Watchmen

By Brian Eggert |

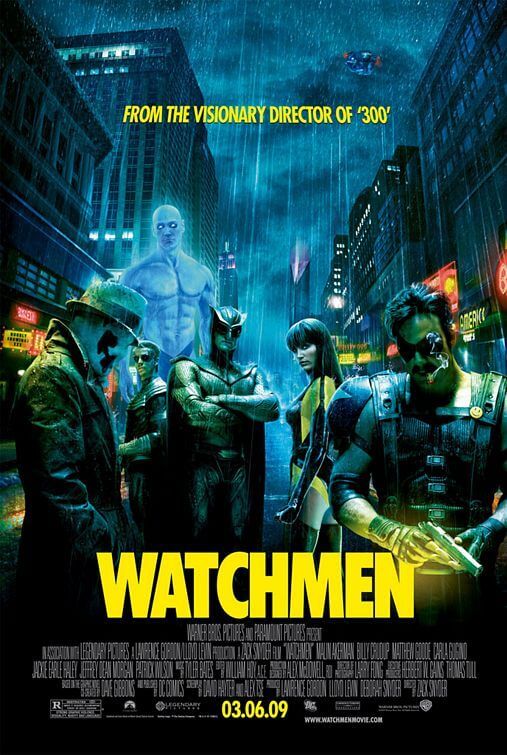

Zack Snyder’s Watchmen will scatter audiences in every direction. Based on the graphic novel by Alan Moore, whose weighty prose earns high praises as serious literature, the film contains enough deviations from and adherences to the source material to split viewers. Not only will film critics and comic aficionados have their separate feelings, as usual, but devotees to Moore’s text are sure to divide even within their own groups. Some will say the film is astonishingly faithful. Some will grumble that it strays from Moore’s intended purpose. And they’d both be right. Moore (the author of V for Vendetta and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen) has already renounced Snyder’s film. But he dismisses all comic-to-film adaptations of his work, refusing ever to watch them, so that’s a moot point. His story begins with the death of a superhero, which should indicate this isn’t your average comic book yarn. The good guys do not prevail, there are no supervillains, and the narrative cares less about the plot and more about the allegorical world that serves as a platform against which we compare our own. Snyder replicates Moore’s structure and environment with impressive skill, but closer examination reveals cracks in this film’s big-budget foundation.

Set in an alternate version of the 1980s, the film finds Richard Nixon serving his third term; nuclear war with Russia imminent; and super-powerless, glorified cops with masks known as superheroes outlawed. The story follows an investigation into the murder of the nihilistic, government-employed hero The Comedian (Jeffrey Dean Morgan). Fellow “watchman” Rorschach (Jackie Earle Haley, in an incredible performance), a paranoid vigilante bent on extremes of justice, demands reprisal against whoever killed his comrade. He seeks out other members of his superhero team, most of whom are now retired, to help uncover a scheme more ingrained than any of them can imagine. The characters’ motivations and inner conflicts are informed by detailed backstories, which are told with a flashback-heavy structure and methodical use of exposition.

Rorschach narrates over an atmospheric neo-noir environment: a dark and ominous New York City where it always rains, and his dialogue void of pronouns, his past riddled with tragedy. Though Rorschach’s character arc is the story’s most compelling, we also meet his former teammates. Dan Dreiberg (Patrick Wilson) slowly realizes he was most alive in his Nite Owl II costume. Ozymandias (Matthew Goode), considered “the smartest man in the world,” left his costume and secret identity behind to become a billionaire; he now protects the world through big business. Dr. Manhattan (Billy Crudup) appears like a god, singular and naked in his glowing blue form; he’s the only hero in the film boasting actual powers, as he manipulates matter and travels anywhere with just a thought. Dr. Manhattan’s sweetheart is Silk Spectre II (Malin Akerman), daughter of the time-trodden Silk Spectre I (Carla Gugino). She leaves her luminescent boyfriend for some nocturnal bird action, which, as you might imagine, causes some problems.

In this historically specific yet alternate-reality-based context, Nixon’s America offers arrogant overconfidence just waiting to be taken down a notch. Even today, we Americans think of ourselves as the world’s heroes, gallivanting about the globe to stop this or that conflict. We unwittingly punish our own with every new undertaking, riding a raft of dead bodies from a sinking ship to reach the shore. This creates a decisive purpose for Watchmen’s themes since the plot’s culprit determines that killing their own, and ultimately the innocent, is the best path to progress. Long after the film is over, you’ll be asking yourself if this harsh lesson bears truth.

Along with the humanization of superhero figures, the story invalidates hero ideals by realizing that every action, no matter how heroic, has a potentially negative response. Unless heroes fight equally to protect humanity (nothing like those numerous government-based figures Captain America and Iron Man), a hero risks becoming a bureaucratic tool. Ironically, just as the comic book film has come into its own with gravitas-laden works like Christopher Nolan’s Batman series or Marvel’s burgeoning renaissance in the last year, justifying itself beyond a sub-genre of fluff and moving into artistic entertainment, Watchmen undoes the idea of superheroism. With comic book movies becoming more grounded in reality all the time, this film asks us to look inquisitively at moral and political dilemmas potentially resulting from a hero’s actions. And as they move in this direction, they inch the genre away from your standard hero vs. villain popcorn-munching fun.

Moore’s original graphic novel, long considered an “unfilmable” text, having won awards and accolades galore, provides an unlikely narrative for conversion to film. Despite avoiding the traditional archetypes for superhero movies, the story itself does not scream blockbuster, epic though it may be. Nevertheless, discussions for a Hollywood adaptation have gone on for two decades. The impressive list of once-involved directors includes Terry Gilliam (Brazil), Darren Aronofsky (The Wrestler), and Paul Greengrass (The Bourne Supremacy), whose names each present intriguing hypothetical results. Finally, after Snyder’s popular adaptation of Frank Miller’s 300, Warner Bros. found the appropriate choice to adapt Moore’s story. And the production went smoothly until Fox took Warners Bros. to court over a decade-old rights claim; they earned themselves a piece of Warner’s box office and a hefty settlement as a result.

The rights dispute did not impinge on the final product, however. Snyder continues his bad habit of embracing visual boldness ahead of compositional consistency. He accomplishes this through graphic, bloody violence, impeccably realized cinematography, and top-notch special effects. Luckily, his biased attention toward visuality works in unison with the script by Alex Tse and David Hayter (X-Men). Employing his standard, excessive use of slow-motion and sudden accelerations in film speed, Snyder’s usual bag of tricks finds surprising cohesion within the film. Though extended fight scenes feel forced for the sake of action-hungry moviegoers, who no doubt expect elaborate sparring from a comic book movie, the slow-motion renders these scenes more dramatic. The cool-colored palette of the film makes for tasty eye candy, and the referential hidden details in the background are more than enough to demand a second viewing.

However, Snyder’s choices occasionally deter from the gravity of the narrative and result in an overall tonality that feels inconsistent. Consider the production’s soundtrack, filled with rock ‘n’ roll and pop music from the film’s era—everything from “99 Luftballons” to Jimi Hendrix to Bob Dylan. Some songs fit their scenes completely; others seem like an unnecessary wink at the audience in an already involving satire. Music is such a crucial connecting device in any film, but with his Dawn of the Dead remake and even 300, Snyder’s penchant for rockin’ music has cheapened each film donning his name. If only an orchestrated score had accompanied Watchmen throughout, it could have been elevated to something more significant on the plane of The Dark Knight.

Comic book aficionados will balk at the changed ending. But, without spoiling what happens, the ending’s result is ultimately the same as the graphic novel, except altered in its specificity. The guts have been ripped out of it. In what should have been a head-on collision with the audience, Snyder, or the influence of studio execs, made sure to pad the blow, leaving the viewer with a feeling of optimism. Dismal and lost, ruined and ashamed of humanity—this is how the audience should walk away from Watchmen. It’s certainly how readers feel after finishing the graphic novel, not thinking everything will be okay. Likely, Hollywood needed Snyder to provide reassurance, and by following that directive, he sacrificed the intensity of the finale.

Snyder captures the graphic novel’s characters and the majority of events in all their multifaceted glory, enough even to garner criticism for his unreal, comic book-like characterizations and distant pitch. Part of a successful adaptation requires consideration of the medium to make the translation effortless. Snyder doesn’t accomplish this entirely. He tries to ease this process, adding his own signature by incorporating an occasionally awkward pop song, techno-laden fight scenes, and a finale whose potency is diluted. The result disappoints, though not enough to dismiss the picture altogether. There’s mild brilliance here. And it’s certainly worth your time, even with a running time reaching nearly three hours. But because of a few missteps, the film isn’t the grand masterpiece it should be. Ambitious films like this are generally either glorious artistic successes or utter failures; Watchmen uniquely falls somewhere in the middle.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review