The Witch

By Brian Eggert |

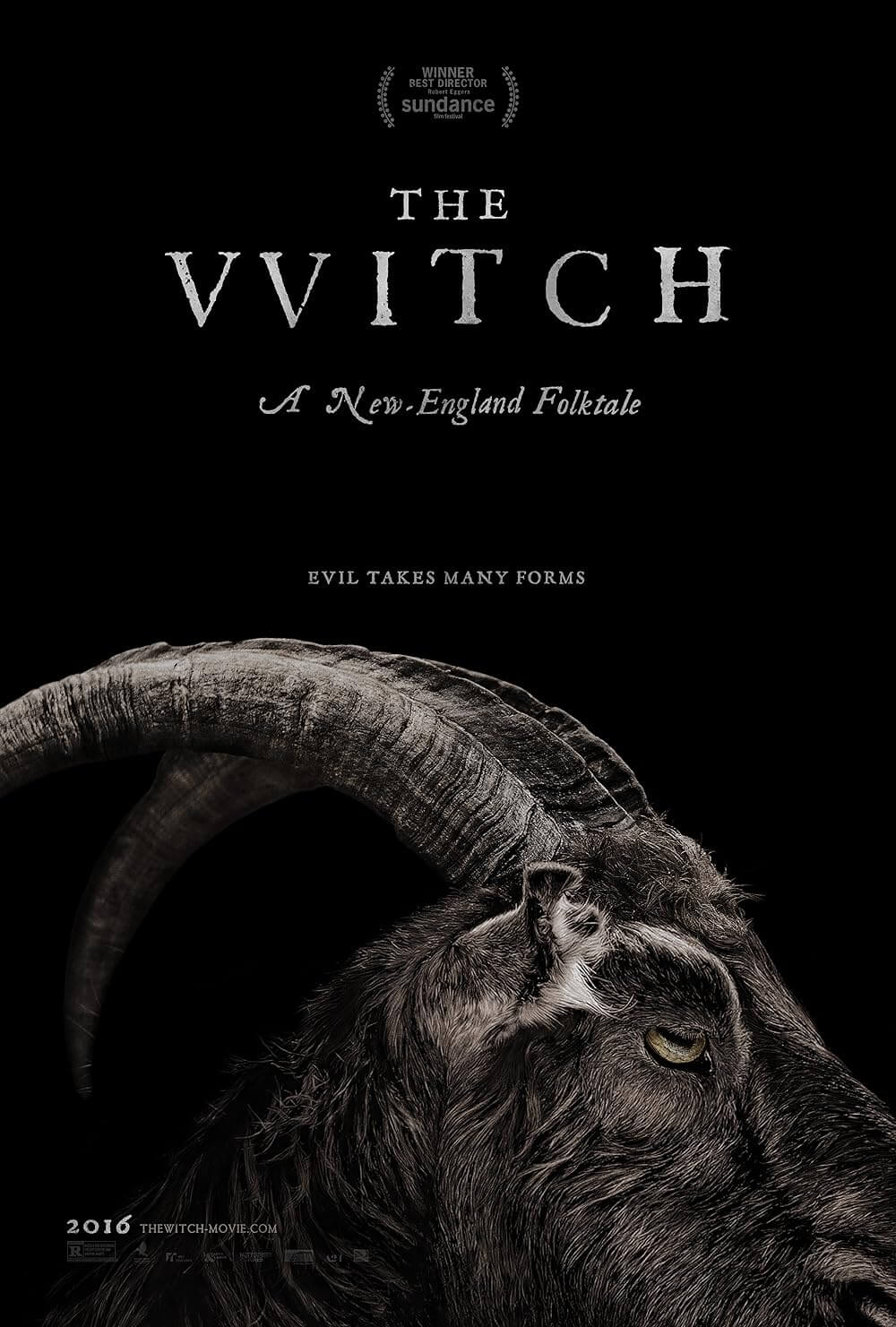

Religious hysteria and frighteningly atmospheric period detail saturate the filmmaking of The Witch, writer-director Robert Eggers’ remarkable debut. A spare and haunting “New England Folk Tale”, the film explores an isolated family torn asunder by the perceived presence of a witch. Though one could argue the film’s pagan threats as real or perceived, its equally haunting, evocative, unsettling imagery and a masterful control of tone creep under the viewer’s skin. Eggers straddles the line between realist doubt and supernatural horror for much of the film, and regardless how you feel about the spiritual concept of witchcraft, the viewer is slammed with unbelievably scary images and concepts. Far removed from today’s slapdash supernatural horror yarns, a market seemingly cornered by Blumhouse Productions (Paranormal Activity, Sinister), The Witch is a picture with equal measures of artistic integrity and genuine terror.

Set on the edge of a New England forest around 1630, about fifty years before the notorious Salem witch trials, the film adopts meticulous detail and seems to hail from that period. The setting is impressively assembled, ornamented with subtle and careful researched facets that immerse the viewer in the period. A post-film message tells us most of the dialogue was taken from actual journals or accounts of the era’s suspected witches, while production designer Craig Lathrop, art director Andrea Kristof, and set decorator Mary Kirkland achieve a superior class of verisimilitude. Shot in earthy and grayed-out tones by cinematographer Jarin Blaschke, the film resembles an old photograph, whereas more witchy scenes bring to mind Danish filmmaker Benjamin Christensen’s 1929 pseudo-documentary Häxan, about the history of witchcraft and Satanism.

Isolated in the wilds of untamed land (shot in Ontario’s woodlands), farmer William (Ralph Ineson) brings his religiously stern wife Katherine (Kate Dickie) and their five children to the middle of nowhere to make a home for themselves. Early on, their suggestively named teenage girl Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) plays with their infant son Samuel, who somehow goes missing into the woods during a game of peek-a-boo. His fate seems to reside in an abhorrent blood rite carried out by a naked elderly woman, although perhaps what we’re seeing is Katherine’s worst fears. Either way, Thomasin is blamed by her mother, while William tries to protect his daughter from his wife’s accusations and derision. Meanwhile, Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), the second eldest, goes missing in the forest while searching for pelts and food. It’s almost a non-issue for the rambunctious twin siblings, Mercy (Ellie Grainger) and Jonas (Lucas Dawson), who don’t seem too affected by the ordeal—they’re more concerned with Black Phillip, the family’s large, eerily named goat.

Religious paranoia shapes how the family responds to these occurrences in countless ways. William’s initial spat with his village’s council results from some manner of disagreement over religious beliefs, which led to his family making a home in the woods in the first place. And after Samuel is taken, his parents believe the infant is damned to Hell because he had not yet been baptized. When the family’s series of white lies regarding a missing silver cup or the true intent of an apple gathering expedition are exposed, these lies are perceived by Katherine as the devil’s work. To be sure, all of them are subject to the draw of lies and impure thoughts, regardless of their devout routines. In an early scene, Caleb spies his elder sister’s growing bosom in hidden glances, suggesting the adolescent has recently begun exploring notions of sexuality, albeit incestuously. Stranger still is the moment Caleb, seemingly possessed, speaks in tongues of a rapturous relationship with Christ—deriving from the ever-odd Christian metaphor that bonds the Christian to Christ through a sort of matrimony, with sexual allusions abound.

Religious paranoia shapes how the family responds to these occurrences in countless ways. William’s initial spat with his village’s council results from some manner of disagreement over religious beliefs, which led to his family making a home in the woods in the first place. And after Samuel is taken, his parents believe the infant is damned to Hell because he had not yet been baptized. When the family’s series of white lies regarding a missing silver cup or the true intent of an apple gathering expedition are exposed, these lies are perceived by Katherine as the devil’s work. To be sure, all of them are subject to the draw of lies and impure thoughts, regardless of their devout routines. In an early scene, Caleb spies his elder sister’s growing bosom in hidden glances, suggesting the adolescent has recently begun exploring notions of sexuality, albeit incestuously. Stranger still is the moment Caleb, seemingly possessed, speaks in tongues of a rapturous relationship with Christ—deriving from the ever-odd Christian metaphor that bonds the Christian to Christ through a sort of matrimony, with sexual allusions abound.

The Witch oozes with symbols of evil and demonstrates how religion feeds off those symbols; however, this story at once exposes and reinforces the witchcraft lore of the period. Eggers plants several seeds of doubt, suggesting the whole picture could be a result of a psychological breakdown from starvation, fear, and suspicion. The whole thing alludes to the frantic terror that propelled the Salem witch trials years later. But just as the viewer can dismiss many of the events in the film as paranoia, they can also see each event as another building block arranged by a supernatural force. Certainly, Eggers’ approach demands comparisons to Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, where the fear of cabin fever becomes realized in the most horrifying ways. Kubrick’s influence can be found everywhere from the long-held shots to scorer Mark Korven’s music of dissonant strings and choral moans, which recall the ghostly sounds coming from the empty hallways of The Overlook Hotel.

With excellent performances from the entire cast (in particular the younger performers), The Witch effectively sets the viewer down in a time and place and creates a lasting sense of unease for its rather brief running time of 92 minutes. If there’s a false moment in the whole picture, it’s near the end when some conspicuous CGI floating spoils the otherwise perfectly assembled period mise-en-scène. But no matter, the bulk of Eggers’ film contains a formal integrity rarely seen in today’s horror films. The Witch‘s quiet intensity early on gives way to an emergent feeling of dread that pulls the viewer along, mouth often agape at the troubling tone and spare approach of the experience. And when the film shows us a moment of witchcraft, real or fantasy, the images are frightening and uniquely composed so as to burn their memory on our brains. In the end, Eggers has made an unforgettable film that leaves us eagerly anticipating what he’ll do next.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review