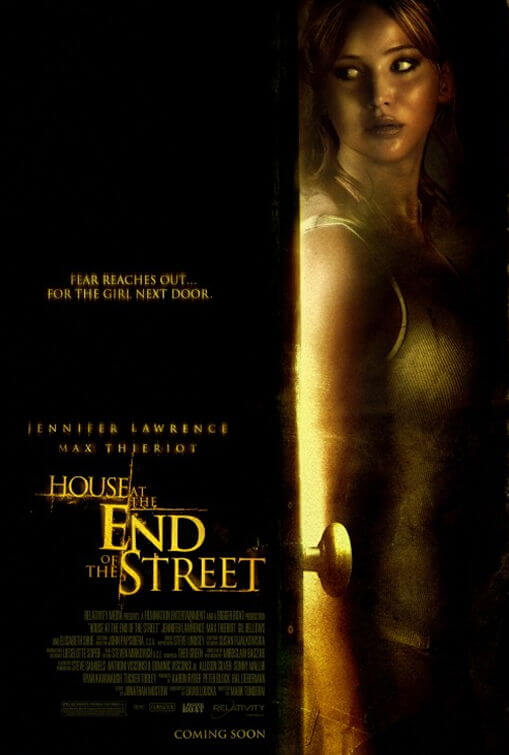

House at the End of the Street

By Brian Eggert |

House at the End of the Street is the worst kind of derivative horror, in which every element that wasn’t stolen from better movies feels banal and formulaic. Written by David Loucka, who forced the preposterous Dream House on moviegoers last year, the movie proceeds with a mechanical plot about a rebellious teenage girl who’s drawn to the mysterious boy next door, only to discover he’s harboring a dark secret in his basement. From the madhouse prologue to its predictable twists and turns, the movie pilfers unsparingly from Hitchcock’s Psycho. Jennifer Lawrence stars, having shot the movie in 2010 before the popularity following her Oscar nomination for Winter’s Bone and her headlining the blockbuster franchise The Hunger Games made her into a bankable star. One expects that had she received this script after her nomination, her agent would have tossed it in the garbage where it belongs.

Lawrence plays Elissa, who has just moved to a new town with her recently divorced, former wild child mom, Sarah (Elizabeth Shue). They’re renting an enormous house in an upper-middle-class neighborhood, but the rent is cheap because the house resides next to the site of a murder. Next door, as we learn in the prologue, two parents were killed by their brain-damaged daughter, who disappeared after her crime and was assumed to have drowned. Now the killer’s older brother, Ryan (Max Thieriot), lives alone in the house, while the town’s urban legend claims his sister Carrie-Anne (Eva Link) roams the surrounding forest. Sarah remains suspicious of Ryan, a quiet, introverted loner to whom Elissa is drawn. She pursues a romance with him against the wishes of her mother, even though local cop Weaver (Gil Bellows) insists Ryan is just misunderstood.

Meanwhile, Ryan is persecuted by the narrow-minded townspeople who’ve never forgiven his family for inadvertently causing their property values to drop. One bully, schoolmate, and future date rapist Tyler (Nolan Gerard Funk), unleashes an unprovoked violent tirade against Ryan. But we know better than to feel sorry for him. Director Mark Tonderai eventually takes us into Ryan’s house, down into his basement, where he’s keeping Carrie-Ann locked up and sedated in a storage room. Of course, this isn’t the only secret the filmmakers have up their sleeves, but none of the subsequent reveals hold any major surprises. Soon, the blonde-in-peril scenario takes over just as predictably as expected, as Elissa is exposed to Ryan’s creepy secrets, although it’s presented with none of the savvy technical flourishes Hitchcock or even Brian De Palma would have employed.

Tonderai’s presentation is hindered by flashing jump cuts, muddy lighting, low angles, occasional handheld shots, and Dutch angles courtesy of cinematographer Miroslaw Baszak. None of these tricks enhance the suspense; rather, they demonstrate how Tonderai is just grasping at straws, trying anything he can to give this tired material some style. Instead, his attempts come off desperate and inconsistent. Consider the movie’s only use of slow-motion during a wild drunken high-school party that’s supposed to be a fund-raising extracurricular. Tonderai shoots teen “hotties” at half-speed, downing beer out of plastic cups, reverses the footage momentarily, and then speeds it up again. This effect and the others mentioned are like a bad music video or commercial helmer was given the reins. And though Tonderai’s experience isn’t vast, all his previous output was for television or direct-to-video releases, which should tell you something.

The movie’s acting is better than one might expect from such a poorly assembled shocker. Thieriot is effective as a soft-spoken weirdo, though he has little fun with mental malfunction once the terror starts up. Shue, former heartthrob in every 1980s movie from The Karate Kid to Adventures in Babysitting, plays a “former rebel trying this mom thing” well. Lawrence doesn’t make a believable teen radical, but her screen presence is enough to get out of not looking her part. Also, Tonderai’s insistence that her character only wears low-cut tank tops becomes suspect after a while. But the proceedings are so incredibly dull that by the time the police officer’s flashlight battery starts acting up during the third act, we’ve stopped caring completely. Rated PG-13, House at the End of the Street was made for fast returns from a teen crowd, and it will certainly make its very low $7 million budget back on opening weekend. It was designed without much thought for this purpose alone, allowing its moviegoing audience to instantly forget this disposable experience the moment the credits begin to roll.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review