White God

By Brian Eggert |

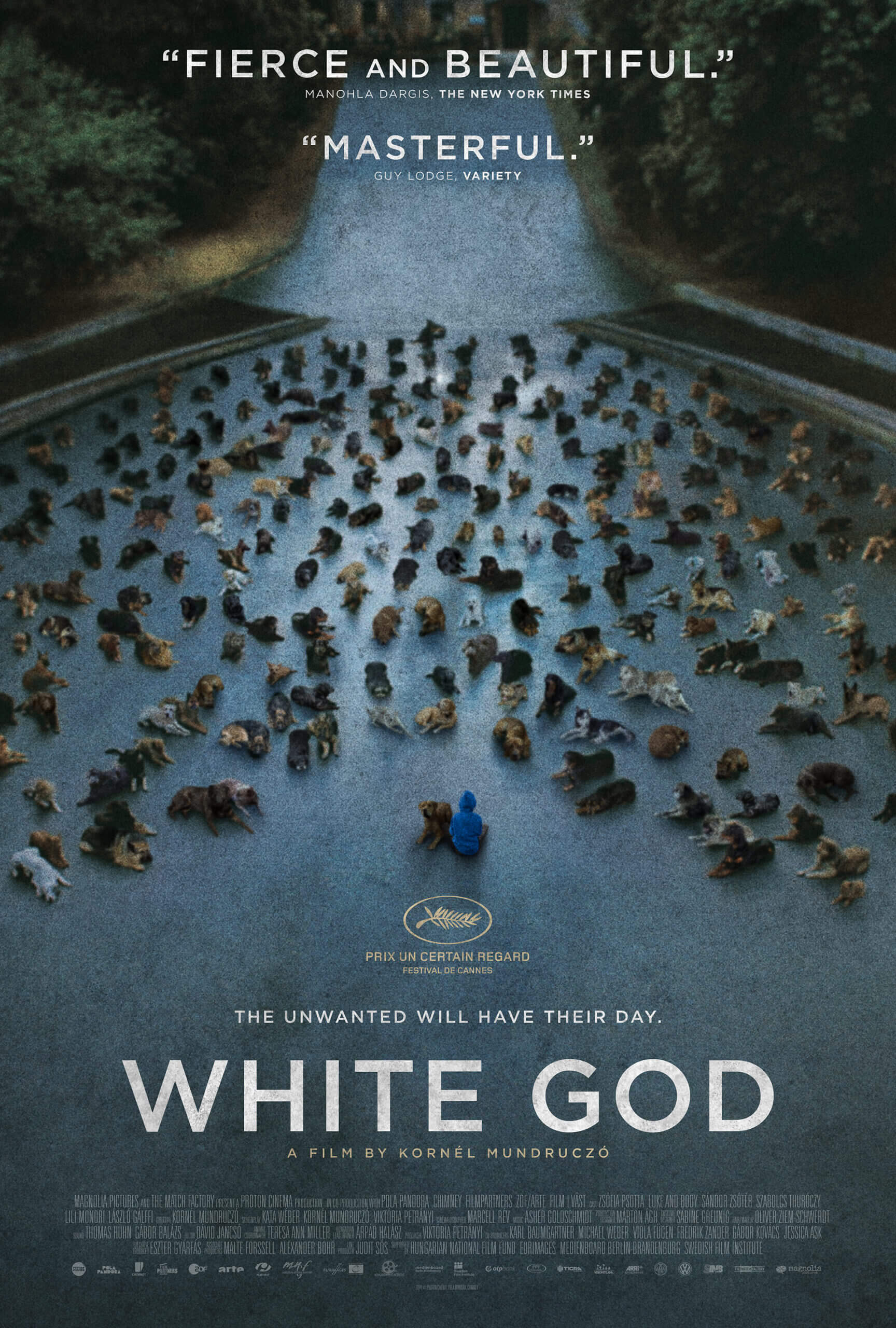

Recent events in the media involving Cecil the Lion reinforce how the horrors suffered by animals at the hands of human beings remain astounding, disgusting, and heartbreaking. White God, a whimsical fairy tale or horror-thriller depending on your feelings about animal rights, is a Hungarian film that puts the audience into the perspective of a dog. Writer-director Kornél Mundruczó creates a dramatic arc around his canine hero, Hagen, a brown, gentle-eyed animal whose journey throughout this devastating experience evokes everything from Amistad to Cujo, as well as several other influences. Inspired after reading South African writer J.M. Coetzee’s 1999 novella The Lives of Animals, Mundruczó began to investigate how dogs were treated in his home of Budapest and found the results appalling. Canine pedigrees represent a class system for many Hungarian owners and pet institutions, wherein purebred animals are treated better and with care, but mixed breed “mutts” are tossed aside and quickly targeted for capture and termination.

Hagen is one such mutt. But the story begins with Hagen’s companion, thirteen-year-old Lili (Zsófia Psotta). When her mother goes on a three-month trip, Lili and her pooch Hagen must move in with her begrudging father, Daniel (Sándor Zsótér), who has no love for dogs. Once Daniel’s neighbors spot Hagen in his apartment, they report him, and now Daniel will be forced to pay a “mongrel” fine. (Hungarian law despises mixed breeds so much that they place a tax on them; however, no tax exists for purebreds.) Daniel would rather get rid of the dog, no matter how Lili feels about it. Lili’s disdain for her father over the situation causes her to bring Hagen to her orchestra practice, where she’s kicked out of class for hiding the dog. She resolves to run away, but her father finds her and abandons Hagen as they drive off. These early scenes are shot like Italian Neorealism, with handheld cameras and on city streets, with an earthy color palette achieved by cinematographer Marcell Rév, bringing a stark sense of reality to what comes next.

Without changing the photography style, the tone and content of White God takes a staggering shift and follows Hagen closely as he interacts with other strays in Budapest. He’s wrangled by a homeless man and sold to a dogfight broker. The broker sells Hagen to a dogfighter, who trains Hagen to attack and how to be angry. And just after his first winning bout, Hagen escapes. Soon, he’s captured by a shelter and, after being identified as a mutt, scheduled for execution. Here White God takes an incredible shift when the beleaguered canine hero rebels, leading a pack of shelter strays on a bloody mission of vengeance. This moment could be interpreted as a mad dog moment, as if Hagen’s dogfight training had been unleashed (pun intended). But once free, Hagen and his small army of dogs target specific people. They stop at the homeless man who sold Hagen, the broker who bought him, his dogfight trainer, and so on. Meanwhile, Lili feels an absence without Hagen and falls low into a reckless lifestyle, but not low enough that she can’t reconcile with her father just in time to search for Hagen when his rebellion starts.

Justifiably, some critics have compared Mundruczó’s film to Rise of the Planet of the Apes, where Hagen serves as Caesar, the smarter-than-average leader of an animal rebellion. But the impetus behind Hagen’s rebellion feels deeply personal, whereas Caesar defended his kind as the smartest of them. The revolt of White God proves more powerful because the dogs haven’t been genetically altered by some brain-improving gas; they simply become fed up with human beings and the horrible ways in which they treat animals. They disregard their own gods, or masters (i.e. humans), and rise up against them. After all, white humans have enslaved countless races through the course of history, declaring them inferior or less-than-human. Some humans treat their dogs, which have an intelligence of a 2 or 3-year-old human child, as if they have no souls (others treat them like their own children, but no matter). In the sense that race and power between humans and dogs play into White God, it’s impossible to watch Mundruczó’s film and not think of Samuel Fuller’s White Dog from 1982—about a black animal trainer who attempts to teach the racism out of an animal trained to kill black people—especially when Hagen and his pack begin attacking.

Justifiably, some critics have compared Mundruczó’s film to Rise of the Planet of the Apes, where Hagen serves as Caesar, the smarter-than-average leader of an animal rebellion. But the impetus behind Hagen’s rebellion feels deeply personal, whereas Caesar defended his kind as the smartest of them. The revolt of White God proves more powerful because the dogs haven’t been genetically altered by some brain-improving gas; they simply become fed up with human beings and the horrible ways in which they treat animals. They disregard their own gods, or masters (i.e. humans), and rise up against them. After all, white humans have enslaved countless races through the course of history, declaring them inferior or less-than-human. Some humans treat their dogs, which have an intelligence of a 2 or 3-year-old human child, as if they have no souls (others treat them like their own children, but no matter). In the sense that race and power between humans and dogs play into White God, it’s impossible to watch Mundruczó’s film and not think of Samuel Fuller’s White Dog from 1982—about a black animal trainer who attempts to teach the racism out of an animal trained to kill black people—especially when Hagen and his pack begin attacking.

Fortunately, there’s some reassurance that Mundruczó went to great lengths to protect the 250 street dogs used in the film. Titles appear before the film: “All of the untrained dogs who perform in this film were rescued from the streets or shelters and placed in homes with help from an adoption program.” Though this restores some confidence in the production, it’s not what we’re accustomed to seeing: the American Humane Association’s “No animals were harmed during the making of this film”. But the Hollywood Report debunked many of the AHA’s animal-friendly procedures in a 2013 exposé, citing one case of negligence (among many) where the animal trailer on The Life of Pi tries to cover up how close their Bengal Tiger came to drowning on set. Today, most filmmakers use CGI to create animal performances and avoid dealing with often troublesome animal actors, their trainers, and animal rights organizations. But Mundruczó recently told interviewer Noah Gittell, “In the CGI, there is human imagination in it. Not the animal. I’m not brave enough to think I know what is inside of an animal’s soul. Only an animal can show that.” Sadly, two or three scenes show a dog lifted by its neck skin or dragged with a snare, and the image could not have been achieved without some considerable discomfort for the animals.

Still, anyone who’s owned or been around dogs can see the animal trainers and filmmakers have cleverly cut around dog tricks and play, using the thematic context and clever editing to shape the images into, what appears to be violent encounters. When Hagen enters a dogfighting ring with a fearsome opponent, the fight looks brutal and bloody. It brought tears to my eyes. Watch it closer and you see Hagen’s tail wagging. The trainers had taught the two dogs to play in the ring for weeks. And when you add a little fake blood and edit it cleverly, it looks like a dogfight. Elsewhere, a small dog is shot by a policeman at close range. We see the animal on its back, clearly “playing dead” for the camera, again with some fake blood rubbed in its fur. The film uses these manipulated, harsh images to create an animal consciousness, to put us inside the dogs’ frame of mind. Elsewhere, Mundruczó is not so reserved. Lili’s father Daniel works in a beef processing plant, and the film shows cows being walked to the slaughter, skinned, bisected, and Daniel checking the heart to ensure it’s approved for consumption. He has long disassociated animals from anything but food, which plays into his inability to relate to Lili about her love for Hagen.

Animal treatment aside, the best actors onscreen are canines. Psotta and Zsótér serve their roles well during the heights of their characters’ confrontation, but the dogs remain the standouts, in particular Luke and Body (pronounced “Bodie”), the indistinguishable dogs who played Hagen. Another pooch, a scrappy little white thing that goes uncredited, provides a lively sidekick for our hero. But it’s the fear, anger, and loneliness in Hagen’s expressions that draws the viewer to him. (No wonder that, in addition to the film winning the “Prize Un Certain Regard” at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival, Luke and Body’s canine performances earned the prestigious Palme Dog, an honor also shared by Uggie in The Artist.) Somehow the film’s repeated use of Ferenc Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsodies” articulates every heartfelt dog emotion throughout the picture, right to the very end—as Lili’s trumpet lullaby to Hagen; on television, as Hagen watches a Tom & Jerry favorite where Tom performs Liszt’s heavy notes on the piano; and the piece chosen by Lili’s orchestra.

What does the title White God mean, then, aside from a questionably intentional reference to Fuller’s film? White people have subjugated so-called minorities for centuries, proclaiming their superiority based on skin color, and the humans in this film are entirely white-skinned. Could White God represent a metaphor for those subjugated races who proclaimed their place in history through various civil rights actions? Or does Mundruczó simply mean to address animal rights issues within Budapest through an artful, engrossing film? That both could be true, or even other meanings not considered within this review, remains the film’s lasting impact. Mundruczó has created a haunting, beautiful, and very readable film; it’s evocative for how well it captures the depth of emotion swelling in canines. As mentioned earlier, Cecil the Lion’s fate reinforces an overarching theme in White God: instead of attempting to control and dominate Nature, the more humane thing to do would be for humans to become active participants in Nature’s design, rather than playing the role of deities.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review