouble to simply turn on a few fog machines? “Real” fake fog was wonderfully effective in Hammer’s early films, and it would’ve been here too.

Although previous adaptations of Hill’s story have been cheesy, albeit watchable, this version comes with more post-J-horror-remake flourishes than classic scares. Even the title character—the shadowy, inexplicably screaming specter haunting Kipps throughout the film—looks suspiciously like one of the spirit things from The Grudge or The Ring. Her presence is joined by a collective of creepily motionless dead children staring and occasionally scampering for effect. Together, they create no end of unexplained noises and shadows for Kipps to follow. In what felt like a never-ending sequence mid-film, Kipps wanders through the darkened house, his way barely lit by candlelight, pursuing whatever curious sight or sound it pleases him to investigate. As he looks into each apparition, the scene ends with a predictable jolt; Watkins, meanwhile, places ghostly shapes barely seen in mirrors and windows for a Did I just see that? effect.

By the end, when Goldman’s loose adaptation heads into hokey M. Night Shyamalan territory, it becomes abundantly clear that The Woman in Black is more inspired by the likes of The Sixth Sense and The Others than the gothic stories that occupied the Hammer productions of yesteryear. Take away the era’s costumes and the attractive locomotive sequences, and you have yourself another disposable supernatural chiller like the handful released by Hollywood each year (and not a particularly engaging one at that). Radcliffe does his best with what he’s given; he delivers a two-dimensional character, just as Hinds adds another layer to his role by his commanding presence alone. But overall, Watkins’ capable use of atmospherics doesn’t amount to a ghost story of substance or even, at the very least, satisfying shocks.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review