Heist

By Brian Eggert |

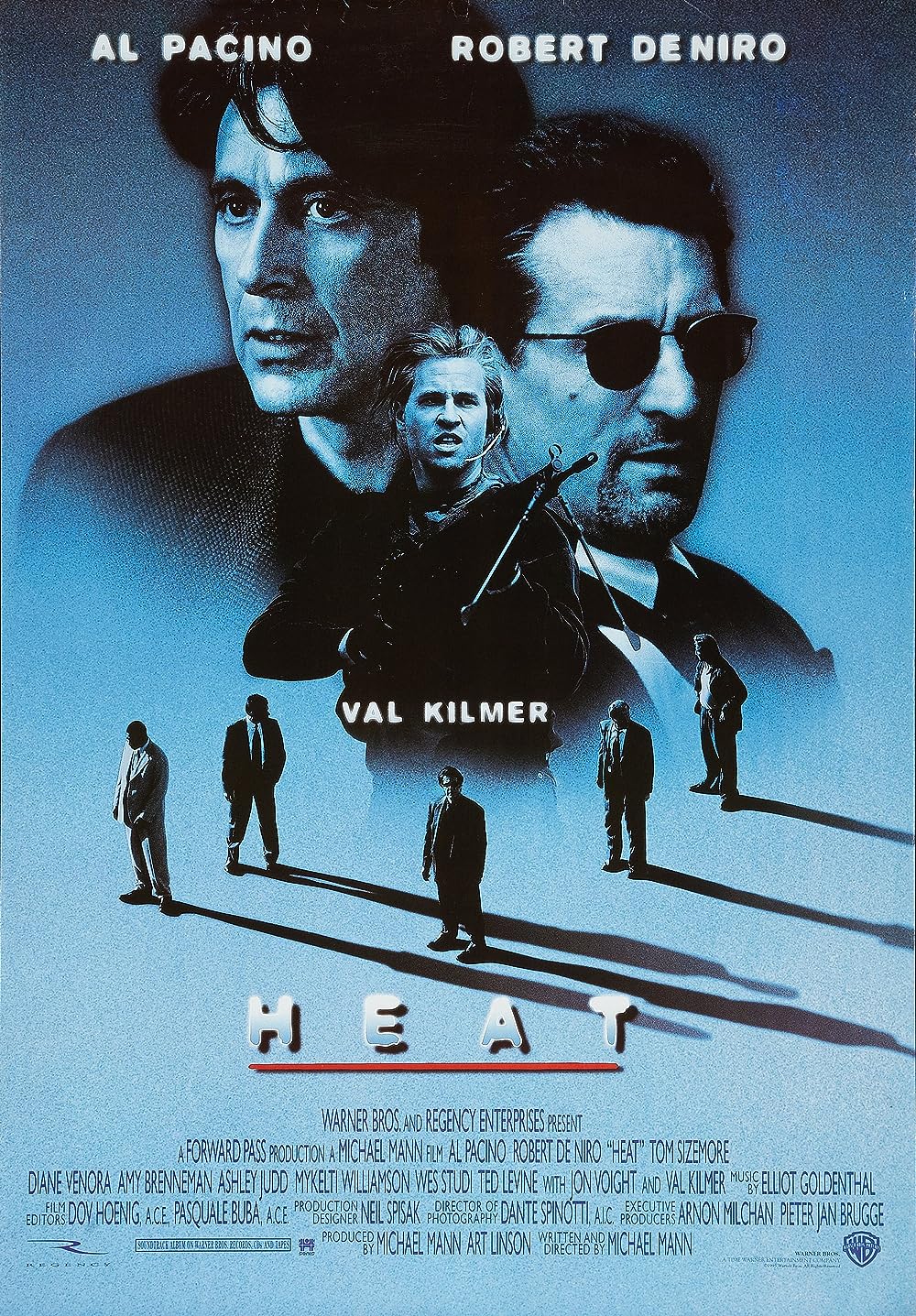

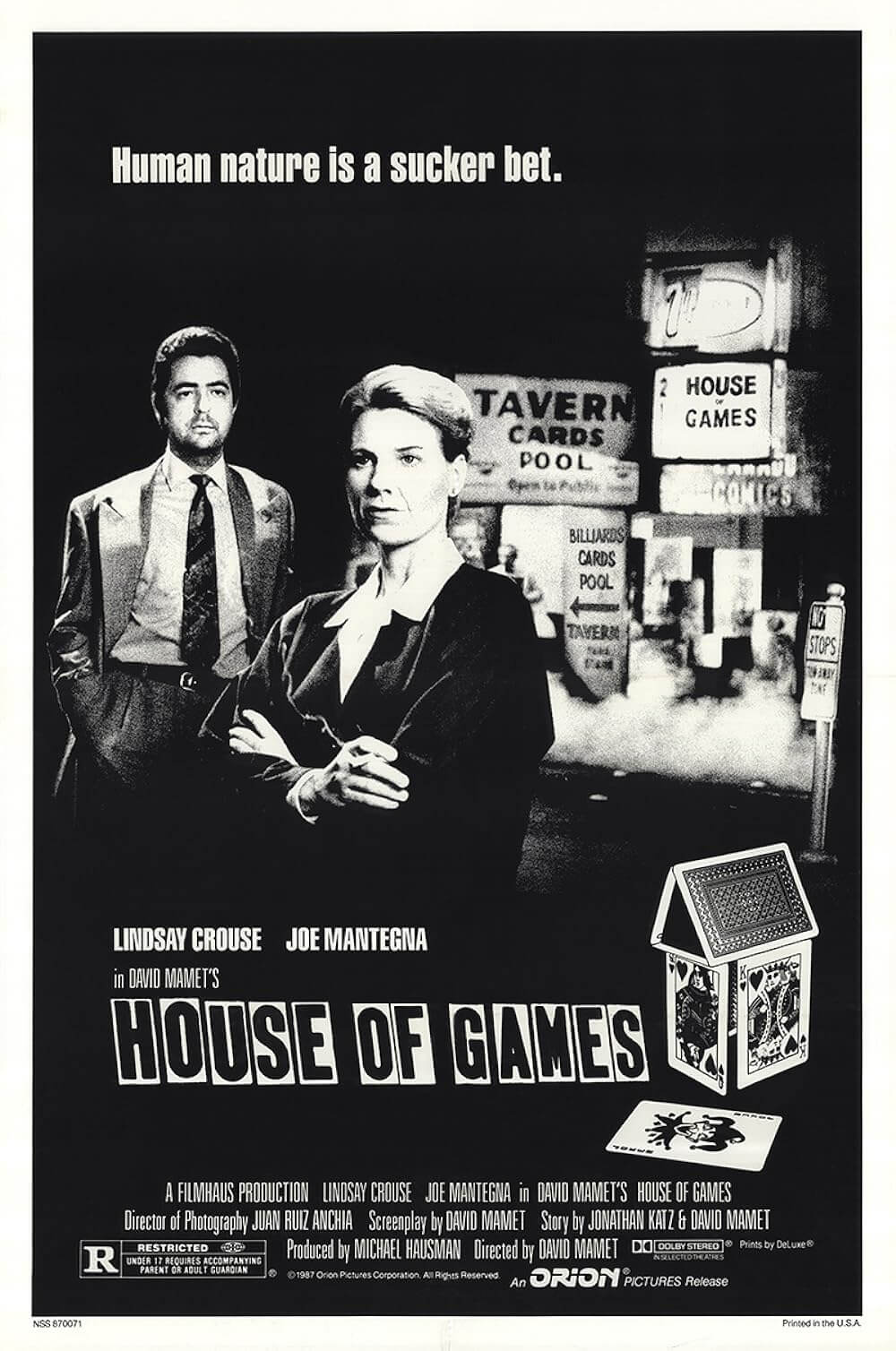

David Mamet embraces a classical and, as some have argued, commonplace subgenre in Heist, a twisting caper about a professional thief carrying out the proverbial “one last job”. Hollywood has explored these plot blueprints in countless films ranging from the probing masterworks of Michael Mann (Thief, Heat) to the rompish entertainment value of Steven Soderbergh’s Oceans trilogy. Today the formula has all but lost its potency, though Heist remains an exception as both complex and decidedly fun storytelling. In his 2001 film, Mamet underscores the subgenre’s appeal but by reinventing it, as the writer-director often does; for example, he deepened the cop drama in Homicide (1991) and reformatted the martial arts competition movie in Redbelt (2008). Rather, with a cast of unrivaled powerhouse actors at his disposal, Mamet remains true to prototypical “heist movie” outlines, delivering a cleverly constructed and wonderfully acted yarn in which his brand of acerbic, dialogue-driven scenes reinforce why these stories are told again and again.

Although his films are generally well received, Heist met with critical resistance for Mamet’s outward devotion to the otherwise commonplace “one last job” setup. Some critics refused to see beyond Mamet’s choice of material, focusing on his story mechanics over the subtlety of his characters or the sheer pleasure of his dialogue. Several critics complained that his approach lacked technical finesse. Variety critic David Rooney argued, “The gold heist itself and some late-reel gunplay could have benefited enormously from more stylish handling.” Rooney seems to have expected an Alfred Hitchcock or Brian De Palma picture and must’ve forgotten Mamet’s films are more about dialogue and intricate characters than elaborate camerawork. Steven Rosen at The Denver Post called the film “generic,” and Mike Clark in USA Today deemed it “mellow cable material.” Even those who praised the film did so mildly, with remarks like “not memorable Mamet” and “a whiff of disappointment” staining otherwise positive reviews. A rare few recognized what Mamet was going for was not something entirely new, but instead an homage to classic crime tales.

Our first indication of this comes before the opening credits with the black-and-white Warner Bros. logo, done up to recall the silvery logo of Golden Age gangster movies and film noirs. From here, we meet Mamet’s cast of characters, a deceptively simple lot of tropes headed by Joe Moore (Gene Hackman), a career thief. Joe’s crew consists of his most trusted partner Bobby Blane (Delroy Lindo), the lesser Pinky Pincus (Ricky Jay), and Joe’s wife Fran (Rebecca Pigeon), an evident femme fatale. After a slickly conceived jewel heist goes wrong in the first sequence, resulting in Joe’s face on a security camera tape, Joe’s crew is pressured into carrying out their next job, as it’s already been “financialized” by their crooked fence, Mickey Bergman (Danny DeVito, in a role that would’ve been played by anyone from Edward G. Robinson to Peter Lorre to Humphrey Bogart). Everyone except Bobby seems to think Joe is slipping, and to ensure Joe doesn’t skip town to evade the heat in early retirement, Bergman assigns his lackey Jimmy Silk (Sam Rockwell) to the crew for their next job, which involves lifting Swiss gold bars from an airport tarmac.

With names like Pinky, Mickey, and Jimmy Silk, Mamet’s film carries an air of noirish classicism, as if we’ve been transported into the seedy worlds of John Huston’s Asphalt Jungle (1950) and Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956). Accordingly, many of Heist’s pleasures come from watching Joe and company plan the henceforth named “Swiss job” on their respective clipboards, rigging explosives and talking about rental vans and so forth, none of which we understand until the actual heist unfolds before us. Joe insists on backup plans upon backup plans, inciting Jimmy Silk to ask why something should go wrong with the supposed perfectly conceived plan. Joe responds coolly, “Y’ever cheat on a woman? …When you called her up, d’you have an excuse? …What if she didn’t ask? …What was your alibi, a waste of time?” But no backup plan is a waste of time in Heist, as the double-crosses keep coming in the film’s second half. Jimmy Silk, inevitably, backstabs Joe for the gold, and Fran, who, sent by Joe on a Mata Hari mission for information, falls for her mark in the process.

With names like Pinky, Mickey, and Jimmy Silk, Mamet’s film carries an air of noirish classicism, as if we’ve been transported into the seedy worlds of John Huston’s Asphalt Jungle (1950) and Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956). Accordingly, many of Heist’s pleasures come from watching Joe and company plan the henceforth named “Swiss job” on their respective clipboards, rigging explosives and talking about rental vans and so forth, none of which we understand until the actual heist unfolds before us. Joe insists on backup plans upon backup plans, inciting Jimmy Silk to ask why something should go wrong with the supposed perfectly conceived plan. Joe responds coolly, “Y’ever cheat on a woman? …When you called her up, d’you have an excuse? …What if she didn’t ask? …What was your alibi, a waste of time?” But no backup plan is a waste of time in Heist, as the double-crosses keep coming in the film’s second half. Jimmy Silk, inevitably, backstabs Joe for the gold, and Fran, who, sent by Joe on a Mata Hari mission for information, falls for her mark in the process.

The action leads to a concluding dockside shootout of incredible simplicity and intentional minimalism. Joe, who seems to have resisted guns throughout his career, squares off against Mickey and his goons. Once gunfire erupts, cinematographer Robert Elswit keeps his distance and limits camera movements. Elswit—an Oscar winner whose sometimes flashy lensing has enhanced the films of P.T. Anderson and elaborate heist movies like The Town and Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol—restrains himself under Mamet’s direction, which always approaches characters and scenes with the blunt truth of the situation. These are not skilled gunfighters; rather, as Roger Ebert pointed out, “this is arguably the first gunfight of their lives.” Watch Mickey as he’s taken aback by the shooting; he barks ”Let’s talk this over!” to everyone there. But talk has played itself out. Joe has had enough. Mickey, bloodied and facing a shotgun barrel, asks, “Don’t you want to hear my last words?” Joe’s response is as unemotional as his reaction to his wife abandoning him. “I just did,” he says, and then pulls the trigger.

It’s possible to watch Heist and ignore all else but the intricacy and flavor of the dialogue. Consider the running allusion to their score as “cute”. For instance, someone says “Cute plan” and Pinky responds, “Cute as a pail full of kittens,” or Joe replies, “Cute as a Chinese baby.” Joe’s crew uses even more colorful imagery to describe their leader; at one point, Pinky says, “My motherfucker’s so cool, when he goes to sleep, sheep count him.” To be sure, Joe earns his reputation by speaking simply, plainly, modestly. When asked how he conceived an ingenious idea, Joe’s response is: “I tried to imagine a fella smarter than myself. Then I tried to think, ‘What would he do?’” The villains’ dialogue is just as juicy: Jimmy Silk promises to be “as quiet as an ant pissing on cotton” and Mickey, in Heist’s most memorable line, shouts, “Everybody needs money. That’s why they call it money!” The characters speak to one another in a kind of shorthand, and the viewer imagines if any covert police operation had a wire in the room, they would be listening to conversations so well guarded by Joe’s crew that deciphering any meaning from them would be impossible. Exchanges about “the thing” and “the job” and “the deal” avoid citing specifics and use a minimum of words in an almost inconceivable number of ways.

None of this dialogue would have been believable had Mamet not cast such incredible actors to perform them. Hackman, 71 at the time, looks more than ten years younger and brings an absolute authority to his role, rendering Mamet’s rhythmic, staccato, pointedly unnatural dialogue in a wonderfully natural way. And while Hackman commands the screen with his presence—built up from dozens of cop, crook, P.I., and military roles over the years—performers like DeVito and Rockwell ornament him well. DeVito is both menacing and hilarious as Mickey, the actor’s small stature and spoken veracity as a dangerous crime boss make for an interesting juxtaposition. Rockwell always excels at playing seedy characters, but rarely has he uttered such pulpy dialogue (“Your guy went out, got his picture on a postage stamp. He got old.”). Most significant though, are the quieter moments of “honor among thieves” between Hackman and Lindo, where the actors, unable to speak emotionally by design, must communicate that their characters understand, respect, and remain loyal to one another in a way that transcends what Mamet has written. After their scenes together at the end, Hackman and Lindo transform Heist into a showcase about professionals who take great pride in a job well done.

None of this dialogue would have been believable had Mamet not cast such incredible actors to perform them. Hackman, 71 at the time, looks more than ten years younger and brings an absolute authority to his role, rendering Mamet’s rhythmic, staccato, pointedly unnatural dialogue in a wonderfully natural way. And while Hackman commands the screen with his presence—built up from dozens of cop, crook, P.I., and military roles over the years—performers like DeVito and Rockwell ornament him well. DeVito is both menacing and hilarious as Mickey, the actor’s small stature and spoken veracity as a dangerous crime boss make for an interesting juxtaposition. Rockwell always excels at playing seedy characters, but rarely has he uttered such pulpy dialogue (“Your guy went out, got his picture on a postage stamp. He got old.”). Most significant though, are the quieter moments of “honor among thieves” between Hackman and Lindo, where the actors, unable to speak emotionally by design, must communicate that their characters understand, respect, and remain loyal to one another in a way that transcends what Mamet has written. After their scenes together at the end, Hackman and Lindo transform Heist into a showcase about professionals who take great pride in a job well done.

Despite pulpy dialogue worthy of Raymond Chandler and enough twists to keep any viewer guessing, Heist was undervalued upon its release in 2001, a year in which several caper movies debuted (Swordfish, The Score, Bandits, and Ocean’s 11), and each contained the same elements, just in a different configuration. But Mamet’s film is more than psychological fake-outs and a maze-of-a-plot, more than heist movie clichés and unpredictable turns stretched to a wonderful degree of implausibility, more than just a cast of familiar and notable faces. The writer-director uses his ensemble to inform his characters, and his dialogue to give his actors depth and personality; he restrains the action to maintain focus on the situation, instead of violence; and he avoids technical flashiness, because this would distract from the film’s exceedingly clever mischief, incendiary wordplay, and otherwise simple pleasures therein. Heist is all of these things, while also embracing the traditions of its subgenre in film. When so few heist movies occupy but cannot overcome the subgenre’s blueprint, Mamet’s Heist remains as singular as its title.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review