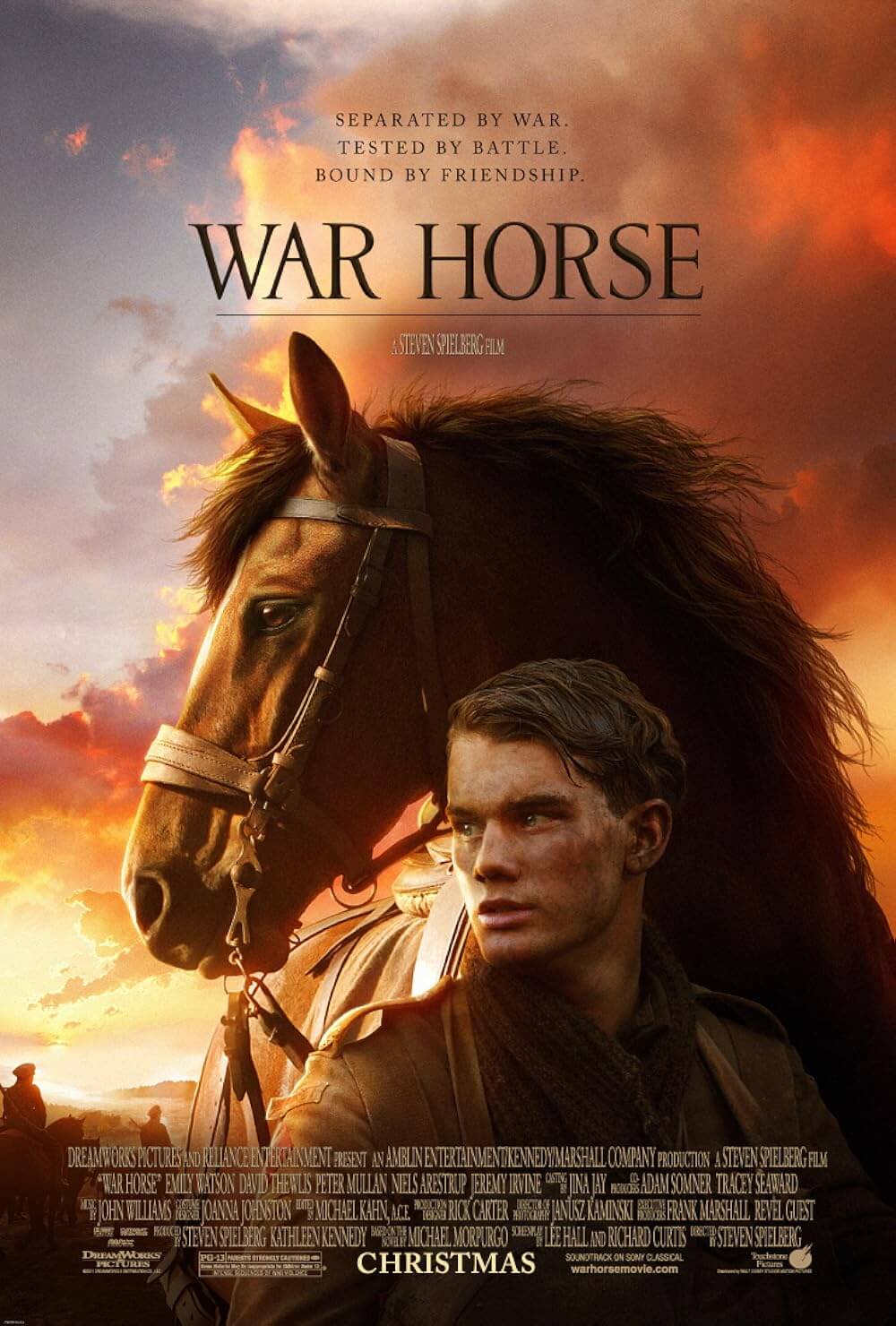

War Horse

By Brian Eggert |

In 1958, to earn his Boy Scout merit badge in photography, at the age of 11, Steven Spielberg completed his first short film, called The Last Gunfight. Shot with his father’s 8mm camera, Spielberg completed the 9-minute Western by filming dusty, mountainous scenery to evoke Monument Valley’s presence in the films of John Ford (My Darling Clementine, The Searchers), personal favorites of the young filmmaker-to-be. Years later, in 1989, after he had become a household name and blockbuster engineer, Spielberg’s opening shot of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade was actually filmed in Monument Valley as an evocation of Ford’s Westerns. It was the Second Unit’s Frank Marshall who completed the shot, however, as Spielberg refused to enter the “hallowed ground” of Ford’s cinema himself out of superstition. Over the years, Spielberg has drawn from Ford to establish his own classicism in his films, which today rival Ford’s in their pathos and scope.

Spielberg returns to Fordian archetypes for War Horse, an epic that sets out from a picturesque farm for a fateful ride across Europe during World War I, only to return in a sweeping “there and back again” journey. Based on the 1982 young-adult novel by Michael Morpurgo, the film follows a theatrical interpretation, which debuted on Broadway, and in 2007 won several Tony Awards, including Best Play. On stage, the production featured a decidedly cinematic treatment, complete with slow-motion battle sequences, while through puppetry, actors portrayed the central character, a horse from whose perspective the story is told. Spielberg’s film, adapted by Lee Hall and Richard Curtis, remains closer to the book, although the play’s more recent popularity no doubt inspired the director and his longtime producer, Kathleen Kennedy, to pursue the project. In an effort to combine his sentimental temperament with his most humanized depiction of war yet, Spielberg delivers an instant classic, and one of 2011’s very best films.

The story opens in the quaint farming village of Devon on the English countryside, where the Narracott family struggles to maintain their farm. Hard-headed paterfamilias Ted (Peter Mullen) heads into town in spring to bid on a plow horse but finds himself drawn to a small hunter colt, a beautiful horse but not suited for farming. Nevertheless, out of stubborn pride, he outbids his malicious landlord (David Thewlis) for the animal, yet at a price that may leave him unable to pay rent or cultivate fields. A drunkard and troubled war vet, Ted returns home, the horse in tow, to find his wife, Rosie (Emily Watson), filled with scorn over the reckless purchase. But their son Albert (newcomer Jeremy Irvine), who has watched neighbors raise the horse since its birth, vows to teach the horse the plow. The boy names him Joey, and the two form a unique bond of trust and love. They keep the Narracott farm running, defying all odds and expectations. But when Nature tragically steps in and ruins the farm’s chances, Ted is forced to lease Joey to British Calvary forces when World War I breaks out. As Joey goes off to war, Albert is steadfast in the belief that they will be together again.

The film’s structure is episodic, following Joey in France as fate moves him from owner to owner. He begins with a bright British officer, Captain Nicholls (Tom Hiddleston), whose superior, Major Stewart (Benedict Cumberbatch), owns a black stallion known as Topthorn. Together, Joey and Topthorn are captured by the Germans and become the impetus for two deserters. Later, the horses are another kind of salvation for a young French girl and her caring grandfather, and later still, they are slaves for pulling heavy artillery behind German lines. With each chapter, Spielberg resists dwelling on the specific atrocities of war as he’s done in Schindler’s List, and instead views the whole as chaos. His film remains blind to borders or sides or politics and finds humanism in a range of nationalities through the horse’s uniquely neutral perspective. In a way, the approach best aligns with that of Spielberg’s WWII drama Empire of the Sun, set from the perspective of a child’s eyes. This is most tenderly accented in the scenes in No Man’s Land, where a British and German soldier emerge from their respective bunkers, each waving a white flag to cut Joey free from barbed wire.

With early scenes on the storybook farm, complete with green pastures and a petulant goose who oversees the property, Spielberg evokes Ford’s homegrown innocence in The Quiet Man and the tonal wholesomeness of Golden Age cinema. These scenes may seem overly syrupy, with composer John Williams’ music punctuating our responses. But it’s here that Spielberg establishes Home, a safe and dependable place of family and Technicolor beauty, just as Peter Jackson does for the Shire in the extended opening of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. From these classical roots, the audience goes to war and witnesses modernized anarchy—killing machine tanks, cynical soldiers, and the pitiless omnipresent struggle—realized by battle scenes that rival those in Spielberg’s own Saving Private Ryan. By the finale, rich with an orange, low sunset blazing across the sky, Spielberg echoes Gone with the Wind, cinematically equating Albert and Joey’s return to the Narracott farm to Scarlett’s return to Tara, her beloved plantation. In each warmly realized note, Spielberg appreciates classic storytelling through imagery that awakens our cinematic memory.

But the film is also decidedly Spielbergian. In terms of story, he portrays another in a long line of semi-autobiographical Spielberg families whose all-but-absent father shapes the son. After all, Albert initially takes on Joey to prove their merits and earn his father’s approval. That desire drives Albert, even after the film’s story-propelling betrayal; as Albert enlists, he does so not only to find Joey but to live up to his father’s legacy. From a technical perspective, Spielberg recruits his crew of regulars: the efforts of production designer Rick Carter, editor Michael Kahn, and costume designer Joanna Johnston place the audience in the period setting with clarity and detail. But it’s Janusz Kaminski’s lyrical photography that brings a sense of wonder to the production. From an extreme close-up that reflects in Joey’s massive, expressive eye to extensive master shots that capture the scope of battle, Kaminski’s cinematography, combined with Spielberg’s ingenuity, delivers images both gorgeous and haunting. One such sequence involves the Calvary riding into a line of German guns at the edge of a forest. We see a grand shot of British soldiers armed with swords and charging on horseback. Cut to German machine guns firing, and then another cut to horses racing into the woods without their riders. As always, Spielberg finds creative ways to tell a story and produce a feeling through compelling images.

War Horse achieves what we can call Spielberg Magic—the sense of splendor and emotion fuelling his most universal pictures, which over the years have solidified him as our time’s most successful and most heartwarming filmmaker, and also the most consistently iconic. In full embrace of this notion, the film is powerful and flows naturally, and it’s bound to reach a wide array of viewers, many of who will need tissues to make it through. Though he doesn’t shy away from grim wartime realities, Spielberg instills themes of family that resonate as the setting changes and Joey passes into the next installment of his story. This heightens our involvement, making every sequence more affecting than the last. More impressive is Spielberg’s ability to maintain perfect control over these changing moods, but then finally, he returns us home, where he restores our sense of safety by channeling great works of cinema. Taking us on this journey, Spielberg has created another incredible, striking film, one sure to become an instant classic, like so many others bearing his master’s touch.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review